From Shakespeare to Tolkien, Treasures from the NYC Antiquarian Book Fair

Sarah Funke Butler Surveys Some Cool Old Stuff

A block-long drill hall mustering 200+ antiquarian book dealers from around the world can be daunting—55,000 square feet of back-to-back booths, ranging in feel from friendly book-shops to mini-museums, from tiny archeological digs to traveling houses of worship. What they have in common? A surfeit of important treasures and quirky delights, all testifying to the power of ink on paper.

The 59th New York Antiquarian Book Fair of the Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America (ABAA) and the International League of Antiquarian Booksellers (ILAB) opened last night at the Park Avenue Armory, and runs through Sunday. Below is a sampling of items sure to surprise, intrigue and impress—just a few of thousands.

To begin at the beginning: If you’ve been pining for a Gutenberg Bible, this weekend you can console yourself with the next best thing: Catholicon by Johannes Balbus, the second of three printings executed in Mainz by Gutenberg’s protégé Peter Schoeffer, ca. 1469 ($600,000.; Liber Antiquus, Chevy Chase, MD).

Catholicon—a 13th-century Latin dictionary used for Biblical interpretation—was one of the first books printed using Gutenberg’s recently invented movable type, and this volume showcases Gutenberg’s “other great innovation”—the casting of type in line-pairs. This is the second of three printings of the Catholicon, which boasts the first book to declare the city of printing, and the first to discuss the invention of movable type: “This excellent book, Catholicon . . . has been brought to completion . . . not by means of reed, stylus, or quill, but with the miraculous concurrence of punches and types cast in moulds . . .”

Once a book is printed, how it is collected, bound, read and preserved can inform our view of the text. This 17th-century DIY Assemblage of Shakespeare and his Contemporaries—including Hamlet, Othello, King Lear and Julius Caesar by the Bard, as well as 8 titles by other authors with whom you might be less familiar ($200,000; Maggs Bros., London)—is truly fascinating and a rare survival from this period. These plays, issued individually and selected and bound by their reader, are compiled into a volume offering us one version of Shakespeare’s evolving canon. There are very few data points this early, as most such volumes have been broken up and separately preserved or even reconfigured into different later anthologies. It is notable that in many of these plays women appear in the cast lists for the first time since their composition.

