Geoff Dyer Goes Deep on WWII Classic Where Eagles Dare

The Break-Down You Didn't Know You Needed

Do the mountains and the blue Bavarian twilight cause the drum march to rattle into existence—is the music an emanation of the mountains?—or are the peaks and valleys hauled into view by the march of drums? Are these Heideggerian questions, or is it just that the Teutonic opening credits—as red as the background of a Nazi flag—could not be any redder against the mountainous blue of snow-clad mountains and the deep blue sky passing for night? The wind is blowing through the mountain peaks, howling in that snowy, Alpiney way, and the drums are more strident, more martial, and there are possibly even more of them than there were a few moments earlier, marching in formation, flying.

“We were over Germany, and a blacker, less inviting piece of land I never saw,” writes Martha Gellhorn in The Face of War. “It was covered with snow, there was no light and no sign of human life, but the land itself looked actively hostile.” We feel the same, even if the hostile land is not black—but if it was “covered with snow” then it probably wouldn’t have been black when she soared over it in 1945—so the point that needs to be made is that active hostility can look rather scenic too.

An aerial view from a plane becomes a scenic view of the plane, flying in lone formation: seen and heard, propelled by full Brucknerian orchestra now, with a howling tailwind and drums marching so powerfully they could invade the soundtrack of a neighboring cinema. Then it’s a view from the plane again, peak-surfing over the snow-scored mountains, tilting and gliding through the mountain passes, affording Panavision views of . . . Where are we exactly?

Font-wise, as the credits continue to roll, there’s a hint of Castle Dracula and Transylvania—of Christopher Lee and Hammer horror—but the plane is a German plane, a Junkers Ju-52, and it’s giving a very persuasive demonstration of not only its maneuverability but also the excellence of its camouflage as it blends in with the motives for doing a picture like this, which will bring in fabulous amounts of money: so that he can buy his modern-day Cleopatra (“money for old rope” was her verdict on this caper) things like a jet with burnished gold thrones instead of seats.

Or it could just be that he’s nursing a killer hangover (symbolically suggested by the way that, stacked up near him, are what appear to be metal beer barrels), so that as they approach the drop zone he looks at the blinking red light, pulsing like a headache, like a warning of imminent liver failure, and we are suddenly back in the pre-mission briefing room where another red light is flashing—a nice touch by director Brian G. Hutton—as Patrick Wymark (Colonel Turner) gives the briefing as though it’s been scripted not by Alistair MacLean but by William Shakespeare.

Pre-mission briefings are always addressed to the audience as well as the actors gathered around to listen, sitting or standing (Eastwood at the back, half in shadow, a shadowy presence), who are effectively our surrogates, eager to know what we and they are in for. Wymark points with his stick to the map on the wall, to the Schloss Adler, the Castle of the Eagles. Well named, he says, because only an eagle can get in there. He’s right, it (the film) is well named in the way that book or movie titles beginning with “Where” (. . . Angels Fear to Tread . . . the Green Ants Dream) or “When” (. . . Eight Bells Toll . . . Worlds Collide) or (For ) “Whom ” (. . . the Bell Tolls ) always are. Where Eagles Dare anticipates the widespread popularity of the SAS motto “Who Dares Wins,” even though it was made a dozen years before the storming of the Iranian Embassy (1980), of which the film could be seen either as a prophetic allegory or a direct inspiration.

It all depends, I suppose, on what is meant by truth.

And the title is not just a sonorous bit of rhetoric plucked from Shakespeare by producer Elliott Kastner, who needed something better than the “awful fucking title” MacLean had come up with (Castle of Eagles). Kastner’s title cleverly inverts or, as is said in the world of agents and double agents, “turns” the intended sense of the lines in Richard III: “The world is grown so bad / That wrens make prey where eagles dare not perch,” words that Burton could have enunciated with the clarity Larry Olivier would later bring to the voice-over of all twenty-six episodes of The World at War, starting with the famous opening shots of Oradour-sur-Glane (“Down this road, on a summer day in 1944, the soldiers came . . .”), a clarity Eastwood neither attempts nor envies, especially since the English officers in the briefing all look like they’re kitted out in uniforms from the previous war or a shelved episode of Dad’s Army while he lounges at the back in something much sharper, more contemporary, more American-looking, sporting a post-Elvis haircut and wearing the shoulder flashes, as Wymark points out, of the American Ranger Division.

