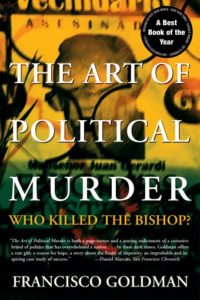

Francisco Goldman on Guatemalan Justice, Identity, and The Art of Political Murder

In Conversation with Idra Novey About the New HBO Adaptation of Goldman's Classic Work of Reportage

Many years ago, the writer Rivka Galchen loaned me Francisco Goldman’s first novel, The Long Night of White Chickens. The musicality and irreverence of the title was equally manifest in the verve of the writing, and in the novel’s searching questions about a life lived in both English and Spanish at once. I kept returning to White Chickens while working on my own first novel and have been an eager reader of Goldman’s books ever since. His groundbreaking work of nonfiction, The Art of Political Murder, was adapted into a superb documentary released this month with HBO and I had the honor to ask him, over email from his home in Mexico City, some questions about the interstices between this adaptation for HBO, our present moment, and the challenges of writing about violence in his forthcoming novel Monkey Boy, out next year.

*

Idra Novey: The Art of Political Murder centers on the murder of a Guatemalan bishop in 1998 who’d just delivered a public statement about military crimes during the civil war that ended two years before, in 1996. In the documentary, you describe how the trial became a test of the Guatemalan justice system. Could you talk about any parallels you see in how the justice system has been tested in the United States under the Trump administration?

Francisco Goldman: That 1998 Catholic Church report on the atrocities of Guatemala’s long civil war, directed by Bishop Gerardi, shattered the long silence imposed by terror in Guatemala, and declared the Army responsible for 90% of the war’s tens of thousands of civilian killings. Nothing threatened the Army’s hold on real power—the democratization measures of the 1996 Peace Accords would be easy to undermine or ignore—as much as the possibility of officers on trial for crimes against humanity.

Impunity provides great “artistic freedom” to state killers, the time and space to plot an incredible crime, “a work of diabolical genius,” as one of the bishop’s associates says in the book. Bishop Gerardi’s murder was meant to do more than just eliminate an enemy. It was a theatrically faked crime of passion designed to have manifold effects: to discredit the bishop and the Church; to sow macabre titillation and mass confusion; to send out warnings that would be understood by those they were intended for; et cetera. The Army, or those who planned and carried out the killing, never expected to be realistically investigated, or that they could eventually face a trial and prison. Why would they have if they really never had before? They knew who the prosecutor was going to be, and that police would never investigate. They had nothing to fear from the government.

So you can say that there really wasn’t a justice system to test.

What was being tested was the peace. This was a monumental crime that took place in peacetime. Would the country now somehow collapse back into war and military dictatorship?

But what the killers, their backers and the many actors playing supporting roles in the cover-up, in the corrupt media disinformation machine and so on, never foresaw was that a small group of young people working from inside the Church human rights group (ODHA) the bishop had founded were going to conduct their own investigation, and that it was going to be so consequential: discovering evidence, witnesses, and adroitly wielding this information. It should have been a slam-dunk case: blame it all on Father Mario and his dog, the crime of passion scenario.

So that’s the story told in the documentary, covering the first part of the book, from the murder to the 2001 trial. I was lucky to be allowed inside the ODHA, to accompany its lawyers and that team of young investigators through a lot of it. For me, the core of this story—what kept me riveted over the nine years I followed the case, until the final appeal upheld the convictions—was always the human story. Just the way a crime is a human creation—the Gerardi case has a phenomenal cast of villains—so are a criminal case and a fight for justice. First the ODHA, then the courageous prosecutor who inherited the case, the judges finally seated at trial, what they proved was that justice was possible in Guatemala. Partial justice, I should say, because the military men finally convicted were part of a much larger operation. But partial justice in a country where justice hadn’t been possible before is historic.

The Gerardi case essentially brought the Guatemalan justice system into being.

Then Trump very nearly destroyed it. Let me explain a bit. Via a process I won’t describe here, the Gerardi case led to the establishment in Guatemala of a trailblazing U.N. crime fighting commission known as CICIG, the International Commission against Corruption and Impunity in Guatemala, with international prosecutors and investigators working with Guatemalan counterparts. If throughout the Cold War, Guatemala’s all powerful Military Intelligence units had relied on the largesse of the CIA, in its aftermath they found an even more lucrative partner, organized crime, narco cartels. Guatemala became a major narcotics transshipment point. By 2006, when CICIG was established, Guatemala was becoming a failed state, its institutions captured by corruption and organized crime. CICIG was a way to fight back. The Gerardi case had shown that Guatemalans had courageous and talented prosecutors and judges willing to go all the way, but they needed international support. CICIG had unwavering bipartisan support in the U.S., which for a decade provided much of its funding. CICIG and Guatemalan justice couldn’t entirely hold off the cartels’ corrupting powers, but they had a lot of successes—in 2015, sent ex-general President Otto Pérez Molina from the presidency to prison on the same day on corruption charges (a key witness had accused Pérez Molina of a role in the Gerardi murder)—and were becoming ever more adept and stronger.

