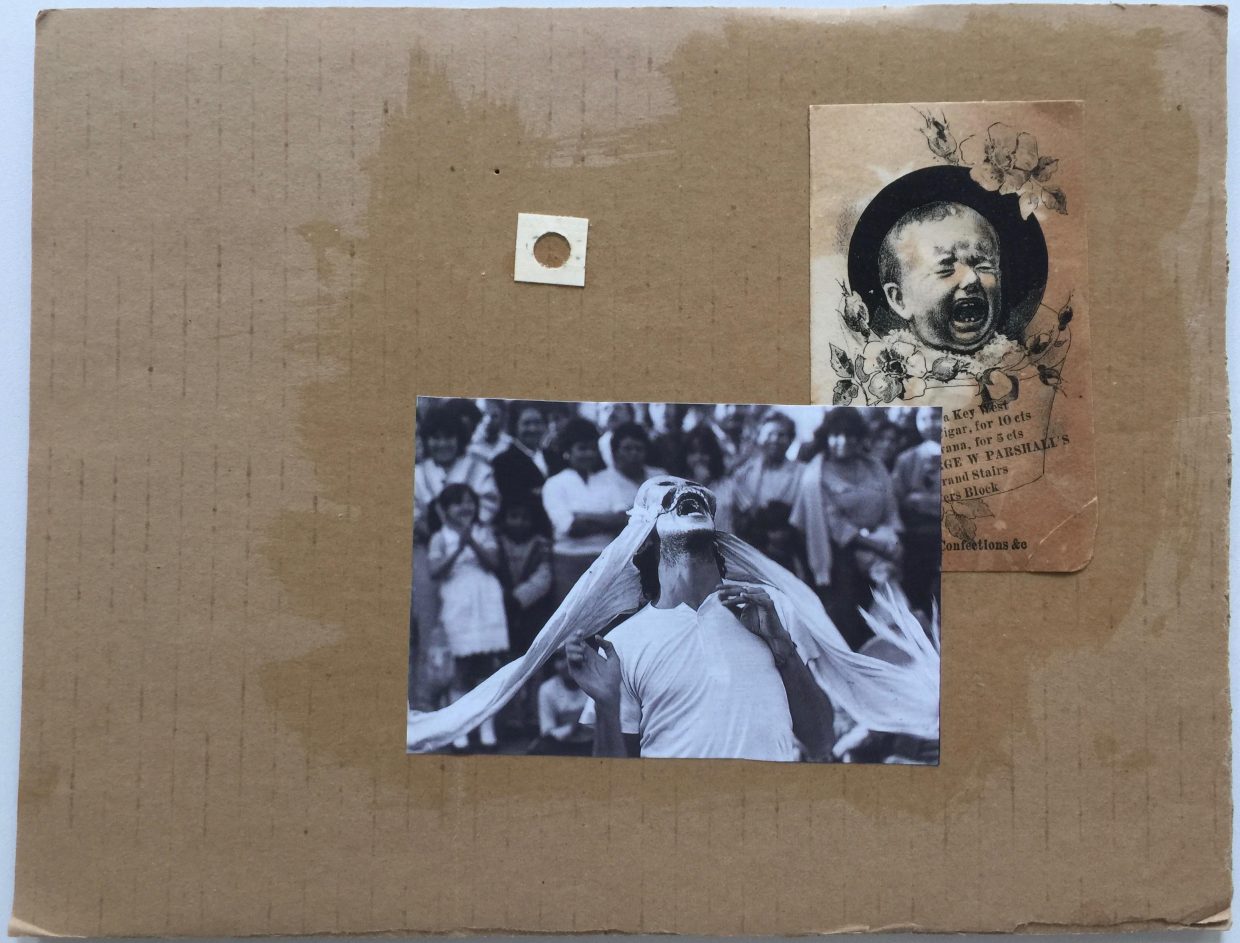

For a few (many) years I was looking for a place to be—unsettled, wandering years. Whenever I’d find myself in a new city, I’d give myself a task: to gather three pieces of ephemera, which I could then use, at some later point in the day, to make a collage. This ephemera was usually paper. This was often simply for ease of transport. I was traveling, I couldn’t load my bag with, say, bits of rusting metal (something that always still grab my attention, and that I will still gather, when I’m closer to home).

