Growing Up in One of America's Legendary Restaurants

Fanny Singer on Her Mother's Place, Chez Panisse

All photos by Brigitte Lacombe.

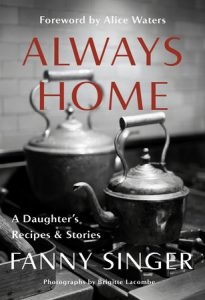

A few weeks ago, maybe, I could have written something very different, something about the role that food has played in my life, or about what it was like growing up in proximity to culinary eminence, or even just about my uniquely delicious childhood—and, if you’re curious about those aspects of my upbringing, many such stories can be found in my new memoir, Always Home, which came out yesterday.

But at the moment, well into the third week of quarantine—or is it the fourth? Time passes so differently now—my perspective has shifted somewhat. When I was writing the chapter dedicated to my mother’s restaurant Chez Panisse, it was with a certain blithe confidence, a taking-for-granted that it would be operational throughout the balance of my life, and perhaps well beyond. It’s that kind of place: an heirloom, really, not a business—a restaurant that knits together generations and community around a common cause.

On the whole, I would describe Chez Panisse as more European than American (even if it’s often credited with innovating “California Cuisine”). European restaurants stay in the family for hundreds of years. They also tend to sit at the hearts of their communities, becoming de facto meeting halls, hosting marriages and graduations, and of course catering to their weeknight regulars.

Chez Panisse, which my mother founded in 1971, was inspired by those types of establishments. As a university student studying abroad in France, she’d filled countless hours in such places, drinking from unmarked bottles of house red, or hard cider, eating something simple and delicious prepared from ingredients grown on or near the premises.

Later, when she began watching Marcel Pagnol’s 1930s-era films depicting the archetypal dramas of Provencal life, she became obsessed with the idea of opening the kind of restaurant that could anchor a place, become its principal cultural artery. Chez Panisse was from the very beginning a community undertaking, started by a band of friends as seduced by the flavors of provincial French cuisine and the type of conviviality it implied, as they were indoctrinated by the burgeoning local ‘grow your own’ and ‘Food Conspiracy’ movements (which advocated for more equitable distribution of, and access to, organic, wholesome food).

The Berkeley Free Speech movement and its figurehead Mario Savio were likewise an inspiration; despite its ‘restaurant veneer,’ Chez Panisse was really conceived as a gathering place. Of course, when the restaurant opened, the Vietnam War still dominated the national consciousness—adding a sense of urgency, of political necessity even, to the creation of an environment in which members of the counterculture (whether activists, or artists, or hippies) could convene. My mom insisted, however, that above all the food must be delicious. A fusion of rustic French culinary sensibilities and the defining attitudes of the Berkeley culture of the sixties and seventies—it was the beginning of her ‘Delicious Revolution.’

What I wrote about Chez Panisse in Always Home was nostalgic, but not intended to be elegiac.

I wasn’t alive for any of this—I was born twelve years into the life of the restaurant—but even a decade after that, as I began to grow more alert to its operations and management, its radical roots were still evident. For one, it had an unusually democratic structure, a non-traditional hierarchy that couldn’t be found elsewhere—there were, and remain, four chefs with equally shared responsibility and agency.

My mother also started a project centered on food justice, now in its 25th year, called the Edible Schoolyard, a garden and kitchen classroom woven into the pedagogical fabric of Martin Luther King Jr. Middle School, a nearby public school (the program is now one of thousands seeded at affiliate schools worldwide). There was a productive sense of agita in our household, and at the restaurant too—my mom wanted things to be just right (whether it was something as slight as the wattage of a light bulb in the dining room, or as significant as guaranteeing access to “good, clean, fair” food for all children in the Berkeley Unified School District. She’s working on the whole of the State of California now. Next up: the world).

Photo by Brigitte Lacombe.

Photo by Brigitte Lacombe.

What I wrote about Chez Panisse in Always Home was nostalgic, but not intended to be elegiac. They are stories about growing up knowing a business as intimately as a home, about internalizing its every detail, down to its profusion of smells: the astringency of the cedar that paneled the cloak closet; the ripe fruit coming to its peak stored on the shelves of an outdoor breezeway in the summertime; the acidic bite in the air as a prep cook whisked vinegar into a dressing for the dinner service; the smell of a blazing fire coloring a pizza in the wood oven.

