Four Theories Toward the Timeless Brilliance of Infinite Jest

Tom Bissell on the Novel of Its Generation

Something happens to a novel as it ages, but what? It doesn’t ripen or deepen in the manner of cheese and wine, and it doesn’t fall apart, at least not figuratively. Fiction has no half-life. We age alongside the novels we’ve read, and only one of us is actively deteriorating.

Which is to say that a novel is perishable only by virtue of being stored in such a leaky cask: our heads. With just a few years’ passage, a novel can thus seem “dated,” or “irrelevant,” or (God help us) “problematic.” When a novel survives this strange process, and gets reissued in a handsome twentieth-anniversary edition, it’s tempting to hold it up and say, “It withstood the test of time.” Most would intend such a statement as praise, but is a twenty-year-old novel successful merely because it seems cleverly predictive or contains scenarios that feel “relevant” to later audiences? If that were the mark of enduring fiction, Philip K. Dick would be the greatest novelist of all time.

David Foster Wallace understood the paradox of attempting to write fiction that spoke to posterity and a contemporary audience simultaneously, with equal force. In an essay written while he was at work on Infinite Jest, Wallace referred to the “oracular foresight” of a writer he idolized, Don DeLillo, whose best novels—White Noise, Libra, Underworld—address their contemporary audience like a shouting desert prophet while laying out for posterity the coldly amused analysis of some long-dead professor emeritus.

Wallace felt that the “mimetic deployment of pop-culture icons” by writers who lacked DeLillo’s observational powers “compromises fiction’s seriousness by dating it out of the Platonic Always where it ought to reside.” Yet Infinite Jest rarely seems as though it resides within this Platonic Always, which Wallace rejected in any event. (As with many of Wallace’s more manifesto-ish proclamations, he was not planting a flag so much as secretly burning one.) We are now half a decade beyond the years Wallace intended Infinite Jest’s subsidized time schema—Year of the Whopper, Year of the Depend Adult Undergarment—to represent. Read today, the book’s intellectually slapstick vision of corporatism run amok embeds it within the early to mid-1990s as firmly and emblematically as The Simpsons and grunge music. It is very much a novel of its time.

How is it, then, that Infinite Jest still feels so transcendently, electrically alive?

Theory one: as a novel about an “entertainment” weaponized to enslave and destroy all who look upon it, Infinite Jest is the first great Internet novel. Yes, William Gibson and Neal Stephenson may have gotten there first with Neuromancer and Snow Crash, whose Matrix and Metaverse, respectively, more accurately surmised what the Internet would look and feel like. (Wallace, among other things, failed to anticipate the break from cartridge-and disc-based entertainment.) But Infinite Jest warned against the insidious virality of popular entertainment long before anyone but the most Delphic philosophers of technology. Sharing videos, binge-watching Netflix, the resultant neuro-pudding at the end of an epic gaming marathon, the perverse seduction of recording and devouring our most ordinary human thoughts on Facebook and Instagram—Wallace somehow knew all this was coming, and it gave him (as the man himself might have put it) the howling fantods.

In interviews, Wallace was explicit that art must have a higher purpose than mere entertainment, leading to his most famous and bellicose thought on the matter: “Fiction’s about what it is to be a fucking human being.” And here, really, is the enigma of David Foster Wallace’s work generally and Infinite Jest specifically: an endlessly, compulsively entertaining book that stingily withholds from readers the core pleasures of mainstream novelistic entertainment, among them a graspable central narrative line, identifiable movement through time, and any resolution of its quadrumvirate plotlines.

“Read today, the book’s slapstick version of corporatism run amok embeds it within the early to mid-1990s as firmly and emblematically as grunge music and The Simpsons.”

Infinite Jest, in other words, can be exceedingly frustrating. To fully understand what Wallace was up to, the book bears being read, and reread, with Talmudic focus and devotion. For many Wallace readers this is asking too much. For many Wallace fans this is asking too much. And thus the Wallace factions have formed—the Nonfictionites versus the Jestians versus the Short-Storyists—even though every faction recognizes the centrality of Infinite Jest to his body of work. The fact that twenty years have gone by and we still do not agree what this novel means, or what exactly it was trying to say, despite saying (seemingly) everything about everything, is yet another perfect analogy for the Internet. Both are too big. Both contain too much. Both welcome you in. Both push you away.

