Finding Creativity in the Wintertime Rhythms of a Bordeaux Vineyard

Mari Andrew on a Restorative Trip to France

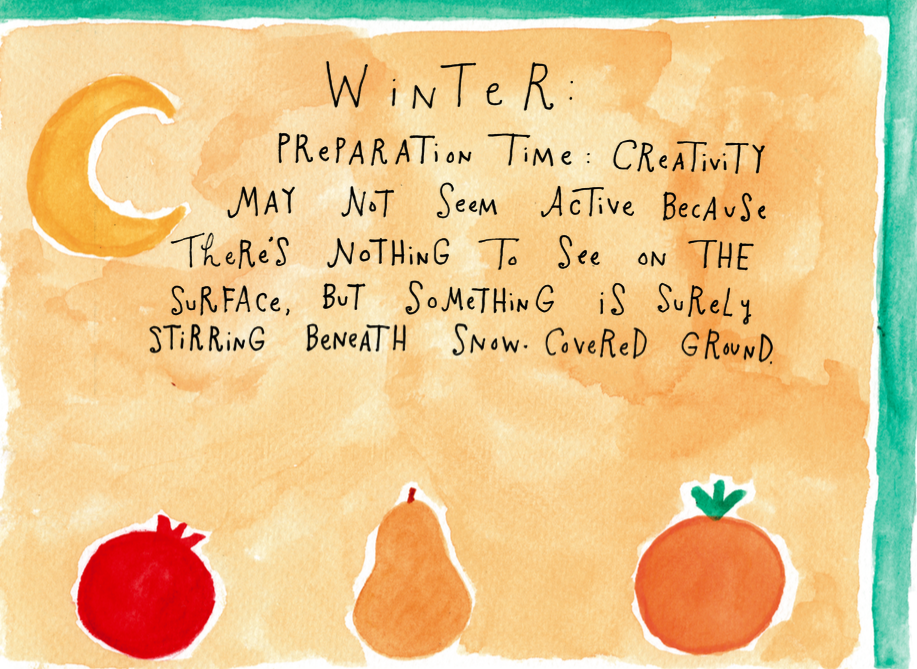

When I worked full time in non-creative jobs and only communed with Creativity after-hours, at bars and in the comfort of my dimly lit desk, I didn’t realize how erratically behaved she was. After I finished my second year as a full-time artist, however, I was familiar with this side of her, could easily chart our ebbs, flows, delays, and dry spells. By the time I began my third year as a full-time artist, I had a hefty collection of Creativity-dependent unknowns: where jobs would come from, how I’d make money, and how and when she’d choose to show up.

Creativity was like a flaky friend who never remembers to RSVP but then appears at the party in a Gatsby-level gown and with a gift of expensive champagne. She didn’t seem to have a favorite day of the week or type of weather she thrived in. I imagined her swirling a dry martini and laughing at my naive hubris when I thought I could control her.

My work now depended on this invisible force who kept strange hours and threw tantrums without warning. I’d endure weeks at a time where she’d fail to visit me and I’d start doubting my judgment, and then she’d throw open the doors and come through with a dramatic “Miss me?”

She was intoxicating to be around, perhaps because of the very real possibility that she might leave for good at any moment. I worried Creativity would become easily bored with me and go on to the next thing, with no concern for my paychecks and my dreams.

That winter, to escape February in New York—a pretty bleak month where we’re getting sick of the snow but know there will be at least a few weeks more of it—I booked an astoundingly cheap flight to what turned out to be the astoundingly empty south of France. I guess people who want to get away from a cold climate are more inclined to devote their resources to a significantly less cold climate rather than to a very slightly less cold one.

I used to get my best ideas in the midst of new scenery—Creativity seemed to enjoy accompanying me on vacation—but, for the first time in three years, I wanted to relieve myself of that pressure on this trip. It felt risky to do so, like if I didn’t keep writing and making art, I’d forget how. But if this was going to be my career, I needed to learn how to take a few days off from worrying about Creativity, and instead learn to trust that, even in her capricious moodiness, she would come back to me again.

When I arrived, Bordeaux smelled like sweet rain. It didn’t rain the entire time I was there, but somehow it was always wet. The sidewalk tile was slippery under my feet, and I had to walk cautiously, like one of the plump ducks that waddled along the river. Of course, the Bordelais people, in characteristic French effortlessness, could gracefully clip along the slick stone streets in heels.

It all seemed so magically and terrifyingly precarious. An early frost or one little bug could destroy a year’s harvest.

Because I love to dress up for travel, I brought with me the frilly long dresses and ruffly tops and satin hair ribbons I couldn’t quite find the occasion for in New York. I told my friends I felt like Belle in her Christmas cloak. My clothes matched the scenery perfectly: lots of ivy curling up the sides of produce shops and spectacular plazas that could make anyone feel like they were about to attend the opera.

