Francine Prose: It's Harder Than It Looks to Write Clearly

Ask Yourself, Would I Say This?

It’s old-fashioned but helpful to have a basic command of grammar, of the rules and conventions that help make language clear. It has always seemed amazing to me that so few people learn grammar and so many learn to drive, which is so much harder, scarier, and more demanding! Grammar—parts of speech, subject-verb agreement, what follows a comma—makes life easier for the reader; words fall into a kind of order so that there is need to go scrambling back through the sentence to figure out what everything means and what describes what.

Unlike most other subjects, grammar is one of those things you can study and forget about and still know. Many middle-schoolers of my generation learned to diagram sentences, to break up a sentence into words we arranged on an odd little armature of lines, arrows, hooks, and chutes. I no longer need to do that to read a sentence and make the first of the decisions (subject? verb?) that would have directed where I wrote the words on the diagram. A minimal knowledge of grammar lets you understand the most complex sentence, or to write your own and be reasonably certain that it is clear.

No one wrote more clearly than Virginia Woolf did, in her essays, which, if we read them slowly enough, make perfect sense. But in case we find ourselves tripping over the long and lushly forested paths that her sentences lead us down, grammar gives us something—a sort of guide rail—to hold onto as we confront the product of a mind easily capable of skipping around and keeping several subjects and verbs (to say nothing of ideas) in play at once.

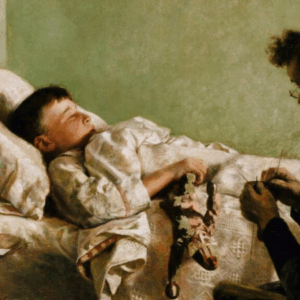

Here, for example, is a sentence from Woolf’s perceptive, beautiful, and comically ambivalent tribute to the invalid poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning, in a passage from an essay entitled “Poets’ Letters”: “The vigour with which she threw herself into the only life that was free to her and lived so steadily and strongly in her books that her days were full of purpose and character would be pathetic did it not impress us as with the strength that underlay her ardent and sometimes febrile temperament.” It takes each of us more or less time to figure out that it’s the vigour that would be pathetic, with a lifetime in between. The sooner we figure that out, the sooner we get the sentence. The rapid switching back and forth between admiring and critical adjectives and adverbs (steadily, strongly, pathetic, ardent, febrile) is itself a key to the range of Woolf’s responses, now generous, now judgmental. Her views alternate through these two paragraphs on Elizabeth Barrett Browning, which are not only clear but exhilarating, thanks to Woolf’s elegant mix of the skeptical and respectful.

“Not only was she a very shrewd critic of others, but, pliant as she was in most matters, she could be almost obstinate when her literary independence was attacked. The many critics who objected to faults of obscurity or technique in her writing she answered indeed, but answered authoritatively, as a person stating a fact, and not pleading a case. ‘my poetry,’ she writes to Ruskin, ‘which you once called “sickly” . . . has been called by much harder names, “affected”, for instance, a charge I have never deserved, if I may say it of myself, that the desire or speaking or spluttering the real truth out broadly, may be a cause of a good deal of what is called in me careless or awkward expression.’

“The desire was so honest and valiant that the ‘splutterer’ may be condoned, although there seems to be no reason to agree with Mrs. Browning in her tacit assertion that the cause of truth would be demeaned by a more scrupulous regard for literary form.”

Attentive readers will notice that while we know what Woolf is saying, sentence by sentence, her opinion of Elizabeth Barrett Browning is mixed; she thinks several things at once. She considers her at once admirable and irritating, heroic and at best a minor a poet. Also we may notice that Woolf, employing all those adjectives, is doing precisely what Chekhov told Gorky not to do. But so what? The end result is the same. You can open a volume of Woolf’s essays, like one of Chekhov’s stories, and not only follow what she is saying but find the sort of marvels produced when clarity of expression is combined with the intelligence, imagination, and ability to look at the world and tell us what she observes, which is always just a little more than we do.

Here is another passage from Woolf, that I particularly like, in which—in a 1908 essay entitled “Chateau and Country Life”—she offers us a new way to view the familiar pleasures of train travel:

Their comfort, to begin with, sets the mind free, and their speed is the speed of lyric poetry, inarticulate as yet, sweeping rhythm through the brain, regularly, like the wash of great waves. Little fragments of print, picked up by an effort from the book you read, become gigantic, enfolding the earth and disclosing the truth of the scene. The towns you see then are tragic, like the faces of people turned toward you in deep emotion, and the fields with their cottages have profound significance; you imagine the rooms astir and hear the cinders falling on the hearth and the little animals rustling and pausing in the woods.

