A raindrop appeared in Bern’s right eye the night before his trip. A mote, a foreign object? He felt nothing, but like spatter at the edge of a thunderstorm thumping a windshield, an amoeba-shaped spot attached to his vision, fore or aft of his sight, it wasn’t clear. It swam as his eye swam, foreground to background, curvature to flatness, watery against the dark, dusky when held to a light.

He stood at the bathroom mirror in the apartment he’d been forced to abandon (he’d move into his cheaper retirement flat upon his return). He saw nothing on or in his eye, directly, though the spot continued to dart in front of him, just beyond his ability to focus on it. Momentarily, he was distracted in the mirror by his paunch, new, these last few months; since his less frenetic schedule kicked in, he’d filled the time each day after lunch by snacking on barbecue potato chips, a childhood vice restored. (Sorry, Mom.) And his mustache, also new, startled him, an unruly brown-gray thatch above his lips. He’d begun to grow it when it became clear to him that his days at the architectural firm were numbered, no longer caring, precisely, to keep up professional appearances.

He moved the mirror—glued to the door of a medicine cabinet above the bathroom sink—backward and forward, studying his eye from various angles, none of which revealed anything. A pair of bobby pins, dislodged by the fanning door, spilled from a glass shelf into the rust-stained sink. The pins had belonged to his mother. He’d kept them after she’d died. He remembered the young RNs in the nursing home in Houston—a pair of chubby Hispanic women—wondering about them during his mother’s last days, as her emphysema worsened. They’d never used such gizmos. Annie scraped up just enough strength to demonstrate for the fascinated nurses how she fixed her hair each night with the pins, lifting her arms and fastening her curls: Bern’s final memory of her animated, fully awake.

His eyesight bothered him the rest of the evening as he finished packing and watched a DVD, ordered from Netflix, on his tiny TV: a British comedy from the 1940s, I Know Where I’m Going, set in the Hebrides. His mother had always said it was one of her favorites. Bern had never seen it. Key scenes had been filmed in the Western Isles Hotel, in Tobermory, on the island of Mull. The hotel still existed, and Bern had booked a night in it. Now, as he watched the movie, he was stunned to see how much his mother had modeled her appearance on the lead actress—a short bob of hair (shaped, each night, by a phalanx of pins), stiff-shouldered blouses, and casual suit coats. The plot was a silly romance, made bearable by remarkable black-and-white panoramas of rocky coastlines and castles. He feared, if his mother had based her foundational views of Scotland on this film, which she’d first seen as a girl, her head had been padded with fluff about the country, and his own visit, in honor of her memory, might turn out to be a folly, as well. Travel was hard enough without harboring unrealizable expectations.

As the movie played, he kept rubbing his eye. He had no idea what was wrong with it (a burst blood vessel? a tear in the retina?). All he knew was that, at the beginning of a new phase in his life, he had arranged a sightseeing trip to his mother’s ancestral lands, and now he wasn’t seeing properly.

*

He took his raindrop to Scotland. On the plane from Newark to Glasgow, the woman seated next to him, a former medical technician from Queens, assured him his eye was probably nothing to worry about. ‘‘Sounds like a floater,’’ she said. ‘‘They’re pretty common as we age—how old are you?’’

‘‘Fifty-eight.’’

‘‘Well, there you go then. The back of the eye is made of this gel-like stuff, the vitreous, which shrinks as we get older and gets a little shreddy,’’ she explained, uncapping a mini-bottle of chardonnay she had purchased from the flight attendant. ‘‘Bits of protein called collagen, they break off and cause what I’m guessing you’re seeing—sort of a shadow on the retina. Annoying, but harmless. It might or might not fade with time. My advice? Make friends with it. Give it a name. You may just have to live with it.’’

“All he knew was that, at the beginning of a new phase in his life, he had arranged a sightseeing trip to his mother’s ancestral lands, and now he wasn’t seeing properly.”

She sounded knowledgeable and reasonable, but when she passed up, on the in-flight entertainment system, an array of classic movies—Casablanca, Children of Paradise, The Spirit of the Beehive—and settled instead on Robocop, Bern began to doubt her judgment. He had brought to read a very fine old Dorothy Sayers mystery, Gaudy Night, but found he couldn’t concentrate on it in the general discomfort of the cramped quarters and his surprising—new, for him—fear of flying.