A river splits the ancient city in half. During the days, I wandered back and forth between the two halves, fueling myself with inelegant seafood lunches at loud, communal, family-run bistros with checked tablecloths. These uncouth, laughter-filled bistros were a very different picture than the typical prim Parisian cafe, but they were more my speed. I sat in damp, sumptuous bars, drinking red wine at 4 pm, when the sky began to crinkle inward and the limestone buildings began to glow violet, with not much to do except look around—and it was a very nice city to look at.

One afternoon, it was actually warmish enough to sit outside. It seemed I had the same idea as most people in the city. (I spent a lot of time wondering if people in France had jobs.) I took over a bench and decided to face the people rather than the water. With my mittens on, I sipped a coffee from a nearby kiosk, watching the world around me.

I watched the sun struggle to peek out beneath a dominating cloud. I studied a boat that seemed to be making its way across the river unusually slowly, when its captain emerged from behind the helm, smoking a cigarette.

I observed a man feed his poodle scraps of his pastry, but only if the dog first stood on his hind legs and clapped his paws together. The man smiled up at me. “Like the circus,” he said, except he pronounced circus like seer-coos. I chose not to be offended that he just assumed I spoke English.

At home, I would have been frantically looking around for Creativity, tugging on the hem of her gown if I saw her pass by: Notice me, visit me! It would be tempting to do the same here; after all, it’s alluring to align your self-worth with productivity, and Creativity is a cousin of productivity. But that day, I released myself from the pressure of finding inspiration. I wasn’t seeking material for my next drawing or trying to sneak this man into my next essay. It was the first time I didn’t automatically assume that a change of scenery meant a boost in creating work.

And I delighted in that freedom. It felt like the day belonged only to me, so every walk was only for the pleasure of walking and a tree was just a tree; neither had any pressure to inspire me. That afternoon, my only obligation was to finish a coffee and find out which kid would win the game of tag going on before me.

Despite my overwhelming appreciation for the elegance of Bordeaux, there wasn’t a whole lot to do there, especially when it was too cold to spend much time outside. In most touristy areas there were posters and brochures for vineyard tours, but I assumed this was more of a summer/fall activity, not one for the dead of winter. Even so, strangers insisted I should go; I might get a private tour on the off-season.

Sure enough, that’s exactly what happened.

A taxi took me an hour outside of the city to the closest winery. I can’t tell you what made this one distinct to others but apparently it was very old and very good. That’s about as much as I could really glean from my French conversation with my driver, who had arranged the tour on my behalf.

I spent the next couple of hours with the vintner’s daughter, Genevieve, who looked a little irked that she had to spend her day out in the freezing vines with a clueless tourist.

Irked or not, she took me to places around the property where she wouldn’t normally bring groups, like the stables where they kept the Clydesdale horses who pulled the ploughs so the winemakers could avoid motorized engines and chemical weed killers. The horses looked like they came from a scene in a fantasy movie; they were so enormous, with big brown, knowing eyes and silver manes that swooshed back like they had superpowers. I came eye to eye with Charles, the patriarch, whose pink muzzle warmed my hand. He scratched his cheek on the wooden fence and it shook the ground.

After all, it’s alluring to align your self-worth with productivity, and Creativity is a cousin of productivity.

We took a long meander through the vines themselves, which looked like skeletons of mythical creatures with multiple arms and heads. I thought of the scary Greek serpentine water monster, the Lernaean Hydra, whose remains would perfectly resemble these spiky branches. I could hardly imagine what this land would look like in just a couple of months, but my heart lightened at the thought of it: edgeless waves of light green leaves spangled with juicy little grapes.

“What do you do during the winter?” I asked the increasingly amiable Genevieve, who had at some point resigned herself to the fact that she was stuck with me whether she liked it or not. “I mean with the vines?”

She looked at me with a furrowed brow like I had just asked her if I could take Charles out for a spin and answered, “Nothing.” I fully expected her to add a “duh” at the end.

I waited, and she continued. “Well, the workers prune the vines to keep them healthy.” Again, I imagined she added an “obviously” to that sentence. “But we’re in the cellar most of the time during the winter, bottling and working on sales.” She looked sternly at me as if to imply, Except when a tourist decides to come here in the middle of February.

Inside the cellar, she showed me a painting belonging to her grandparents, featuring the very vines I’d just walked through. It depicted a beautiful woman in a robe and crown pointing to the vineyard—the agriculture goddess Demeter, perhaps. She looked proud of the abundance that sprawled out across the canvas. However, the important part of this painting, Genevieve shared, was not the woman, but the tiny snail near the goddess’s foot—a reminder to the vintners that this could all go away in a relative instant if it fell into the hands of a particularly aggressive pest.

