FYI: There’s probably a club-footed Frenchman in Yeats’ grave.

W. B. Yeats, the hopelessly romantic, doggedly priapic, Nobel Prize-winning Irish poet and dramatist, died in the Hôtel Idéal Séjour, in the French Rivera town of Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, on this day in 1939.

As I wrote a while back, even if you’re someone who avoids poetry like the plague (shame on you, but also, fair), there’s really no escaping Yeats’ appearances in contemporary popular culture. If you’ve watched The Leftovers or The Sopranos or Buffy or Wall Street or The Bridges of Madison County, read Joan Didion or Chinua Achebe or Cormac McCarty, listened to Joni Mitchell or Lou Reed or The Waterboys or Joe Biden addressing a group of Irish/Irish Americans/himself in the mirror, well, you’ve probably been exposed to at least a line or two by the deep-feeling Hibernian bard.

You may have also heard that Yeats penned his own epitaph and inserted it into a poem—”Under Ben Bulben“—about, among other things, his (expected) final resting place in County Sligo. (“Under bare Ben Bulben’s head / In Drumcliff churchyard Yeats is laid.”)

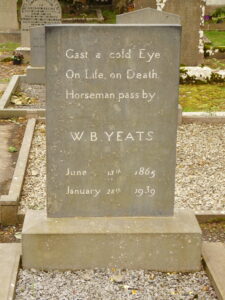

Yeats’ grave is one of the most visited in Ireland, with up to 80,000 people making the pilgrimage to Drumcliffe graveyard every year to read that iconic tombstone inscription (“Cast a cold eye / On life, on death. / Horsemen pass by”) and pay their respects to . . . a club-footed Frenchman. Or perhaps several of them.

Yes, this is your annual reminder that it is highly unlikely the bones buried underneath this very cool tombstone are those of W. B. Yeats.

“If I die, bury me up there [in the churchyard at Roquebrune] and then in a year’s time when the newspapers have forgotten me, dig me up and plant me in Sligo,” Yeats told his wife George back in the late 30s when he suspected the end was nigh. The outbreak of WWII prevented George from carrying out her late husband’s request and for the next few years Yeats slept peacefully in Roquebrune soil as the bombs fell and the bullets flew across Europe.

Then, in June of 1947, Yeats’ last lover, the journalist Edith Shackleton Heald, and her lover Hannah Gluckstein, the painter known as Gluck, decided to pay a visit to the poet’s tomb, only to learn from the local curate that Yeats had been disinterred the previous year, and his bones mixed with others in the ossuary. This was, understandably, pretty upsetting news for all concerned.

What followed was a somewhat cack-handed, though reasonably successful, conspiracy (which you can read about in detail here) involving a local pathologist, a number of French (and probably Irish) diplomats, certain member of the Yeats family, and god knows how many bemused gravediggers and customs officials, whereby an assemblage of bones from various unknowns would be passed of as the complete skeleton of the 1923 Nobel laureate in order to prevent an international incident.

For the most part, this sham repatriation was a success, though word of Heald and Gluck’s macabre discovery had reached the ears of some of Yeats’ contemporaries by the time his new coffin reached Sligo.

As Lara Marlowe wrote in the The Irish Times back in 2015 (the year a cache of secret French documents all-but confirming the ruse were made public):

At the ceremony in Co Sligo the poet Louis MacNeice protested that the shiny new coffin transported by the Naval Service was more likely to contain “a Frenchman with a club foot.”

Now, unless Yeats’ descendants submit to a comprehensive DNA analysis of the bones in question, we’re unlikely to ever know for sure if any of the poet is actually buried in his grave, but I suppose at this point it doesn’t really matter.

As a wise man once said, “shrines are about stones, not bones.”