Forgiving the Unforgivable: Geronimo's Descendants Seek to Salve Generational Trauma

Traveling to the Heart of Mexico for a Ceremonia del Perdón

1.

OKLAHOMA TO TEXAS

On a Monday in early August I find myself spooning soil from Geronimo’s grave at a prisoner of war cemetery in Oklahoma into a double ziplock bag I bought at Target. I will carry this soil, by car and bus, to Guachochi, a provincial Mexican town in the Sierra Madre Occidental. There, three Mexican sisters who recently traced their ancestry to this famous Apache medicine man are about to hold a Ceremonia del Perdón—a Ceremony of Forgiveness. The soil is my gift to them.

Geronimo’s grave is inside Fort Sill, a US army base, so I must first stop at the visitor center to obtain a pass. The United States staked out Fort Sill in 1869, as a staging ground for punitive raids against the Native Americans who had survived deportation to Indian Territory, but its visitor center bears the ubiquitous hallmarks of US military efficiency that scream temporariness: insulated white metal wall panels mounted on a concrete foundation and facing a parking lot paved with ankle-breaker gravel. I have seen structures and parking lots exactly like this on American bases in Iraq and Afghanistan; I imagine many of those are now gone. Inside the visitor center, a jovial military policeman hands me a Form 118a, Request for Unescorted Installation Access to Fort Sill. This is to ensure I am not a terrorist. I enter my full name, date of birth, driver’s license number, social security number, gender, race. Under “purpose of visit” I check “other.”

The Beef Creek Apache Cemetery was established in 1894, the year Geronimo and a band of 341 other surrendered Chiricahua Apaches were transferred from a prisoner of war camp in Florida to Fort Sill under military escort. Here, in the foothills of the Wichita Mountains, the Apache man’s campaign against white colonists came to an end. It had begun in 1851, when Mexican soldiers massacred more than a hundred women and children in Geronimo’s encampment, among them his mother, his first wife, and all three of his young children.

At Beef Creek, rows of identical upright headstones of white marble poke out of a manicured sloping field of green; think Arlington Cemetery minus the color guard. Among this impersonal personal misery, Geronimo’s tomb is a pyramid of granite boulders about five feet tall topped with a stone eagle. A small grove of white hibiscus and fragrant abelia sets it slightly apart from the rest of the graveyard.

Before I knelt to scrape topsoil from the grave, it had been desecrated at least twice. Less than a decade after Geronimo died in 1909, of pneumonia but ultimately of humiliation and drink that followed his imprisonment, members of Yale’s Skull and Bones—among them, allegedly, Prescott Bush, grandfather of President George W. Bush—dug up his corpse, cut off his head, and brought the skull to the society’s headquarters in New Haven. A hundred years after his death, Geronimo’s descendants in the United States lost a federal suit to repatriate the skull under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990. Since that ruling, I now see, someone has beheaded the stone eagle on the tomb.

“They caged him, they debauched his dignity, they chopped off his head. They put an eagle on his grave and chopped off its head, too.”

What was it like to be a POW of the United States back then? Different than Guantanamo: the Apache prisoners could set up villages within the perimeter of the army base. They could marry and raise children. Or watch them die: many headstones have only one date (stillborn? dead of fright at being born in prison?). One couple lost three children in five years.

Some Apache got to travel outside the wire. With Pawnee Bill’s Wild West Show, which advertised his cameo as “The Worst Indian That Ever Lived,” Geronimo hawked his legend at county fairs. And he was one of six indigenous men to ride horseback in Teddy Roosevelt’s inaugural parade through the streets of Washington in 1901. When Roosevelt was asked why he chose this “greatest single-handed murderer in American history” to join his parade, the president replied: “I wanted to give the people a good show.”

To the left of Geronimo’s is the grave of the sixth of his nine wives, Zi-Yeh, who died in 1904 at the age of 35, of tuberculosis. To the right, the grave of their daughter Eva Geronimo Godeley, who was forced to attend one of the Indian boarding schools the US government had created to assimilate native children and strip them of their roots; her school was almost 200 miles away. She was 21 when she died, in 1911. Eva’s daughter, Evaline, died at birth the year previous; she is buried here, too. Geronimo was gone by then: in February of 1909 he was riding home drunk after selling bows and arrows at Lawton, Oklahoma when he fell off a horse and was too hurt or too drunk to stand. He spent the night in biting winter cold before a friend found him ill the next morning. He died three days later.

![]()

It is noon. Thunderclouds are building in Oklahoma’s sticky midsummer heat. I am alone at the cemetery; I take my time. The last grave I visit belongs to a medicine woman. Her name was Id-Is-Tah-Nah. Mexican troops kidnapped her from Geronimo’s camp when she was a teenager and sold her into slavery to a maguey planter, who renamed her Francisca. Several years later she ran away and, after many days on foot, reunited with her kin. On the way a mountain lion attacked her and disfigured her terribly. Geronimo took her as his seventh wife. She danced beautifully.

