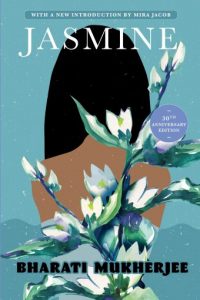

Finding Nuance and Much-Needed Relief in the Writing of Bharati Mukherjee

Mira Jacob on Reading Jasmine

When I was growing up, the idea that I might need to see myself in the stories I read was framed as unsophisticated at best, narcissistic at worst. Yet, in America in the late 1980s, a good portion of the country was doing the exact same thing without ever acknowledging it. The frictionless-ness of whiteness—which is to say, the way white Americans could move through the world finding their every nuance reflected in music, literature, film, the fine arts, and media—ensured their belief that their experience was the one-size-fits-all of perspectives. I even believed it myself, or tried to, squashing my unease to better align myself with Mark Twain’s Huck Finn instead of slave Jim, with Jack Kerouac’s Sal Paradise instead of “the cutest little Mexican girl” he loves and leaves in On the Road.

I learned very early on to ignore the fact that certain characters never felt quite as real as others, that certain people with certain identities were cast in the peripheral roles of the story. Their interiors were dry and obvious, their needs basic, if they had needs at all. A dark young woman from India, for example, could only really ever exist in her usefulness to others—a daughter, a nanny, a wife—and her place in the story was nearly always the sidebar on the way to a larger narrative. Even her internal life—what she wanted for herself—could not breach these borders, when she was imagined by white bodies, by male bodies.

Reading yourself as a simple character over and over gives you two choices, both equally sad: One is to buy into your own lack of complexity. The other is to align yourself with whiteness so you can think of yourself as complex. Both of these are murder on a young brown woman’s mind, which is why finding Jasmine, in all her contradictions, felt like living for the first time.

Unsurprisingly, perhaps, Jasmine’s complexity is not what was highlighted on the original flap copy, which described her as a woman who “seems fated to a life of quiet isolation in the small Indian village” but then comes to America only to be “greeted by a brutality as primitive as any she has known”; one who meets “a self-assured young couple in Manhattan” and is confronted by “the mysterious emotions of Occidental love.” Of course, I knew what this meant. I had seen it so many times before, the coded language that lets readers know they are about to witness the transformation of a poor, unlucky immigrant into a good American, to be shown “the shifting contours of an America being transformed by her and others like her—our new friends, neighbors, and lovers.” Obviously, the writers of that copy had never once considered an Indian American reader, much less the fact that I could not simultaneously be myself as well as my own new neighbor. But did it matter? Not really, I told myself. Not in a way I could explain to myself or anyone else. So I settled behind the gaze the publishers assumed I had, watching myself like they watched me.

How strange it was to hold Jasmine at that cool distance, to set myself up for a story I had seen a thousand times before, then to crack it open and find my own face staring back at me. Sure, it was the story of Jyoti/Jasmine/Jane, a woman who shed names and identities to simply keep surviving every day in America. And yes, she was an undocumented immigrant while I had been born in the US, Hindu where I was Christian, 22 and pregnant to my 16 and inexperienced. But that didn’t matter nearly as much as what I saw in front of me: a brown body stranded in the middle of the country, a dark spot on acres and acres of whiteness. A woman required to explain to neighbors, bank tellers, teachers, grocers, even children, where she was from, to endure their free associations about that place, to cook its food so that they might pride themselves on eating it. To keep telling herself that they were good despite all of this. To admit, in a single sentence that took my breath away the first time I read it: “This country has so many ways of humiliating, of disappointing.”

She was funny, this Jasmine, and ruthless in ways both obvious and deft.

But where was the grateful immigrant the text promised? Where were the teachable moments provided by kind and benevolent Americans, and her admiration of those who had instructed her? They were not here. Instead there was Jasmine, observing in bold, indicting strokes why her lover changed her name from Jasmine to Jane: “My genuine foreignness frightens him. I don’t hold that against him. It frightens me, too.” Nor was the simple immigrant naïveté from the flap copy present in the darkly observant mind that tallies up the small hypocrisies all around her and quips about a Great Depression survivor that “in the beginning, I thought we could trade some world-class poverty stories, but mine make her uncomfortable.”

