Ghosts, Demons, and Depression: Writers and Their Many Hauntings

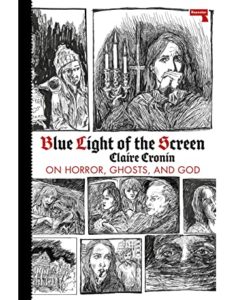

Claire Cronin on the Literary Fixation on the Supernatural

Avery Gordon writes: “To be haunted and to write from that location, to take on the condition of what you study, is not a methodology or a consciousness you can simply adopt or adapt as a set of rules or an identity; it produces its own insights and blindnesses. Following the ghosts is about making a contact that changes you and refashions the social relations in which you are located.”

I only wish to be obedient to this thread of sight, this line of thought, this longing. I worry that my interests are like Faust’s: I want to know the secrets of hell. Or they are like Fox Mulder’s: I want to believe.

I think it’s far more frightening to hesitate than know. The uncertainty of a ghost’s existence is why the ghost story scares us. In the presence of spirits, we are called to doubt our minds and senses, and a horror of interpretation lingers after images and text. This makes the ghost story the paradigmatic horror narrative rather than a misfit of the genre.

Philosopher Noël Carroll doesn’t think most ghost stories belong in horror, calling them uncanny “tales of dread” or “pure fantastic” plots, depending on how much faith we’re made to feel at the narrative’s conclusion. If a story hesitates between supernatural and naturalistic explanations for its ghosts, then Carroll claims it fits within Tzvetan Todorov’s genre of the fantastic. The Turn of the Screw, Carroll writes, is a perfect example of this type, for it offers an ambiguous ending. Were the children really haunted by the ghost of their old governess, or has the new governess, who tells the story from her perspective, lost her mind because of the isolation and repression of her workplace? Thousands of pages of criticism and thousands of hours of classroom discussion have been spent on this puzzle.

The same questions are raised by Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House—another novel Carroll exiles from horror. Did the troubled woman kill herself because the spirit of the house willed her to do it, or did she finally succumb to mental illness? “Her thoughts are obsessive and detached in a way that could indicate either possession or madness,” Carroll writes about this character, though he admits that the book tempts readers to believe in a supernatural cause.

The proof that Carroll wants at the end of a horror story comes through sight. He is a scholar: a spectator. He writes that in satisfactory horror plots of any medium, “once the supernatural agent is shown, that’s it; there is no further question of its existence.” Such evidence seems easier to give in film and TV ghost stories, where ghosts are things we see, though many horror movies end with the revelation that a monster was really a character’s delusion. Or, through camerawork and editing tricks, the supernatural is kept just out of frame and hinted at through shadow, sound, and frightened faces. Images, like language, can mislead. What Carroll seeks in horror—a genre about our fears of the unknown—is a kind of certainty.

In the presence of spirits, we are called to doubt our minds and senses, and a horror of interpretation lingers after images and text.

But ghost stories are hovering uncertainties. So fear is also faith, or the liminal half-faith that comes instead.

The poet Rilke is said to have developed psychic abilities during a period of illness in military school. One study of his life claims that a “fit of vision” lead to his psychokinetic and telepathic powers, as evidenced by an incident where Rilke mentally shoved a boy who was bullying him. As an adult, Rilke liked to communicate with ghosts. While staying at Castle Duino, the home of his patron, Princess Marie von Thurn und Taxis, Rilke often participated in seances with the Princess’ son, Pascha, acting as medium.

Through these sessions, Rilke met a spirit who called itself the “Unknown Lady” and gave the poet very specific instructions for how to escape his creative crisis, telling him to travel to the town of Bayonne to seek her grave and also to Toledo, Spain, to see a specific bridge. Rilke faithfully carried out these tasks. Although his visits to the graveyard and the bridge did not yield further revelations, it was during this time that Rilke began his greatest work, Duino Elegies. “Who, if I cried out,” he wrote, “would hear me among the angelic orders?”

Other writers I admire also communed with ghosts. Jason Molina says he saw spirits of the dead and wrote songs about or through them, though he was known to tell tall tales. Jack Spicer says he received messages from what he called “ghosts” or “martians” and stayed up nights turning their transmissions into poetry. Both artists died young from alcoholism, which is akin to sorrow; Molina was thirty-nine and Spicer was forty.

A psychic friend tells me that it’s common for mediums to have addiction problems, though he doesn’t know why. “Maybe the ghosts do something to your blood sugar.” “Maybe it’s because you need to ground yourself back in your body after a session.” “Maybe those people just want to escape; to turn it off.”

In one of his songs, Jason Molina sings: “While I lived I was a stray black dog.” In another, he sings: “Let me go, let me go, let me go.”

“Poet, be like God,” Jack Spicer wrote.

But ghost stories are hovering uncertainties. So fear is also faith, or the liminal half-faith that comes instead.