A plane, a de Havilland Mosquito (as featured, a few years previously, in 633 Squadron, about another raid on an otherwise impregnable target),[1] crash-landed near the Schloss where one of the plane’s passengers has been taken for interrogation. The mission is to get him out. Get him out before he talks, before he starts singing like a canary. The only way to do this is with stealth and secrecy. And you gentlemen, Wymark adds with a flourish, are all stealthy and secretive. So stealthy and secretive that none of them betrays the slightest reaction to this rhetorical compliment.

The purpose of the mission is now clear—and how could it not be clear when it’s all being enunciated with such impeccable clarity? Essentially the briefing is a virtuoso display of syllabic carving, an elocution demo, and given that the film often reflects on what it’s up to it’s a shame that the word “enunciate”— couldn’t the mission be code-named Operation Enunciate?—is not itself enunciated in the course of this briefing, in which Eastwood (Lieutenant Schaffer) is entirely silent even when he’s introduced to the others, so although he might be taken as a representative of the new American style of nontheatrical acting he’s also a leftover from the silent-movie era.

All of you, Colonel Turner continues, besides being fluent in German, are expert at survival “behind enemy lines”—a three-word phrase which has never lost its appeal, which still describes the allure and glamor of the special forces, and which exerted such a hold on my childhood that it sometimes seemed that the purpose of enemy lines was primarily to afford small teams of highly trained soldiers the chance to go on acting missions and utter their lines behind them.

A subset of soldiers who find themselves behind enemy lines are POWs who want to break out of prison, ostensibly to get back to Blighty, in front of enemy lines, but also in order to behave like real soldiers behind enemy lines: darting around, evading capture and generally making a nuisance of themselves (Steve McQueen and his motorcycle most spectacularly, in The Great Escape), though none will cause as much of a nuisance as this seven-man team, one of whom now feels compelled to enquire—presumably as a representative of potential audience skepticism about the planned mission—why they don’t just send in a Pathfinder squadron of Lancasters and blow the Schloss to kingdom come?[2]

Because, replies Michael Hordern (Admiral Rolland), clearly determined not to be out-enunciated by Patrick Wymark, the prisoner, General Carnaby, is one of the architects of the Second Front and blowing up the Schloss would involve blowing him up too, thereby threatening the UK-US alliance on which the fate of the world depends. Which means, more immediately, that the fellow who asked the question can only sit there like a kid in a history class who’s been given a rap over the knuckles by a teacher whose dedication to the annual production of the school play is a matter of proven record.

So that’s it, they’ve got to get in and get Carnaby out, before he spills the beans on the Second Front. Over and above this possibly impossible mission the larger importance of special operations has been emphatically affirmed. This is in keeping with the way that the role of the Special Operations Executive was “puffed by a powerful lobby of historians, some of whom were its former officers.” The truth, John Keegan continues, is that the SOE “largely fails in its claim to have contributed significantly to Hitler’s defeat.” It all depends, I suppose, on what is meant by truth. Isn’t it true, for example, that when Max Hastings summarizes the hopes of Operation Biting—a 1942 plan to capture Luftwaffe night-fighter radar systems from Bruneval on the coast of northern France—in his book The Secret War, he does so in terms that echo Wymark’s? “Surely it should be possible for a daring raiding party to get in—then, more important, out, having secured priceless booty.”[3]

There might be love interest but there’s no love time.