In Guatemala, for good reason, everyone is disillusioned and cynical about pretty much everything, yet in poll after poll CICIG had 70% support.

Honest prosecutors and judges preserve democratic institutions by keeping them from being captured by the criminal corrupt. You can’t have a working democracy without them.

In 2016 Guatemala elected a mini-Trump as president, Jimmy Morales, a TV comedian who performed racist skits in black face, Trump’s kind of guy, a notorious degenerate and total cretin. The Guatemalan corrupt knew it was their time. The slime called out to the slime. U.S. lobbyists, hired by corrupt Guatemalan pols, reached out to such as Senator “Little Narco” Rubio, who cut off congressional funding for CICIG, a fatal blow, which he justified with lies. Meanwhile “mini-Trump” learned he was being investigated by CICIG for corruption. There can’t be much that Trump despises more than anti-corruption prosecutors. The Trump administration silently watched as Morales expelled CICIG, fired Guatemala’s valiant Attorney General Thelma Aldana, and replaced her with a Barr-like toady. Morales nearly destroyed the Guatemalan justice system in order install a toy-town version of what Trump dreamed of establishing in the U.S. In the US, our institutions seem to have held up, but in Guatemala, not so much. It’s a good illustration of how essential a functional justice system is to a democracy. Honest prosecutors and judges preserve democratic institutions by keeping them from being captured by the criminal corrupt. You can’t have a working democracy without them. Guatemala couldn’t have withstood another four years of Trump. Biden was always a very strong supporter of CICIG, and his win has actually brought some hope to Guatemala.

Novey: What has the response been in Guatemala to the release of this documentary?

Goldman: The response has been extraordinary. (#1 trending topic in Guatemala!) Such an outpouring of emotion, recognition and even vindication for the people who participated in the case and in the film or who are depicted in it, most of whom are still working as prosecutors, investigators, judges, journalists, or who are major human rights leaders to this day. Younger people have especially been posting about how eye-opening and inspiring the doc is for them. The past months have seen big protests against corruption and the sabotaging of the justice system in Guatemala, it’s around those issues that the current battle for democracy and the future is being waged, so the timing couldn’t be better.

Author Francisco Goldman (Mathieu Bourgeois)

Author Francisco Goldman (Mathieu Bourgeois)

Novey: I know you finished a novel recently and I wondered whether you were collaborating on this adaptation of your work as an investigative journalist while crafting this new work of fiction. If so, were there any surprising ways this adaptation found its way into your thinking about the new novel?

Goldman: While Rise Films, and our director, Paul Taylor, prepared and filmed, I wasn’t doing any journalistic work. We talked about the case a lot, and I helped put them in touch with people, and flew down several times for the filming, in Guatemala and to another country for the interviews with the exiled Witness who still lives in hiding.

It does have a place in Monkey Boy, my new novel. This book is autobiographical in some ways, the narrator is named Francisco Goldberg, but as that nip-and-tucked surname also suggests, its adamantly fictional too. This is not something I’m so conscious of while actually writing, but I suppose it’s about creating distance from my own experiences even as I’m trying to find meaning through fiction, or else just trying to change them into something else, that thing you don’t know you’re looking for until you find it or it surprises you, via style, form, invention, everything else I can summon. It’s speculative too: what might my life have been like if this major tragic event hadn’t happened, or if instead something like this had. The narrator, after many years living in Mexico City, has recently returned to live in New York, for reasons related to the case of the bishop’s murder. He has a lot more going on his life, in his mind and heart than that, though. He doesn’t really have to try very hard to push the case from his mind, but it comes back, and not just in his thoughts and memories.

The novel takes place over a five day trip home to Boston, to see his mother in her nursing home, as well as two Guatemalan women who helped raise him, and also his great unrequited teenaged love. Throughout and inside this little trip, he’s in a sort of conversation with himself about his whole life, family, childhood, failed loves, his current unlikely love, his upbringing in suburban Boston and Guatemala, his years in Central America during the 1980s, and so on. This conversation is told narratively, as if he’s remembering through story, so it’s implicitly a fictional and fictionalizing voice. That five day trip home took seven years to write—seven years and thousands of discarded pages, stretches of irrational joy and satisfaction that I can’t even begin to explain even to myself. What I was looking for and what my narrator was looking for over all that time aren’t the same thing, of course. All I can really say about what the narrator is looking for is finally very simple: he wants to find his way.