Her headstone tells us none of this. It bears only one name, “Francisco,” and under it the words “Apache woman” and two dates. This is all she was to them. This is all they want us to remember. I feel turned inside out. I begin to bawl.

I drove here from Tulsa, where I am doing an art fellowship on the grounds of the deadliest massacre of black Americans in the US history. Here, in late spring of 1921, a white mob torched a prosperous African-American neighborhood called Greenwood, also known as Black Wall Street. Armed white men gunned down Greenwood residents in the streets. Some accounts tell of police planes firebombing the neighborhood from the air. Several hundred black people were murdered in that holocaust, 6,000 were thrown in impromptu detention, and 10,000 were left homeless. Around that time, on an Osage reservation just north of the city, a conspiracy of white men murdered Native American landowners for oil wealth.

Two months before Fort Sill I began to document the swastikas I encountered in town. Two necklaces arranged in the shape of a swastika on a shelf of a souvenir shop. Two swastikas spray painted next to a playground by the Arkansas River, where I run some mornings. Another swastika spray painted on the bike path just north of my ob-gyn’s office in North Tulsa, the neighborhood to which the survivors of what is now remembered as the Tulsa Race Massacre were evicted and where their descendants now live, priced out of Greenwood by gentrification.

I play a role in that gentrification. Artists make real estate more attractive, therefore more expensive: I am a tool of erasure. Hipsters are moving into my section of Greenwood, which today bears the name of a local Klansman: the Brady Arts District. The window next to my writing desk looks out at a concentration camp where survivors of the massacre were interned for days. It is now a music venue, the Brady Theater, named after the same Klansman; Nora Jones performed one night. The bakery across the street from my flat is called Antoinette’s and a sign in one of the windows reads “Eat Cake.” Talk about beheaded cemetery eagles. This is not tone-deafness; this is an insult.

All of these insidious moral crises coalesce on this first stop on my journey to the Ceremony of Forgiveness. I think of what James Baldwin called the “guilty and constricted white imagination,” an imagination that does not allow for a world in which white man is not king. A paralytic fear of a powerful Other that enabled the Middle Passage, Hitler, the systemic annihilation of indigenous Americans. The fear that made possible the pogrom of Black Wall Street on whose charnel ground I now live and write.

Today it dictates the abiding neo-colonialism that continues to shape the world in which old protectorates have been replaced by client states, subservient to the wants of the Global North. It dislocates empathy and fences out migrants. It is the root of the racist violence in Charlottesville, Virginia, where fascist thugs will riot in the name of white supremacy on the very day my hosts in the Sierra Madre, 3,000 miles away, wish their sorrow turn to ash and smoke in a ceremonial fire.

And it simmers here, with Geronimo. They caged him, they debauched his dignity, they chopped off his head. They put an eagle on his grave and chopped off its head, too. Such is the magnitude of their fear. Such is the scope of their hate. The air grows heavy with cloud.

I weep all the way from Fort Sill to the Texas-Mexico border. I keep the ziplock bag with cemetery dirt in my lap. From the road I message Roberto Lujan, a retired teacher who grows pomegranate trees in Presidio, Texas, just across the Rio Grande from Mexico. Roberto is Jumano Apache; we met when I lived in the area for several months, before Tulsa. It was he who invited me to the ceremony because he knows that I am working on a novel about genocide and identity set on the border. We will travel from Presidio to Guachochi together. Roberto throws me a line to hold on to: “The scars in our hearts will cauterize in the strong womb of the Sierra Madre.” But I cannot let go of a different line, by Zbigniew Herbert: “and do not forgive truly it is not in your power / to forgive in the name of those betrayed at dawn.”

2.

TEXAS TO MEXICO

Two days later, Roberto, our photographer friend Jessica Lutz, and I cross the border bridge from Presidio to Ojinaga. The Rio Grande runs fat and brown under the bridge. Her power is metaphysical, her thalweg, the deepest part of her watercourse, is a frontier between two worlds that ooze chance and desire and suspicion and pity. When the Mexican immigration agent asks where we are headed, Roberto says: “To a celebration.” He is giddy. I think: despite the fear and the hatred something has begun to uncoil—in ceremonies like the one to which we are headed; in the momentum in native activism post-Standing Rock.

We take a bus from Ojinaga to Chihuahua City. The symbol of the bus company is a sprinting rabbit with bright red ears, a calque of the Greyhound dog. The TV screen above the windshield is playing Unbroken, Angelina Jolie’s disturbing film about American prisoners of war in Japan during the second World War, dubbed into Spanish, and a lady across the aisle is reading the Dale Carnegie classic, Cómo Ganar Amigos e Influir Sobre las Personas. The desert, Technicolor green after recent rains, rolls past my window. Somewhere in it, the bones of the victims of narco massacres pave over the bones of the victims of conquistadors’ gold fever missions. For half a millennia, violence in this land has been fueled by white man’s addictions.