Operation Crossbow, The Guns of Navarone, Cockleshell Heroes, The Heroes of Telemark and The Rat Patrol enacted the (repeatedly heroic and daring) truth of my boyish perspective on the war. That perspective has since been altered, corrected, radically changed, but nothing can erase it entirely—any more than an acknowledgement of the decisive importance of the Battle of Stalingrad can downgrade the formative role of the local Battle (of Britain) or the retreat from Dunkirk in my enduring interest in the Second World War.[4]

And if director Brian G. Hutton cannot comfortably sit alongside auteurs such as Tarkovsky, Herzog, Antonioni et al., Where Eagles Dare still seems, fifty years after its first release, to contain some essence of what cinema means to me now, when action movies have become a form of explosive torpor. “Every onlooker who fancies his powers of discrimination has a wonderful time when a blockbuster flops on the opening weekend,” writes Clive James in Cultural Amnesia:

But the blockbuster that we actually have a wonderful time watching is a more equivocal case. Where Eagles Dare has always been my favorite example: since the day I first saw it, I have taken a sour delight in rebutting pundits who so blithely assume that the obtuseness onscreen merely reflects the stunted mentalities behind the camera, and I go on seeing its every rerun on television in order to reinforce my stock of telling detail—and, all right, in order to have a wonderful time.

It’s not just that I’d rather watch Where Eagles Dare than Wim Wenders’s Until the End of the World because it’s more fun; I’d rather watch Where Eagles Dare because it’s better than Until the End of the World—but then, what could be worse?

Before we’ve had a chance adequately to reflect on such matters—or on the preponderance of Ws in the preceding sentence—we’re back in the plane, which is now over the drop zone. (Since the drop zone is almost always behind enemy lines it serves as a vertically concentrated essence of the horizontal expanse of generalized danger evoked by the latter term.) They’re clipping their parachutes to the static line, the red light is flashing green, and they’re tumbling out of the door. First out are the beer barrels, as if the whole mission is really a pretext for a behind-the-lines keg party, except we can see now that they’re actually canisters of equipment, bigger and longer than kegs but surprisingly small given the scale of the mayhem their contents will inflict on the host nation. Last out, several seconds after the last of the seven-man stick—and unseen by them—is a woman.

Landing in cushioning snow and trees, the silver canisters have the quality of seasonal hampers stuffed full of guns, explosives and other weaponry—exactly what we wanted for Christmas as kids. After the hamper-canisters come the men, their mushroom canopies drifting slowly and softly over the soft and silent snow in which they land softly and safely, silently and whitely, discreetly, very whitely. It’s so idyllically wintery it could be a scene on a Christmas card from jump school. They’re behind enemy lines, but there’s not an enemy in sight (because the enemy is even deeper behind enemy lines than they are?). One member of the team is missing and they spread out to look for him, trudging through the knee-deep snow, all wearing their snow-patrol parkas and over-trousers.[5]

It doesn’t take long to find the missing man. “Major!” bellows one of the search team, loudly disregarding what might reasonably be assumed is the first rule of stealthy survival behind enemy lines. The missing man is no longer a missing man; he’s a dead man. His neck’s broken (the snow is not as soft as it seemed), so now there are just six of them. It’s a bad start, possibly an ill omen, but missions behind enemy lines have a habit of going wrong: the Black Hawk shot down over the Mog, the attempted rescue of the hostages in Iran that put paid to Jimmy Carter’s presidency, the helicopter crash that jeopardized the mission to whack Bin Laden, the discovery of the sniper team by Afghan shepherds in Lone Survivor . . .

In combat anything that can go wrong will go wrong—at the worst possible moment, before the combat, properly speaking, has even begun in this fictive instance. So Burton (Major Smith) doesn’t waste time crying over spilt milk—he tells the rest of them to continue unpacking the hampers while he tests the dead man’s radio. Makes sense—though as soon as they’ve trudged off he becomes more interested in the dead man’s address book or notebook, which isn’t necessarily so weird since it contains much-needed call signals; but the music has turned a little spooky, positively Hitchcockian.

There’s more to this mission than meets the eye—which becomes more apparent when they get to the cosy, conveniently located Alpine barn and are shuffling off their snowsuits and changing into their German uniforms. This just isn’t me, says one of the team, a guy whose name, whether his actual name or that of his character, we haven’t even bothered learning, so that we don’t know or care whether “this” (the uniform) is “me” (him) or anyone else (not him). Burton announces that he can’t use the radio because he’s left behind the codebook which we’ve seen him tuck into his own tunic just a few minutes earlier, when they were out in the cold snow, before they got to the cosy cabin.