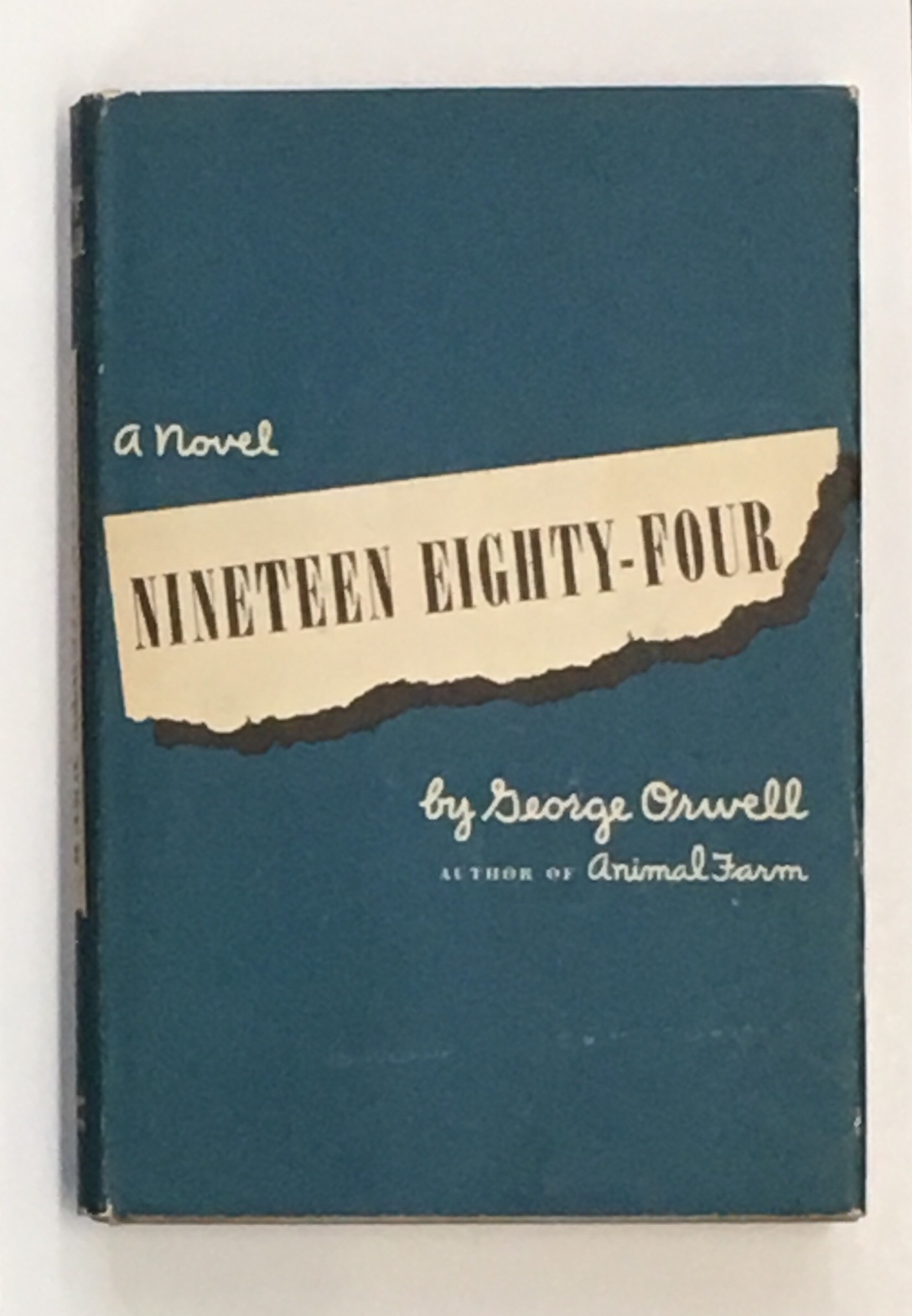

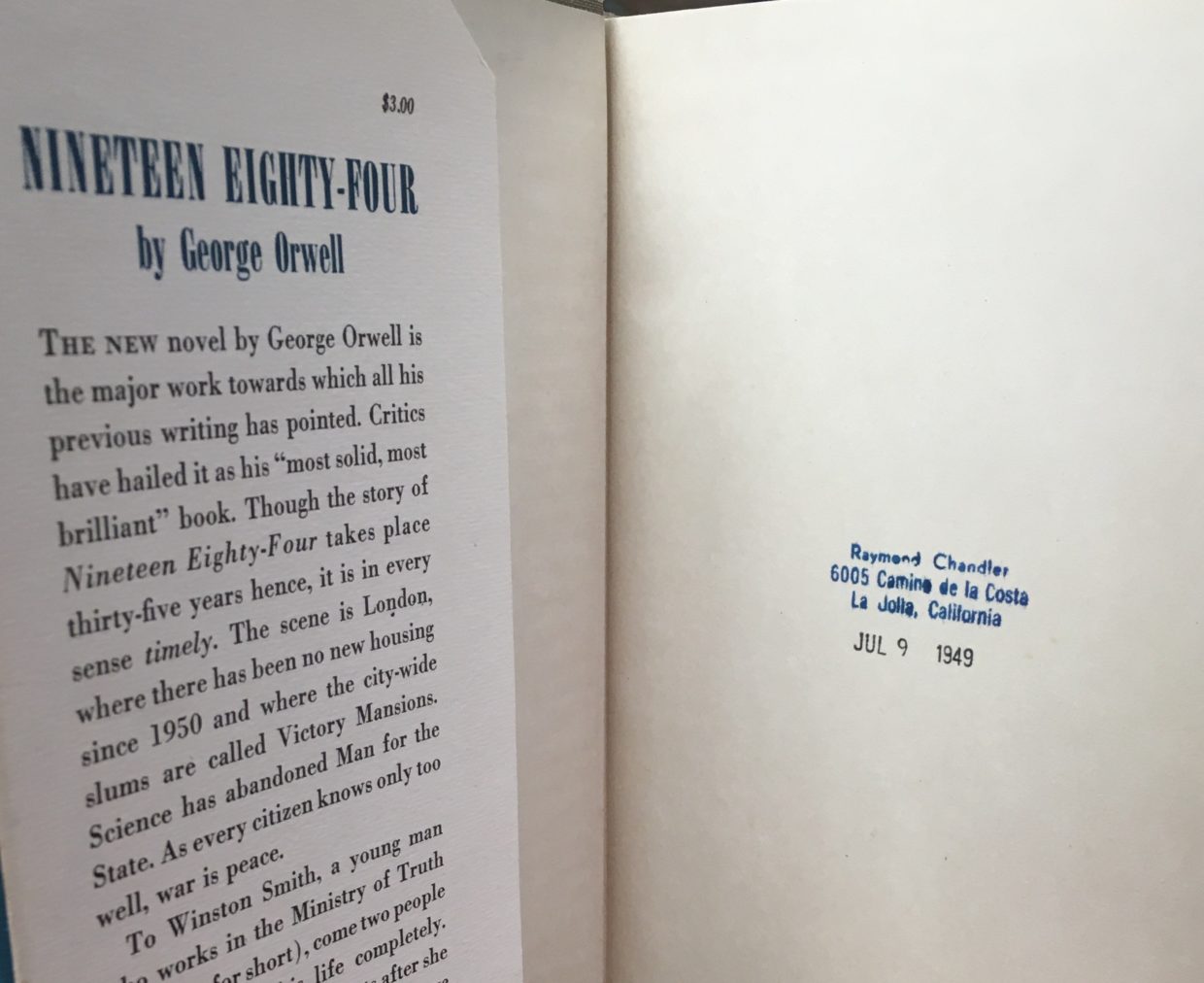

So-called “association copies”—volumes signed, inscribed, or annotated or from libraries—also show books in use, testifying to important relationships and intellectual engagement. One such volume is Raymond Chandler’s copy of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) ($6500; Honey & Wax Booksellers). This first American edition of Orwell’s dystopian masterpiece bears Chandler’s ownership stamp, “Raymond Chandler / 6005 Camino de la Costa / La Jolla, California” and, as was common with Chandler’s book, bears a date stamped in black beneath: “Jul 9 1949.” Chandler moved to the house on Camino de la Costa in La Jolla in 1946; it is there that he would write The Long Goodbye and Little Sister while under contract at Paramount as a screenwriter.

Chandler read 1984 almost immediately upon publication, telling his agent, Carl Brandt: “[I]f you were to consider Orwell’s 1984 purely as a piece of fiction you could not rate it very high. It has no magic, the scenes are only passably well handled, the characters have very little personality; in short it is no better written, artistically speaking, than a good solid English detective story. But the political thought is something else again and where he writes as a critic and interpreter of ideas rather than of people or emotions he is wonderful” (July 22, 1949). The same year Chandler read Nineteen Eighty-Four Orwell recorded reading The Little Sister. Though we can trace no record of his opinion, that he retained the copy after reading it is telling.