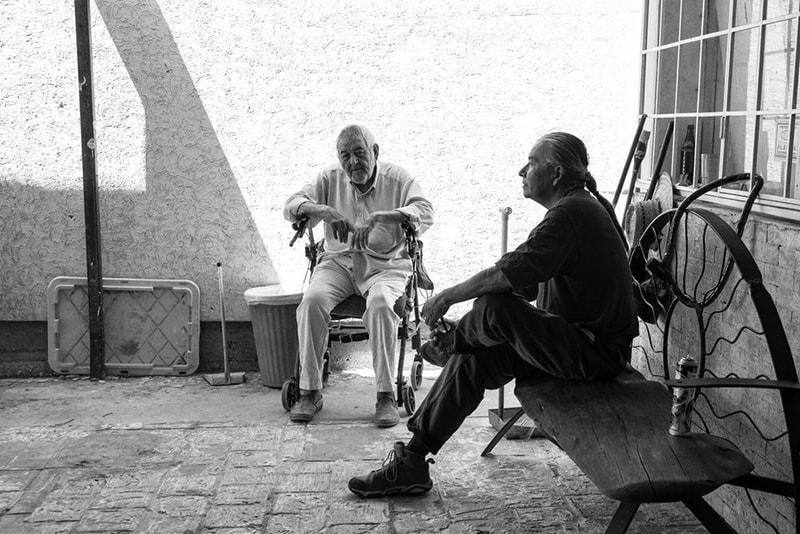

Lipan Apache Roberto Lujan of Presidio Texas (right) rests on a bench in Chihuahua City before the long ride to Guachochi, Mexico where the ceremony was held. Lujan helped organize several Apache Gathering events, the first of which took place in Ojinaga Mexico earlier this year. Photo by Jessica Lutz / IWMF Fellow for the Adelante Latin American Reporting Initiative.

Lipan Apache Roberto Lujan of Presidio Texas (right) rests on a bench in Chihuahua City before the long ride to Guachochi, Mexico where the ceremony was held. Lujan helped organize several Apache Gathering events, the first of which took place in Ojinaga Mexico earlier this year. Photo by Jessica Lutz / IWMF Fellow for the Adelante Latin American Reporting Initiative.

I tell Roberto about the beheaded eagle on Geronimo’s tombstone.

“I don’t get it,” I say.

“We’re not supposed to get it,” he says. “We are supposed to move beyond it. That’s why we’re going to the Sierra Madre. We are going so we can move beyond it.”

In the luggage compartment in the belly of the bus rocks the soil from Geronimo’s grave.

3.

CHIHUAHUA CITY

Under puffy clouds the Chihuahuan Desert stretches and stretches on south, the grass startlingly tall after all the rains, and the ancient volcanoes in the distance stand blue and indifferent in the high noon sun. The bus chugs past roadside salesmen who thrust at the traffic ice cream on a stick, peeled mango slices, peanuts, horse saddles.

My geographical journey from Oklahoma to Guachochi mimics, in a way, the southward passage of Apaches, after a succession of colonists drove them from their ancestral lands in the prairie to the Rio Grande and across, massacring them and disarming and penning into reservations the survivors, chasing them southward across the desert and up to clouds’ rim at 8,000 feet.

Theirs was a quest for safety. The quest of my Guachochi hosts is one family’s gentle effort to overcome generational trauma. Mine? I am trying to learn what forgiveness is and whether it is possible.

We stop in Chihuahua City for the night. Monsoons in the mountains have washed out the faster road to Guachochi and we will need a full day to reach the town. Today is the International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples, and the government of Chihuahua is sponsoring a free concert of Rarámuri folk artists in the main square, between the cathedral and the government palace. We gorge on the spinning color of the women’s full skirts. How long, I wonder out loud, before the government of Texas sponsors an Apache concert on state Capitol grounds in Austin?

“Exactly,” says Roberto.

“The quest of my Guachochi hosts is one family’s gentle effort to overcome generational trauma. Mine? I am trying to learn what forgiveness is and whether it is possible.”

By sunset the downtown is full of people. I don’t see any foreign tourists. Most are local families with children and couples shopping or eating out, stopping to watch the folk concert, listen to mariachi bands, buy ice cream or elotes. The last city census, in 2013, counted almost 900,000 inhabitants. Now, I am told, the population is swelled to over a million people, mostly by migrants: rural folk seeking work in the metroplex, victims of the Trump administration’s fear-driven mass-deportation agenda, and increasingly desperate Central Americans willing to risk the crossing, like the young man I see on a median holding up a piece of cardboard that reads: “Soy de Nicaragua. Ayúdame por el amor de dios.” The “N” in Nicaragua is written backward.

As evening falls I notice another presence downtown: soldiers in camouflage on flatbed trucks with mounted machine guns. Now they are parked by the government palace. Now they are driving at a crawl past my hotel. Now they are lost among the many taillights of a weeknight. Cartel turf wars are ravaging Mexico, especially her indigenous communities. The soldiers: another reminder of the accretion of pain.

4.