Since my involvement began in 1998, that case has lived on in my life even when I’ve wished it wouldn’t, an often secret part of my life.

A lot of this is about the way his life is split, between nationalities, religions, the several ethnicities inside his one body, and a defiance of the easy categories others so like to impose. It’s also about the consequences, short and long term, of choices over a lifetime. One of those is the case of the bishop’s murder. Since my involvement began in 1998, that case has lived on in my life even when I’ve wished it wouldn’t, an often secret part of my life. It can seem to have nothing to do with my other lives: teaching creative writing and literature courses at Trinity College one semester every year; my New York City life, my Mexico City one; my life as a husband, a widower, a husband again, a man to whom fatherhood came late, and so on. Always lurking behind, or on the other side of all that, is this ongoing case in Guatemala, sometimes actively intruding, but otherwise as if breathing and lurking beneath the surface of a dark lake. By some of this I simply mean my ongoing relationship to the case, and my relationships with those involved in it, by now we really are like a tight family, many of us. The case gave me responsibilities, things to stay on top of; secrets I have a duty to keep. Also the “invisible third rail” of that close proximity to evil; that’s lessened in recent years, but used to be very present.

The Gerardi case brought the best people I’ve ever known into my life but also the very worst, and sometimes the latter would reach out and touch my life, overtly or more subtly, in horrifying or revolting ways, threats, lies, slanders, a very dark atmosphere, people you just didn’t want in your life, defamers for hire, some true human grotesques, you wouldn’t believe how low they can go, but there they were, and still are. Of course so many of the people involved in the case put up with much worse than I did. But that darkness was something I used to work to keep hidden inside, I didn’t want Aura, when we were together, to be affected by it, and likewise I am that way still, with Jovi. It lives in surreal juxtaposition to so much of the rest of my life. And in my novel I wanted to depict or examine some of the strangeness of that reality.

Some of the most important potential witnesses in the Gerardi case fled, as undocumented migrants, to the US. I was the expert witness at the asylum case for one (she won asylum.) They live here nearly anonymously, with their secrets that could be so important if you could ever bring them to trial. Now and then powerful people from Guatemala, or people connected to them, come into the U.S.—with visas, of course—to track those witnesses down and threaten them, to let them know the price they and whatever family left behind in Guatemala will pay should they cooperate with investigators. Yes, that happens, and I did want to work that into the novel.

Novey: Your glorious first novel, The Long Night of White Chickens, also has a protagonist, Roger Graetz, who is reckoning with two vastly different family histories in Guatemala and the United States. That book came out in 1992, well before the publication of The Art of Political Murder in 2007. What contrasts do you see in the psyches of Roger Graetz and in that of this new protagonist, Francisco Goldberg, in Monkey Boy, given all the ways the relationships you came to form while working on The Art of Political Murder shape the inner conflicts of Francisco Goldberg?

Goldman: Well, first of all, thank you for those nice words about that long-ago novel, and for doing this interview too! But, really, in Monkey Boy, “Francisco Goldberg’s” inner-conflicts have been much more shaped by his family history and youth, his various (failed) loves, and also his years in Guatemala and Central America in the 1980s, when he was in his twenties, than by the case of the bishop’s murder; but, yes, that case does occasionally intrude on his present circumstances, sometimes like an invisible hand coming down to move a chess piece, or to take one off the board. Those years living in Guatemala, starting in 1979 soon after college and on, through the next decade, traveling around Central American doing some freelance reporting to support myself, but mostly living in Guatemala City, eventually trying to write my novel, I consider all that my true university. Living so close to the horrific violence of those years, that era’s epic political tragedy, but also the insane surrealism and ludicrous comedy of it, the heartbreak, sordidness, beauty, love, the astounding courage and generosity I got to witness up close, and also the vileness. That did permanently mark me, as did the struggle to incorporate what I’d witnessed into my writing, a complete necessity if I was going to write at all.