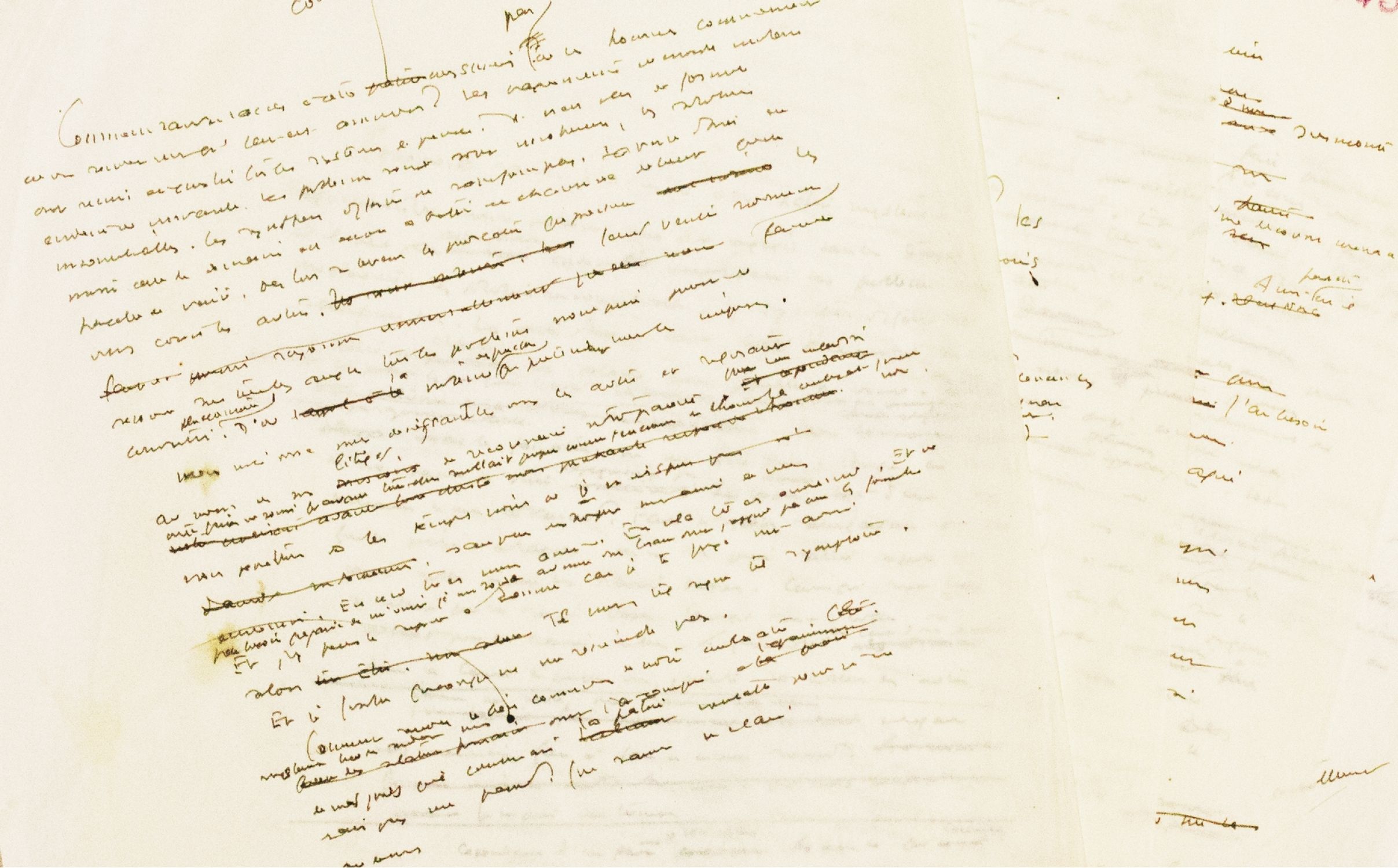

Among the more moving items at the Fair this year is this unpublished, working alternative manuscript material from Lettre à un otage by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry (New York, 1942; $10,000; Le Feu Follet, Paris). Lettre a un otage began as a preface to a novel by Saint-Exupéry’s dear friend, Leon Werth, to whom he had dedicated Le Petit Prince. These pages include previously unknown and heavily revised versions of text, including this variation: “The fracturing of the modern world draws us into a dark time where there are no longer any obvious or universal formulas. The problems are incoherent, the solutions irreconcilable. The different conciliations do not satisfy. Yesterday’s truth is dead. Today’s is yet to be created and each one holds only a portion of the truth . . .” Then, Saint-Exupéry effected a delay in the novel’s publication, instead bringing out his essay on its own. In these pages we learn why: He feared Nazi retaliation against Werth, then living in Occupied France. This is the last work published before Saint-Exupéry’s disappearance.

