Here are the first reviews of every Ernest Hemingway novel.

The world breaks everyone and afterward many are strong in the broken places. But those that will not break it kills. It kills the very good and the very gentle and the very brave impartially. If you are none of these you can be sure it will kill you too but there will be no special hurry.

–A Farewell to Arms

On this day in 1899, in Oak Park, Illinois, Ernest Miller Hemingway—the Nobel and Pulitzer Prize-winning, machismo-exuding, globe-trotting war correspondent and troubled titan of 20th Century American fiction—was born.

To mark his 122nd birthday, let’s take a look back at the first reviews of each of Hemingway’s nine published novels, from The Torrents of Spring (1926), to the posthumously released Islands in the Stream (1970) and The Garden of Eden (1986).

Happy Birthday, Papa.

*

The Torrents of Spring (1926)

It was no use now. It was no use trying to capture what had gone. What had fled.

“The delightful entertainment of The Torrents of Spring, if not precisely what might have been expected of the author of In Our Time, is full-blooded comedy, with a sting of satire at the expense of certain literary affectations. The object of Mr. Hemingway’s gravely absurd travesty is somewhat on the side of the advanced intellectual position. The subtle incongruity which he establishes in the character of Scripps and Scripps’s banal introspections is almost too keenly edged. It is, therefore, a somewhat specialized satire. It is almost in the nature of a literary vaudeville, which will appeal mainly to Mr. Hemingway’s fellow-craftsmen. He is not parodying merely a manner but a philosophy and an attitude, a fundamental approach, as well. That calls for a degree of initiation and sophistication in his reader that may not always be available.

The Torrents of Spring reveals Mr. Hemingway’s gift for high-spirited nonsense. Whatever its effect on literary foibles, it contributes to that thoughtful gayety which true wit should inspire. While he ridicules certain extravagances by pushing them to the logical conclusion, Mr. Hemingway obviously entertains a robust respect for the object of his allusive gibes. In the last analysis, the book sets out to amuse. This it does.

–The New York Times, June 13, 1926

The Sun Also Rises (1926)

Everyone behaves badly—given the chance.

“It is a relief to find that The Sun Also Rises maintains the same heightened, intimate tangibility as the shorter narratives and does it in the same kind of weighted, quickening prose. Mr. Hemingway has chosen a segment of life which might easily have become ‘a spectacle with unexplained horrors,’ and disciplined it to a design which gives full value to its Dionysian, all but uncapturable, elements. On the face of it, he has simply gathered, almost at random, a group of American and British expatriates from Paris, conducted them on a fishing expedition, and exhibited them against the background of a wild Spanish fiesta and bull-fight. The characters are concisely indicated. Much of their inherent natures are left to be betrayed by their own speech, by their apparently aimless conversation among themselves. Mr. Hemingway writes a most admirable dialogue. It has the terse vigor of Ring Lardner at his best. It suggests the double meanings of Ford Madox Ford’s records of talk. Mr. Hemingway makes his characters say one thing, convey still another, and when a whole passage of talk has been given, the reader finds himself the richer by a totally unexpected mood, a mood often enough of outrageous familiarity with obscure heartbreaks.

…

The love affair of Jake and the lovely, impulsive Lady Ashley might easily have descended into bathos. It is an erotic attraction which is destined from the start to be frustrated. Mr. Hemingway has such a sure hold on his values that he makes an absorbing, beautifully and tenderly absurd, heartbreaking narrative of it.

…

“No amount of analysis can convey the quality of The Sun Also Rises. It is a truly gripping story, told in a lean, hard, athletic narrative prose that puts more literary English to shame. Mr. Hemingway knows how not only to make words be specific but how to arrange a collection of words which shall betray a great deal more than is to be found in the individual parts. It is magnificent writing, filled with that organic action which gives a compelling picture of character.”

–The New York Times, October 31, 1926

A Farewell to Arms (1929)

The world breaks every one and afterward many are strong at the broken places.

“There is in A Farewell to Arms no change from the narrative method of The Sun Also Rises and Men Without Women. Ernest Hemingway did not invent the method, which is chiefly to be characterized by the staccato nature of sentences (an effort at reproducing universal conversational habit), and its rigid exclusion of all but the most necessary description. Yet if Hemingway was not the inventor of the method, tentative gropings toward such a manner having been made by many of his immediate predecessors, the author of A Farewell to Arms has, in his several books, made it so strikingly his own that it may bear his name, and is likely to henceforward. The method has its advantages, and also its disadvantages.

The chief result is a sort of enamel lustre imparted to the story as a whole, not precisely an iridescence, but a white light, rather, that pales and flashes, but never warms. And because it never warms, or never seems to warm, the really human in Hemingway (and there is a great deal in Hemingway that is human) fails of its due. It is not impossible that Ernest Hemingway has developed his style to the extreme to which he carries it because in it he finds a sort of protective covering for a nature more sensitive than he would have one know.