To retrieve the notebook that doesn’t need retrieving he trudges out into a blizzard that doesn’t look like much of a blizzard, but he only goes round the corner to a neighboring hut where, rather conveniently, Mary Ure—last seen jumping out of the plane—is waiting in her winter-espionage wardrobe. Without so much as a by-your-leave Burton rummages through her luggage, where he discovers some undercover, lacy underwear, which he holds up admiringly, though to 21st-century eyes they seem like bloomers.

So far Burton has done nothing but give orders, so this is an important exchange in that he might reveal another side of his character. This side of his character also involves giving lengthy and complicated orders about what to do and where to go, but for Ure it’s a definite improvement on getting her head snapped off every time she opened her mouth—or didn’t open it—when they played opposite each other as Jimmy and Alison Porter in Look Back in Anger ten years earlier. He doesn’t even raise his voice while putting her straight after she says she has a right to know what’s going on. And he does offer up a useful bit of intel, namely that the radio operator didn’t die accidentally in the drop: he was killed, his neck broken after he’d been knocked out.

So now, in addition to intrigue (what’s Ure doing here?) and mystery (why was the radio operator killed and by whom?), there’s also suspense. And love interest (Ure again), which is usually conspicuously absent from MacLean’s books. There might be love interest but there’s no love time, so after a quick filmic snog—which might stand in for a roll in the hay, of which there is plenty in this annex to the main cabin—Burton is on his way out and heading back to the lavishly appointed (relatively speaking) boys’ dorm where they’re all sleeping.

Except for Eastwood, who’s walking around in his German uniform as though he’s still up late at one of those fancy-dress parties that get members of the royal family in trouble because they haven’t twigged that there’s more to wearing a German uniform than wearing a German uniform, a fact cleverly or stupidly exploited by the Polish artist Piotr Uklański in his 1998 work The Nazis, featuring 164 stills or posters of actors playing the parts of German soldiers (not Nazis necessarily), including Eastwood in his current role of Lieutenant Schaffer, even though, strictly speaking, he’s neither a Nazi nor a German soldier but an American Ranger on his first night out with his new English pals who, for all he knows, are no strangers to this kind of politically questionable costume romp.

Squinting is pretty much the limit of Eastwood’s facial range as an actor.

There’s a bit of snoring in the cabin, but Eastwood is too alert—in a relaxed sort of way—to sleep, so he’s waited up for Burton like the concerned parent of a teenage son out on a date on a snowy New Year’s Eve. Checking his watch in a checking-but-not-overly-anxious way, he kills time cleaning and disassembling his Schmeisser submachine gun. The idiom is no accident. His relationship with time— killing it—accurately anticipates what will turn out to be a homicidal relationship with almost everyone he encounters outside this little cabin. When Burton comes back in with an implausible story about meeting a stunning blonde in a snowstorm Clint squints at him suspiciously, quizzically, Eastwoodly, all the time applying lube to his Schmeisser, as if he knows the Major has been up to something, especially when Burton—having gone to the trouble of retrieving the codebook from a dead body in the dead of night in the midst of a notional blizzard—gives up trying to contact London after a few seconds and says it can wait till the morning.

There was a slight redundancy in the preceding sentence when I said that Clint squints at Burton. Squinting is pretty much the limit of Eastwood’s facial range as an actor. Eastwood has basically squinted his way through five decades of superstardom, squinting in a variety of outfits (poncho and tweed jacket, most famously) and in response to a variety of stimuli (guns, chicks, gags; danger, love, humor) in a way that renders him, in facial terms, monosyllabic. Or duosyllabic, since the squint crops up with such regularity as to become the default setting of the Eastwood face, so that not-squinting—expressing nothing—becomes expressive of the entire range of human emotions that exist beyond the limits of the squint.

In this regard he faces, so to speak, stiff competition from numerous American actors from the 1970s, all vying with each other to see who can do most with least—or least with less. David Thomson admiringly evokes “the sculptured Lithuanian rock” of Charles Bronson’s face as he dispensed “monumental violence, always with an expression of geological impassivity.” And whereas the face is usually the main way of identifying a person, in Point Blank the face of Lee Marvin (Walker) gives nothing away; it’s the way he walks that establishes who he is (which is ontologically synonymous with what he does; he is he who walks).

