The Meuse

We all have them: those boxes in storage, detritus left to us by our forebears. Mine were in the attic, and there were lots of them. Most were crumbling cardboard, held together by ancient twine of various types: the thick cotton kind sold for clotheslines wrapped once around and tied with an emphatic square knot; its weaker version, better suited for wrapping a packet of letters, which required multiple passes and the shaggy blond string used for hay bales, ends raveling.

I remember having seen some of the oldest boxes, those from my father’s and mother’s families, when I was a child. They had been stored in cabinets above the piles of rags where the dogs slept in the carport and had accumulated dander and dog hair from decades of flea-plagued boxers and Great Danes. Though decaying with age, there were unmistakable signs of craftsmanship on these boxes, such as the elegant advertisements from the era stamped on the sides, or the delicate painting on the tin case my father used to ship artworks from “Pnom-Pehn” in the 1930s, which gave them a decorous, dignified air.

In our attic, they kept an increasingly disapproving vigil, it seemed to me, over the promiscuous sprawl of stuff that piled up around them as my husband Larry and I and our kids made our own histories: snapshots, of course, by the thousands, but also letters, science fair exhibits, entubed diplomas, the remains of a costume in which Jessie dressed up for Halloween as a blade of grass, snarley-haired dolls, the sawn-apart cast from Virginia’s broken leg when she was six, a box of my hand-drawn house plans, paper dolls with outfits still carefully hooked over their shoulders, report cards, spangly tutus and soiled, hem-dangling pinafores, receipts, a box of broken candy cigarettes, bank statements, exhibition reviews, a trunk of ball gowns and dress-up clothes, tatty Easter baskets still padded with unnaturally green grass, two pairs of Lolita sunglasses, their plastic brittle and faded, and the section of sheetrock cut from the kitchen of our old house on which the heights of the children were penciled each year.

And, of course, there was also in the attic the residue of my own unexamined past: the many variously sized boxes, secured with brittle masking tape, containing letters, journals, childhood drawings, and photographs. These had been left untouched for decades as I ignored Joan Didion’s sage advice to remain on nodding terms, at least, with the people we used to be, lest they show up to settle accounts at some dark 4 a.m. of the soul.

The tape and twine on these boxes, where my family’s past sleeps, might never have been cut nor their complicated secrets revealed if I hadn’t gotten a letter early in July 2008 from Professor John Stauffer, asking me to deliver the Massey Lectures in American Civilization at Harvard. After reading the letter, I cycled through the familiar antics of disbelief: forehead slapping, eye-rolling, exaggerated scrutiny of the envelope for an error . . . but, no. They wanted me, a photographer, to deliver the three scholarly lectures beginning on my sixtieth birthday, three years down the road, in May 2011.

Rushing to my Day-Timer I searched in vain for a conflict. In fact, I searched in vain for a calendar page that far in the future.

No way could I reasonably decline. Years earlier, my brilliant young friend Niall MacKenzie had been given to prefacing his ironically self-inflating forecasts with the line, “Well, Sally, when they ask me to deliver the Massey Lectures . . . .” I had heard this refrain so many times that the Masseys had come to represent for me the pinnacle of intellectual achievement. But I didn’t think of myself as much of an intellectual, and I was certainly no academic. I wasn’t even a writer. And what did I have to write about, even supposing I could?

I had acquired some acclaim and notoriety, as well as the irritating label “controversial,” in the early 1990s with the publication of my third book of photographs, Immediate Family. In it were pictures I had made of my children, Emmett, Jessie, and Virginia, going about their lives, sometimes without clothing, on our farm tucked into the Virginia hills. Out of a conviction that my lens should remain open to the full scope of their childhood, and with willing, creative participation from everyone involved, I photographed their triumphs, confusion, harmony, and isolation, as well the hardships that tend to befall children–bruises, vomit, bloody noses, wet beds–all of it. In a case of cosmically bad timing, the release of Immediate Family coincided with a moral panic about the depiction of children’s bodies and a heated debate about government funding of the arts. (I had received grants from the NEA and the NEH but not for the pictures of my children.) Much confusion, distraction, internal struggle, and, ultimately, fuel for new work emerged from this embattled period.

Would the Massey committee at Harvard expect me to justify my family pictures all these years later? I didn’t mind doing that, but I hoped I could also focus on the work that came afterward, deeply personal explorations of the landscape of the American South, the nature of mortality (and the mortality of nature), intimate depictions of my husband, and the indelible marks that slavery left on the world surrounding me. With trepidation, I called John Stauffer, and his answer only made me more anxious: anything, speak about anything you want.

Oppressed by this indulgence and uncertain how to proceed, I went into a spasm of self- doubt and fear so incapacitating that it was nearly a year before I told Stauffer I’d do it. And then, as often happens to me, the self-doubt that had dammed up so much behind its seemingly impermeable wall allowed the first trickles of hope and optimism to seep out, and through the widening crack possibility flooded forth. Self-doubt, for an artist, can ultimately be a gift, albeit an excruciating one.