My knowledge of the place was like different layers of a map: overlaying the olfactory blueprints were the memorized oddities of the building’s architecture. I knew the best nooks for games of hide-and-seek, performed with whoever was willing to engage; from which shelf in the walk-in refrigerator a selection of pastries could be pilfered; where to go for a length of twine, an empty cardboard box, ice cubes, a fresh apron, a bottle of Tylenol. And yet, in light of the recent pandemic, the restaurant has been closed for more than two weeks now, and its future has never been so precarious.

So it’s in this strange new climate, in which the air seems practically to thrum with uncertainty, that I’m writing from the small table at the back of my mother’s dining room. It’s the smaller of the two tables in the room (which is really the same room as the kitchen; my parents knocked down the wall that separated the two when they bought the house in the early eighties), and it sits next to the glass French doors that open onto a shallow balcony overlooking the back garden. From where I’m perched, the canopies of all the fruit trees (quince, cherry, apple) fill the view, more densely flowered this year than ever. When summer arrives there will be a bumper crop, though any future season feels surreally distant.

Even when you are not physically in the place you most associate with home, you can cultivate a sense of ease, of beauty, of calm, that can help you feel oriented wherever you are.

I called my book Always Home because I wanted to write about how the notion of home sits it the mind, and in the spirit. About how, even when you are not physically in the place you most associate with home, you can cultivate a sense of ease, of beauty, of calm, that can help you feel oriented wherever you are. I lived away from Berkeley, from Chez Panisse, from my mother, for the better part of sixteen years, from the time I was in college on the opposite coast, through a decade and some in England, where I lived from 2006. Throughout that time, during which I was cooking at home avidly and frequently, I was nonetheless looking to carve out some intellectual distance from my mother. I studied art history, wrote art criticism (which I still do), and made a life thousands of miles from the world my mother had created.

Photo by Brigitte Lacombe.

Photo by Brigitte Lacombe.

Still, I wanted to hold her near me. I wanted to feel close to the things that had shaped my childhood and my adult sensibility. My mother always says that “beauty is a language of care,” which suggests the genuine indispensability of beauty—beauty is not something one can dismiss as trite or trivial; it is an atmosphere of love that cradles us. To use a Winnicottian turn of phrase: it is essential to the provision of ‘ordinary care.’

It is inconceivable to me that Chez Panisse might not reopen after this once unimagined siege—I have to believe that it will. Throngs of people will gather there again soon, and take all the learnings from this time to foment new revolutions. But, staring out at my mother’s lettuce patch in a garden impervious to the news—bees are buzzing, birds chirping, squirrels nibbling the fraises de bois (no wonder the yield is so low!)—the question of what can make us feel grounded and sane, what might constitute ordinary self-care at a time so pregnant with precarity, feels most exigent. There’s nothing we can do, really, to change the shape of this period, other than to hold still…and to cook, of course, with all the vegetables and fruits that our local sustainable farmers still need us to buy.

There’s one other thing you can do: take a branch of rosemary from the bush in your back yard, or from the one overtaking the sidewalk in front of your neighbor’s house, or maybe just pick some up at the market. Set it alight with a match and trail it like incense through your home. There is something about its heady, purgative aroma that will bring you back into your body. In our family, that smell, that sudden jolt of self-awareness: it’s the feeling of being home.

_______________________________________

Fanny Singer’s Always Home: A Daughter’s Recipes & Stories is out now from Knopf.

Fanny Singer

Fanny Singer is a writer, editor, and co-founder of the design brand, Permanent Collection. In 2013, she received a Ph.D. on the subject of the British pop artist Richard Hamilton’s late work from the University of Cambridge. In 2015, she and her mother, Alice Waters, published My Pantry, which she also illustrated. Having spent more than a decade living in the United Kingdom, Fanny recently moved back to her native California. Based in San Francisco, she travels widely, contributing art reviews and culture writing to a number of publications including Frieze, The Wall Street Journal Magazine, Apartamento, T Magazine, and Art Papers, among others. Her new book, Always Home is out now.