As I went along, I developed criteria for the ephemera:

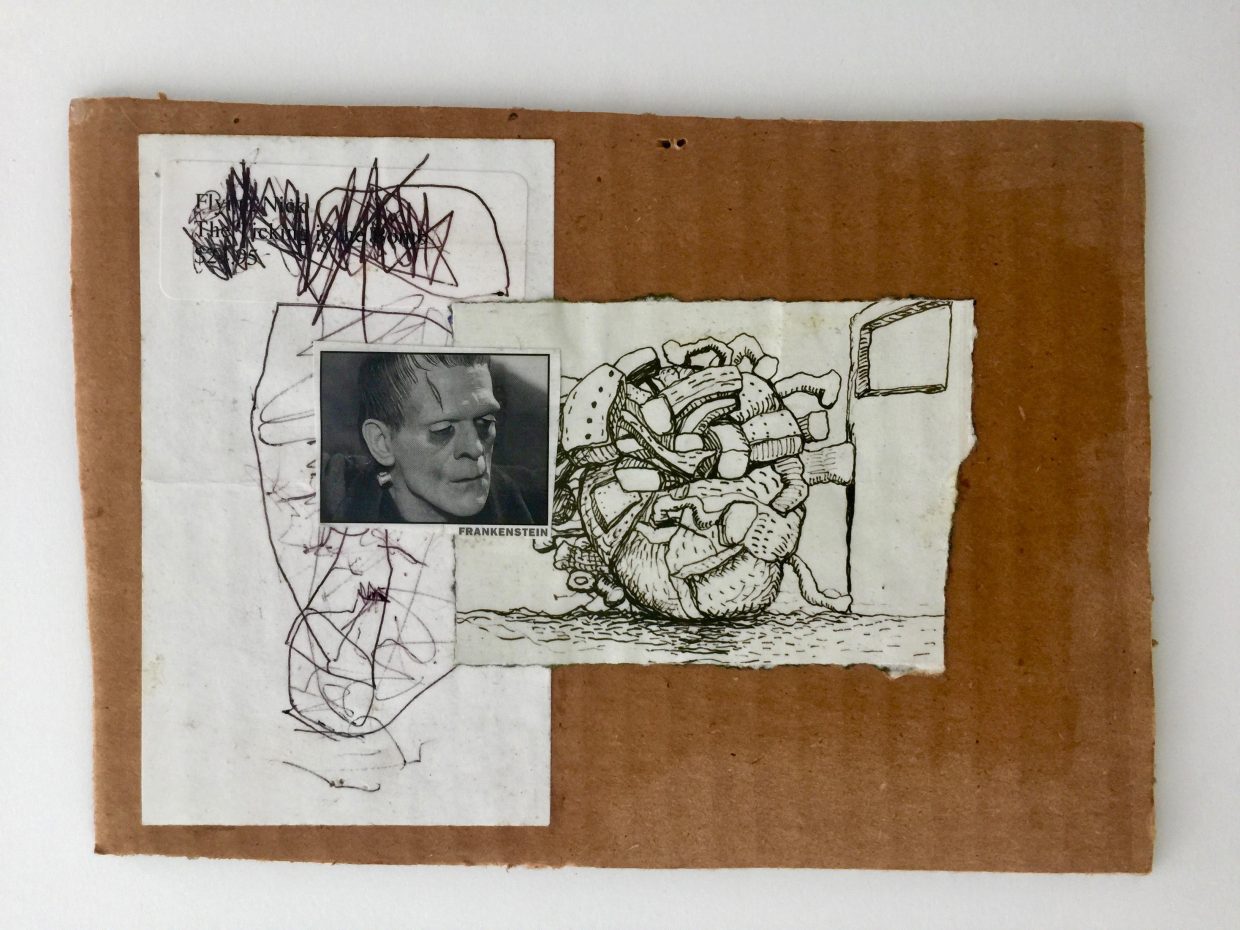

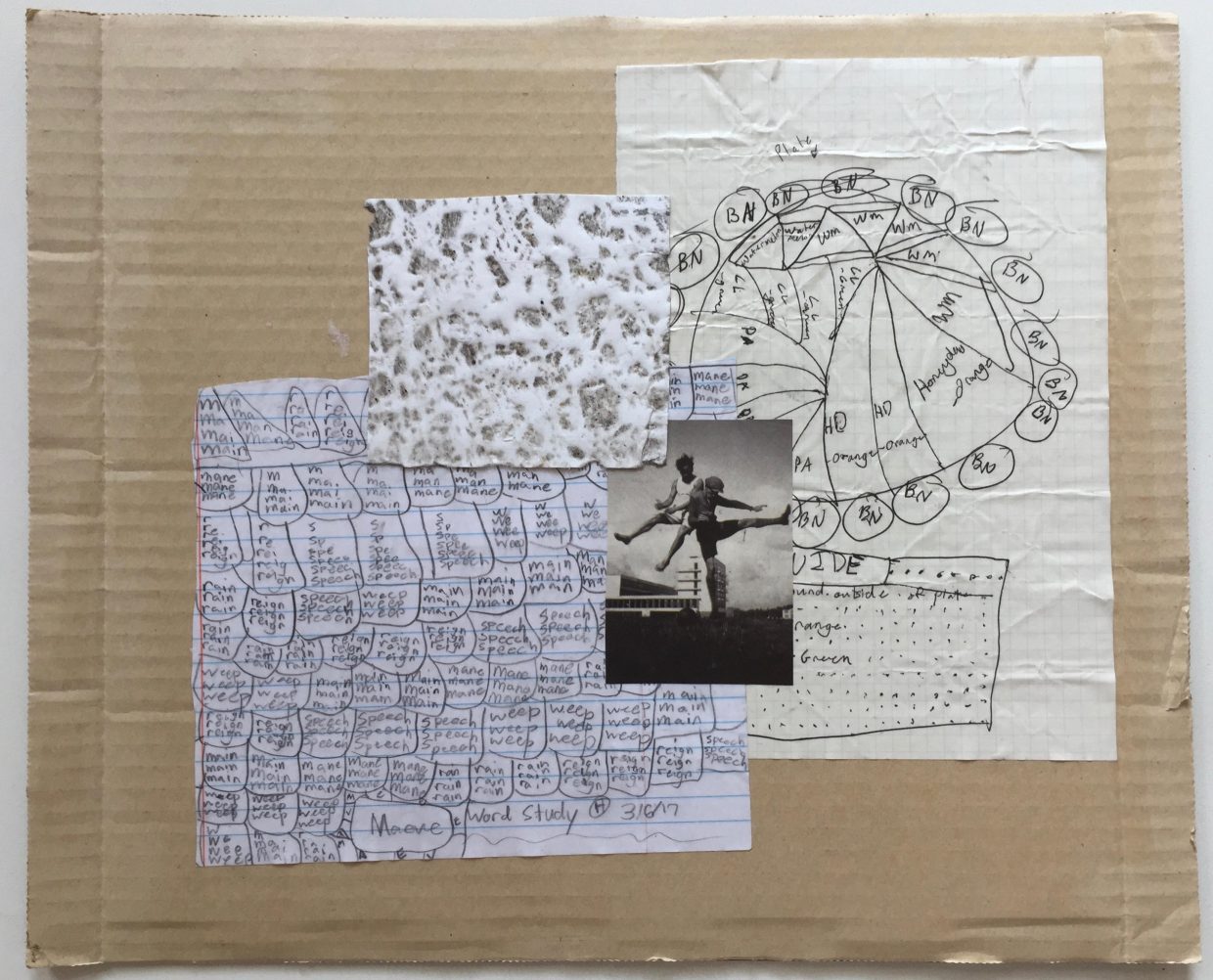

–It had to be paper (or at least paper-thin), preferably a scrap someone had scribbled something on, or made a small sketch on—maybe a child’s drawing, maybe a carpenter trying to clarify a tricky joining, maybe a shopping list.