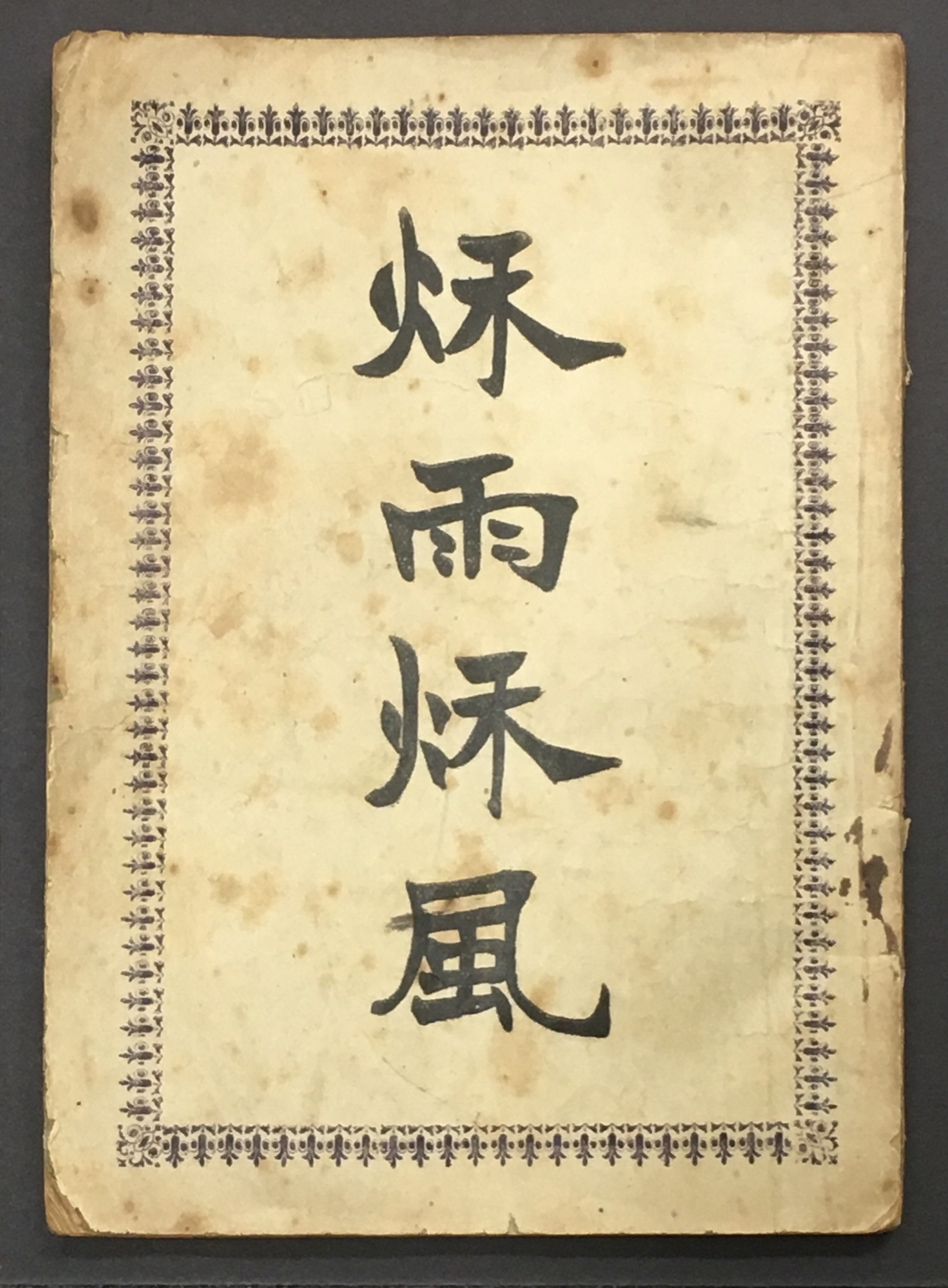

This memorial pamphlet for executed Chinese feminist revolutionary Qiu Jin was cheaply published in Shanghai and discreetly circulated in 1907 after her execution. This one bears a 1922 “paid” stamp of a San Francisco Chinese grocer, testifying to its global reach. ($20,000, Honey & Wax Booksellers). It’s one of only two documented copies—the other is in China.

An advocate of female education and women’s rights, a writer, publisher and orator, Qiu Jin (1875-1907) was ultimately captured for her work with an underground organization, tortured, and beheaded. Heather O’Donnell of Honey & Wax Booksellers notes, “This 1907 pamphlet is one of the earliest examples of an attempt to shape her legacy, including excerpts from her writings and tributes by others; the printer ran an exceptional risk in producing this memorial before the revolution.” Providing a bit of context, “Sun Yat-Sen’s revolutionary party, of which Qiu Jin was the first female member, would finally overthrow the Qing Dynasty in 1911: Sun Yat-Sen’s wife described Qiu Jin as ‘one of the noblest martyrs of the revolution.’ Today, she remains a national hero, central to modern China’s vision of itself.” She died at the age of 32.