SIERRA MADRE

Bernarda Holguín Gámez is medium tall, in her early sixties. She is a retired civil servant at Mexico’s now-defunct Secretariat of Agrarian Reform, a sometime tour operator, and the senior of the Holguín sisters. A photo of her as a 17-year-old shows a lean girl, her shoulder-length dark hair down, a string of beads around her neck. She still wears bead necklaces, her hair, now much longer, down or in a braid that is mostly gray. She hugs eagerly; all the Holguíns do. She wraps me in a bear hug the first time we meet. Her voice is assertive and calm, yet even when she speaks in public it conveys great tenderness. As if she is grateful to you for being here, by her side. She ends most conversations with a “God bless you” and “God bless your family.”

Several years ago, a friend in the United States pointed out the resemblance between Bernarda’s second son Jesús and Geronimo. Bernarda and her youngest sister, Gina, started looking at pictures. It was true: Jesús did look like Geronimo. So did their father. So did their paternal uncle. A lot.

The likeness made them doubt the family story that the Holguíns had descended from a French grandmother. They began to question their parents’ honesty. Unsettled, Bernarda sought therapy; the counselor suggested she was suffering from generational trauma. Her cholesterol skyrocketed. She went on medication. Then, for two years, she went blind.

This may be the stuff of allegories, of parables.

This may be an appropriate response to the maggoty underbelly of deception that belies North America’s modern creation story.

What the sisters found after Bernarda’s vision returned, and they focused on family lineage in earnest, was no French connection. Instead, poring over birth records, marriage licenses and death certificates across five Mexican states, they uncovered a genealogy that packs the continent’s post-Columbian history of exploitation, racial violence, and shame into a tale of a hundred-plus years of cruelty and denial.

Loera “Hillary” Holguín, Bernarda’s 16-year-old daughter, juxtaposed with a painting of Virgin Mary hanging on a wall of the adobe house where the Holguín sisters were raised. Photo by Jessica Lutz / IWMF Fellow for the Adelante Latin American Reporting Initiative.

Loera “Hillary” Holguín, Bernarda’s 16-year-old daughter, juxtaposed with a painting of Virgin Mary hanging on a wall of the adobe house where the Holguín sisters were raised. Photo by Jessica Lutz / IWMF Fellow for the Adelante Latin American Reporting Initiative.

April 1882. Mexican troops wait until most men leave Geronimo’s camp at Alisos Creek, then storm the camp. They bayonette and shoot at point blank 78 people, mostly women and children. They take captive 33 others, and drive them to the stockade in Chihuahua City. Among their spoils are Geronimo’s second wife, Chee-Hash-Kish; their son Casimiro; their married daughter, Tah-Nah-Nah “Victoriana” Díaz García; and Victoriana’s firstborn, a boy. Victoriana is pregnant with her second child, a girl, who will be born in prison.

Victoriana’s husband, a gringo named Zebina Nathaniel Streeter, eventually negotiates the release of his wife, their two children, and, possibly, Chee-Hash-Kish and Casimiro. The family escapes to the Sierra Madre, where they live in hiding. By June 1889, both the US and Mexican governments have put a bounty on Streeter’s head for helping Apache insurgents. Then someone leaves a note on the desk of an Arizona newspaper. Streeter, the note says, was murdered by a lover.

Playing dead: a trick of a prey trying to escape a predator. A common tool among the Apaches who wanted to survive white man’s dragnet. Apache tradition says that speaking of the dead disturbs their eternal rest—and so, after Streeter’s pretend death, the family would never mention him. Soon, another man’s name begins to appear in public records in Streeter’s place: Juan Ramón Holguín, a rural rancher, the husband of Victoriana Díaz García. An Apache medicine man from Arizona would tell the sisters their last name, Holguín, means Someone Who Carries a Secret.

In 1901 Victoriana and Juan Ramón, né Streeter, have a son they name Primitivo Holguín Díaz. He is Bernarda’s father.

January 1883. Mexican troops raid Geronimo’s camp in Sonora, massacre seventeen people and kidnap 37. Among the prisoners are Geronimo’s fifth wife, Shtsh-She, and their daughter, Mariana Hernández, who is eight years old. The soldiers drive them to Chihuahua City, maybe to the same stockade as Chee-Hash-Kish and Victoriana. Geronimo tries to bargain for the prisoners’ release, but negotiations falter. By now, Mexican soldiers have killed two of his wives and four of his children, and a quarter of the entire United States’ army is hunting him in the longest counterinsurgency campaign in US history. Three years later, he gives up.

“For years I fought the white man thinking that with my few braves I could kill them all and that we would again have the land that our Great Father gave us and which he covered with game,” Geronimo would tell a reporter. “After I fought and lost and after I traveled over the country in which the white man lives and saw his cities and the work that he has done, my heart was ready to burst. I knew that the race of the Indian was run.”