Well. Hard not to fret after airport security; after that passenger jet shattered this summer by a ground-to-air missile over eastern Ukraine . . . teddy bears, toothpaste, and children’s mismatched socks moldering in muddy fields trampled by drunken teenaged renegades waving Kalashnikovs; other drunken teens marching in the streets of Paris, Bonn, and London, shouting, ‘‘Death to the Jews!’’ after Israel’s latest invasion of Gaza; Westerners beheaded by hooded thugs declaring allegiance to Allah: everywhere, it seemed, a return to balls-out tribalism, in Catalonia, Egypt, even Scotland—Bern was traveling just ahead of a national referendum to determine whether Scotland would declare its independence from England.

Bless my sweet bastard blood, he thought, and the globe’s break-back morphology. What we need is more continental drift to put an end to all this nonsense.

He tried to relax. Five more hours in the black, bumpy air. ‘‘Finn McCool,’’ he read distractedly in an airline magazine plucked from the seat pocket (‘‘Fifteen Fun Facts for the Overseas Traveler’’). ‘‘A legendary figure in Ireland and Scotland, a warrior-hero said to be immortal and capable of assuming the dimensions of a giant.’’ Then the story disappeared into a series of Duty Free ads.

Still fidgety (surely, somewhere over the planet, these pilots could find smoother air), Bern plugged headphones into his seat arm and sampled the music on offer. The rock was too raucous, timed, it seemed, to the plane’s turbulence; the classical too bland. Finally, he chose an anthology of sitar tunes. The drones lulled him into a meditative state—an elegiac mood of reassessing recent changes. The songs’ repeated phrases reminded him of a concert he’d attended not long ago on the Lower East Side, another day he’d needed calming, when the idea of flying to Scotland first took root. It was during his first official week as a retiree; he wasn’t quite sure how to spend his afternoons.

Originally, the concert had not been on his agenda. Instead, just after lunch that day (split pea soup, he recorded obsessively in a notebook—what else was he going to do but log his days now as though tracking a construction project?), he’d braved tourist swarms to see what progress the city had made in reclaiming the World Trade Center acreage. For over a decade now, this had been the city’s main architectural challenge, and he’d kept regular tabs on it. What would he feel there now, he wondered, no longer a professional, just an ordinary citizen swerving by? The neighborhood—no surprise—was still a sprawling construction zone: steel beams, cranes, dust in the air, collapsible scaffolding, concrete barriers lining alleys, deflecting foot traffic. The long-awaited memorial, now open to the public, consisted of two pools, north and south, set in the original footprints of the Twin Towers. Thirty-foot waterfalls plunged into the pools and then into deeper voids in the centers of the squares: from the viewers’ vantage points, these voids appeared to be bottomless. Around the watery graves, the names of the 9/11 victims had been inscribed in bronze parapets, showing signs of wear, already, from all the touching.

‘‘This is sacred ground. Please be quiet and respectful,’’ read large signs on chain-link fences. Yet with all the building noise, nearby restaurants, billboards advertising new retail space, and the gauntlet of security each visitor had to pass in order to enter the courtyard—belts off, shoes off, empty your pockets—it felt more like a theme park run by the TSA.

The overwhelming sensation invoked by the pools was one of falling, Bern thought: buildings falling, people falling from buildings—the indelible images of that terrible day, captured by, and repeated over and over on, television. Gray foam pitching into steep, square declivities. The place memorialized the event, not the people who died here, Bern decided—not the way I’d have designed it. But then I’m no longer a working planner. I’m an old and useless man. He looked around. He was a good twenty or even thirty years older than everyone else on the street. Block after block, kids must be packed seven or eight to a room each night, sleeping on floors or fold-out couches, he thought. How many of them even remember 9/11? They worked as waiters or baristas while planning ambitious futures. He was astonished to realize he no longer saw himself as a man with a future—not in the way these youngsters thought of time and chance and opportunity. It wasn’t possible that most of them earned enough money to make it on their own. They must be supported by their mothers and fathers. Doddering folks in Iowa, Nebraska, and North Carolina, surrounded by brittle cornstalks, are subsidizing this poor, wounded city, Bern figured, sending monthly checks to their hopeful chicks.

