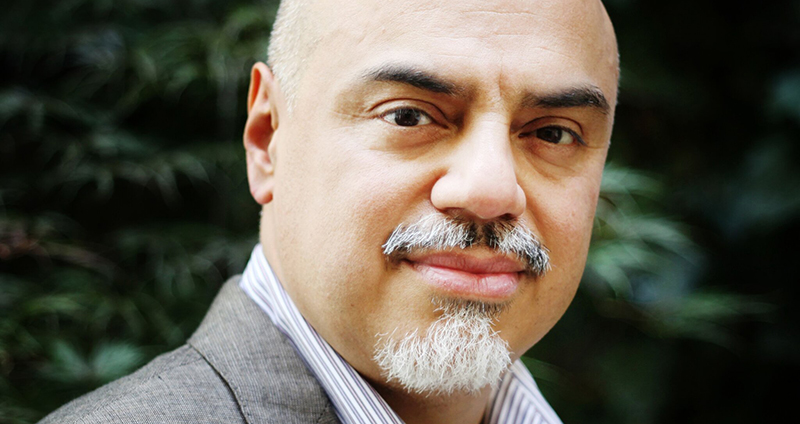

Héctor Tobar on Collaborating With a Dead Man

In Conversation with Sean McDonald on the Well-Versed Podcast

This week on Well-Versed, Sean McDonald, publisher of MCD, talks with writer Héctor Tobar about his new novel, The Last Great Road Bum, the great road novels in literature, his real-life allegiance to Joe Sanderson and his family, and publishing a novel at the current moment.

From the episode:

Sean McDonald: Hector, hello. We’ve been working together for a very long time now. And I was just thinking about how the first book we worked on together was a nonfiction book called Translation Nation. The New York Times called that book something like “Che Guevara as Motorcycle Diaries crossed with Alexis de Tocqueville.” It occurred to me that that in some ways is an accurate description of The Last Great Road Bum, too, that there’s this radical politics. There’s the road trip quality of the story and this sort of tour of America and extra explication of the ideals. Does that seem right to you? Do you feel like we’ve come back around to that project, or is that always been the Héctor Tobar project?

Héctor Tobar: Well, I really feel now that you mentioned it, that that book really Translation Nation in many ways foreshadows some of the themes and the concerns of this book. You know, in Translation Nation, I travel across the United States and it was basically me learning my country, born in America and carrying a U.S. passport. I sort of learned in that book how incredibly diverse and interesting the United States is as a country. And this book, The Last Great Road Bum, is about discovering the world right through the eyes of Joe Sanderson. Joe Sanderson leaves Urbana, Illinois, and heads off into the world and discovers civil wars and revolutions and beautiful people all over the world—and definitely the politics. I was the protagonist of Translation Nation, someone who had been raised by a radical left dad. And Joe is from a Republican family, but becomes a radical left, through the things that he sees in the world. So there’s definitely a lot of parallels between the two works.

Sean McDonald: I will admit that I was surprised when you described this as as your next project, though, it all makes sense to me when we follow Joe into the mountains and in El Salvador and he becomes a guerrilla. But I was curious if you could talk a little bit about how you came to the project and why it felt like your next book after Deep Down Dark?

Héctor Tobar: Well, I started working on this two books ago in 2008. I was still a correspondent for the L.A. Times in Mexico City, and one of my areas of responsibility was Central America. It’s one of the secrets of being a foreign correspondent is that you have help, and so I had a fixer, an assistant based in San Salvador, who would call me every week with story ideas. And one day he called me and said, hey, I went over to the Museum of the Revolution and talked to this guy, Santiago, the guy who ran the rebel radio station during the El Salvador Civil War. And he told me about this diary, that of this gringo. His name was Lucas. That was Joe Sanderson’s nom de guerre. And, hey, that sounds to me like an interesting story.

