Why would you do such a thing? That is not a good idea.

But no one knows, and so no one asks.

Why in the night I slip from the rear of the darkened house. Why making my way along the graveled drive to the highway where in the shadows of evergreens I stand watching for headlights on Transit Road.

Sometimes there is a light rain. Overhead, a mottled sky and a fierce glowering moon-face behind clouds.

Like a sleepwalker who has wakened. In the night, past midnight, in this place in which such behavior would be perceived (by adults) to aberrant, in a way rebellious.

It is disturbing to the adults of a household, when we are not in bed at the proper time. Our sleep, they can’t control or monitor; how far we wander in our dreams, they have no idea. But it is an audacious gesture to leave the sleeping house and to venture outside, alone.

Insomnia begins in early adolescence. The swarming brain, the fast pulse. Excitement in realizing—Something is about to happen!

Out of nowhere has come this strange fascination that will endure for years, until I move out of the house on Transit Road forever.

A fascination with prowling in the night—standing at the end of the gravel driveway—watching for headlights of strangers’ vehicles as they first appear beyond the V-intersection of Transit Road and Millersport Highway (to the south) and beyond the bridge over the Tonawanda Creek in the direction of Lockport (to the north). Lights that are scarcely visible at first, like faint stars, gradually growing larger, and then more swiftly larger, as if the vehicles were accelerating, and the headlights near-blinding—until abruptly the vehicle has passed, and now it is red tail lights that are visible, receding.

Of all vehicles, Greyhound buses at night seem most fraught with romance. For I am often a passenger on these buses, riding to Lockport and back to Millersport, but mostly by day; rarely by night. (The bus station in Lockport, on a back street that runs parallel with Main Street, is not a place of safety or comfort for a girl or indeed a woman traveling alone after dark.)

Why am I entranced by headlights on Transit Road? Is it the contemplation of sheer randomness, chance? The intersection of lives—by chance? The life of the mind is essentially a life of control; if you are a writer, it is control which you bring to your work, by way of the selection of language, the arrangement of “scenes,” the achievement of an “ending”… But life is likely to be that which lies beyond our control, and is unfathomable. And so I am entranced by the phenomenon of strangers’ vehicles speeding past our house, that would elicit scarcely a glance by day.

There is something melancholy about this memory. The girl is a figure in a Hopper painting that Hopper never painted. The girl is in disguise as a (young, mere) girl—that is the explanation.

It is at such times that I feel my aloneness most strongly—which is very different from loneliness.

Loneliness weakens. Aloneness empowers.

Aloneness makes of us something so much more than we are in the midst of others whose claim is that they know us.

If they have named us, it is reasonable for them to believe not only that they know us but that they own us.

It is a peculiar fact of my young life, that I am under the spell of the Other; mesmerized by the prospect of mysterious lives that may surround me, to which I have no (actual, literal) access. The phantasmagoria of what is called “personality”—why we are, but also why we are so very different from each other.

When I am alone I think of such things. Especially when I am alone at night. Restless in my room, which is now, after my grandfather’s death, a bedroom on the first floor of the farmhouse, with a single small window overlooking a small patch of outdoors. To see the night sky, I have to kneel at this window and crane my neck to look sharply up. Often there is nothing to see for the sky is opaque with clouds.

* * * *

It is possible that my wandering outside at night has begun in reaction to my grandfather’s death. For this is the first death.

It is possible that this early insomnia, a restlessness of the brain, a sudden and profound wish not to be in bed, with bedclothes weighing down my legs and feet, has something to do with the first death.

A death in the family is an abrupt and awful absence. A presence as familiar to you as your own face in the mirror is suddenly gone.

Like stepping through a doorway, and there is no floor, nothing awaiting—you will fall, and fall.

The first death is a realization you cannot accept, as a child: that it is but the first, and there will be others.

The farmhouse, the farm buildings, the blacksmith’s forge in the barn—all are linked so closely with my grandfather John Bush, it is scarcely possible to imagine these without him.

Yet, these will remain. The smithy’s equipment, layered with soot; in a corner of the old barn, a pile of broken horse shoes.

Long after my grandfather is buried in the Good Shepherd Catholic Church cemetery, these will remain.

It was his time it was said.

John Bush died mysteriously—so it seemed to me. Suddenly my Hungarian grandfather was coughing more frequently, and more terribly, than before; his brash, bullying manner faded, and even his physical bulk seemed to diminish. My grandmother was no longer dominated by her forceful husband but rather terrified of what was happening to him, that took her, too, by surprise.

Emphysema, it was said. Ruined lungs, bleeding from tiny particles of iron, polluted and corrupted air breathed for years at Lackawanna Steel.

Nothing to be done, it was his time.

I am too young and too frightened of my grandfather’s absence to wonder at this death. Far too young, to wonder why John Bush who was so canny and obstinate yet had to work in such conditions. Why he felt he’d had to work in such circumstances. Decades later such a death would be designated work-related.

But for now the peasant fatalism—His time.

I am too young to be angry on the behalf of my grandfather. In time, perhaps. But not now.

For now, it is enough to make my way through the darkened sleeping house, very quietly open the back door, and step outside into the night… Sometimes, one of the cats will approach me. There is that curious way in which a cat will approach you when you appear outdoors at an unexpected time, with a kind of animated intensity, and an inquiring mew. As if for a moment there is some confusion of categories, and the cat must determine if you are (still) a person, or in some way a cat. Is this one of me?

It is the headlights that captivate, on the road. The mystery of how vehicles seem to arise out of nowhere in the night and pass by me oblivious of me. I am hidden, and invisible. Yet I am here—and why? What has drawn me? Is it important somehow that I am here, and not in my bed?

Most of the nighttime vehicles are cars. Mostly, there is but a single person visible in them—the driver.

But sometimes I catch a glimpse of a second person in the passenger’s seat and I feel a sudden pang of envy—Who are you? Why are you driving together late at night? Do you love each other? Is that why you would be together late at night—because you love each other? And why are you driving along Transit Road? What do you look like, what are you thinking, where do you live, where are you going…

In the next instant, red tail lights receding.

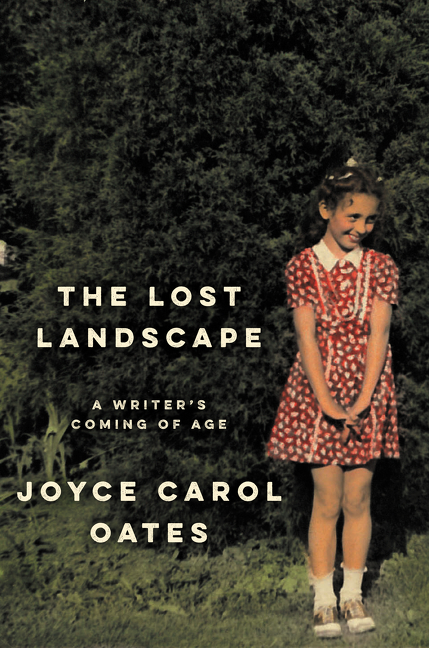

From THE LOST LANDSCAPE. Used with permission of Ecco. Copyright © 2015 by Joyce Carol Oates.