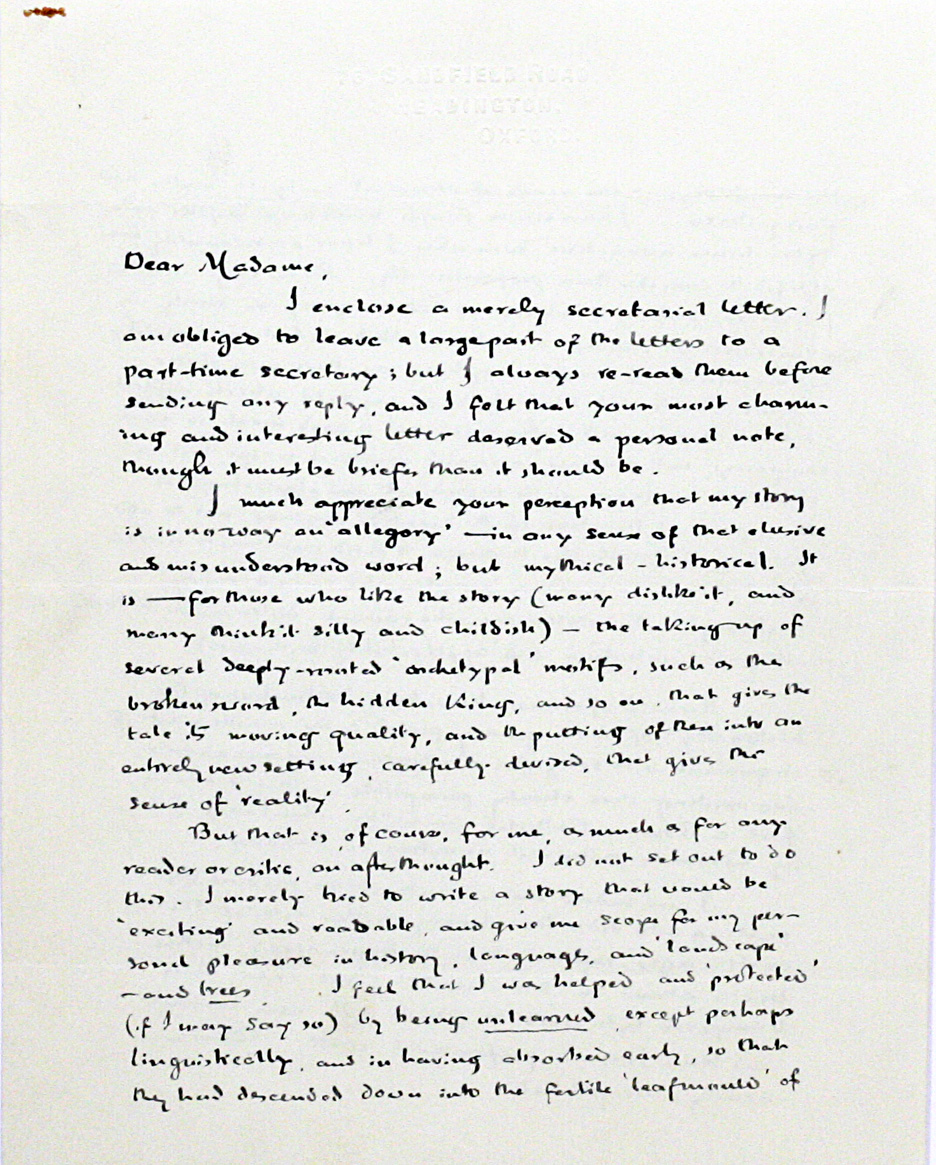

In two 1963 letters by JRR Tolkien ($48,000, Manhattan Rare Books, NYC), the man who authored several full languages for use in his fiction discusses the need, in some cases, to take language at face value.

There is no shortage of Tolkien at the Fair this year. These two 1963 letters are especially fascinating for their insight into Tolkien’s thoughts on The Lord of the Rings. In the first (brief, typed) letter, Tolkien rejects allegorical interpretations of The Lord of the Rings and admits feeling sympathy for Gollum. In the second, for some reasons inspired to revisit the subject, Tolkien writes four longhand pages in which he again addresses the ideas of allegory and symbolism; explains the poetry, the religious strains, Gollum’s repentance, and the origin of other characters; suggests a sequel; and discusses his motivation for writing the book to begin with. “I merely tried to write a story that would be ‘exciting’ and readable, and give me a scope for my personal pleasure in history, languages, and ‘landscape,’” he wrote.

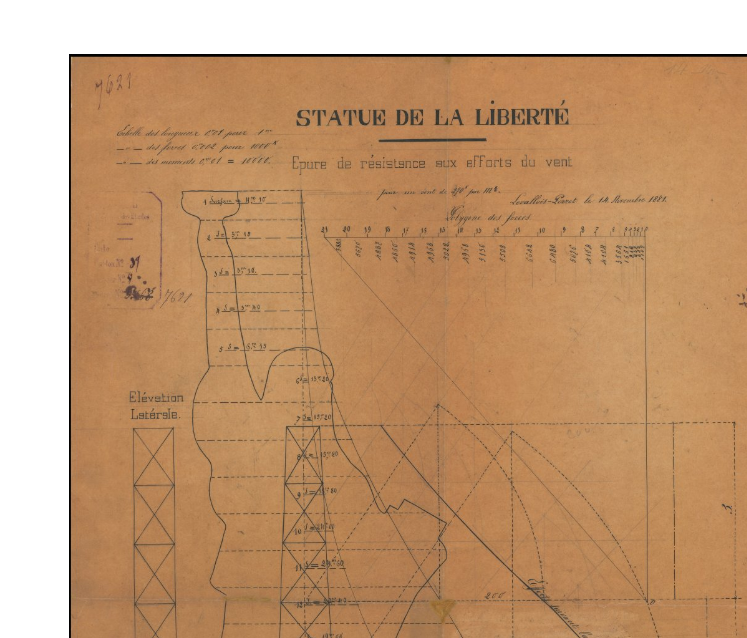

In Gustave Eiffel’s Original Drawings for the Statue of Liberty (1880 to 1883), you can see what’s behind the creation of one of the greatest symbols in modern history ($1.5MM, Barry Lawrence Ruderman).

