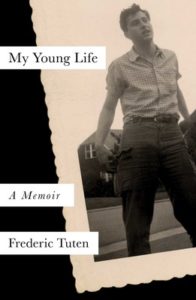

Frederic Tuten: On My Youthful Dreams of the Parisian Writer's Life

From the Bronx to Book Row and Back Again

Manhattan and the Bronx, circa 1946

When I was ten my grandmother and I went to the city—that’s what we called Manhattan—to pick up a cake from De Robertis Pasticceria, between Tenth and Eleventh on First Avenue. My mother had ordered the cake for my aunt Sadie’s birthday. There were many Italian pastry shops on Arthur Avenue, a swift 20-minute bus ride from where we lived, but none, in my family’s judgment, was as good as DeRobertis, where they would stop for baba au rhum or a cannoli when they lived on East Twelfth.

We got off at Union Square, as usual, but instead of walking across Fourteenth Street as always, we took a turn and found ourselves on Fourth Avenue, where we had never been. It took us along Book Row, the area between Eighth and Fourteenth Streets, packed with used-book stores with their outdoor stalls. I knew right away that I would go back when I was old enough to travel alone.

I seldom left my neighborhood or traveled to Manhattan, but after I turned thirteen I started taking the subway down to Book Row. The ride from Pelham Parkway to Union Square Fourteenth Street was direct, no changes or transfers, so I was not too afraid of getting lost. On early Saturday afternoons it was easy to find an empty seat and be left quietly to read a book during the hour-long ride. The subway cost a dime each way, and for another dollar or even less I could find wonderful books to haul back to the Bronx. My mother complained, “Where are we going to keep all these books?” My one bookcase made of boards held up on bricks was already overpacked and verging on collapse.

“Under my cot, Mom.” Where I had stashed the books my shelves could not hold.

One afternoon, drawn by the title, I bought George Moore’s Confessions of a Young Man from a bookstall for a dime. It had a worn, leathery green cover and distinguished gold title impressed on the spine. I read the opening pages out there in the street, and in moments I knew the book was addressed to me. It was about a young man (like me) who wanted to be an artist (like me) and yearned (like me) to find his way to become one.

I promised myself that one day I would follow him to Paris, where art and beauty counted for everything.

On the subway back to the Bronx, I continued reading, and as we ascended from the underground to the elevated tracks after 149th Street, passing the littered streets below and the brown rows of sullen apartment buildings, I felt I had met myself in a past life. Not only because young Moore had wanted to be an artist, but because he wanted to live the life of one. His Confessions teemed with names of famous Impressionist painters, of mysterious narrow streets and smoke-filled cafés, under a Paris sky thick with artistic aspiration.

I promised myself that one day I would follow him to Paris, where art and beauty counted for everything, and where extraordinary women—as I found in a book of artists photographed in their studios and on their picnics and in sexy cafés—also came with the freedom of bohemian life.

My friend Arthur, the expert who had explained to me the mysteries of sex, came over to me in the school cafeteria and said, “This is the book for you.” Arthur was the one who had passed around his copy of Mickey Spillane’s I, the Jury, dog-eared to the famous scene of a woman walking into the hero’s room and slowly unbuttoning her blouse—the scene that had inflamed a generation of Bronx youth. Arthur’s parents drove around in a Cadillac and parked it in a garage at night and they never seemed to have to go to work. They had recently returned from Paris and had sneaked through customs Henry Miller’s banned book Tropic of Cancer. Arthur filched it from their bedroom bureau and turned it over to me. “This will make you cream all night,” he said. “But you got to give it back before they find it missing.” I was thrilled to have this mysterious, forbidden book.

The edges of the pages were folded at the supposedly hot passages. The rest of the book seemed untouched. I read the whole book from first sentence to last, and a day after I finished I started over again. It was a key to the cell I lived in and offered a view of the exciting world outside the prison of ordinary life. The book sang the joy of living unshackled by social norms, conventions, the everyday lies; it was a manifesto for my liberty. Nowhere did I find the supposed sexy filth for which it was banned. There was plenty of sex, but none of it pornographic, and even if it had been, so what? What was all the fuss about? Wasn’t sex the stuff of life we lived in and lived for?

I thought it was wonderful to be spiritually lost, especially in Bowles’s world, so far away.

Tropic of Cancer tells the story of Henry, the author himself, who, at 35 and with just a few dollars to his name, sailed from New York to Paris, knowing no one there, speaking not a phrase of French. In Paris he scrounged money from fellow Americans, went hungry, and yet none of that mattered, because he walked the city like a man crazy in love. A single day wandering in Paris was a day richer, deeper, than his whole previous life in New York working at shitty jobs and starved for a woman’s caress that did not require a marriage license. Could I not one day soon do the same as Henry—and young George Moore—and live in Paris a free man?

But first I had to escape from prison. I was bored with my high school classes, with the well-meaning teachers, the students with passion for nothing—except for sex, the only passion we shared. There was nothing in school that opened me to greater poetry or fiction than I had already been reading. I was then in the world of Paul Bowles’s The Sheltering Sky, with its spiritually lost expatriates wandering through Morocco and its desert outposts.

I thought it was wonderful to be spiritually lost, especially in Bowles’s world, so far away from school, from the butcher shop and even Louie’s Luncheonette, from my crumbling apartment and my sad mother. But better than Bowles’s soulless desert was the glamorous writer’s life in Paris that I had discovered in Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises. Like its protagonist, Jake Barnes, I, too, would sit with other artists and writer friends—and worldly women—in a café where I could linger for hours drawing and reading at a table sur la terrasse, which sounded more heroic than just a table on the sidewalk.

I reread Moore’s Confessions, searching this time for practical information on how young George was able to pay his way to the city of art and light. I soon discovered the answer. He wrote: “Then my father died, and I suddenly found myself heir to considerable property . . . I was free to enjoy life as I pleased. Eighteen, with life and France before me.”

Expecting no estates to be left to me, I was bitter at my bad luck and chastised myself for being such a dreamy fool. I would have to discover my own way to Paris.

__________________________________

From My Young Life. Used with permission of Simon & Schuster. Copyright © 2019 by Frederic Tuten.

Frederic Tuten

Frederic Tuten is an American novelist and short story writer who has published five novels—including Tintin in the New York and The Adventures of Mao on the Long March. and a story collection, Self Portraits: Fictions.