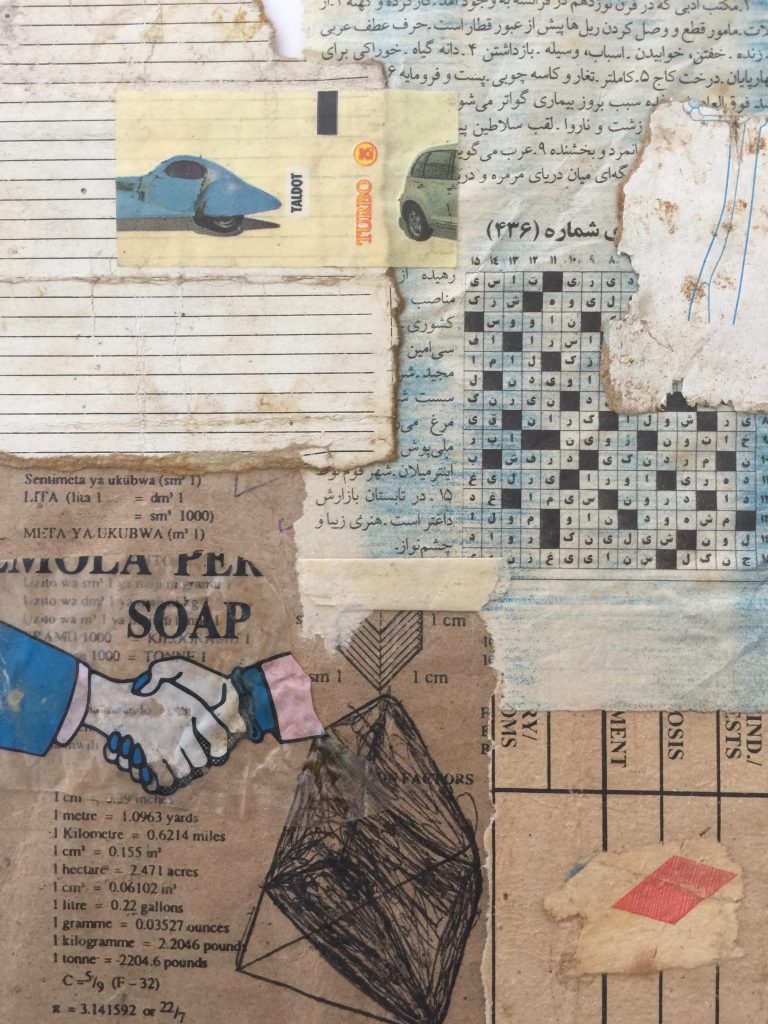

–Preferably, it would be weathered, left outside, stepped on, so that it contained a palimpsest of the sidewalk (think of a gravestone rubbing).