…

“There will be debate as to whether A Farewell to Arms is a finer piece of work than The Sun Also Rises. And there will be cogent arguments advanced on either side. On the surface, the newer story is more effective than the earlier novel. There is more drama, the movement is more nearly continuous and better sustained. And the story of the love between the English nurse and the American ambulance officer, as hapless as that of Romeo and Juliet, is a high achievement in what might be termed the new romanticism. And yet for the present reviewer The Sun Also Rises touches a note which Hemingway caught once, and, in the very nature of the thing, cannot touch again.”

–Percy Hutchison, The New York Times, September 29, 1929

To Have and Have Not (1937)

Death is like an old whore in a bar—I’ll buy her a drink but I won’t go upstairs with her.

“The indications of such a growth are absent from this book, as they have been absent from everything Mr. Hemingway has written since A Farewell to Arms. There is evidence of no mental growth whatever; there is no better understanding of life, no increase in his power to illuminate it or even to present it. Essentially, this new novel is an empty book.

…

”The expertness of the narrative is such that one wishes profoundly it could have been put to better use. There is cumulative power and telling economy of phrase. There is driving action. And there is also pointless brutality, passages of purely sadistic writing. The famous Hemingway dialogue reveals itself as never before in its true nature. It is false to life, cut to a purely mechanized formula. You cannot separate the speech of one character from another and tell who is speaking. They all talk alike.

In spite of its frequent strength as narrative writing, To Have and Have Not is a novel distinctly inferior to A Farewell to Arms. There is nothing in it comparable to the final chapter of the earlier book, or to the story of the retreat from Caporetto. Mr. Hemingway’s record as a creative writer would be stronger if it had never been published.”

–J. Donald Adams, The New York Times, October 17, 1937

For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940)

The world is a fine place and worth fighting for and I hate very much to leave it.

“All that need be said here about the new Hemingway novel can be said in relatively few words. For Whom the Bell Tolls is a tremendous piece of work. It is the most moving document to date on the Spanish Civil War, and the first major novel of the Second World War.

As a story, it is superb, packed with the matter of picaresque romance: blood, lust, adventure, vulgarity, comedy, tragedy. For Robert Jordan, the young American from Montana, the lust and adventure are quickly drowned in blood. The comedy, as in other Hemingway fiction, is practically indistinguishable from the vulgarity, which in this case is a rich and indigenous peasant brand. The tragedy is present and only too plain; the bell that began tolling in Madrid four years ago is audible everywhere today.

…

“Mr. Hemingway has always been the writer, but he has never been the master that he is in For Whom the Bell Tolls. The dialogue, handled as though in translation from the Spanish, is incomparable. The characters are modeled in high relief. A few of the scenes are perfect, notably the last sequence and an earlier one when Jordan awakes to the sound of a horse thumping along through the snow. Others are intense and terrifying, still others gentle and almost pastoral, if here and there a trifle sweet.

It is fourteen years since The Sun Also Rises and eleven since A Farewell to Arms. More than three hundred years ago John Donne said, ‘No man is an Iland, intire of it selfe; every man is a peece of the Continent, a part of the maine. And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.’ Mr. Hemingway has taken this text and, out of his experiences, convictions and great gifts, built on it his finest novel.”

–Ralph Thompson, The New York Times, October 21, 1940

Across the River and Into the Trees (1950)

I would take anything I love and throw it off the highest cliff you ever saw and not wait to hear it bounce.

“The most important author living today, the outstanding author since the death of Shakespeare, has brought out a new novel. The title of the novel is Across the River and Into the Trees. The author, of course, is Ernest Hemingway, the most important, the outstanding author out of the millions of writers who have lived since 1616.

…

It is not unfair or unjustifiable, this casting of the novel’s characters. The novel was written as a serial for Cosmopolitan, whose demands and restrictions are I should say, almost precisely those of the movies. Now that the novel is available between boards, a great many touches that most likely were in Hemingway’s working manuscript have been restored. They don’t add much, they don’t take much away. At the same time they do make a difference: they make the bound volume authentically Hemingway, and not Hemingway plus (or maybe minus is the word) the Cosmopolitan editors.

…

“In the new novel, Hemingway, rather regrettably, has done nothing to protect himself against personal attack, or, more accurately, counter-attack. He has named some names, and made easily identifiable some others: Patton, Eisenhower, Montgomery, Ney, Custer, Truman, Dewey, as well as an author or two, a journalist or two, and probably a few non- celebrated individuals who will recognize themselves or think they do.

This does not sound like a roman ý clef, any more than it is an autobiography (Hemingway is still alive, and Dick Cantwell ends the book by dying), and that doesn’t matter either way. What matters is that Ernest Hemingway has brought out a new book.

To use his own favorite metaphor, he may not be able to go the full distance, but he can still hurt you. Always dangerous. Always in there with that right cocked.

Real class.”

–John O’Hara, The New York Times, September 10, 1950

The Old Man and the Sea (1952)

Let him think that I am more man than I am and I will be so.