*

For those who don’t want to learn grammar, who don’t want to apply its rules, and who don’t feel they have the time to read the Latin and Greek classics in the original like the Founding Fathers, an alternate route to clarity, which initially may seem like a shortcut but ultimately demand more practice and effort than learning grammar, is to somehow develop an ear for the clear sentence. There are people who can read a sentence or hear it in their heads, and more or less instantly know that it is, or isn’t, clear. When it isn’t, something seems wrong; an off note has been sounded. Everyone who speaks has felt this. What you said wasn’t what you meant to say. Your meaning wasn’t clear. Like an ear for music, an ear for clarity is a mysterious talent.

If I knew more about music, or the neurology of music, I would probably know better than to suggest that clarity of language stimulates the same cerebral pleasure points as the charming and beautiful piano pieces that Bach wrote for his wife Anna Magdalena, compositions that many beginning music students learn on their way to something requiring more technical skill. Clarity of language is not the St. Matthew Passion. It is the fact that the singers can say all the words and hit all the notes. It is not an end in itself but a means to an end. Which is not to say that clarity is not a beautiful thing.

Here are the clear and beautiful first lines of four of Charles Dickens’s novels.

David Copperfield: “Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show.”

Dombey and Son: “Dombey sat in the corner of the darkened room in the great arm-chair by the bedside, and Son lay tucked up warm in a little basket bedstead, carefully disposed on a low settee immediately in front of the fire and close to it, as if his constitution were analogue to that of a muffin, and it was essential toast him brown while he was very new.”

Nicholas Nickleby: “There once lived, in a sequestered part of the county of Devonshire, one Mr. Godfrey Nickleby: a worthy gentleman, who, taking it into his head rather late in life that he must get married, and not being young enough or rich enough to aspire to the hand of a lady of fortune, had wedded an old flame out of mere attachment, who in her turn had taken him for the same reason.”

Our Mutual Friend: “In these times of ours, though concerning the exact year there is no need to be precise, a boat of dirty and disreputable appearance, with two figures in it, floated on the Thames, between Southwark bridge which is of iron, and London Bridge which is of stone, as an autumn evening was closing in.”

“Whether you run a passage of writing through the checklist of grammar or put it to the test of the ear, clarity requires attentiveness to each sentence.”

Here are four opening sentences from the (certainly compared to Dickens) lesser known British novelist Barbara Comyns, most of whose books were first published during the 1950s:

The Vet’s Daughter: “A man with small eyes and a ginger moustache came and spoke to me when I was thinking of something else.”

Sisters by a River: “It was in the middle of a snowstorm I was born, Palmer’s brother’s wedding night, Palmer went to the wedding and got snowbound, and when he arrived very late in the morning he had to bury my packing under the walnut tree, he always had to do this when we were born—six times in all, and none of us died.”

Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead: “The ducks swam through the drawing room windows.”

Our Spoons Came from Woolworth’s: “I told Helen my story and she went home and cried.”

And here, occupying a sort of middle ground of complexity and length are three sentences, each of which appears at the start of one of Mark Twain’s essays. There is also the wry, seemingly rambling but in fact controlled and modulated sentence that follows the last of the three beginnings:

“Fenimore Cooper’s Literary Offenses”: It seems to me that it was far from right for the Professor of English Literature in Yale, the Professor of English literature in Columbia, and Wilkie Collins to deliver opinions on Cooper’s literature without having read some of it.”

It’s the “some of,” the “some of it” that makes the sentence great.

“Extracts from “Adam’s Diary.” “Monday.—this new creature with the long hair is a good deal in the way.” You have to know who Adam and Eve are, but many people still do.

“A Petition to the Queen of England”: “Madam: You will remember that last May Mr. Edgar Bright, the clerk of the Inland Revnue office, wrote me about a tax which he said was due from me to the government on books of mine. I do not know Mr. Bright, and it is embarrassing to me to correspond with strangers; for I was raised in the country and have always lived there, the early part in Marion County, Missouri, before the war, and this part in Hartford County, Connecticut, near Bloomfield, and about eight miles this side of Farmington, though some call it nine, which it is impossible to be, for I have walked it many and many as time in considerably under three hours, and General Hawley says he has done it in two and a quarter, which is not likely; so it seemed best that I write your Majesty.”