It all seemed so magically and terrifyingly precarious. An early frost or one little bug could destroy a year’s harvest. A few generations had devoted their lives to this particular vineyard, and a premature chilly day could throw it all out of whack. Genevieve told a clearly painful story about a year when the harvest was ruined, which resulted in far fewer bottles than surrounding years—making those bottles attractive to collectors now.

In Manhattan, while we grumble about having to pull out the parkas when we haven’t fully enjoyed wearing our trench coats, an entire team of workers in Bordeaux might be out of a job for a few months. We complain about winter nudging its way into fall a bit too enthusiastically, but for this family outside of Bordeaux, it’s close to life-and-death.

“This painting is very wise,” I told Genevieve when I studied the woman standing in front of the vines, as though she needed me to give an assessment. She nodded and we moved on.

The winemakers, devoted to their art, are constantly aware that conditions could destroy their tireless work, make the grapes scarce, or just skip over a harvest willy-nilly. But rather than obsessing over losing their crop, it seems to me that this awareness gives them more attentiveness and reverence for what they’ve already accomplished. Hence the proud woman in the foreground looking over her crop with awe.

Several months later, I took a yoga class in the fullness of New York summer. Summer in New York City is dense with the smells of steamed garbage and sudsy ammonia from laundromats. Walk by a fish shop and you feel like your senses are assaulted. My yoga studio wasn’t quite cool enough—nothing ever felt cool enough—and the stickiness of sweat under my sports bra put me in a decidedly non-yoga state of mind.

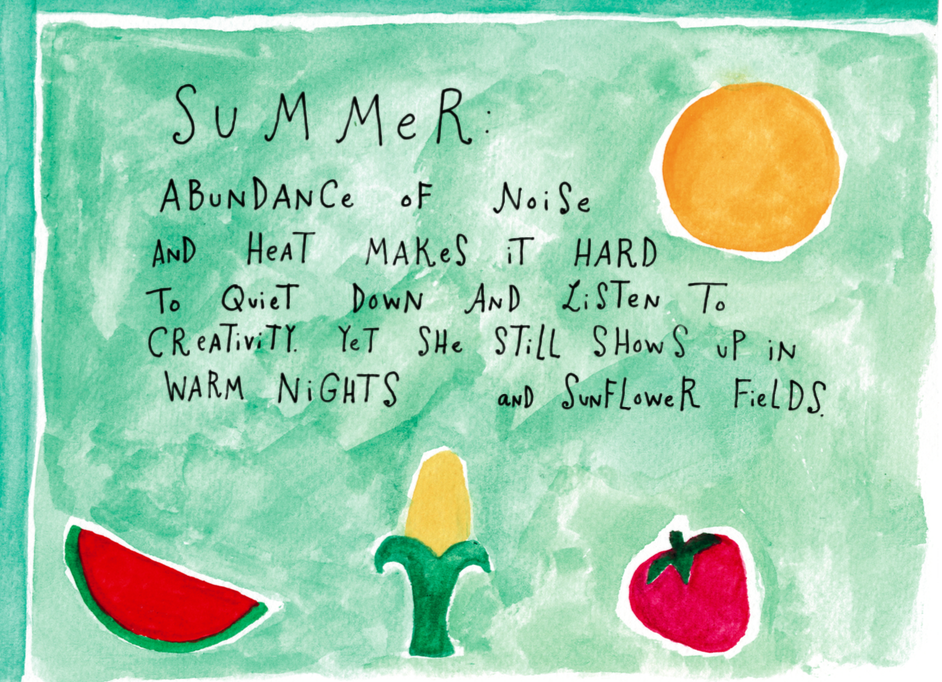

Moreover, I was dealing with a familiar hot-weather affliction: lack of ideas. My friend Creativity had seemingly taken the summer off, and my mind was mushy in the humidity. I was trying to summon Creativity back from her extended vacation by getting into a routine. For me, that usually involves physical activity. Thus, I committed to daily yoga, even if the short walk to my studio was excruciating in August’s heat.

When the teacher told us to close our eyes and imagine a happy place, I shifted around to different moments, mostly involving drinking foreign beverages. A cappuccino in Berlin? A sparkling water on a Greek island? With these memories at my fingertips, the sweaty sports bra complaint seemed a little bit ridiculous. It didn’t make it any less irritating, though. Good thing the mind and heart are expansive enough to be irritated and grateful at the same time.