How to make literary fiction that wouldn’t be overwhelmed by the violence of reality, that wouldn’t just be political protest, that same rite of passage famously undertaken by so many of the Latin American writers before me, as well as by writers of my own generation like Bolaño, Castellanos Moya, Rey Rosa (the same challenges confronted by some of the exceptional younger writers in Mexico today: Cristina Rivera Garza, Yuri Herrera, Valeria Luiselli, Fernanda Melchor, Brenda Navarro; elsewhere in Latin America too, such as Alejandro Zambra’s unique perspective on the Pinochet years in his fiction.) I was in my late twenties when I started Long Night in Guatemala City. So Roger is really almost a self-portrait of my young self, written while I was living more or less what he was living. He’s an innocent, and despite his partial Guatemalan roots, really a Massachusetts suburban kid. I haven’t reread the novel, but what I value about it is that I like to think that wartime Guatemala City is palpably alive in it, as is Roger’s experience, the shock and fear and lunacy, but also a young person’s lived, often calamitous education there. Monkey Boy is set a quarter of a century later, and looks back on some of that from a perspective certainly no longer innocent, or if some innocence remains, it’s not about the same things, more the result of adult flaws or inhibitions. “Francisco Goldberg” has lived a whole life, and what he lived through in Central America was formative, but he still, hopefully, has a lot of living ahead.

The event that most marked Francisco Goldman’s life doesn’t even occur in Francisco Goldberg’s novel, but it’s present, in a subterranean way, as it is in everything I write (and do) because the 2007 death of my wife, Aura Estrada, from injuries incurred in a swimming accident in Oaxaca, of course impacted my life in a way nothing ever had before. I think one reason Monkey Boy took so long to write was because my life was so drastically altered several times over the course of the writing, finally coming out of grief, falling in love with the Jovi, the death of my mother, the 2017 Mexico City earthquake in which we lost our home, and, especially, the birth of our daughter Azalea in 2018. All that, a series of internal quakes, must have ongoingly put a lot of cracks into my intimate voice too, demanding a series of repairs and readjustments.

Colm Toíbín, who was friends with both Aura and me, once remarked that writing The Art of Political Murder had prepared me to write Say Her Name, my novel inspired by Aura and her death and the aftermath of grief. He was so right! And not only because the narrative of Say Her Name adopts a sort of forensic frame for an investigation of literal and existential culpability. In the bishop book, I wanted to keep myself out of the narrative as much as possible, I wanted a transparent style that would allow me to stay close and shine a lucid light on what was a very complex criminal case. That voice served me well, refined further, in Say Her Name, where I wanted a transparency in the style that could bring the reader as close as possible to Aura; and bring me close too, writing not just from memory but also in imagination, in scenes from her life that I hadn’t witnessed, or when I occasionally tried to “keep her close” by imagining, making-up, playful fictional moments between us. Now, in Monkey Boy, this intimate voice came naturally to me, whenever I needed to drop down out of the narrating or introspective voice into the intimate scenes and conversations that “Goldberg” has with his mother, his former adolescent flame, and others he visits on his trip home.

Idra Novey: If Francisco Goldberg from Monkey Boy met Roger Graetz in a fictional scene, knowing what is in store for Roger in the coming years, living through the war in Guatemala City and nearly a decade after that, researching The Art of Political Murder, what insights do you think Goldberg might tell him?

Goldman: Francisco Goldberg would tell Roger to never share a conversation you’ve had with a source with another source, unless given explicit permission. Never betray a secret, or barter information. Learn how to listen, pay attention, don’t interrupt. Trust and follow your intuitions, but also make it a rule to try to double source, at least, all evidentiary information. The greatest compliment I received about that book came from Rafael Guillamón, a professional Spanish government investigator in Guatemala with the UN peacekeepers. He never talked to journalists, only to Claudia Méndez, who finally got us together, and we became friends. His own discrete but sustained, intrepid investigation into the case was so crucial to me. After the book came out he said he’d been so surprised by all that I’d managed to find out, that I’d always given him the impression that I knew little more than what he could tell me; now he assumed that I’d been that way with everyone I’d spoken to, that it was my method. It’s also important to have some trusted allies and friends who share your obsession with the case, who you can work in partnership with, for me that was Claudia, and also the ODHA lawyer Mario Domingo, I spent seemingly infinite hours talking about the case with those two especially. But Roger already knows the value of that through his friendship with Moya. Their fictional investigation into Flor’s death in Long Night prepared Francisco for the real life one into Bishop Gerardi’s murder.

Francisco would also tell Roger to be sure to have Sharon Delano as his editor. She was my editor at The New Yorker when I wrote the first article on the case, and later Morgan Entrekin hired her to edit the book. She became as obsessed with the case as I was, she’s a superb if demanding editor, and it wouldn’t have been the same book without her.

Idra Novey

Idra Novey is the author of the novel Those Who Knew, a finalist for the 2019 Clark Fiction Prize, a New York Times Editors’ Choice, and a Best Book of the Year with over a dozen media outlets, including NPR, Esquire, BBC, Kirkus Review, and O Magazine. Her first novel Ways to Disappear, received the 2017 Sami Rohr Prize, the 2016 Brooklyn Eagles Prize, and was a finalist for the L.A. Times Book Prize for First Fiction. She teaches fiction at Princeton University.