“The Old Man and the Sea is a short novel, only 27,000 words. It is much simpler and enormously better than Mr. Hemingway’s last book, Across the River and Into the Trees. No phony glamour girls and no bullying braggarts sentimentalized almost to parody distort its honest and elemental theme. No outbursts of spite or false theatricalism impede the smooth rush of its narrative. Within the sharp restrictions imposed by the very nature of his story Mr. Hemingway has written with sure skill. Here is the master technician once more at the top of his form, doing superbly what he can do better than anyone else.

…

“Mr. Hemingway has always excelled in describing physical adventure and the emotional atmosphere of it. And many of his stories have glorified courage in the face of danger. This one does, too, for the old man is the very embodiment of dogged courage.

…

“But good as The Old Man and the Sea is, it is good only in a limited way. The fisherman is not a well-characterized individual. He is a symbol of an attitude toward life. He often thinks and talks poetically and symbolically and so artificially.”

–Orville Prescott, The New York Times, August 28, 1952

Islands in the Stream (1970)

Being against evil doesn’t make you good.

“Devious and secretive, Islands in the Stream is an elaborate refusal to say what is the matter with Thomas Hudson. It calls him Thomas Hudson throughout, which makes the reader’s relationship with him at once utterly stable and aloofly unadvancing. The book makes it impossible for us to know what is the matter with him (and so at the same time to know what was the matter with Hemingway) by an ingenious circumvention: it proliferates good reasons for him to be in a bad way. What—it asks incredulously—is the matter with him? Haven’t his marriages broken up? Doesn’t he still despairingly love his first wife? Aren’t all his sons killed? Isn’t his work as a painter threatened by drink and indiscipline? Isn’t he enduring the joyless dangers of furtive seamanship in a war which seems merely six of one and half a dozen of the other? What more do you want? Well, yes: but apart from the ‘work’ one (which doesn’t ring true but does ring revealingly false), all of these stand rather as ex post facto constructions than as living pains. The great swordfish here escapes; the mighty fish which Hemingway here most adroitly lands are indeed prize-winning specimens but are red herrings.

…

“And the other horse that Thomas Hudson was riding now? A bankrupt duty, that of pursuing those Germans. Gone is Hemingway’s old vengeful zest of which Edmund Wilson wrote so piercingly (‘indulgence in that headiest of sports: the bagging of human beings’)—and a good thing it is gone. But what is left is not the disinterested but the uninterested. ‘Get it straight. Your boy you lose. Love you lose. Honor has been gone for a long time. Duty you do.’ But so truncated and impoverished a notion of duty does not do its duty: it—and in both ways—does for duty.”

–Christopher Ricks, The New York Review of Books, October 8, 1970

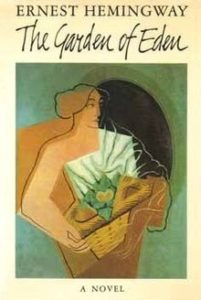

The Garden of Eden (1986)

You’ll ache. And you’re going to love it. It will crush you. And you’re still going to love all of it. Doesn’t it sound lovely beyond belief?

“The propriety of publishing, as a commercial endeavor, what a dead writer declined to see into print is, of course, dubious. The previous forays into the Hemingway trove have unfortunately tended to heighten our appreciation not of his talent but of his psychopathology.

…

“There is every reason to distrust The Garden of Eden; yet the book, as finally presented, is something of a miracle, a fresh slant on the old magic, and falls just short of the satisfaction that a fully intended and achieved work gives us…The basic tensions of the slender, three-cornered action are skillfully sustained. The psychological deterioration of the heroine, Catherine Bourne, the professional preoccupations of the hero, the young writer David Bourne, and the growing involvement of the other woman, Marita, are kept in the fore, interwoven with but never smothered by Hemingway’s betranced descriptions of the weather, the meals, the landscape, the chronic recreations. A chastening, almost mechanically rhythmic order has been imposed, and though an edition with a scholarly conscience would have provided some clues to the mammoth amounts of manuscript that were discarded, this remnant does give the reader a text wherein he, unlike the author in his travails long ago, never feels lost.

…

“The Garden of Eden adds to the canon not merely another volume but a new reading of Hemingway’s sensibility. Except in some of the short stories and that strange novel To Have and Have Not, he avoided describing the life that most men and women mostly lead, domestic life. The Garden of Eden confronts sexual intimacy, marriage, and human androgyny with a wary but searching tenderness that amounts, for a man so wrapped up in masculine values and public gestures, to courage.

…

“Though The Garden of Eden, like the other Hemingway remnants, has its psychopathological aspect, the pathology is caught up into a successful artistic design. Hemingway’s heartfelt sense of women as the root of evil enforces and energizes the allegory. Catherine’s transformation from sexually docile Eve into caustic and destructive bitch, makes her the most interesting of his heroines; unlike the martyred Catherine Barkley of A Farewell to Arms, she does things instead of having them done to her, the perpetrator and not the victim of ‘a dirty trick.’ Her advancing derangement, with its abrupt backslidings into affection and docility, produces some of Hemingway’s sharpest pages of dialogue; like Bellow’s feral females, she becomes vivid and glittering in antagonism.”

–John Updike, The New Yorker, 1986