These are all the extant original drawings, notes, and blueprints for the Statue of Liberty, directly from the archive of the Établissements Eiffel in Paris. Both the statue’s base designer Richard Morris Hunt’s set of 11 blueprints, now at the Library of Congress, and the artist Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi’s set of 10 blueprints, derived from this collection of original material (all except one image). From actual nuts and bolts, to calculations of wind resistance, to broader design issues, we see the mind, math, and pen at work behind Lady Liberty.

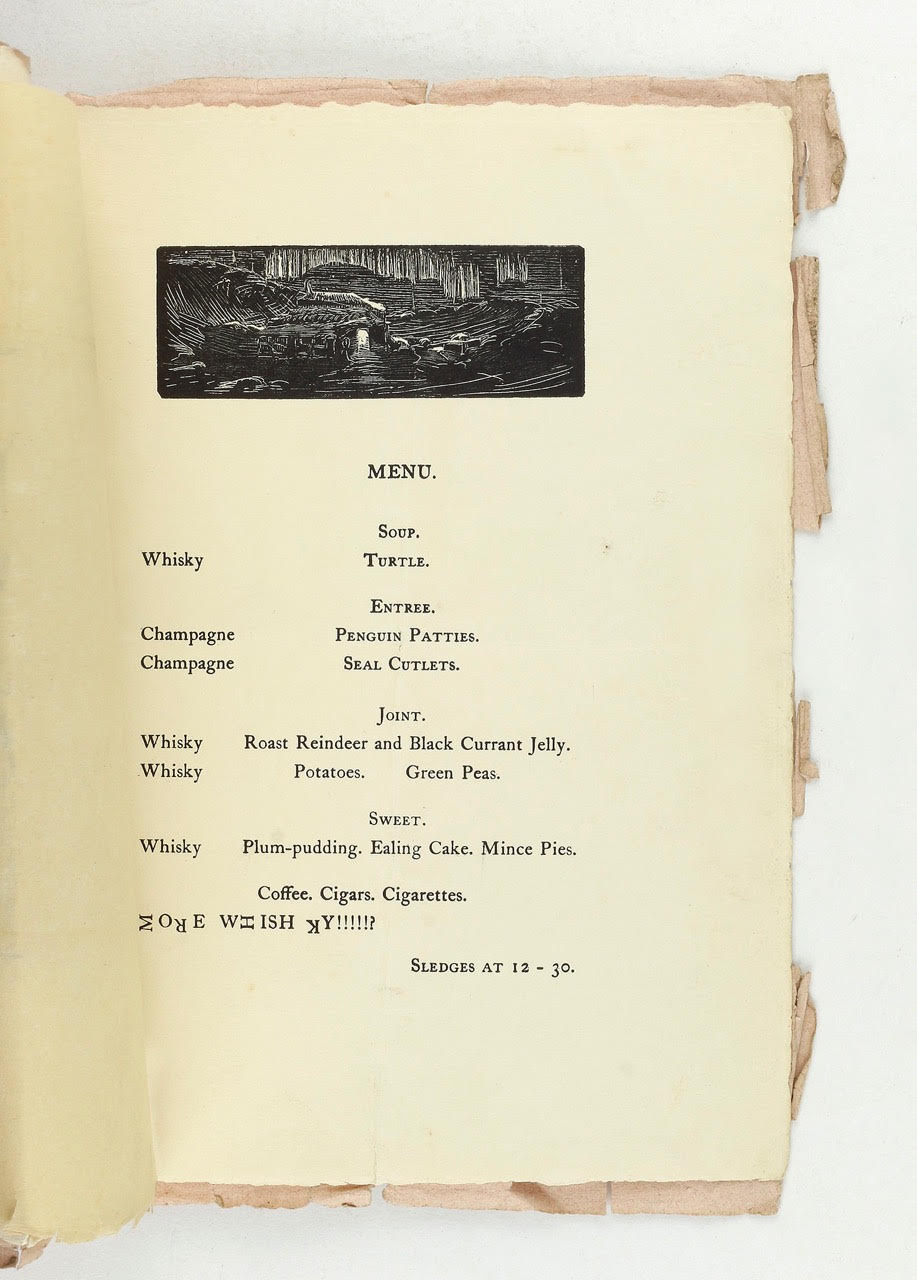

This charming menu from the Midwinter (1908) Feast of Ernest Shackleton’s Antarctic Expedition crew at their Winter Quarters, Cape Royds (1909; $20,000, Jonkers Rare Books, Oxfordshire, England) was printed and bound by members of the crew.