Shtsh-She and Mariana are sold into slavery to Batopilas, a colonial outpost in the Sierra Madre, about eighty miles from Guachochi. On paper, the Spanish crown abolished Indian slavery in 1542; in reality, servitude—sometimes called debt peonage—proliferated as late as 1908, when a gringo journalist posing as a millionaire investor was offered an Indian laborer for 400 pesos. How much does their owner pay for Geronimo’s wife and daughter? What kind of work must they perform? Are they flogged, as is the custom? Are they raped?

Eventually, Shtsh-She and Mariana run away into the dim canyons and join other Apaches ghosting in tributary gorges and mountain caves. Mariana marries a Mexican colonel and renounces her Indian roots. In 1898, they have a daughter, Bernarda Hernández Ortiz. She is the Holguín sisters’ maternal grandmother. Bernarda bears her name.

In 1943, after the death of his first wife, Primitivo marries Soledad Gámez Hernández, the daughter of Bernarda Hernández Ortiz. Do they know that they are uncle and niece, several times removed? Is this why the Holguín family is plagued by an extraordinarily high incidence of ill health—lupus, structural birth defects, cancer, depression? Or are the illnesses conversion disorders caused by generational trauma, as Bernarda believes? The mountains hold so much concave silence. Primitivo and Soledad have eight children; Bernarda Holguín Gámez is the eldest daughter. Growing up among darker-skinned Rarámuri, the siblings are taught that they are white.

This weekend, the Holguíns are for the first time celebrating their lineage and honoring their roots in the very mountains where their ancestors denounced and hid theirs.

![]()

We arrive in Guachochi the night before the opening event. The mountains are drenched with recent rains; between outcrops of piñon, bald rock paths shine like a lattice of quicksilver. Our rental sedan barely negotiates the rain-slicked mountain curves on bald tires and two cylinders. At one point, after fording a river, it gets stuck on an unpaved upslope.

By the time we reach the Holguín ranch it is almost dark. The sister’s father built the ranch in 1924; they were born here. One of the sisters, Hilda, tells me their umbilical cords are buried somewhere in the garden. No one lives on the ranch year round anymore. There is occasional electricity and occasional running water. Tonight, lightning has knocked out power on the property and the pump is not working. In the kitchen, three gas lamps are lit. Hilda, who now lives mostly in Vancouver with her children, is telling me about growing up here—the two-hour-long hikes to school; the mushroom hunts. Two Rarámuri women are preparing refreshments: a vat of canela, sandwiches, sweet buns.

Hilda Holguín, left, bears a striking resemblance to her ancestor, Geronimo.

Hilda Holguín, left, bears a striking resemblance to her ancestor, Geronimo. Photo by Jessica Lutz / IWMF Fellow for the Adelante Latin American Reporting Initiative.

Outside it is raining again and more people have arrived in trucks. They move about the dark garden with cellphone flashlights on. Someone is building a fire. Someone is raising a tepee. Children and dogs chase one another in wet grass. I seek out Kiriaki Orpinel, a niece of the Holguín sisters, an anthropologist who champions human rights of traditional societies in the Sierra Madre. Kiriaki is Rarámuri on her father’s side, and, as she now knows, Apache on her mother’s. She is beautiful and foul-mouthed and she smokes filterless Mexican cigarettes. She was born missing her left arm below the elbow. On her right she wears charms and bracelets that jingle as she walks. She talks about indigenous feminism and the constricting Western interpretation of what feminism means. She describes how Rarámuri women’s status has been eroded, first by the patriarchy of the Catholic Church, later by the patriarchy of capitalism. Talking about injustice makes her curse more and speak faster, and I often lose thread—my Spanish is not strong enough. Which is a shame, because I want to hang on to every word she says.

“Eh, doesn’t matter,” she says. “English, Spanish. Languages of the fucking colonists.”

This is when I feel an urgency to hand over the soil from Geronimo’s grave. Digging it up at Fort Sill did not feel like a trespass. But here on the ranch I feel its weight. I want Kiriaki and her aunts to have it. Now.

I ask the women to huddle with me under a tree, a bit out of the rain. We stand in a circle and I palm the plastic bag over to Bernarda.

“Thank you for inviting me to your ceremony,” I say. “I brought this from the grave of Geronimo in Oklahoma. He is buried at a cemetery for prisoners of war on a US army base there. I want you to have it.”

Our circle falls inward. Like flower petals closing. For a few seconds we stand in a group embrace under the dripping tree, temple to temple in the flickering light of cellphones and bonfire. Then Kiriaki asks her aunt if she may hold the bag for a bit.

She places it on the stump of her left arm and cradles it there like a baby and caresses it through the plastic.

“I didn’t know he was buried in a military cemetery,” she says. “Motherfuckers.”

I apologize for the ziplock bag. “It’s the modern way,” I say.

She laughs.

“Postmodern,” she says.

5.

GUACHOCHI

For the opening speeches the next day we gather on a grassy island on a lake in the center of town where Guachochi’s few health-conscious locals walk laps at dawn. The real runners are in the sierra: the Rarámuri, whose name means “people who run on foot,” are the world’s most celebrated endurance runners. They routinely beat ultramarathoners from the United States. Four months before the ceremony, a twenty-two-year-old woman from Guachochi, racing in a traditional long-tiered skirt and huaraches made of tire rubber and leather strips, became the world’s fastest long-distance ultrarunner, beating 500 other women from twelve countries in the females’ fifty-kilometer category of the Ultra Trail Cerro Rojo.

