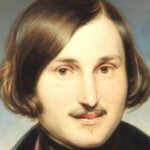

Gabriel Byrne Talks Memory, Loneliness and More With Karl Geary

In Conversation About Byrne's Memoir Walking with Ghosts

This is part of an ongoing conversation, Gabriel and I have been having, in various coffeeshops, in various parts of the world. Today, we two near-luddites find ourselves on Zoom, in Maine and Glasgow respectively.

*

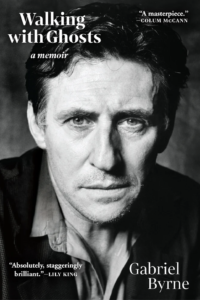

Karl Geary: I thought I’d start by just embarrassing you a little bit. I was just looking through some of the notices Walking with Ghosts has received. The first one that struck me was from Edna O’Brien, who says, “The wonder of this memoir is its unembellished truth. It’s written by a man whose amazing story is the stuff of literature,” and then Colm Toibin: “Dreamy, lyrical and utterly unvarnished.” Colum McCann comes in and says, “Make no mistake about It: This is a masterpiece.” I mean, that’s three pillars of Irish literature. And all have said that you’ve managed to do something with the memoir that hasn’t been seen before in Irish literature. It’s an enormous achievement. You’re somebody who could do a number of things. You’d already written a book 20 odd years ago, you knew the difficulties. What was it, do you think, that made you want to attempt this massive undertaking?

Gabriel Byrne: Yeah, well, I would agree with you there, Karl. I mean, in terms of it being a massive undertaking, I think that if I can compare it for a moment to, say, preparing a role for the stage or for film, the initial excitement soon gives way to the fact that that’s all it is, an initial excitement. And then the hard work of actually putting everything together begins. And that involves, in my case, anyway, always a lot of missteps and miscalculations and over-optimistic forays into what are often cul-de-sacs. And the final thing eludes you completely.

What I did know was that I didn’t want to do a conventional thing. I mean, there wouldn’t be any reason for me to do that. But in thinking about it, what I decided to do, I think, was not a chronological book, but to think to myself, what were the moments in my life that changed me forever? What was the first time you became aware of time? Even if you couldn’t make head or tail of it, but the notion of it started to infringe on the edges of consciousness. What was the first time you became aware of death? What were the first flickering images of childhood, the first recognitions of some kind of reality? What was the first time you were introduced to the notion of love and sex? You know, the first misunderstood and incomprehensible yearnings and longings for romance and love? All those invisible markers in the journey. When were they? So, it was a series of firsts.

KG: Something I found remarkable, Gabriel, is how you choose to distribute value or significance. I suppose when we think of the typical actor’s memoir, we assume the great importance is going to be placed at what is perceived as glamorous, you know, and that’s not the way you’ve approached it at all. Equal value is given to moments of isolation, on the moments where you aren’t on the world stage or on any stage. And actually, the book is shrouded with a sense of isolation, separateness. And I wondered if there was anything in that, is this a necessary isolation in order to be able to filter the information that’s coming in and reinterpret it as art? Is some degree of separation or otherness necessary in order to be able to reflect and retell a story?

GB: I think that’s possibly true for a great many artists. I always remember that image of Joyce writing Ulysses in Trieste, on the back of a suitcase and Nora sweeping under him, saying, “you lift up your legs Jim.” I don’t know why that image stays in my head. [Laughs] You know, isolation, distance, are those things necessary to write? I mean, I’ve always written in cafes because I can’t bear the idea of sitting in a room, looking at a wall. It reminds me too much of school. I want to be out among people. But what’s interesting there is you talk about isolation and loneliness. I think that we’re all isolated in our own particular ways. And I think one of the things that writing does, or reading or being exposed to art, it makes us feel less isolated and it makes us feel connected to the world.

In the book, I do acknowledge the fact that I have experienced loneliness in varying degrees, the loneliness of being out of step sometimes with everybody else and not feeling that I had anything in common, that I was other than, not in that Byronic haughty way, but just that I never felt that I fit it in. I don’t know where that came from. I don’t know if that’s something that’s common to a great many people who express themselves artistically.

