George Saunders on the Best Writing Advice He’s Received

Everybody's Favorite Literary Uncle Also Loves Gogol

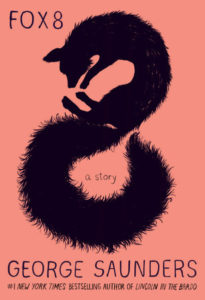

George Saunders’ new book Fox 8 is available now.

*

How do you tackle writer’s block?

I like David Foster Wallace’s notion that writer’s block is always a function of the writer having set a too-high bar for herself. You know: you type a line, it fails to meet the “masterpiece standard,” you delete it in shame, type another line, delete it—soon the hours have flown by and you are a failure sitting in front of a blank screen. The antidote, for me, has been getting comfortable with my own revision process—seeing those bad first lines as just a starting place. If you know the path you’ll take from bad to better to good, you don’t get so dismayed by the initial mess. So: writing is of you, but it’s not YOU. There’s this eternal struggle between two viewpoints: 1) good writing is divine and comes in one felt swoop, vs: 2) good writing evolves, through revision, and is not a process of sudden, inspired, irrevocable statement but of incremental/iterative exploration. I prefer and endorse the second viewpoint and actually find it really exciting, this notion that we find out what we think by trying (ineptly at first) to write it. And this happens via the repetitive application of our taste in thousands of accretive micro-decisions.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

Monty Python and the Holy Grail. It comes out of a very smart place that is political and yet never forgets to entertain and self-lacerate and be silly. For me, a big breakthrough moment when I was able, in my first book, to somewhat reconcile my passionate love for this movie with my desire to “be literary.” What happened was, I saw that this distinction I’d been making between “entertainment” and “literature” was not meaningful, not at the highest levels, if we understand that the real goal is: communication of the urgent. The big scene, for me, was the scene where the king rides past two peasants.

“How do you know he’s a king?” asks one.

“He hasn’t got shit on him,” says the other.

Perfect.

What’s the best writing advice you’ve ever received?

Once, when I was a student, I cornered my mentor and hero Tobias Wolff at a party and assured him that I had sworn off comedic sci-fi and was now writing “real literature.” I think he sensed, correctly, that 1) this was not an attitude that was going to produce my best work but 2) there was going to be no arguing me off of that position (only time could do that). So he just said, “Well, good. Just don’t lose the magic.”

Which I then proceeded to go off and do, for about four years. The “advice” part of that came home on the day I made the breakthrough that would lead to my first book—that is, when the magic (finally) came back. The new writing was fun and (see above) ostensibly entertaining—it came out of a place of joy and orneriness, instead of a place of stiffness or control or pedanticism. And to suddenly recall his advice at just that moment was a sort of force-accelerator, and I’ve never forgotten that, for me, “magic” has to be the operative word—getting the prose to go somewhere and do something you couldn’t have foreseen at the outset.

I saw that this distinction I’d been making between “entertainment” and “literature” was not meaningful, not at the highest levels.So, this principle of proceeding not by head (ideas, concepts, plans) buy by heart (moving ahead line-by-line, trusting my ear, trying to communicate with and entertain an imaginary reader, being ok with being lost and even seeing this as an indicator that the story wants to be more than I have in mind for it) has stayed with me and has led me to think that, when self recedes, there is something else that rushes in to replace it, and that thing is smarter and kinder and just more trustworthy than self, i.e., the self we create through control and rumination.

What was the first book you fell in love with?

It was Johnny Tremaine, by Esther Forbes. My third-grade teacher, Sister Lynette, gave it to me in this very cagey way—basically saying that she’d checked it out for me from the library because she could tell I was bored with the books in class, but (and this was crucial) the other nuns were sort of giving her grief about it, thought it would be “too hard” for me. Catnip! The book is the first one I read that really had style—I could feel that Forbes had been paying attention to every line and also could feel the benefit of that—the book had a physicality I’d never experienced before. I could see a room and smell the food and things that weren’t overtly narrated would spontaneously occur in my mind—a light breeze, a character brushing a strand of hair out of her eyes as she spoke. So this was the first time I felt, dimly, that attention to the sentence directly affected the reader’s ability to be immersed in the fictive world. That is: the sentence made the world, it didn’t (merely) describe it. The other thing that happened was that I started thinking in Forbes’ language and the world changed in response—I saw it differently but also it was different. I noticed differently, through language, as I tried to imitate her. (“Nuns moved across concrete, feet peeking out, clouds gathering low.”) So: an early intimation that style is not just surface and that thought makes the world.

Also, I recently came across a copy of Mr. Cub, the autobiography of Ernie Banks, co-written by Jim Enright and, in reading it, realized how much it had to do with my development as a person, with Banks as a role model. Such a generous, positive person, who recognized that he had lots of responsibility off the field, and always tried to find the best in other people.

Is there a book you wish you had written?

I wish I had written the story “The Overcoat” by Nikolai Gogol. The sensibility of that story is perfect. Gogol somehow manages to make us feel sympathy for the main character without that character needing to be a saint. It makes fun of him while loving him. He’s a stinker, kind of—someone we wouldn’t want to be around and yet, by the end, we feel so protective of him. So Gogol is, I think, modeling, in the prose, a form of Christian love—sort of training us in what it might feel like to really (really) believe that we are all brothers and sisters. And he does this by making us love someone who truly is “the least among us”—not likable, dull, pedantic, who strives for invisibility and, we feel, might not even be particularly kind to someone lower on the totem pole than he is—you feel that, if he could summon up the energy to have a political position, he might be a reactionary. So, that’s a real feat. And it never feels preachy but, is rather, spontaneous and funny and also formally very experimental—it keeps seeming to come to an end and then lurching back alive again.

Also intriguing that Gogol himself was a very mixed bag as a person. He ended up his life as a politically conservative scold, repudiating his earlier, wilder, works of genius. So, I love this idea that we are not fixed, solid entities and will vary throughout our lives and that our best work will happen, possibly, at a time and place not of our choosing and will not necessarily be neatly designed Statements of Purpose but might actually be spontaneous bursts from we-know-not-where, that we’ll later be sorry about.

__________________________________

Fox 8 is available now.