I began looking for what I had to say where I usually find it: in what William Carlos Williams called The Local. I wonder if he would think my admittedly extreme interpretation, working at home, seldom leaving the spacious plenty of our farm, too much Local? For Larry, it sometimes is: he once irritatedly clocked five weeks during which I didn’t so much as go to the grocery store. But like a high-strung racehorse who needs extra lead in her saddle-pad, I like a handicap and relish the aesthetic challenge posed by the limitations of the ordinary. Conversely, I get a little panicked when I have before me what the comic-strip character Pogo once referred to as “insurmountable opportunities.” It is easier for me to take ten good pictures in an airplane bathroom than in the gardens at Versailles.

And so I turned to the boxes in my attic, starting with those that bore witness to my own youth. Who and what would I find in them?

My long preoccupation with the treachery of memory has convinced me that I have fewer and more imperfect recollections of childhood than most people. But having asked around over the years, I’m not so sure now that this is the case: perhaps we are all like the poet Eric Ormsby, writing of his childhood home: We watch our past occlude, bleed away, the overflowing gardens erased, their sun-remembered walls crumbling into dust at our fingers’ approach. And, just as Ormsby wrote, we all would cry “at the fierceness of that velocity /if our astonished eyes had time.”

Whatever of my memories hadn’t crumbled into dust must surely by now have been altered by the passage of time. I tend to agree with the theory that if you want to keep a memory pristine, you must not call upon it too often, for each time it is revisited, you alter it irrevocably, remembering not the original impression left by experience, but the last time you recalled it.

With tiny differences creeping in at each cycle, the exercise of our memory does not bring us closer to the past, but draws us farther away.

I had over time learned to meekly accept whatever betrayals memory pulled over on me, allowing my mind to polish its own beautiful lie. In distorting the information it’s supposed to be keeping safe, the brain, to its credit, will often bow to some instinctive aesthetic wisdom, imparting to our life’s events a coherence, logic, and symbolic elegance that’s not present or not so obvious in the improbable, disheveled sloppiness of what we’ve actually been through. Elegance and logic aside, though, in researching and writing this book, I knew that a tarted-up form of reminiscence wouldn’t do, no matter how aesthetically adroit or merciful. I needed the truth, or, as a friend once said, “something close to it.” That something would be memory’s truth, which is to scientific, objective truth as a pearl is to a piece of sand. But it was all I had.

So, before I scissored the ancestral boxes, I opened my own to check my erratic remembrance against the artifacts they held, and in doing so encountered the malignant twin to imperfect memory: the treachery of photography. As far back as 1901 Emile Zola telegraphed the threat of this relatively new medium, remarking that you cannot claim to have really seen something until you have photographed it. What Zola perhaps also knew or intuited was that once photographed, whatever you had “really seen” would never be seen by the eye of memory again. It would forever be cut from the continuum of being, a mere sliver, a slight, translucent paring from the fat life of time; elegiac, one-dimensional, immediately assuming the yellowed character of golden nostalgia: an instantaneous memento mori. Photography would seem to preserve our past and make it invulnerable to the distortions of repeated memorial superimpositions, but I think that is a fallacy: photographs supplant the past and corrupt our memories, and as I held my childhood pictures in my hands, in the tenderness of my “remembering,” I also knew that with each photograph I was forgetting.

I closed my boxes and turned to those of earlier generations. They had come to my attic in sequence — first Larry’s parents and grandparents then my father and mother — and they had not been opened since the deaths that necessitated boxing up a life. In them was all that remained in the world of these people; their entire lives crammed into boxes that would barely hold a twelve-pack.

When an animal, a rabbit, say, beds down in a protecting fencerow, the weight and warmth of his curled body leaves a mirroring mark upon the ground. The grasses often appear to have been woven into a bird-like nest, and perhaps were indeed caught and pulled around by the delicate claws as he turned in a circle before subsiding into rest. This soft bowl in the grasses, this body-formed evidence of hare, has a name, an obsolete but beautiful word: meuse. (Enticingly close to Muse, daughter of Memory, and source of inspiration.) Each of us leaves evidence on the earth that in various ways bears our form, but when I gently press my hand into the rabbit’s downy, rounded meuse it makes me wonder: will all the marks I have left on the world someday be tied up in a box?

Cutting the strings on the first family carton, my mother’s, I wondered what I would find, what layers of unknown family history? Would the wellsprings of my work as an artist–the fascination with family, with the Southern landscape, with death–be in these boxes? What ghosts of long-dead, unknown family members were in them, keeping what secrets?

I will confess that in the interest of narrative I secretly hoped I’d find a payload of Southern Gothic: deceit and scandal, alcoholism, domestic abuse, car crashes, bogeymen, clandestine affairs, dearly loved and disputed family land, abandonments, blowjobs, suicides, hidden addictions, the tragically early death of a beautiful bride, racial complications, vast sums of money made and lost, the return of a prodigal son, and maybe even bloody murder.

If any of this stuff lay hidden in my family history, I had the distinct sense I’d find it in those twine-bound boxes in the attic. And I did: all of it and more.

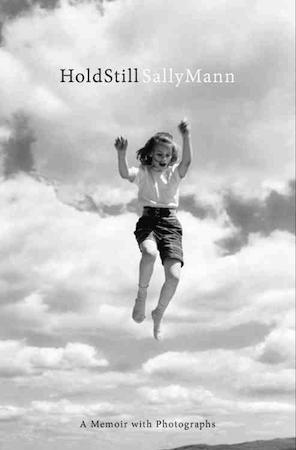

From HOLD STILL. Used with permission of Little, Brown and Company. Copyright © 2015 by Sally Mann.