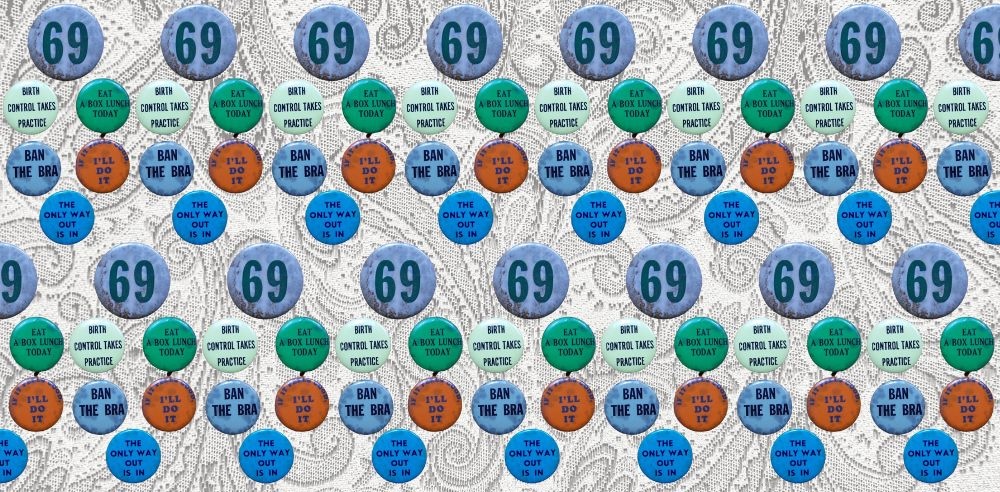

Francine Prose on the Unfinished Sexual Revolution of the 1970s

“We were not supposed to notice the gap between what we were supposed to feel and what we felt.”

In that era of so-called sexual liberation, it was illegal in Massachusetts to prescribe birth control to an unmarried woman. In college, I’d lied to get the pill. I’d made sure the doctor in Boston knew that I was a doctor’s daughter. He had family photos around his office, a wife and a son and a daughter. I hoped he would see some version of his daughter in me and at least pretend to believe that I was married. He wouldn’t want his daughter getting pregnant out of wedlock. Abortion was a serious crime, as it would be for several more years. When my best friend in high school got pregnant, she’d had to go Puerto Rico for an abortion, accompanied by her bewildered, immigrant parents.

None of us were certain about what sex meant or didn’t. Was it a recreation or a commitment? How did you keep the heart from being confused by the body? And what did any of it have to do with love, whatever that was? You slept with people you met at a dinner party, with fellow guests staying with mutual friends. A friend brought home a guy who lived in a cave and whom she’d picked up at a swap meet in Orlando.

None of us were certain about what sex meant or didn’t.

You didn’t expect sex to be more than it was. It could be transcendent. Or not. You pretended to have no expectations, even when you did. Sometimes you had sex with someone because it seemed less complicated than saying no, though you knew that the person would have been perfectly gracious if you refused. There were frequent misunderstandings. Possessiveness and jealousy were embarrassingly old-fashioned. Monogamy was slated to be smashed without anyone’s heart getting broken, so why were Janis Joplin and Joni Mitchell singing about heartbreak?

Sex was a political act, part of being free. I can’t remember ever hearing the tone I sometimes hear now when women describe their relationship to hookup culture: a mixture of sexual boasting and Puritan self loathing. We were supposed to have control over our own sexuality. No one was supposed to make us feel guilty about it. We were not supposed to notice the gap between what we were supposed to feel and what we felt. How often I’ve written supposed to in a passage about freedom.

In that window between the availability of the pill and AIDS, as long as you had birth control and STD protection—and sometimes even if you didn’t—you could have sex with people just to see what it was like. A plague of sexually transmitted crab lice spreading through a group of my friends in New York, revealing a web of secret connections.

This is not a boast about how young and hot we were. If youth was a prerequisite, hotness rarely was. It was secondary to enthusiasm, curiosity and desire. You learned that sex could be better than drugs, better than the best drug. Alternately, it could seem like a truly weird thing for people to do.