Theory two: Infinite Jest is a genuinely groundbreaking novel of language. Not even the masters of the high/low rhetorical register go higher more panoramically or lower more exuberantly than Wallace—not Joyce, not Bellow, not Amis. Aphonia, erumpent, Eliotical, Nuckslaughter, phalluctomy! Made-up words, hot-wired words, words found only in the footnotes of medical dictionaries, words usable only within the context of classical rhetoric, homechemistry words, mathematician words, philosopher words—Wallace spelunked the OED and fearlessly neologized, nouning verbs, verbing nouns, creating less a novel of language than a brand-new lexicographical reality.

But nerdlinger word mongering, or “stunt-pilotry” (to use another Wallace phrase), can be an empty practice indeed. You need sentences to display-case the words, and here, too, Infinite Jest surpasses almost every novel written in the last century, displaying a consistent and mind-boggling descriptive mastery, as when he describes a sunset as “swollen and perfectly round, and large, radiating knives of light. . . . It hung and trembled slightly like a viscous drop about to fall.” (No one is better than Wallace when it comes to skies and weather, which is traceable to his having grown up in central Illinois, a land of flat tornado-haunted vastidity.) As John Jeremiah Sullivan wrote after Wallace’s death, “Here’s a thing that is hard to imagine: being so inventive a writer that when you die, the language is impoverished.” It has been eight years since Wallace left us, and no one is refilling the coffers of the David Foster Wallace Federal Sentence Reserve. No one is writing anything that resembles this: “The second shift’s 1600h. siren down at Sundstrand Power & Light is creepily muffled by the no-sound of falling snow.” Or this: “But he was a gifted burglar, when he burgled—though the size of a young dinosaur, with a massive and almost perfectly square head he used to amuse his friends when drunk by letting them open and close elevator doors on.” We return to Wallace sentences now like medieval monks to scripture, tremblingly aware of their finite preciousness.

While I have never been able to get a handle on Wallace’s notion of spirituality, I think it is a mistake to view him as anything other than a religious writer. His religion, like many, was a religion of language. Whereas most religions deify only certain words, Wallace exalted all of them.

Theory three: Infinite Jest is a peerlessly gripping novel of character. Even very fine novelists struggle with character, because creating characters that are not just prismatic snap-off versions of oneself happens to be supremely difficult.

In How Fiction Works, the literary critic James Wood, whose respectful but ultimately cool view of Wallace’s work is as baffling as Conrad’s rejection of Melville and Nabokov’s dismissal of Bellow, addresses E. M. Forster’s famous distinction between “flat” and “round” characters: “If I try to distinguish between major and minor characters—flat and round characters—and claim that these differ in terms of subtlety, depth, time allowed on the page, I must concede that many so-called flat characters seem more alive to me, and more interesting as human studies, than the round characters they are supposedly subservient to.” Anyone reading or rereading Infinite Jest will notice an interesting pertinence: throughout the book, Wallace’s flat, minor, one-note characters walk as tall as anyone, peacocks of diverse idiosyncrasy. Wallace doesn’t simply set a scene and novelize his characters into facile life; rather, he makes an almost metaphysical commitment to see reality through their eyes.

A fine example of this occurs early in Infinite Jest, during its “Where was the woman who said she’d come” interlude. In it we encounter the paranoid weed addict Ken Erdedy, whose terror of being considered a too-eager drug buyer has engendered an unwelcome situation: he is unsure whether or not he actually managed to make an appointment with a woman able to access two hundred grams of “unusually good” marijuana, which he very much wants to spend the weekend smoking. For eleven pages, Erdedy does nothing but sweat and anticipate this woman’s increasingly conjectural arrival with his desired two hundred grams. I suspect no one who has struggled with substance addiction can read this passage without squirming, gasping, or weeping. I know of nothing else in the entirety of literature that so convincingly inhabits a drug-smashed consciousness while remaining a model of empathetic clarity.

“He trains you to study the real world through the lens of his prose.”