Does anything need to be said about the feet-shuffling country boy ramble with which we intuit, Twain will be asking not to be taxed on the royalties for his books?

What all these sentences have in common is that they are carefully put together, transparent and deep, complete in themselves yet suggestive of a promise: new information is still to come, in the sentences that will follow.

*

Whether you run a passage of writing through the checklist of grammar or put it to the test of the ear, clarity requires attentiveness to each sentence. It demands the time, the energy, and the patience needed to ask if the sentence is clear. Then fiddling with it until it is. Is it clear now? What about now? Unless you are one of those magical beings who gets it right the first time, so that language fountains out of you, burbling transparent music.

It is actually very hard to write an unintelligible sentence on purpose—as Chekhov has already demonstrated—and no one plans to do that. At least very few people do once they are out of their teens, when they half hope that every communication could be coded in a language that only a select few (or sometimes just the author) can decipher. Writers want to be understood, even if the writer is Faulkner, pouring on the phrase after phrase into the Southen gothic rants that go on for pages of Absalom, Absalom; even if the writer is James Joyce, composing the soliloquy at the end of Ulysses, which also rattles on for pages, ranging through time and geography, through experience and fantasy, opinion, sex, rumination, delivering specific information about what Molly Bloom is saying and also more general observations (embedded in the text) about the way in which memory and consciousness function.

Just to complicate things further, I’ll mention one of my favorite sentences, a sentence that takes the kind of sentence Chekhov advised Gorky to write (“The sun shone”) and adds a few carefully chosen words so that it stays completely clear and at the same time goes completely crazy.

That is the famous first sentence of Samuel Beckett’s first novel, Murphy:

“The sun shone, having no alternative, on the nothing new.”

We get the sunshine and at the same time the fact that the voice that is speaking to us is hilariously sour and possibly quite far out on the raw edges of human existence.

In one sentence Beckett gives us Chekhov, Camus, and a dope slap. For Beckett, adding those few words shows the reader the same scene (sunshine) and sharpens the focus, like the lens on an old-fashioned camera, reaching beyond the sunshine to Murphy, who has tied himself to a rocking chair and is rocking and rocking and rocking to ward off the anxiety of being dispossessed from a home where he isn’t any more or less happy than he was in his last home, or will be in the next.

Beckett isn’t the easiest writer to understand. Nor did he mean to be. One feels that it would have enraged him to be told to slow down and make sure we are keeping up. But there are moments like this one, instances when he is dazzlingly lucid, giving us the weather report and, with just a few words, shining a high intensity beam on a universal but understandably underexplored corner of the human psyche.

Having no alternative. On the nothing new. Nothing could be clearer, more mysterious, or thrilling. If a sentence is a tightrope from one pole to another, Beckett’s sentences are test-dummy rides, slamming his readers into the wall of a perpetual three o’clock in the morning. Though Beckett might be surprised to hear it, the amount and the quality of the information communicated in Murphy’s opening sentence recall something that Virginia Woolf—one of the publishers of the press that Beckett called the Hogarth Private Lunatic Asylum—wrote at the conclusion of the essay, “Chateau and Country Life,” the piece that begins with her description of the pleasures of train travel:

“There is a reason to be grateful when anyone writes very simply, both for the sake of the things that are said, and because the writer reveals so much of her own character in her words.”

Like Beckett’s sentence, Woolf’s presupposes that there is such a thing as character, and that we might be interested in it, and that, if we are talking about such complicated subjects as character, it is important to be clear.

Francine Prose

Francine Prose is the author of twenty-two works of fiction including the highly acclaimed The Vixen; Mister Monkey; the New York Times bestseller Lovers at the Chameleon Club, Paris 1932; A Changed Man, which won the Dayton Literary Peace Prize; and Blue Angel, which was a finalist for the National Book Award. Her works of nonfiction include the highly praised Anne Frank: The Book, The Life, The Afterlife, and the New York Times bestseller Reading Like a Writer, which has become a classic. The recipient of numerous grants and honors, including a Guggenheim and a Fulbright, a Director’s Fellow at the Center for Scholars and Writers at the New York Public Library, Prose is a former president of PEN American Center, and a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. She is a Distinguished Writer in Residence at Bard College.