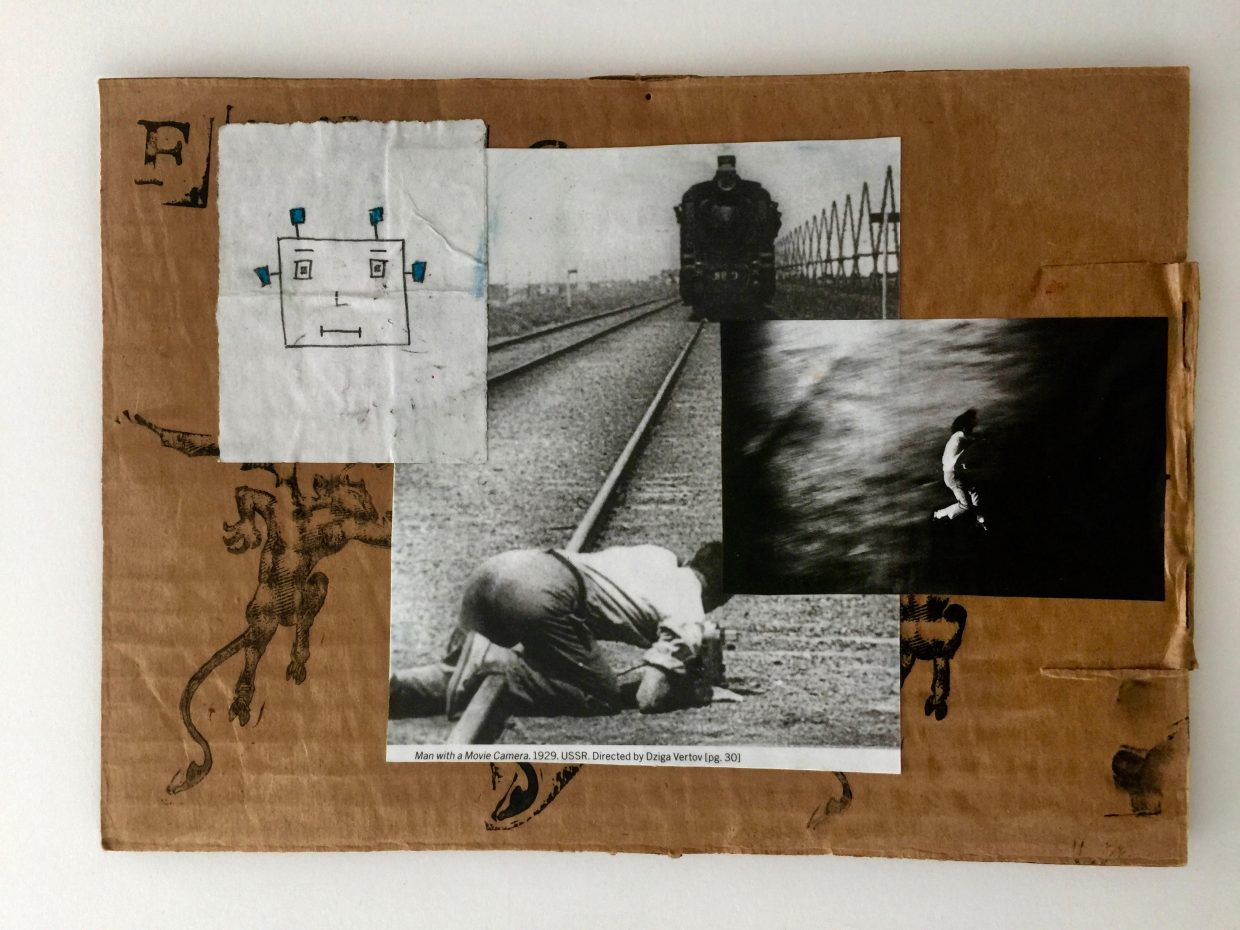

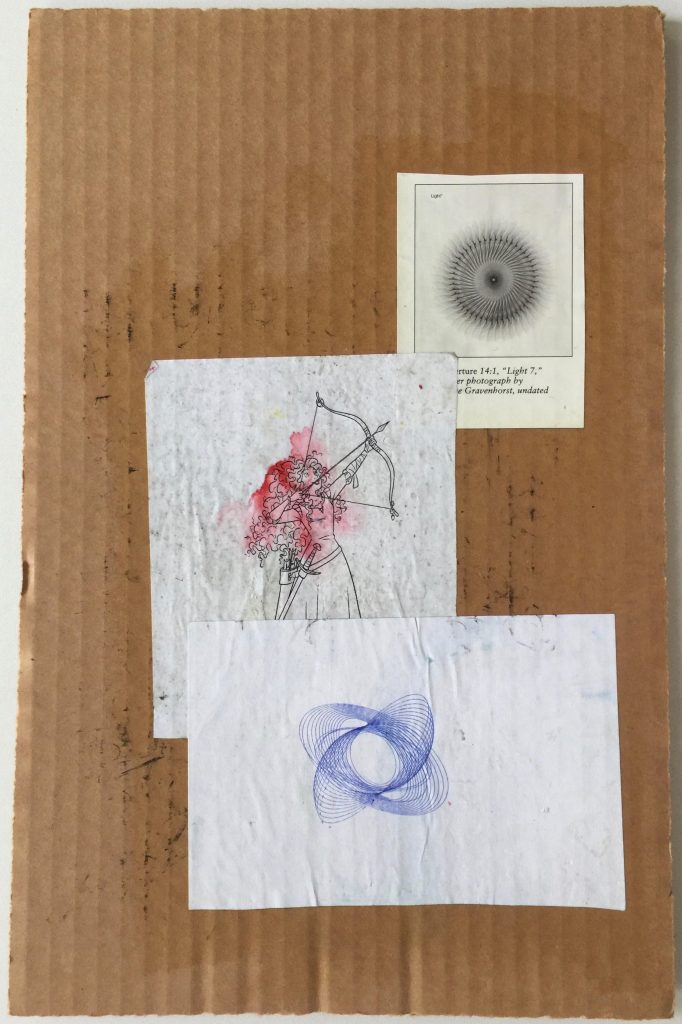

–The listings for a museum or a movie or an art opening were a good place to find a thumbnail image of what was showing that day.

–Something that had a word or two of the local language on it.

–Color was often a way to united these three seemingly disparate elements, beyond the fact that I’d already united them, simply by bending down and putting them in my pocket.

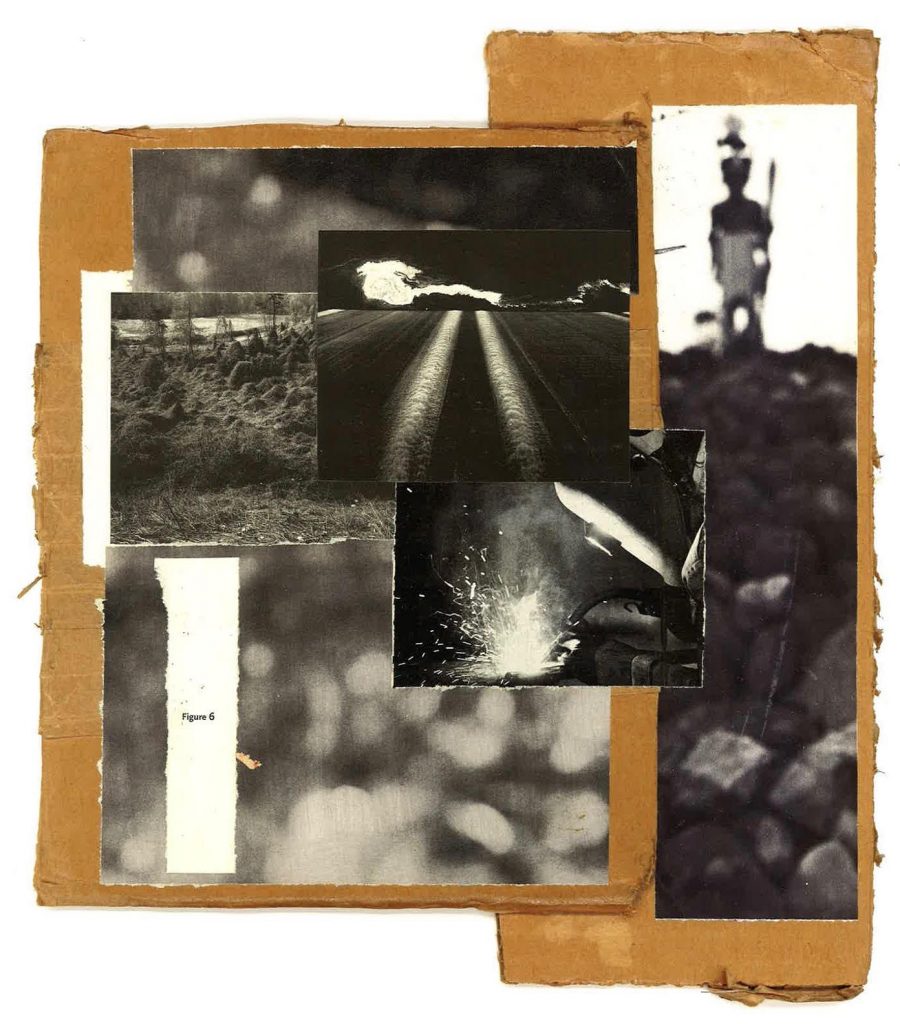

I’d also need to find a stationery store, to buy a notebook and a glue stick. This was normally accomplished just by wandering, maybe by asking someone on the street. The stationery in Eastern block countries felt frozen in time, unchanged from when the Wall went up. In Tanzania the paper seemed to have been recycled many times. In Vietnam there was a care and range of options that was thrilling. Back in my hostel or in a café I would then arrange what I’d gathered into a collage.

