For British Socialists, Fairy Tales Were the Best Way to Get the Message Out

Read "Nightmare Bridge" by Glanville Maidstone

British socialists in the period from 1880 to 1920 produced millions of words in print. A good deal of this is what we might call political rhetoric. One part, though, consisted of various kinds of nonrealist tales. The main body of these involved a recycling of the traditional literary forms like the fairy tale, the fable, the parable, the allegory, and the moral tale. Along with these, we find a few examples of the mystery tale. The home for most of this output was in the newspapers, magazines, and journals of socialist groups and parties. These mostly appeared as weeklies, which blossomed, were reinvented, or died out at quite a rate. The tradition of socialist journals is that the publication in question could represent a sectional interest, as with, say, the Miner, or a “tendency” within socialist thought, as with William Morris’s Commonweal.

This tradition of journalism was not simply a matter of an exchange of opinions, because the ideas were intertwined with crucial but much-disputed questions of action (When? How?) and organization (Group? Movement? Trade union? Party?). Behind every strike, demonstration, petition, or movement activity lay questions of whether the action would or would not achieve its objectives, or do anything greater than itself in terms of consciousness and political power. Then, as now, differences found shape within journals that could easily grow into antagonisms, rivalries, and splits, though the particular moment of these tales is marked by an extraordinary act of unity: the founding of the Labour Party in 1900, an organization that has overcome many divisions and splits and thrives today. The ideas fought over in this period live on both in the Labour Party and outside, and much of the landscape of present-day groups, ideas, and actions was laid out in that time. With specific reference to the tales here, any of us who listens to speeches or reads articles circulating today can call to mind socialists who’ve used some of these literary tropes and genres.

The leading figure in one of the socialist groupings in Britain, for example, used to regularly tell an old joke-fable about a rabbi and a goat, in which a poor man goes to the rabbi to tell him how terrible life is, what with the little home being so overcrowded. The rabbi tells the man to put his goat in the house. A few days later, the man goes back to the rabbi and tells him life is worse, the goat has made it even more overcrowded, and it’s eating all the food and leaving its droppings everywhere. The rabbi tells the man to sell the goat. A few days later, the man returns and thanks the rabbi profusely: life is so much better, there’s more room, and everyone’s happy! It’s a little morality tale about how easy it is for people (politicians?) to look as if they are changing something when in fact it stays the same. Other left-wing speakers have, for example, cited “two bald men fighting over a comb” (pointless war) or “one of two cheeks on the same arse” (seemingly different views that are in reality the same). My great-grandfather, born around 1860, used to explain to my father what a trade union is: “Like a box of matches. One match, you can break. Two matches you can break. Three matches also. But a whole box, you can’t break. That’s a union.”

![]()

The following story, “Nightmare Bridge,” was written by Glanville Maidstone and published in 1910.

I knew in my dream that I was lost. Weary and cold, with aching feet and heavy eyes, I plodded along that silent and solitary thoroughfare of a great city. The vista seemed endless; the winking lamps stretched on as far as one could see. Far as I walked I had met no one, not even a policeman. Stay! There is a constable standing in the shadow of a gateway. I stop before him; I ask him whither does this road lead. He looks at me with strange eyes; he does not speak, he whispers: “To the bridge.” He is very pale, the constable, and very lean. His face—his face is like a skull: it is a skull. No; but how hollow are his eyes! How sharp and prominent are his cheekbones! And as I turn away he laughs. His laugh puts fear into my heart. I turn cold with fear. I try to walk rapidly away from him, but my feet are like lead. And he follows me. I hear the sound of his feet, and the echo of his measured step comes back from the dark and silent houses. Will this road never end? Do those glimmering lamp-lights stretch on, an avenue of stars, to the edge of the world? Where is this bridge? Why did he call it the Bridge? I tramp on, the constable following without a word. Then—then I see the Bridge. I am on the Bridge. It is a wide bridge, brilliantly lighted, exquisitely paved. There is a broad footpath on either side, and lines of gilded railings. Overhead stretch festoons of beautiful flowers. The road is used by motor cars and handsome equipages drawn by noble horses. In the carriages and cars are men and women dressed luxuriantly. I can see the sparkle of gems and hear the sound of conversation—conversation gay and witty, carried on in high-pitched aristocratic voices. The traffic in the roadway is not dense: there is ample room. On the footpaths there are but few people; they are the counterparts of those in the carriages: men and women, handsomely dressed lounging easily, laughing and talking: a picture of wealth and happiness. Outside the railings?—outside the railings it is dark. There seems to be partly visible through the shadowy obscurity a moving crowd, a dense traffic. There is a great deal of noise: the noise of tramping horses, heavy wheels, cracking whips; the noise of angry voices, or curses, sobs, and groans. What goes on there in the semi-darkness? Is it a riot? Is it a battle? Hark! a scream!

What bridge is this, then? What does it span: a river? I look for the terrible constable. He is at my side. He shrugs his shoulders and says, in his horrid whisper: “You do well to choose the middle of the Bridge. You would not enjoy the outer roads. I know: I used to be among it.”

“What does it mean?” I asked. “What is it? Let us go there, where the noise is. Let us go and see. Come, come, come; let us go to the side of the road, where the crowd is.”

“Come,” said the constable, “I don’t care. I’m safe enough—unless I lose my feet or my head.”

“Lose your feet? What do you mean?” I asked.