She was funny, this Jasmine, and ruthless in ways both obvious and deft. She knew how to use a knife to defend herself and how to use her exoticism as its own weapon, the unknowability it offered her as protection against minds that would prefer to sum up and dismiss her. She saw, as I did, what it would take to survive in America, and went about the daily business of doing it. She wanted, as I did, to be loved and seen by her country, but settled instead for its wavering tolerance.

Where just moments before I was sure that this was my book, that it was my story, I now felt myself bumped from it again, in a direction I hadn’t known existed.

What was it like, at age 16, to read something that finally addressed the truth of my life? To watch the always-supporting cast member step center stage, and tell her story? To see, in Jyoti/Jasmine/Jane’s constantly shifting names, all the portions of myself I’d had to leave behind entering “American” households, institutions, workplaces? To feel her intelligent and precise fury, the way she kept it at bay by reminding herself that those causing her pain were not trying to do so, to feel how so much of that daily practice hinged on her having no other viable options? It was like putting on a shirt and seeing, for the first time, the shape of my own invisible body.

And then, almost as quickly as it came, my moment of recognition dissolved into this passage:

There are national airlines flying the world that do not appear in any directory. There are charters who’ve lost their way and now just fly, improvising crews and destinations. They serve no food, no beverages. Their crews often look abused. There is a shadow world of aircraft permanently aloft that share air lanes and radio frequencies with Pan Am and British Air and Air-India, portaging people who coexist with tourists and businessmen. But we are the refugees and mercenaries and guest workers; you see us sleeping in airport lounges; you watch us unwrapping the last of our native foods, unrolling our prayer rugs, reading our holy books, taking out for the hundredth time an aerogram promising a job or space to sleep, a newspaper in our language, a photo of happier times, a passport, a visa, a laissez-passer. We are the outcasts and deportees, strange pilgrims visiting outlandish shrines, landing at the end of tarmacs, ferried in old army trucks where we are roughly handled and taken to roped-off corners of waiting rooms where surly, barely wakened customs guards await their bribe. We are dressed in shreds of national costumes, out of season, the wilted plumage of intercontinental vagabondage. We ask only one thing: to be allowed to land, to pass through, to continue.

Reading these two paragraphs loosed a strange, troubling dissonance in me. Where just moments before I was sure that this was my book, that it was my story, I now felt myself bumped from it again, in a direction I hadn’t known existed. Was it really possible that this hidden world of human freightage existed in parallel to the public one I had grown accustomed to navigating? That shadow airlines filled the sky with people who were so intent on getting to a place that they let go of the idea of ever going home? That I had, by nature of my nationality, and class, and passport, managed to live almost until adulthood without even once glancing in the direction that they had emerged from?

Decades later, we would have words for this, the privilege of my ignorance, the entitlement of my citizenship, but right then, in that moment, I could only register it as fear. Fear of the magnitude of a struggle I had never even had to contemplate, and, if I’m honest, fear of the desperation that drives a person to take that kind of voyage, to risk their own life for the promise of a better one. What was it like, at age 16, to understand that as much as I had not been seen by my country, I had also been blinded by my own American-ness? To begin to realize that to live in my body would be a constant unraveling of my own hypocrisies? To recognize that my oppression and freedom worked in lockstep, two sides of a coin that would always be twirling midair? I probably would not have said it then, staying up so many nights in a row trying to accommodate the new realm of feeling Jasmine gave me, but now, at a time when our country has built concentration camps at the southern border, when our president encourages white Americans to view the rest of us as undeserving outsiders, I can tell you it was a gift, the kind that very good literature offers us. It is the gift of being allowed to see ourselves in all our inconsistencies, to reckon with what it means to be an insider and outsider at the same moment. To understand our oppressions and exertions of power. To build our hearts so they might always reflect, like Jasmine, what it means to carry what is fraught and scared and dismissive and hopeful and wild inside us, and choose love.

__________________________________

From Jasmine by Bharati Mukherjee, with a new introduction by Mira Jacob. Used with the permission of Grove Press.

Mira Jacob

Mira Jacob is the author of the critically acclaimed novel, The Sleepwalker’s Guide to Dancing, which was a Barnes & Noble Discover New Writers pick, longlisted for the Brooklyn Literary Eagles Prize, and was named one of the best books of 2014 by Kirkus Reviews, the Boston Globe, Goodreads, Bustle, and The Millions. She is currently drawing and writing her graphic memoir, Good Talk: Conversations I’m Still Confused About (Random House, 2019).