Sometimes, instead of a notebook, I’d make this collage on a separate piece of paper, or on a piece of cardboard (weathered) I had found. In this way each would become a map, of sorts, of the new city, and when viewed sequentially, an atlas of my journey. It gave me a clearer sense of where I had been than any photographs I took. It triggered my memory in a different way.

*

I rarely showed these collages to those I met along the way. They were private, intimate, even a little embarrassing. For the most part I kept them hidden. I wasn’t making them for anyone else. I couldn’t say why I was making them.

Some (most) would call it trash.

In this it reminds me of the book Sacred Trash, which begins with a discussion of the Hebrew term “geniza,” which can be loosely translated as hidden or stored up. In what we now call the ancient world, any piece of paper (or parchment or vellum) with a word written on it could not be simply discarded, as it could be the word of God. It had to be stored away, sometimes hidden, allowed to “decay of their own accord.” In the Middle East caches of this “sacred trash” are still being discovered, each of which gives us a glimpse into this lost world.

*

For the past dozen years I have lived a few doors down from an elementary school, the same school my daughter attended until she moved on to middle school. The sidewalks and playgrounds around schools are goldmines, for the young shed their gold continuously. A pencil drawing of a car by a child is gold. For a couple months I made collages on an island just south of Zanzibar, where the children had never actually seen a real car, only in films or on the tattoos they would find in bubblegum packs. These children’s drawings of cars are especially precious.

*

I once made a rule that once I’d gathered those three bits of ephemera I’d stop looking. The problem was I never stopped looking. Then I made the rule that if I found a fourth item then I’d have to discard one of the previous bits. This turned out to be unworkable, for my temperament. I had already become attached to the first three, I had already seen a pattern emerging, a weave. The fourth might add to that weave or suggest an entirely new one. No one was watching, no one cared. I found that I would simply hoard all four.

To hoard is another way to translate “geniza.”

*

Bill Traylor has always been one of my favorite artists. He is classified as “outsider,” though I have seen his work in several museums. For his ink silhouettes, Traylor would only use cardboard that had been outside for a period of time. Weathered. A patron once brought Traylor some stretched canvases, but Traylor abandoned them. The blank canvases didn’t speak to him. They didn’t suggest a story. They didn’t already contain some piece of the story that surrounded him each day. In this way his drawings are more of a collaboration with time, with weather, with his neighbors and everyone who passed by his sidewalk perch.

The story of Traylor being offered clean canvases reminds me of a story I’ve heard about Francis Bacon (who is now the opposite of an “outsider”). You’ve no doubt seen the stunning chaos of his studio (look it up if you haven’t). Bacon collaborated with everything around him—from monographs of Muybridge to passages from The Wasteland—whatever snagged that moment on his subconscious. At one point, once fame had found him, he moved to a new—tidy—studio. Yet, like Traylor, Bacon couldn’t paint once the chaos of his studio was gone. He returned to his chaos.

*

Now, in my studio, I keep folders and piles and boxes of what I’ve gathered. Not all of it is gathered from the sidewalk. Some of it is from fliers from art house movies theaters (metrograph, film forum). Some are drawings my daughter makes, which she leaves for me to use as I will. For a few years when she was younger we would spend a few hours a week making collages collaboratively. Now she leaves me things she finds in her walks through the city. If we are together we will judge this scrap or that, and one of us will bend and marvel at the image or texture, and slip it into our bag. We don’t always agree. Her eyes is different from mine, which is as it should be.

*

I have chosen to show these now, in my new book Stay. The act was initially private, then it expanded to include my daughter, then I began giving them away to friends. But this is a way to fold them back into the universe.

__________________________________

Nick Flynn’s book Stay is available from ZE Books.