Fukushima During Coronavirus: Life in Double Isolation

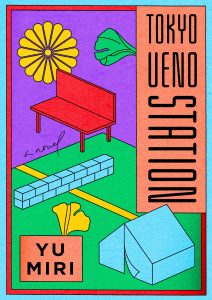

Yu Miri's View From the Railways of Japan

Translated by Morgan Giles

When you hear the words “Japanese trains,” what do you imagine it’s like to ride on one?

I’d guess that what you’ve seen on the news in your country most often is the Yamanote Line trains, which run in central Tokyo. The Yamanote is a loop line. It has 29 stations over 21.4 miles; you can do a full loop in 60 minutes. On average, 4,540,000 people use it per day. During morning rush hour on weekdays there’s a train every two minutes. It operates at 150-160 percent of capacity. You’re lucky if you can grab a handrail or a strap; most people have no choice but to brace their legs and try to withstand the movements of the train. You’d struggle to get on wearing a backpack, and looking at your phone is impossible. Some men apparently are so conscious of the possibility of being mistaken for gropers if their bodies or hands get pressed up against women that they try to keep their hands in the air as much as they can when on the train.

Tokyo Ueno Station, which is being published in America this month, is the fifth work in my “Yamanote Line series.” The theme at the core of this series is suicide, to which over 20,000 Japanese people lose their lives every year. I’ve depicted the directionless lives and deaths of characters whose diverse lives radiate out from the ticket gates of Yamanote Line stations, who get knocked out of life and, passing through the gates heading toward the center of the circle, find themselves standing on a precipice—the edge of the station platform.

On April 7, the Japanese government declared a state of emergency due to the novel coronavirus outbreak in all urban areas, including Tokyo. On television and online, all the reports said that rider numbers on the Yamanote Line were down 85 percent compared to the same period in the previous year. But I don’t ride the Yamanote Line.

After the lifting of the emergency order on May 25, the number of riders on Tokyo’s most used train line has returned to about half of what it was the previous year, but I’m far from Tokyo, and I don’t know the facts.

I live in a town called Odaka, part of Minami-Sо̄ma, in Fukushima Prefecture. Odaka is in the former “exclusion zone,” located about 10 miles north of the Fukushima Dai-Ichi Nuclear Plant where a level 7 accident occurred on March 11, 2011; because of the nuclear accident, the population once fell to zero. The evacuation order was lifted on July 12, 2016, but only 3,663 inhabitants have returned (there were 12,842 before the nuclear accident).

I run a bookstore called Full House in part of my own home, about two minutes’ walk from Odaka Station, which is on the Jо̄ban Line. I wanted to create a safe place where high school students who miss the train can wait for the next one and have a snack, read books, do their homework, play games or look at social media on their phones, so I decided to build a book cafe.

“We are struggling to bring in supplies, and we’re asking for your support.”

The Jо̄ban Line, quite unlike the Yamanote Line which runs through the center of Tokyo, runs only once every hour or two. Odaka Station is hardly bustling, like it once was. Thanks to the nuclear accident, most shops and restaurants are gone.

A lot of the stations and tracks on the Jо̄ban Line were washed away by the 2011 tsunami. And due to the dispersal of radioactive material, many station buildings had to be rebuilt and tracks had to be decontaminated in high-dose areas.

After the nine years it took to complete this construction and decontamination work, the entire line was finally reopened on March 14 this year. That day, one to be commemorated, I got the Jо̄ban Line express train. Now, I could go from Tokyo Station to Minami-Sо̄ma in 3 hours and 27 minutes without a transfer.

As I recited, one after another, the names of the stations in the area near the nuclear reactor where service had been suspended, the pain that the inhabitants of this land had gone through to see this day came to me, and I couldn’t hold back my tears.

I reopened my book cafe Full House on March 20 after renovations, to coincide with the resumption of service on the Jо̄ban Line. When it originally opened in April 2018, it operated solely as a bookstore, with no cafe space.

But the return to full service on the Jо̄ban Line and the reopening of Full House had the worst timing.

The coronavirus.

On April 16, the declaration of a state of emergency was expanded to apply to the entire nation, and the road to the station where my store is, which had always been light on foot traffic, was now completely dead.

From April 28 to May 19, we closed Full House. Since May 20 we have been reopen for business, except for the cafe.

*

Minami-Sо̄ma had, nine years earlier, experienced something close to lockdown.