The Rarámuri have been running in these mountains since the 16th century, when the Spanish chased them from the desert into small, remote subsistent farming communities amid a network of narrow footpaths that dip vertiginously into canyons and climb as vertiginously up. Running relays that last a day or longer is a ceremonial practice, a ritual celebration of events such as the harvest; running shorter distances, on the other hand, is a form of transportation, a fast way of getting from one place to the next. “When you run on the earth and with the earth, you can run forever,” goes a Rarámuri proverb. The reclusive Rarámuri became a global sensation after the book Born to Run: A Hidden Tribe, Superathletes, and the Greatest Race the World Has Never Seen, written by a US journalist, became an international bestseller. Around the same time, cartels began hiring Rarámuri as mules, to literally run drugs across the border.

Two dozen Rarámuri families come to the island to celebrate the commencement of the ceremony. For a while before a tasseled ensign embroidered with the words APACHES DESCENDIENTES DE GERÓNIMO—Geronimo’s Apache Descendants—everybody exchanges greetings: the animated Holguín clan; the suited officials from the Guachochi tourism department, which is sponsoring the event; the guests from abroad—a Lipan Apache activist and filmmaker from Austin, a Tewa Hopi medicine man from Arizona, a Danish-Norwegian documentary filmmaker duo; a husband-and-wife team of Lipan Apache lecturers from Lubbock, Texas, who travel around North America with two tepees in their truck. Three men in cowboy hats and boots and large buckles stand leaning back against a bench in that fashion men in cowboy hats and boots and large buckles like to lean back against things. Every new arrival shakes hands with everybody else, as is the custom; young girls reach up their cheeks to be kissed. A Rarámuri woman in a traditional flowered dress with a baby tied to her back asks me if she can take my photo with her smartphone. But I notice that after the greeting rounds the Rarámuri retreat to brightly colored clusters, keep to themselves. Is it the linguistic divide? Kiriaki rubs her right forefinger against her left forearm.

“Linguistic, no,” she says. “Racial, yes. It’s the skin tone. Like everywhere in the world.”

The Queen of all Canyons which cuts deep into the Sierra Madres once provided refuge for the Apaches who sought escape from the Spanish persecution. Photo by Jessica Lutz / IWMF Fellow for the Adelante Latin American Reporting Initiative.

The Queen of all Canyons which cuts deep into the Sierra Madres once provided refuge for the Apaches who sought escape from the Spanish persecution. Photo by Jessica Lutz / IWMF Fellow for the Adelante Latin American Reporting Initiative.

After two hours of speeches by the lake, the Holguíns and their out-of-town guests climb into minivans and trucks and caravan past eleven miles of apple orchards and cornfields to the Sinforosa Canyon. From the overlook at the rim the green vertebrae of the Sierra Madre crash down in grandiose near-vertical crags. Down down down, as deep as the Grand Canyon, past the caves where the Geronimo-Holguíns once lived, past Rarámuri running paths, past goat pastures, past marijuana plantations, down to the invisible Río Verde and her avocado groves—then up again, cresting in every direction. Dragonbreath clouds cling to distant mesas. Cenozoic lava droolings dribble down the sides of 250-million-year-old rock that buckled and folded and faulted to become what the locals call the Queen of All Canyons. Eras collapse here. Five centuries of European conquest are no more than a fleck. A redtail hawk hangs on an air thermal just below the rim.

“I remember visiting these caves,” says Hilda Holguín. “We still had relatives living there in the sixties. They didn’t feel like moving out. They were that poor.”

Or maybe they were still that afraid.

![]()

After the trip to the canyon Gina, Hilda, Roberto, Jessica, and I pile into a van once more. Clouds ball up in crevasses below Guachochi. Our driver, Bernarda’s youngest son Ángel, insists on showing us around town. From the back of the van Gina and Hilda narrate the landmarks:

“This is the first church of Guachochi.”

“This is the neighborhood where they say witches lived in the old days.”

“This is where, when they were laying sewage pipe, people found mammoth tusks.”

“This is the airfield, it was founded by three of our brothers.”

“They were the first pilots in Guachochi.”

“All three died in airplane crashes.”

Of course they were. Of course they did. We are in rarified air above clouds, with Geronimo’s descendants whose foremothers hid in caves and who go blind looking for truth. This is Gabriel García Márquez territory. Every eccentricity, every facet of beauty and tragedy is magnified here.

The airfield is empty: the town’s only biplane is elsewhere. Ángel ushers us out of the car and into the airport, through a kitchen where a man—an airport guard?—is heating up quesadillas, and into a patio. There is a wire mesh. On the other side of the mesh, under an awning behind some flowers, lies a Bengal tiger.

