From Ovid to Hawthorne, on the Power and Possibility of Retelling Classic Stories

“Voices we have not heard take the lead.”

As a child, I played a recording of the 1961 musical film West Side Story over and over on my parents’ phonograph, barely realizing that I was learning empathy for a group of immigrants folded inside an update on Romeo and Juliet—yet I was learning it, nevertheless.

Updates, prequels, and inspired-by works are everywhere today—in bookstores, on Broadway, and in film. Wicked or Hadestown, anyone? How about The Six, or & Juliet, opening this month at the Stephen Sondheim Theatre? Maggie O’Farrell’s Hamnet shows us William Shakespeare’s wife in her deepest humanity; Rachel Hawkins’ The Wife Upstairs is an update on Jane Eyre-turned thriller, and her latest, The Villa, is inspired by Percy and Mary Shelley and their summer of Frankenstein.

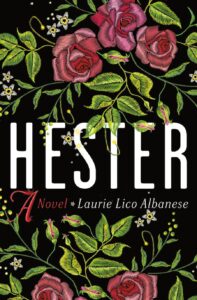

Writing my new novel, Hester, I became deeply aware of the author’s questions, concerns, intentions, and responsibility when creating fiction inspired by a canonical work—in my case, The Scarlet Letter

These retellings are often a chance for us to consider what a classic tale might look like if it were told by or about someone other than a member of the dominant power system. They offer us the opportunity to consider how archetypal challenges, struggles, and life or death questions reverberate today through other class, gender, or nationality distinctions.

Writing something inspired by a classic invites both the author and the reader to expand our vision of the original story.

Natalie Haynes’ powerful retelling of the Greek and Trojan wars in A Thousand Ships reveals the wonder of a canonical story reworked to forefront female voices. In this fresh retelling, Haynes helps us re-think Queen Clytemnestra’s murders of Agamemnon and Cassandra, not as the actions of a jealous wife killing her husband and his mistress, but as a heart-broken and raging mother avenging her daughter Iphigenia’s murder.

Likewise, when Jean Rhys wrote Wide Sargasso Sea in response to Jane Eyre, it was as if a hurricane had ripped off the shutters on a house in Jamaica and revealed the true story of Berthe Antoinette, the wife locked away in Mr. Rochester’s attic. Bronte’s novel allows us to see the woman in the attic only through the eyes of others. But why is she in the attic? What happened to her before she was put there? Was she insane, or was she imprisoned and driven to madness? Rhys’ parallel retelling of Jane Eyre turns the lens away from Mr. Rochester, our white proto-colonialist, and shows us the effects of that male colonial privilege on a vulnerable young woman.

“Reader, I married him,” is much less a victory when we know why the first wife is burning the place to the ground.

Madeline Miller’s transcendent novel, Circe, turns a minor character from The Odyssey into the enchanting heroine of her own epic, and Miller’s first novel, The Song of Achilles, foregrounds the famous Greek warrior’s love affair with his friend Patroclus. Miller is not the first to revisit the story of Achilles and his lover: while researching classic retellings, I discovered that Shakespeare (a master re-teller himself) also wrote about Achilles and Patroclus in a minor play, Troilus and Cressida. The story of two great male warriors in love with one another challenges binary perceptions of gender and sexuality, and has reached a new generation of young people hungry for such stories, thanks in large part to the popularity of Miller’s novels.

Writing something inspired by a classic invites both the author and the reader to expand our vision of the original story—to turn the prism of what is already on the page and expose a new dimension to a familiar narrative, a new framework or point of view.

Perhaps the enslaved person will tell the story instead of the enslaver. The woman instead of the man. The conquered instead of the conqueror. And we will see everything—including the history of power, ownership, voice, and dominance—anew.

I am eager for what I will learn and see anew through fresh eyes.

It sometimes seems as if a character arrives from nowhere, with a lantern, on a ship in the night, emerging from a dark forest or a long hallway. Characters can step from myth, from song, from sculpture, from history, and from literature. Do they emerge formed? Do they form themselves? These questions might be asked about our children and ourselves as easily as they are asked about our fictional characters, for these are as much questions about the self and the formation of the self—the invention of the self—as they are about the creation and use of characters in fiction.

Inspiration, not imitation is how I approached Hester, in which Nathaniel Hawthorne himself is a character, living in 1829 Salem. In Hawthorne’s classic, Hester Prynne’s thoughts and actions are filtered through the male narrator and the male gaze. She does not tell her story, so much as act in one that is dominated by men. My Hester gives a voice to the woman who wore the scarlet A as a badge of honor and not as a badge of shame. It puts the narrative in Hester Prynne’s hands.

There are surely more retellings on the way—Anne Burt’s forthcoming novel The Dig revisits Sophocles’ Antigone set in modern-day Minnesota with Sarajevan refugees—and I am eager for what I will learn and see anew through fresh eyes.

In revisiting and retelling the classics, the old is made new again. Voices we have not heard—voices smothered, locked away in an attic, or overshadowed by tales of male conquest—take the lead and tell the tale in an entirely new way that enriches us once more.

__________________________________

Hester by Laurie Lico Albanese is available via St. Martin’s Press.

Laurie Lico Albanese

Laurie Lico Albanese has published fiction, poetry, journalism, travel writing, creative nonfiction, and memoir. Her books include Stolen Beauty, Blue Suburbia: Almost a Memoir, Lynelle by the Sea, and The Miracles of Prato, co-written with art historian Laura Morowitz. Laurie is married to a publishing executive and is the mother of two children.