I immediately thought, Che Guevara’s Motorcycle Diaries and Che Guevara’s The Bolivian Diary. You know, Che Guevara goes into the mountains of Bolivia in 1967 to start a revolution and leaves behind his diary. And I thought, man, there must be a story in that. So I wrote a story about it for the L.A. Times and toyed around with the idea afterwards of writing a nonfiction book. But the nonfiction proposals that I wrote never really seemed to fully come alive. He always seemed kind of pathetic because, you know, he’s a guy trying to write books and never succeeds in writing them. And the stories that were written about Joe right after he died also made him seem kind of pathetic. There was an article in Mother Jones that talks about him as being this lonely figure. And so I put it aside for a while, finished our novel, The Barbarian Nurseries, which came out in 2011.

And then as I was about to start again on my Joe Sanderson project, I was called and reached about the Chilean miners project, so I completed that book. And so finally, when I got back to working on Joe’s book, it seemed to me that I really wanted it to be a novel, because as I looked deeper into Joe’s story, you know, here’s a novel. Here’s a guy who spent his life trying to write novels, all of them unpublishable and very difficult to read. I don’t think I’ve ever managed to read more than maybe a chapter or so of each one of his novels and who, you know, eventually goes around the world trying to be a character in a novel, doing all sorts of crazy things and can never write about it. And so I thought, well, I’m a novelist. I’ve been published. My novels have been translated. I really must be an artist. Maybe I should tackle this as a work of art. So I drove into it, and one of the lessons you learned from writing novels is that you have to write about the complete person. You have to be and know the whole person. So I took a deep dove into Joe Sanderson’s life and went all the way back to his boyhood in Urbana, Illinois.

Sean McDonald: What was the level of your personal connection with Joe? I mean, you just referred to it as Joe’s novel. Did you see parts of yourself in him? Did you see the way he traveled is something that you’ve done or wanted to do with those adventures, his way of trying to write a novel? Did that seem as bonkers to you?

Héctor Tobar: Well, assomeone now in his 50s and someone who’s written five books, the way he tried to go about writing a novel was bonkers. But I really did identify with him as a twenty-year-old. That’s the kind of twenty and thirty year old I would have been if I was crazy. If I didn’t have any inhibitions, I would have been somebody like Joe Sanderson. Maybe if I was also was a white boy from a university family who didn’t have to worry about the pressure of impressing his immigrant father and immigrant mother and living up to their expectations. Joe routinely frustrated his parents and frustrated them again and again, and it’s really interesting because in the course of the novel, I think I identify with Joe’s mom as much as I identified with Joe. So I really had a lot of fun writing about her own sort of frustrations with her college age son who drops out of college.

I think I saw Joe, and really the thing I most identified with was his joie de vivre. His unflappable way he approached traveling to all these crazy places, and also his sense of humor. I really, really enjoyed his sense of humor, and if you notice in the book, his wry sense of humor in his letters. To me, it’s this incredible cache of letters, and I’m doing my best to keep up with him. We’re kind of riffing off of each other, and I came to think of it like this collaboration with a dead man. He left behind all of these great riffs that are just a total mess. The whole thing is a mess, but my job is to bring order to it. We were riffing together as human beings and as observers of the craziness of society.

Sean McDonald: Are you well-versed in the likes of Kerouac and the sort of great road novels that everyone refers to? Or is that something you came to now?

Héctor Tobar: Well, you know, I read On the Road again as I was writing this book and … it was a really lovely work. I did read, you know, Truman Capote referring to it as that’s not writing. It’s typing. So there’s a kind of rough quality. But to me, it feels really like a documentary work, which jibes a lot with with with The Last Great Road Bum and Joe’s project. The thing, too, about On the Road is how much is hidden. You know, there’s a whole homosexual love story going on in there between two of the characters that’s completely closeted, and Joe’s book is written in the here and now. We live in this time when all of these barriers have been broken. We live in a time when feminism has really changed the way we think about our relationships, but also about art and literature. That was part of the challenge of it. It would have been a boring book if I had tried to write it a little bit, just completely from Joe’s perspective. So how can I step out? How can I be the women that Joe fell in love with? How can I be his mother? How can I be those those Third World peoples that he met? I have to be them, which is something that Kerouac didn’t do. In On the Road, Kerouac meets this Mexican-American woman in California and has an affair with her and then she leaves the book. We don’t really know much about her. It’s a very shallow portrait of her in the book. … The world has changed. So that was part of that. That was a big part of it. Although, you know, those books are just this powerful American tradition. The other book that I read, that for me is the greatest road book is Huckleberry Finn. Just building on that tradition to me was a lot of fun, and also taking it in new directions.