“She belongs to my friend, who owns the plane,” Ángel says. “Go ahead, you can take pictures.”

An artist friend whose work focuses on commodification of nature explained man’s ancient desire to own alpha predators: “What does it say about the power of possession; what status is created or projected through the ‘things’ we own?” To cage a tiger for amusement and display is to demonstrate domination. Just as it is to cage Geronimo and display him at an inaugural parade, for a good show. In real-life Macondo, metaphors are not always nuanced. They don’t have to be.

6.

THE FOREST

The Crown Dancers are five. They are big men, with much flesh. They wear black masks and tall headdresses made of wood slats and they run out of the forest naked except for buckskin loincloths adorned with bells. They ululate and growl and one of them is whirling a bullroarer. They gyrate and stomp and run at us and away. They are a terrifying masculine link between the natural and the supernatural worlds, and they lunge and stomp violently and ferociously to the accelerating drumbeat to summon mountain spirits that heal and protect. They bring awe and hope. On the overcast morning of the second day of the Ceremonia del Perdón, the day after the lakeside speeches and the airport tiger, they bring rain and lightning and thunder upon the forest clearing where we have gathered under ponderosa pines charred by electric storms past, and young madrones forever shedding some hurt, and massive rocks patinated with lichen, and at some imperceptible signal women one by one begin to orbit their centrifugal tempest. Roberto says to me, “Go, the women dance on the outside”—and suddenly most of us, women, men, children, in traditional dress and jeans and ponchos and rain slickers, in moccasin and rain boots and sandals and smart city shoes, wet and tripping over low brush, are dancing, dancing, dancing a wide sidestepping clockwise circle.

The Crown Dancers and their drummers came from the White Mountain Apache reservation in Arizona. Their journey took four days; their truck broke down in the mud at least twice. It is a small miracle that they didn’t get washed down some arroyo along the way to the waterlogged heart of Mexico. Then again, it is a miracle they could dance at all. In the early 1900s the United States outlawed ritualistic Indian dances. The Crown Dance, an important Apache healing ritual, was banned and had to be taught and practiced in secrecy until the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978. “Some say that ever since these ceremonial practices were outlawed they have never been quite the same,” writes the blogger Noah Nez, whose website, Native Skeptic, examines Native American spirituality.

As a link between natural and supernatural worlds, the Crown Dancers from the White Mountain Reservation in Arizona, are believed to summon the spirits. “Through their prayers,” explains Apache Medicine Man Manuel Cooley Sr., “the creator offers healing.” Photo by Jessica Lutz / IWMF Fellow for the Adelante Latin American Reporting Initiative.

As a link between natural and supernatural worlds, the Crown Dancers from the White Mountain Reservation in Arizona, are believed to summon the spirits. “Through their prayers,” explains Apache Medicine Man Manuel Cooley Sr., “the creator offers healing.” Photo by Jessica Lutz / IWMF Fellow for the Adelante Latin American Reporting Initiative.

The recently resurgent push for indigenous rights and sovereignty and clean water has unified around the revitalization of such rituals and ceremonies as much as around the issues of environment and sacred sites. But sometimes the rituals seem performative. At the inauguration of a small indigenous rights and environmental justice camp in Oklahoma last spring, one of the founders asked for a “prayer for collective consciousness.” Perhaps Nez is right; perhaps some authenticity was lost in this modern police-state isolation.

The Ceremonia del Perdón does not feel performative. It feels, as Kiriaki said, postmodern.

There are Rarámuri priests with shakers and a sacred malted drink in an earthenware jug. There is a tepee from Texas next to a Mexican flag. There is an amped mic, and two considerate portajohns, and speakers quoting the Colombian journalist Claudia Palacios (“To forgive is not to forget;” Bernarda) and the Chilean filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky (“The past is not fixed and unalterable. With faith and will we can change it, not erasing its darkness but adding lights to it to make it more and more beautiful, the way a diamond is cut;” Kiriaki). And there are us dancers: Bernarda and Hilda and Gina and Kiriaki. Roberto and Ángel and his sister Hillary, who is 16. The Tewa Hopi medicine man, and the Lipan Apache lecturers with the tepees, and Fox Redsky, an activist from Austin, a veteran of both the months-long standoff at Standing Rock and the Keystone XL pipeline protest, who is making a documentary about the Native tribes of Texas, none of which is officially recognized. A delicate feather tattoo swishes from the corner of her left eye.

Fox likes a hiphop song called All Nations Rise, by the Diné singer Lyla June. Toward the end June declaims: “They say that history is written by the victors. But how can there be a victor when the war isn’t over?” The post-conquest history of the Americas pustulates with so much unuttered and unutterable pain that we can only begin to contend with if we look it squarely in the face. Think of it as of recovering a genealogy on a continental scale.

This is not a history of explorers, seekers of religious freedom, and pioneer settlers spiked by the occasional thrill of a hostile encounter. (“Thanks to the Indians to provide a modicum of challenge and danger,” spits William S. Burroughs in his Thanksgiving Prayer.) It is, first and foremost, a history of a 500-years-long rebellion against oppressive regimes that stamp out this uprising over and over with varying degrees of brutality and self-congratulatory blindness.