But in terms of the non-manifestation of whatever is going on inside—or, possibly, the clear manifestation of an interior nothingness—Steve McQueen was the master. By comparison with McQueen, Eastwood was the Jim Carrey of his day, a virtuoso gymnast of the visage. I said that Marvin gave nothing away; McQueen does—and gives away—less than nothing. Hence the beautiful redundancy or double negative of his role in The Cincinnati Kid, in which he has to enact an ideal of the poker-faced poker player.

But it’s in Bullitt that he took things (logically, the opposite of giving) to another level, even if the nature of that level is, by definition, impossible to discern. In Bullitt McQueen’s face takes us into a kind of submarine world whereby the oceanic depths of impassivity suggest the dense topography of the Mariana Trench with all the dead weight of multiple atmospheric pressures bearing down on it and him; a case, perhaps, of what Thomas Bernhard calls “exaggerated understatement.” It helps that McQueen’s face has no distinguishing features apart from the eyes; Eastwood is strikingly handsome, gorgeous, but he has that essential ability—especially important when playing the part of a cowboy or gunslinger—to be seen to be gazing into the middle distance even when doing up-close work such as obsessively lubing his Schmeisser. So when he looks up across the table at Burton it’s as if he’s gazing clear across the horizon, through a blizzard of radio static, into the Welsh valleys of his costar’s troubled, booze-addled psyche.

[1] By the time I was twelve the idea of the impregnable had been so thoroughly impregnated by notions of pregnability that to describe a place as impregnable was to suggest its extreme vulnerability to infiltration and attack.

[2] The Avro Lancaster was my second-favorite—and the second-most-complex—Airfix model aircraft after the American B-17 “Flying Fortress.”

[3] The comparison is helped by the way that the “Bruneval raid was the most successful such operation of the war.”

[4] Christopher Nolan’s Dunkirk was an overwhelming experience, partly because I saw it on IMAX, as Nolan intended. But also—and perhaps this too was intentional—because it was like witnessing a dramatized, massively enhanced projection of some of the components of the national culture that had formed me and my contemporaries. The film was designed to be immersive; what it immersed me in—symbolically expressed by the Spitfire gliding silently onto the beach where the stuff of consciousness yields to and is cushioned by the claims of the unconscious—was the experience of seeing what was already there, waiting for the film as it landed in my head.

[5] One of the most prized items in my Action Man’s ward- robe was his ski patrol outfit. I remember it vividly—the green goggles, the oven-glove white mittens that rendered the white rifle unholdable—because my parents bought it for me on an inappropriately sunny day when I had a tooth pulled at the dentist’s. On the way home my mum told me off for spitting blood onto the pavement and gave me a handkerchief to spit into. Later she took a picture of my dad and me in our garden, in the sun with our shirts off, while Action Man toiled away conspicuously on the grey grass of the lawn in his white parka and skis like some totemic warning about the looming catastrophe of climate change. That was the nearest we ever got to a skiing holiday.

__________________________________

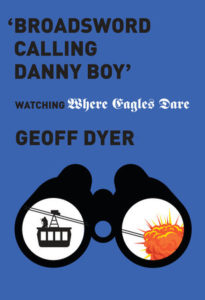

Excerpted from Broadsword Calling Danny Boy by Geoff Dyer. Copyright © 2019 by Geoff Dyer. Excerpted by permission of Pantheon Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Geoff Dyer

Geoff Dyer’s many books include The Ongoing Moment (winner of the International Center of Photography’s prestigious Infinity Award for Writing/Criticism), But Beautiful (winner of the Somerset Maugham Prize), Out of Sheer Rage (shortlisted for a National Book Critics Circle Award), The Missing of the Somme, the novel Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi, and the essay collection Otherwise Known as the Human Condition (winner of a National Book Critics Circle Award). His latest book is White Sands: Experiences from the Outside World. A recipient of a Lannan Literary Fellowship, the E. M. Forster Prize and, most recently, the Windham-Campbell Prize for nonfiction, Dyer is an honorary fellow of Corpus Christi College, Oxford; a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature; and a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. His books have been translated into 24 languages. Dyer is currently writer-in-residence at the University of Southern California.