Sean McDonald: Absolutely, and I think I think you can feel that for sure. Was it a complicated decision for you to to write this book about Joe Sanderson, a white guy? Did you feel like you were taking a strange turn, or did it feel it would be easy and natural?

Héctor Tobar: It always felt like I was committing a transgression, but not a transgression against Joe. Although there are times when I thought I’m stealing his story. And actually Joe says that in the book, this watermelon guy is stealing my story. I was committing a transgression against what I was supposed to be doing and that I was going out into this territory that was really dangerous, you know, writing a novel about a white guy. But at the same time, that’s what I liked about it. I like the challenge of writing about Urbana in the 1950s because I can sort of feel it. I could sort of feel Urbana in the 50s and 60s because I grew up in the late 60s, and I can feel the media of the time. I could just feel the optimism of the time. I remember that really vividly. Those are my earliest memories of the United States, of this country of incredible optimism and kind of an innocence, too. And so it felt like something that I had a little bit of ownership with. I could own that story, too.

At the same time that it felt like, you know, that people would be questioned. Why are you spending your time doing this? We need you to be writing about El Salvador or some village in Mexico. Why are you dedicating this time? It just seemed like almost like I was engaged in this sort of luxurious, kind of wasteful behavior of my time. I just always felt like there was something there that I could hold onto, which was being a boy in the United States. And that boy, his boyhood to me, was something that I really reveled in, maybe a little bit too much at first. I had to scale it back a little, but it was something that I did feel like I was going out on a little bit of a limb.

Sean McDonald: One of my favorite parts of the book has always been the interplay between Joe, as character, and you, as author, which actually ends up taking taking place a little bit in the margins, I guess. Which obviously leads to wondering about what you write up earlier about the nature of it being a novel and what kind of allegiance you have to Joe. You’ve talked about the letters. But when you decided it was fiction, was that liberating or did you continue to feel this kind of obligation to Joe? I know you also stayed in touch with this family.

Héctor Tobar: Yeah, it was absolutely liberating to write it as fiction just because then I could enter into the experience as a kind of dream. I’m trying to recreate the dream of being this American boy and then later this American man. So it was completely liberating at the same time. You know, in this novel, perhaps more than any other novel I’ve written, I really did work a lot as a journalist. I did a ton of research. I interviewed Joe’s hundred-year-old father for four days. I spent four days with this man in Pennsylvania. It was wonderful. It was also really important for him to unburden himself because, you know, he lost his son when his son was thirty-nine years old and lost his son at a relatively young age. He had a lot to unburden himself of. Every place I went, I visited in the novel, I tried to recreate and to be really precise. I think I’ve never really quite worked that way, completely trust trying to be so, so precise, and especially in places that are really far away from my own experience,

The whole novel part of it, that was definitely the beating heart of it: that I am going to become this person. And it really did seem to flow once I got going. When you write a novel, you become the person. And so I became Joe, and it was a tremendous amount of fun. At the end of the novel, when I had to say goodbye to Joe, I guess it is pretty clear that he’s died, you know, I cried. I cried when I wrote the last sentence, Joe’s last sentence. It was a really wonderful emotional process when people have asked me about how you rose to the challenge of writing about Joe.

_________________________________

Héctor Tobar is a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and novelist. He is the author of the New York Times bestseller Deep Down Dark, as well as The Barbarian Nurseries, Translation Nation, and The Tattooed Soldier. Tobar is also a contributing writer for the New York Times opinion pages and an associate professor at the University of California, Irvine. He has written for The New Yorker, the Los Angeles Times, and other publications. His short fiction has appeared in Best American Short Stories, L.A. Noir, ZYZZYVA, and Slate. The son of Guatemalan immigrants, he is a native of Los Angeles, where he lives with his family

Well-Versed

Even in times of stillness and physical distance, reading a great poem has the ability to move us, transport us—in other words, poetry will always retain its power to feel, as Lowell says, like an event. On Well-Versed, we’ll be commemorating the art of verse, with original recordings, conversations with poetry luminaries, and more.