“The post-conquest history of the Americas pustulates with so much unuttered and unutterable pain that we can only begin to contend with if we look it squarely in the face.”

In this history, who is Geronimo? The colonial mythology exoticizes him either as the last great indigenous freedom fighter or as the most violent holdout of Indian Wars; the US military picked the code name “Geronimo” for the operation to capture Osama bin Laden. But do you see a 28-year-old suddenly widowed, orphaned, and childless all at once? Do you see an Apache father in a country where the government pays bounties for scalps of Apache children?

“I have been more deeply wronged than others,” he would tell one of his biographers. I question the veracity of that statement. When Geronimo was a teenager, US forces rounded up nearly all the indigenous people east of the Mississippi, 70,000 in all, and marched them to Indian Territory along what is now known as the Trail of Tears. At least a fifth of them perished during that ethnic cleansing campaign. Within the next two decades, two-thirds of the indigenous population of Gold Rush California died of enslavement, starvation, reservation confinement, and targeted killing. Then came the genocidal massacres of the Indian Wars. From this historical standpoint, Geronimo’s life was as quotidian as his unremarkable death.

![]()

The Holguíns are lighting a ceremonial flame in a pedestal grill, to prevent a forest fire. One of Geronimo’s many great-great-grandsons, Alex Holguín, hands out pieces of paper. Bernarda has explained her idea for this: “It is a ceremony to ask God to forgive, in the name of our ancestors, the perpetrators and the victims. We will ask for forgiveness for the wars against Indians. For the turbulent times the consequences of which we are still suffering today.” People are already lining up to torch their pain. In the rain, smoke over the grill billows white.

I guess forgiveness means making peace. But I don’t want to make peace. Not with the prisoner of war cemetery at Fort Sill. Not with Charlottesville. Not with Tulsa or the Osage murders, not with the Holguíns’ abducted and enslaved grandmothers. Not with the orphaning of entire nations of their ancient rituals. Not with the banality of evil around the globe, nor with my own prejudiced cruelties and malice. All of them make me who I am, allow me to see the world the way I do, make me want to bring it to some kind of accountability. I must carry the heartbreak of it, this dark fire.

Hilda Holguín says it simpler:

“All these things I have, they form me,” she explains over a paper plate loaded with what she calls “Apache food:” a stew of potatoes, onions, hot dogs and ground meat cooked up in an enormous communal vat.

“I, too, didn’t have anything I wanted to forgive or reclaim in the fire. But my sisters really wanted me to write something and burn it. So I did. For my sisters. Because it is important to them, and they are important to me.”

I put my piece of paper in my slicker pocket.

I do not know what happened to the soil I brought from Fort Sill in a ziplock bag. I do not ask. “Historical events will not be dramatized for an ‘interesting’ read,” writes Layli Long Soldier in her poem 38, about the 38 Dakota men President Abraham Lincoln ordered to be hanged in the largest mass execution in US history, which took place the same week Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation. Back in Oklahoma the soil was a public part of the iniquitous drama machine that continues to titillate the Eurocentric American psyche, like Hollywood Westerns starring white actors in war paint, or the myth of the first Thanksgiving. But in Guachochi, among the Holguíns, the soil from Geronimo’s grave is not an historical event. It is a private matter and I want to respect its privacy.

![]()

I leave Guachochi the following dawn. I take a bus. It is a long day down the mountains; for the first three hours we weave above clouds. I take an aisle seat in the back. For a while a young Rarámuri woman sits in the window seat next to mine. She is wearing bright pink slacks, a purple faux leather bomber jacket, and dark blue earbuds connected to a pink Nokia phone, one of the earlier smart phone models that still has push buttons; she keeps it on top of a faux leather purse with busy floral design.

An hour or so outside Guachochi she squeezes past me with a smile and walks toward the bus door in the front. A few minutes later the bus stops to let her out on a curve. I take her seat; now I can look out the window. Slowly we pull forward and a minute or so later I see her in the piñon forest. She is sprinting down a path faster than any athlete I have ever seen, left hand holding her purse to her body, right hand slicing the air, a pink-and-purple spirit, running about her life the way people in these mountains have for centuries.

__________________________________

Anna Badkhen has spent much of her life in the Global South. Her work exposes the world’s iniquities by honoring the lives these iniquities most affect. Her immersive inquiry and has yielded six books of lyrical nonfiction, including Fisherman’s Blues: A West African Community at Sea, out in March 2018 from Riverhead Books. Badkhen has written about wars on three continents and is a 2017-18 writer in residency at the Tulsa Artist Fellowship, where she is at work on her first novel.

Anna Badkhen

Anna Badkhen is the author of seven books, most recently Bright Unbearable Reality, longlisted for the 2022 National Book Award. A Guggenheim fellow, Badkhen was born in the Soviet Union and is a US citizen.