I think that we’re all isolated in our own particular ways. And I think one of the things that writing does, or reading or being exposed to art, it makes us feel less isolated and it makes us feel connected to the world.KG: Something we’ve talked about before, is this notion of memory, it’s reliability. That as soon as we have the memory, we’ve rewritten it, it’s forever changed. And you had brought up William Maxwell. He says, “In talking about the past, we lie with every breath we draw.”

GB: In relation to Maxwell, I think what he was saying is that there’s a very thin line between memory and imagination and that a novelist, as you well know, imagines the world. And I think somebody who’s writing a memoir is involved in the excavation of fact, revealing some kind of truth. But how dependable is that fact? I think that in terms of memoir, the unadorned fact is just a newspaper column. What you have to do is to try to use the imagination in a way—not to be untruthfully in the moment—but to see how you can add to the truth of this by adding in details and call on that sensual world, not to be dishonest, but to say, “how can I actually convey this thing here that will make people understand that moment of unadorned fact?” Does that make sense?

KG: Yes, it does. It absolutely makes sense.

GB: And maybe you can answer this question? Fundamentally, if you’re writing a memoir as opposed to a novel, the memoir is bound in by the walls of what happened. But as a novelist, you’re not restricted by factual truth. You are restricted by a certain truth, of course, because you want to make the novel as truthful as possible. How free do you feel starting a novel knowing that your canvas is totally blank and free? Is that frightening or is that liberating?

KG: I think for any writer, the blank page is terrifying. It’s an interesting journey, because like writing a memoir, as soon as you take a step in any direction, you’ve locked into something. And I think that’s worth trying to resist, particularly early on, locking in too strictly. If you’re writing from a character base, you have to allow enough room to listen to that character and allow them to navigate. So, you’re always listening to someone’s voice, be your own, or fictional.

You’re a very private person and there’s a great honesty in your book, in talking about alcoholism, the death of your sister, and about abuse. Certainly, in Ireland, there is this sense, you know, that we’ve had this conversation, it’s happened. It’s time to move on, even though the institutions involved have been allowed to continue without any real repercussions. It feels to me like you’ve readdressed it here and you’ve allowed for the beginning of what could be a new conversation. How difficult was it for you to make that decision? Is there any way to resolve these things or do we just make do with finding whatever comfort in the attempt to resolve them?

GB: Well, I don’t think writing about something brings resolution. I think there’s an idea, which I don’t subscribe to, a kind of a modern cultural idea that you face the problem, you find closure and you move on. But I wanted to talk about it from the point of view of something that I’d never seen before. How an authority figure, who was perceived at that time to be beyond authority, a direct line to God. So, when somebody like that told you something you believed without question. How does a man, who understands how innocent a child is, how does he go about seducing that child through language? I wanted people to understand how impressionable the child is. He was using the rituals of Catholicism to give himself cover. I’ve never seen that put down before.

And to your point, can you resolve this? I think when I found him, you know, in this retirement home and I can’t tell you how nerve wracking it was to hear somebody saying, yes, he’s here, and the phone clattering down on the desk and footsteps and a door opening with a squeak and then silence and then the footsteps coming back and the phone being lifted. And here I was in contact with this man that I had thought about for a very, very long time. And what shocked me, first of all, was that his voice was as gentle and as kind as it was. That really hit me hard. Here I was, a 40- or 50-year-old man, I could succumb to the kindness in his voice instantly, what chance had I got at 11 years of age? And so, was there a resolution involved? No, there was no resolution. What you have to accept is that sometimes there is no resolution. That’s OK. And that’s something that I now have to deal with. And whether I move on or find closure? I’ll never be able to say with certainty that that’s the case because it will always be part of my memory.

KG: There was something I was thinking about actually, in terms of resolve. There is that Susan Sontag quote, “A landscape of devastation is still a landscape, there’s beauty in ruins.” The idea has been that, even if your inner life at some point has been made desolate, something will grow over the rocks and the concrete, awareness continues. And maybe that’s all we get, you know, as scarred or as broken as a landscape is, our perspective can shift. And maybe that just has to be enough.

GB: I agree. I think that one of the causes of discontent is expectation, the expectation that we are entitled to something. The reality is the ruins. And the ruins are really an intermediate stage between oblivion and growth. So this idea that desire and expectation produced somewhere along the line, some kind of happiness or contentment is also a little bit, from my point of view, a little bit delusional. The reality of life is that we’re all in ruins on the way to obsolescence. And I think the biggest battle I have is accepting reality as it is.