The island ran on coffee and hormones, sugar and salt and alcohol.

‘‘Excuse me, sir. Anything to drink?’’ He ordered a pinot noir from the flight attendant, closed his eyes, and returned to New York—ever more distant to him now, since his retirement. Without city projects to work on, he didn’t know how to engage with the place. Was this why he’d needed a break from it? Why he’d really bought a ticket to Scotland? Acknowledge the estrangement. He understood that, by indulging his thoughts this way, he was conducting an exercise in grief, similar to what he’d felt when his mother passed.

“He was astonished to realize he no longer saw himself as a man with a future—not in the way these youngsters thought of time and chance and opportunity.”

When he’d left the Trade Center site that day, he’d strolled past city hall, up through Chinatown. The few middle-aged men he saw looked exhausted and wan. Or was he projecting? On Chambers Street, he passed a fellow wearing a fedora and a cotton suit, clutching a single wilted lily. He might have just stepped off an Old World boat, headed for a funeral.

On Avenue B, where the ground had once been a salt marsh, a coastal wetland housing seabirds and other waterfowl (Bern knew this from the area’s history of building-code restrictions), tiny flashings caught his eye. Fireflies! He hadn’t seen fireflies since the day he’d let his mother go.

The bugs also circled the flowers and bushes, herbs and vegetables in the Sixth Street & Avenue B Community Garden. On the garden’s music stage, a concert was beginning—evening ragas performed on flute and tabla, behind a pre-recorded drone. Bern took a seat on the remnant of a willow tree that, someone told him, had toppled during Hurricane Sandy. About sixteen people gathered near the stage—surrounded by hostas and hellebores, cyclamen and kale—to hear the soothing music. It was not the type of disciplined performance his mother would have appreciated, but he thought of her again because of the lightning bugs, and the sounds seemed sacred to him, sinuous and soft. Ceremonial. Unlike her funeral, which had been ruined for him by a clumsy and indifferent Methodist minister.

Here was the thing about his mother: when she knew her time was short, she demanded a Christian service. No Kaddish. No sitting shiva. No rush to interment. The family’s Judaism had always been a loose-fitting garment, and the Scot in her fully emerged, as it often did year after year. ‘‘I want a priest,’’ she said. In her dwindling days, curled in her bed in the physical rehabilitation facility like a wadded-up old sheet (did the nurses never wash her?), she asked to see picture books from her shelves at home featuring photographs of the abbey on Iona. ‘‘If I could only be buried there,’’ she said. ‘‘It’s consecrated ground, you know.’’

In the family’s haste, confusion, and grief after her death, they found a minister instead of a priest, a man who’d never known her and had nothing worthwhile to say about anything, including the Jesus he claimed so passionately to adore. The fireflies circling the cemetery in the yellowing dusk were the day’s only memorable touch.

Occasionally, during the garden concert, an ambulance hee-haw interrupted the ragas—the flute would linger on a high note, waiting for the noise to subside. Bern shut his eyes. As he swayed to the drone, recalling his mother’s deathbed references to Iona, he remembered his long-ago promise to her. In addition to his pension, he’d been given a one-time payout for taking early retirement. He could use that money to finance a trip overseas. Why not? he thought. What good was he doing anyone here? A solitary man. A man with no work.

On the plane, now, he glanced at the screen on the seat back in front of the woman beside him. Robocop’s credits rolled across it. Three more hours. He rubbed his face. Finn, he thought, watching his raindrop drift around the aircraft’s cabin. I’ll call you Finn McCool, and pray you don’t become a giant in my eye. How do you do?

__________________________________

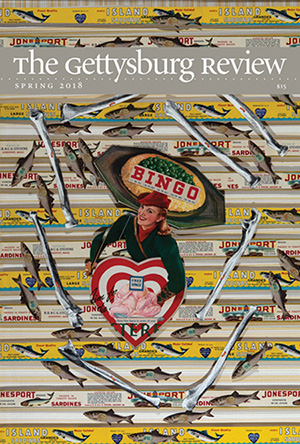

From “Frank at the End of the World” in the latest issue of The Gettysburg Review. Used with permission of The Gettysburg Review. Copyright © 2018 by Tracy Daugherty.