The printing equipment and training was provided to Shackleton’s explorer-zoologist crew by a London printer. Shackleton noted in The Heart of the Antarctic: “Joyce and Wild had been given instruction in the art of type-setting and printing, Marston being taught in etching and lithography”. After honing their skills on this menu project, they moved on to the 120-page Aurora Australis, considered “the primary incunabulum of the Antarctic” (Books On Ice), between April and July 1908. These were the only two printed works prepared at the press at Cape Royds during the Nimrod expedition.

This copy belonged to William Charles Roberts, who was both cook and assistant zoologist, leaving him well-positioned to devise such treats as turtle soup, penguin patties, seal cutlets and roast reindeer. Food-historian Micki Myers comments, “They didn’t mess about. Note the not accidental or frivolous addition of black currant jelly with the roast reindeer: apart from a berry jelly being a traditional accompaniment to venison (pairing the meat with what that meat used to eat when alive, as per tradition) it provides an essential whallop of vitamin C. Lingonberry or redcurrant would have been more apt for reindeer—but blackcurrant contains more vitamin C. And this before vitamin C had been discovered.”

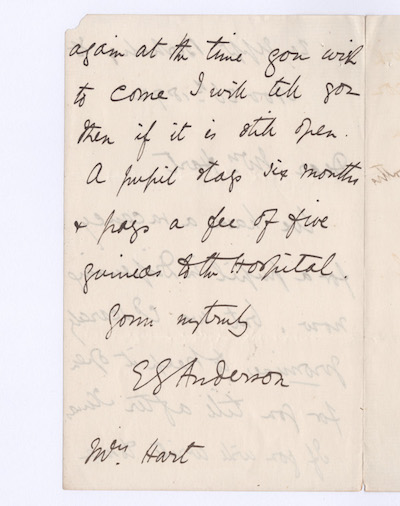

Philanthropist and social reformer Alice Rowland Hart was a force for change in a number of arenas – medicine, education, women’s rights, labor, crafts, immigration, philanthropy, the Donegal Industrial Fund, the Donegal Famine Fund, the Celtic Revival and more.

This trove of over 200 letters between 1872 and 1923 testifies to the range and efficacy of her work, coming as they do from women and men who were leaders in their fields – Octavia Hill (co-founder of the National Trust), Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, Sophie Willock Bryant and Louise Whitfield Carnegie, to name a handful. In the letters from Sophia Jex-Blake, the first female doctor in Scotland and one of the ‘Edinburgh Seven’ campaigning for women’s access to university education encourages Hart to let go of her plan to work as a nurse and instead to undergo proper medical training. Letters come too from businessmen, architects, politicians, merchants, artists, Irish campaigners, and more. (Deborah Coltham Rare Books and Alembic Rare Books, 3800 pounds)

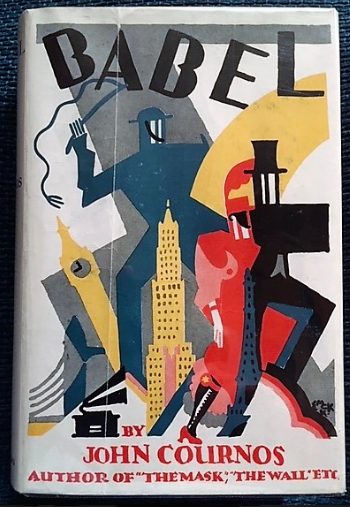

To end on, without judging a book by its cover, let’s at least appreciate some covers, in this painstakingly assembled collection of 1928-1932 dust-jackets by “The Picasso of Posters,” E. McKnight Kauffer ($20,000, Bas Books, London).

Montana-born Kauffer studied in Paris and settled in London in 1914 until the outbreak of World War II. These jackets date to the early peak of his career, when he was known in England as “The Poster King” and the mastermind behind the iconic work commissioned for the London Underground. When British publisher Victor Gollancz opened his firm he commissioned eighteen such covers from Kauffer, before turning to his uniform signature plain yellow jackets. In this collection are eight created for Gollancz, and four for the Doubleday Crime Club. Kauffer and his wife returned to the United States in 1940, and despite a one-man show at the Museum of Modern Art in 1937, and jacket-design work for Random House and others, as well as posters for American Airlines, he wrestled, finding neither artistic freedom nor commercial success. You are unlikely to come across so many striking examples of these innovative covers all in one place anywhere else.

Sarah Funke Butler

Sarah Funke Butler is a literary agent with a specialty in literary archives, and a private curator for rare book collections. She spent more than twenty years working with remarkable manuscripts, rare books and archival treasures at Glenn Horowitz Bookseller, and is Collection Manager of the Dobkin Family Collection of Feminism. @funkelit