Sylvia Plath, whose tragic end we know too much about, is rumored to have been possessed by evil forces in her final months. Ted Hughes encouraged her to use Ouija boards and hold seances and Plath became obsessed with tarot cards. After Hughes’ affair and the couple’s separation, Plath was said to have cast revenge spells on him. According to one legend, Plath wrote Ariel while under the influence of magic. Awakening at 3am most nights, poems were delivered to her from some dark, unseen author.

There is a piece about this in The Guardian which is descriptively titled: “How black magic killed Sylvia Plath: Ted Hughes’ dabbling in the occult enabled his wife to write some of her greatest works.” In Plath’s poem “Little Fugue,” she tells us: “Death opened, like a black tree, blackly.”

In Thomas Merton’s autobiography The Seven Storey Mountain, readers are told of Merton’s conversion to Catholicism through a ghost story. He writes:

I was in my room. It was night. The light was on. Suddenly it seemed to me that Father, who had now been dead more than a year, was there with me. The sense of his presence was as vivid and as real and as startling as if he had touched my arm or spoken to me. The whole thing passed in a flash, but in that flash, instantly, I was overwhelmed with a sudden and profound insight into the mystery and corruption of my own soul, and I was pierced deeply with a light that made me realized something of the condition I was in, and I was filled with horror at what I saw.

Merton’s life is changed in this moment. He cries, he vows, he prays, he begins to visit churches. He is certain that he felt his father visit him and this feeling makes him sure of the existence of the human soul. In the next chapter, Merton has gone so far as to experience the thought “I should like to become a Trappist monk,” which then becomes his fate.

And yet Merton’s ghost story—which, like many ghost stories, is inset in a larger book—remains a shade outside of faith. Merton assures his readers (and a committee of censorious monks): “I do not offer any definite explanation of it. How do I know it was not merely my own imagination, or something that could be traced to a purely natural, psychological cause—I mean the part about my father. It is impossible to say. I do not offer any explanation. And I have always had a great antipathy for everything that smells of necromancy.”

When researching occultism in French Symbolist poetry, I come across a dusty maroon book in the library shelves: The Way Down and Out: The Occult in Symbolist Literature, written by John Senior and published by Cornell in 1959. Unlike so many other academic texts I’d read on poetry and magic, this author treated his subject with graveness and humility. He not only gave a thoughtful analysis of the imagery in Charles Baudelaire’s “Les Litanies de Satan,” but genuinely seemed concerned about the poet’s soul.

Hoping to read more about occultism from John Senior, I searched the author’s name and discovered that Senior underwent a dramatic conversion to Catholicism shortly after his book’s publication. Senior built a career as a humanist, religious traditionalist, and cultural critic, becoming most famous for a book I haven’t read called The Death of Christian Culture. It seemed that he regretted ever writing this early text. Did Senior discover something malevolent through his occult research and did this frighten him towards the Church?

Hoping to read more about occultism from John Senior, I searched the author’s name and discovered that Senior underwent a dramatic conversion to Catholicism shortly after his book’s publication.

I want to think of Senior’s conversion as part of a “professor horror” plot (a subgenre I’ve noticed and named) wherein a skeptical academic discovers, through a rational investigation, that some aspect of the supernatural is true. Or was Senior’s mind loosened by the strange logics of poetry and magic and then easily converted to an equally irrational paradigm?

In the more recent depression memoir, Darkness Visible, William Styron recalls his descent in a demoniac’s terms: “the gray drizzle of horror induced by depression takes on the quality of physical pain,” he writes. “Despair, owing to some evil trick played upon the sick brain by the inhabiting psyche, comes to resemble the diabolical discomfort of being imprisoned in a fiercely over-heated room.”

In Andrew Solomon’s tome, The Noonday Demon: An Atlas of Depression, he quotes a translation of Aretaeus of Cappadocia, a first-century Greek physician, who offers up another mirror. The melancholic “torments himself with superstitious ideas; he is terror-stricken; he mistakes his fantasies for the truth; he complains of imaginary ideas; he curses life and wishes for death.” “To understand the history of depression is to understand the invention of the human being as we now know and are him,” Solomon writes.

In Father Gabrielle Amorth’s book, An Exorcist Tells His Story, a cured demoniac describes his possession this way:

I felt that I was suffering with something other than my body; in fact, I felt that my body was a stranger. I was prey to the strongest despair, and I saw, I know not with whose eyes, a terrible darkness that was not part of the room in which I was or of the bed in which I had lain for months. This darkness was engulfing my future, my ability to live, and any hope of tomorrow. It was as though I were being killed by an unseen knife, and I felt that whoever was pressing this knife hated me and wanted something more than my death.

This feeling is familiar to me.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Blue Light of the Screen: On Horror, Ghosts, and God by Claire Cronin. Excerpted with the permission of Repeater Books. Copyright © 2020 by Claire Cronin.

Claire Cronin

Claire Cronin is a writer and musician currently based in California. She has published poetry and nonfiction and is the author of the chapbook A Spirit is a Mood Without a Body. As a musician, Cronin has released records on independent labels, toured nationally, and been featured in Pitchfork and The FADER.