In those days, the people here faced a crisis during which food, gasoline, and relief supplies could not reach the city at all because shipping companies, fearing exposure to radiation, refused to bring in goods.

The Jо̄ban Line, the only railway connected to the area, had ceased operations due to the tsunami and nuclear accident; those who decided to flee in their own cars found that they couldn’t, because the gas stations didn’t have any gas. Even the gas needed to cremate the 1,605 bodies of those who had died after being swallowed by the tsunami had run out.

On March 24, 2011, the mayor of Minami-Sо̄ma, Katsunobu Sakurai, made a call for support on YouTube. “We are struggling to bring in supplies, and we’re asking for your support,” he said. “Supermarkets, any stores you could buy basic items for daily life, they’re all closed. All financial institutions are closed. The people of Minami-Sо̄ma are facing starvation tactics.”

The white Tyvek protective suits, N95 masks, goggles, shoe covers, and other personal protective equipment that the world’s medical professionals on the front line of the fight against the novel coronavirus are now wearing are all intimately familiar objects to the people of Minami-Sо̄ma, and have been since nine years ago. They wore them during brief visits to their homes in the exclusion zone, and those doing decommissioning work wear them as well.

Since the start of June, high schools in the area have reopened. The students have to wear masks on the train; they are not able to take them off in class, either.

But today’s high-schoolers were kids when the nuclear accident happened—they’ve already known what it’s like to wear masks everywhere but their own homes to protect them from radiation.

Now, the exiled and returned of Fukushima find themselves cornered again by the pandemic.

Even now, nine years later, there are still vast areas of land deemed “difficult to return to” which are barred off to residents by gates, because the amount of radiation is so high.

More than 41,000 people are still living in effective exile due to the nuclear incident. And the deaths of 2,307 people from the physical and mental suffering, or from suicide out of desperation due to long years spent in temporary housing, have been designated as “disaster-related,” exceeding the 1,801 people who died or whose fate is still unknown due to the earthquake and tsunami.

Now, the exiled and returned of Fukushima find themselves cornered again by the pandemic.

The energy produced by the nuclear plants in Fukushima wasn’t used in Fukushima. It was all sent to sustain Tokyo’s abundance, to keep the Yamanote Line running every two minutes, to power all the neon signs that shine 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

This novel coronavirus has hit densely-populated Tokyo. Even the Tokyo Olympics, which were supposed to be held this summer, have been postponed. They’re now supposed to be held in the summer of 2021, but is that the truly just thing to do?

The people who live in Tokyo turn a blind eye to the misery in Fukushima which underpins all of Tokyo’s abundance, glitz and glamour.

Maybe this invisible virus is bringing all of the inequalities and injustices of this world out in the open.

I pray that when a silver bullet or a vaccine is discovered, that we won’t return to the old pre-corona normality, that somehow, there will remain loose threads to help us unravel and re-knit the world anew.

Morgan Giles is a Japanese translator and reviewer. She lives in London.

__________________________________

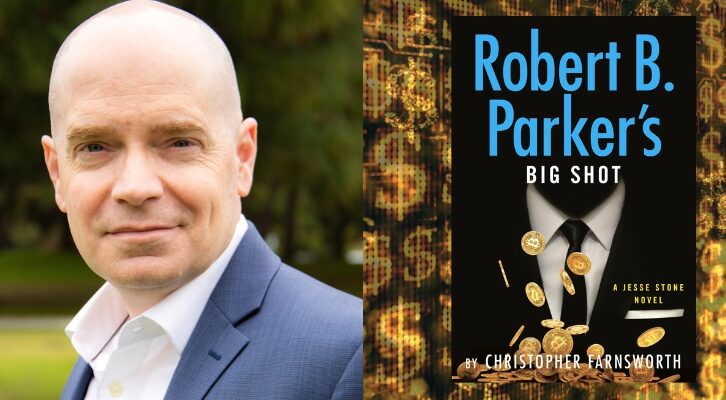

Tokyo Ueno Station by Yu Miri is available via Riverhead Books.

Yu Miri

Yu Miri is a writer of plays, prose fiction, and essays, with over twenty books to her name. She received Japan's most prestigious literary award, the Akutagawa, and her bestselling memoir was made into a movie. After the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Fukushima, she began to visit the affected area, hosting a radio show to listen to survivor's stories. She relocated to Fukushima in 2015 and has opened a bookstore and theatre space to continue her cultural work in collaboration with those affected by the disaster.