The literary craftsman’s term for what Wallace is doing within the Erdedy interlude is free indirect style, but while reading Wallace you get the feeling that bloodless matters of craftsmanship rather bored him. Instead, he had to somehow psychically become his characters, which is surely why he wrote so often, and so well, in a microscopically close third person. In this very specific sense, Wallace may be the closest thing to a method actor in American literature, which I cannot imagine was without its subtle traumas. And Erdedy is merely one of Infinite Jest’s hundreds of differently damaged walk-on characters! Sometimes I wonder: What did it cost Wallace to create him?

Theory four: Infinite Jest is unquestionably the novel of its generation. As a member (barely) of the generation Wallace was part of, and as a writer whose closest friends are writers (most of whom are Wallace fans), and as someone who first read Infinite Jest at perhaps the perfect age (twenty-two, as a Peace Corps volunteer in Uzbekistan), my testimony on this point may well be riddled with partisanship. So allow me to drop the mask of the introducer to show the homely face of a fan, and much later a friend, of David Wallace.

As I read Infinite Jest in the dark early mornings before my Uzbek language class, I could hear my host-mother talking to the chickens in the barn on the other side of my bedroom wall as she flung scatters of feed before them. I could hear the cows stirring, and then their deep, monstrous mooing, along with the compound’s approximately ten thousand feral cats moving in the crawl space directly above my bed. What I am trying to say is that it should have been difficult to focus on the doings of Hal Incandenza, Don Gately, Rémy Marathe, and Madame Psychosis. But it wasn’t. I read for hours that way, morning after morning, my mind awhirl. For the first few hundred pages of my initial reading, I will confess that I greatly disliked Infinite Jest. Why? Jealousy, frustration, impatience. It’s hard to remember exactly why. It wasn’t until I was writing letters to my girlfriend, and describing to her my fellow Peace Corps volunteers and host-family members and long walks home through old Soviet collectivized farmland in what I would categorize as yellow-belt Wallaceian prose, that I realized how completely the book had rewired me. Here is one of the great Wallace innovations: the revelatory power of freakishly thorough noticing, of corralling and controlling detail. Most great prose writers make the real world seem realer—it’s why we read great prose writers. But Wallace does something weirder, something more astounding: even when you’re not reading him, he trains you to study the real world through the lens of his prose. Several writers’ names have become adjectivized—Kafkaesque, Orwellian, Dickensian—but these are designators of mood, of situation, of civic decay. The Wallaceian is not a description of something external; it describes something that happens ecstatically within, a state of apprehension (in both senses) and understanding. He didn’t name a condition, in other words. He created one.

As I learned—as Wallace’s eager imitators learned—as Wallace himself learned—there were limits to the initially limitless-seeming style Wallace helped pioneer in Infinite Jest. All great stylists eventually become prisoners of their style and, in a final indignity, find themselves locked up with their acolytes. Wallace avoided this fate. For one, he never finished another novel. For two, he created ever more space between the halves of his career—the friendly, coruscating essayist and the difficult, hermetically inclined fiction writer—so that, eventually, there was little to connect them. Another way of saying this is that the essays got better and funnier—the funniest since Twain—while the fiction got darker and more theoretically severe, even if so much of it was excellent.

The last time I saw David Wallace, in the spring of 2008, he successfully affected artistic contentment, which I now know was the antipode of his true feelings. Nevertheless, I came away from our encounter excited about the work that was to come, which he’d briefly alluded to. He’d given us one novel of generational significance; surely he’d write the novel that helped us define what the next century would feel like. Our great loss is that he didn’t. His great gift is that the world remains as Wallaceian as ever—Donald Trump, meet President Johnny Gentle—and now we’re all reading his unwritten books in our heads.

David, where be your gibes now? Your gambols, your songs—your flashes of merriment that were wont to set the table on a roar? They’re here, where they’ve always been. Will always be. You have borne us on your back a thousand times. For you, and this joyful, despairing book, we will roar forever amazed, forever sorrowful, forever grateful. I hope against hope you can hear us.

–2016

__________________________________

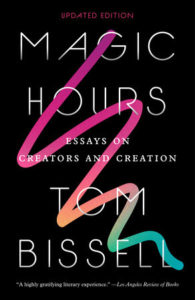

From Magic Hours: Essays on Creators and Creation. Used with permission of Vintage. Copyright © 2018 by Tom Bissell. This essay first appeared in the New York Times.