KG: I wanted to ask, presumably you had some sort of a ritual for yourself when you were writing and now that this particular book is finished and completed, do you miss that ritual? Do you find yourself moving back towards it? Do you miss writing?

GB: My admiration for people who sit down every day at a desk and do their four or five hours is enormous, especially given what you’re saying about the terror of looking at a blank page. It’s like saying, do you miss the rigors and the embarrassment and the little joys of it. No, I don’t. I don’t miss the rigors of writing because I don’t enjoy it that much, but I don’t enjoy rehearsal that much either. It reminds me so much of school and university, it should have been pleasurable, but wasn’t. How do you feel about that?

KG: I hate it. I hate it. But I hate it less than I hate anything else. I heard somebody say recently that the worst thing about being a writer is that you always have homework, it’s always Sunday night and it will never get done.

The idea has been that, even if your inner life at some point has been made desolate, something will grow over the rocks and the concrete, awareness continues.GB: And it’s a bit like learning lines, and you start getting these dreams of being on the set and somebody saying, OK, you’ve got to say those two pages now. And you don’t know them. It’s a classic anxiety dream for actors and performers. And I’m sure that there’s a version of that for writers. The idea of guilt and not writing is an interesting one, too. Yeah. Why do you feel guilty? Because you haven’t completed a page?

KG: I mean, honestly, I think once you’ve formed whatever this relationship is with these characters, you’re sort of become their guardian in some way and you owe them some debt that is repaid by telling their story in full. And it becomes very tangible, you know? But I think that title, “Novelist.” I found that very difficult to commit to, because it’s almost too grand a statement.

GB: Yes, but that’s interesting too. I would hesitate to call myself a writer, but what I’ve done is written. And that gradual thing that you are talking about, I can feel that beginning to take hold. I don’t want to sit down in front of the desk. I don’t want to have to do all that stuff. But, some kind of an instinct is saying to me, do it.

KG: In some ways, as your early life was in academia. You had studied Irish, you were teaching, you were in that universe and then the trajectory of your life suddenly shot out in another direction. I wonder, in an alternate universe, do you think you would have committed your younger self to that life?

GB: Well, that’s a great question, because that’s probably about the road not taken. There is this idea of a mentor or somebody who encourages you because they see in you something that they feel you should develop. I mean, I often ask myself that question: have I ever had somebody like that in my life? What a wonderful thing that would have been. But there was nobody that you could confide in because your ambitions and your desires were not legitimate. I still have a kind of a vestige of that left over—a tendency to believe criticism more than I believe praise.

KG: I want to ask about your title, Walking with Ghosts. There’s this idea, from the earliest campfires, ghost as a type of receptor, where the individual or society could lock their fears away. This idea, coupled with the notion of walking, of movement. We are tempered by that nomadic existence, by the people you interact with. And your life has been may things, but essentially, it’s been an immigrant’s journey. I mean, are these things you thought about with the title of the book?

I still have a kind of a vestige of that left over—a tendency to believe criticism more than I believe praise.GB: Many years ago, I did a famine walk to commemorate the people who were walking to the workhouse, basically to die during the famine. And the walk was led by an American Indian from the Choctaw Nation. Before we started, he said, look, we have a tradition in our tribe that when we walk, the ghosts of our ancestors walk with us. They’re always walking with us. And then to your point about going home, one of the reasons I find a kind of a contentment about living in Maine, is that it’s a blank slate. When I go back to Dublin, every doorway, every pub, every cinema, they’re filled with ghosts.

And the reality is that as an immigrant you become in your own way a kind of a ghost, because people don’t see you in the same way. They see you as a kind of a specter from somewhere else. And it’s something that’s recognized in mythology and religion, which is, in my opinion, a form of mythology, the idea of a permanent home, which is heaven. We’re on our way home to heaven. There’s even a hymn. “And here we are, poor, banished children of the exiles.” You know, the human race is actually called exiles. But you are a ghost when you come back to confront the past. You know, so it was the idea of walking with the memories and the voices and the experiences of the people who have gone before us, as one day our children will come.

__________________________________

Walking with Ghosts by Gabriel Byrne is available now via Grove Press.