*

On the day before my wedding, my husband-to-be and I and his best friend—his best man—spent the afternoon in a Manhattan theater watching the Andy Warhol/Paul Morrissey film, Chelsea Girls. When my husband-to-be went to buy popcorn, his friend and I made out and, when he returned, his friend and I held hands in the dark. I told myself it meant nothing. We’d simply been cutting the boredom of a three-and-a-half hour black-and-white film in which nothing happens except Bridget Berlin shoots herself up, in the ass, with speed. Did my husband suspect what his friend and I had done? I never knew, but later I remembered that afternoon with guilt when I read Elizabeth Bowen’s novel, The Death of the Heart. The flash of a cigarette lighter, in a cinema, reveals that young Portia’s beloved, a hustler named Eddie, is holding hands with the woman on his other side.

I’d spent my first night in San Francisco with that same friend of my husband’s, his former best man. He had moved out West after college to work at a tech firm. After that night together, my husband’s best friend was surprised that I was leaving to go stay with my friends, Henry and Grace. I was surprised that he’d thought I’d traveled across the country to live with him. The conversation that clarified things was painfully awkward, as such conversations always were, despite how casually and glibly we had learned to talk about freedom and sex and desire, despite how we’d learned to pretend that our plans and intentions were the result of passing impulses or crossed signals.

*

On my second night in San Francisco, Henry and Grace asked me to go out and buy avocados at the 24-hour supermarket a few blocks down the hill. Everyone wanted guacamole. Everyone was high. It was midnight.

You learned that sex could be better than drugs, better than the best drug. Alternately, it could seem like a truly weird thing for people to do.

In Cala Foods, a heavenly fluorescent radiance shone down on the gorgeous California produce, the perfect artichokes, the museum-quality avocados. The only other customers were a half-dozen drag queens, in full beards, feather boas, chest hair and satin gowns. They skittered like butterflies, only louder, maximizing the drama of stuffing family-sized bags of candy corn into their shopping baskets.

I believed that they were angels sent from heaven to announce—cue the trumpets—that I had traded the darkness for the light. Whoever these marvelous creatures were, they were not like my fellow students in the Harvard English department. I felt dazzled, like Dorothy leaving black and white Kansas for a world redecorated in the rainbow pastels of a children’s breakfast cereal.

Where were the odds of finding a perfectly ripe avocado? In Cambridge zero. In San Francisco apparently one hundred. I got tortilla chips, in case Henry and Grace didn’t have any. It was just beginning to remember how it felt to be normal, not to be scared. The kid at the counter could hardly ring up my purchases, he was so enraptured by the glitter and gowns and wigs.

Back at the apartment, I learned that my fellow shoppers were celebrities: The Cockettes! A wildly original theater group, led by the inspired Hibiscus, the troup performed in the Nocturnal Dream Show at the Pagoda Palace Theater, staging their loopy, hilarious plays: Tinsel Tarts in a Hot Coma! They’d made a wonderful film, Tricia’s Wedding, about Nixon’s daughter’s White House moment of glory, a merry drag ball that descends into orgiastic violence when Eartha Kitt spikes the punch with LSD.

A random Cockettes sighting on my first night in San Francisco! Everyone agreed that it was a good sign. The guacamole was delicious, and my hosts thanked me for remembering to buy chips.

__________________________________

From 1974: A Personal History by Francine Prose. Copyright © 2024. Available from Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Francine Prose

Francine Prose is the author of twenty-two works of fiction including the highly acclaimed The Vixen; Mister Monkey; the New York Times bestseller Lovers at the Chameleon Club, Paris 1932; A Changed Man, which won the Dayton Literary Peace Prize; and Blue Angel, which was a finalist for the National Book Award. Her works of nonfiction include the highly praised Anne Frank: The Book, The Life, The Afterlife, and the New York Times bestseller Reading Like a Writer, which has become a classic. The recipient of numerous grants and honors, including a Guggenheim and a Fulbright, a Director’s Fellow at the Center for Scholars and Writers at the New York Public Library, Prose is a former president of PEN American Center, and a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. She is a Distinguished Writer in Residence at Bard College.