“Come and see,” says the constable, with a grim smile. “If a man goes down in that crush he gets no quarter: not from them.”

“From whom?”

“From his fellow creatures.” The constable leads me back towards the entrance to the bridge. “If you fall,” he says, “do you know what they will do to you?”

“Tell me,” I ask him.

“Well,” he says, “you be careful. If you fall they will kick you; they will trample on you; they will hustle you over the edge, into the river.”

We are on the Bridge—on the outer road. What dense traffic! what a terrible crowd! There is not room. There are no footways, and the heavy traffic is mixed with the struggling pedestrians. On the outer side, next the river, there is no parapet. The people fight frantically to keep away from that edge. But they cannot. Hark! another scream! “What is that?”

“Another one gone over,” says the constable, “a woman. She’s too old and weak to fight. Many of the weak ones go: men and women, and children, too—very many children.”

In appearance this crowd resembles an ordinary London crowd—of poor people. The crush is so severe that at every few yards distance we see groups fighting—fighting like animals—fighting as I have seen women and men fighting round the tram cars and the motor omnibuses. And the constable spoke the truth. When a pedestrian—man or woman, yes, or child—goes down, the case is desperate. A girl falls close by us. Another woman kicks her, a man treads upon her; when she screams a second woman strikes her in the face. Then—oh, a huge wagon laden with iron crashes through the crowd. A man is down—down under the wheels!

“In the name of Heaven,” I cry, turning to my sardonic guide, “what does this mean? Why do they not widen the Bridge? Why do they not put a parapet on the outer side?”

“No money,” says the constable. “Who’s to do it?”

“Do it!” I exclaim. “What kind of city is this? Is there no government—no authority?”

“Of course,” the constable answers. “This is a civilized country: a Christian country. Government? What are you thinking about?”

“Then,” I say, “tell me, who governs this city? Who is responsible for this bridge?”

The constable nods his head towards the wide and beautiful central roadway. “Those,” he answers; “those ladies and gentlemen, there.”

“But,” I cry, “those people take no heed. They are lounging, talking, trifling, laughing. Do they know that men and women are being crushed to death? Do they know that little children are being hurled into the river or crushed under foot? Why do they not stop these horrors? Why do they not widen the bridge?”

The constable shook his head. “I told you,” he said, “you would be better in the middle—seeing you’d had the luck to get there. They cannot widen the bridge, do you understand, outwards; they could only relieve the crush by throwing down the railings and throwing open the wide middle road. That’s the difficulty.”

“But,” I said, “in the presence of this awful crush and struggle, this terrible suffering and loss of life, surely they could do as you say! There is room on the bridge for all and to spare.”

“True,” the constable nodded. “But,” he said, “the middle way is theirs, do you see? Naturally they will not give up any of their room; that is why they have put up those gilded railings. There are very few can climb those railings.”

“But the crowd,” I said, “will the crowd endure this? They are so many. They could pull the railings down.”

“They are very strong,” said the constable.

“If they are made of steel—” I began.

“Steel?” The constable laughed his horrible laugh. “They are made of something stronger than steel,” he said.

“Of what are they made?” I asked.

“Of lies,” said the constable, and kicked a fallen man out of his way.

“But,” I cried, “Lies can be broken with truth. I will speak to the people. I will appeal to them for the sake of their women and children. I will give them the truth to break these lies.”

The constable shook his head. “Do nothing of the kind,” said he. “Go back to the middle way. You will hardly be heard in all this noise; and how can men listen or understand when they are fighting for dear life? They will pay no attention to you; or they may throw you down, and then they will trample on you. Go back to the middle way.”

“Then,” I said, “I will appeal to the ladies and gentlemen of the middle way. I will tell them what I have seen.”

“No use,” said the constable, “those people on the middle way like a lot of air and space; they like to be grand, and they like to be happy. They keep their eyes away from the side road, and talk beautifully about all kinds of noble ideas and pleasant things. But they’ll see you damned before they will give up an inch of their room. Try them. Nice, polite, refined, well-spoken ladies and gentlemen they are; but try to take a foot of their road, and you’ll think you have been thrown to the lions.”

“But,” I said, “it is horrible. It is infamous. These people are worse than savages. This city is a disgrace to humanity.”

“Steady, steady,” said the constable. “What city do you come from?”

“I? I come from London.”

The constable laid a bony hand on my shoulder. His pale face grew redder, his smile became more human, his baleful eyes twinkled humorously, and his whisper rose to a firm, deep voice. “Why,” he said, “London? Bless our two souls! London! Don’t I know London? Don’t I know that London is just exactly like this? Why, governor, this is London. What part is it you want to go to? Now then, wake up, mister; you must not sleep here.”

“Good heavens! Why—fancy my falling asleep in a railway station! In the refreshment bar—”

“Well,” said the constable, “the bars are closed, sure enough. Not,” he added, “but what there might be ways of getting something if you really feel the want of it, sir.”

And there were.

__________________________________

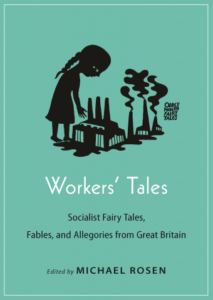

Excerpted from Workers’ Tales: Socialist Fairy Tales, Fables, and Allegories from Great Britain ed. by Michael Rosen. Copyright © 2018 by Michael Rosen. Reprinted by permission of Princeton University Press.