After a couple moments of more mental fumbling, I eventually landed on the afternoon I sat outside drinking coffee and watching the world go by during my trip to Bordeaux. The yoga teacher asked us to think about how we felt in that moment, what made it feel so good right then. What came to mind was how much I appreciated my surroundings. In normal ho-hum life, you’re not usually thinking, “Wow, this coffee is so delicious and dainty, this man and his poodle are so charming, these children in peacoats playing tag are our future and I’m so endeared toward them.” You’re thinking, “Did I remember to buy cat food?”

I rolled the scene around in my mind. What made me appreciate those mundane little details with so much enthusiasm? Maybe I was on hyper appreciation mode because the sun was giving us only a sliver after many months of grey, and the trip wouldn’t last forever. Maybe I was on awareness overdrive because I knew the moment was fleeting. Who knew if I’d ever be in Bordeaux again? Maybe letting go of waiting for Creativity to visit gave me the permission I needed to treasure my surroundings. Every wisp of the scene felt precious: the children, the river, the mittens. Even winter had begun its lingering exit (not without saying good-bye to every single party guest and woefully outstaying its welcome).

My mental screen displayed the vineyard image next, and I thought about how the vines must be covered in soft green grapes this time of year. At least, I assumed so. I remembered how appreciative Genevieve was of her own work; she seemed to relinquish control to the vineyard rather than feign control over it. She wasn’t aggressive toward her vineyards; instead, she devoted her energy to sweetly caring for them and respecting the elements far beyond her control that have guided and turned their back on winemakers for millennia.

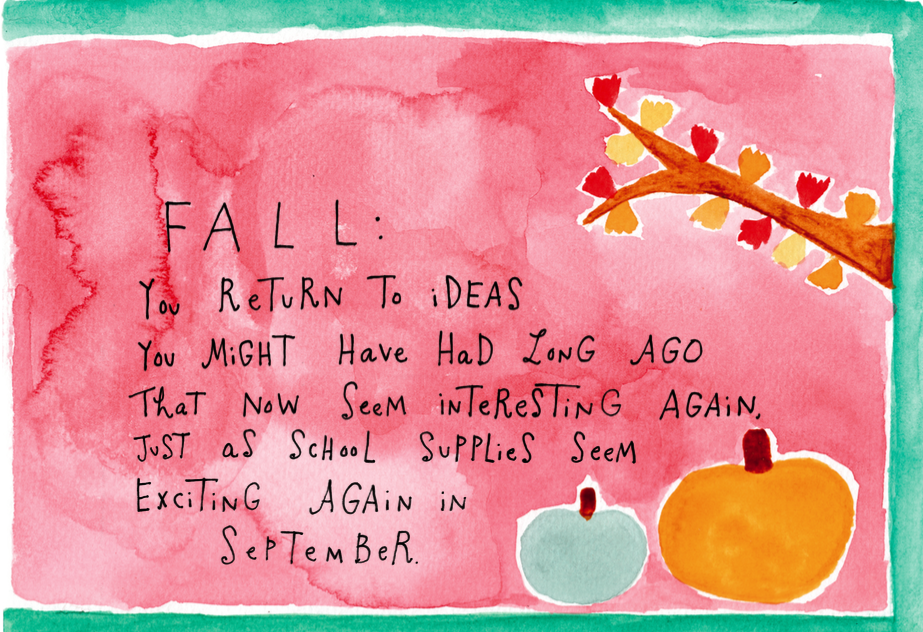

I thought about Creativity. I already knew she had a mind of her own, but what if I were more reverent toward her whims, like Genevieve was with her orchards? What if I treated Creativity not like a fickle friend, but like a vineyard, with the ancient steady presence of roots deeply grown?

You have to be reverent to go into the winemaking business. Grape growing is unpredictable and affected by many factors completely out of human control. For the winemakers, every year is a gamble. But every fall is also a victory: the farmers did all they could and the grapes provided—sometimes abundantly, sometimes less so. Either way, winemakers get back to work. They trust in the centuries-old soil, knowing that a break or a bad year won’t curse the vineyards into permanent deficiency.

The winemakers stand in awe of their vineyards, amazed by all they can withstand and all the delights they provide. This amazement is in no small part due to the fact that the harvest is unpredictable, but not unreliable.

Writers and artists and ceramicists and anyone else with an artistic bone in their body are told so often that they can create on demand, they often begin to believe it. I certainly did, in my less enlightened moments. But I’m learning that ideas are as wild and susceptible to weather as sweet, sensitive grapes; unpredictable, but not unreliable.

And each are deserving of reverence.

Reverence is the practice of remembering your place in the world: small, and with very little control. It sounds defeatist, but I think it’s actually the key to living with a sense of wonder and appreciation. Nothing was ever promised to us, including the miracle of life itself. To go through the world feeling entitled to such precious gifts like inspiration and creativity is just setting yourself up for a life of annoyance and rage. Treating Creativity like an unreliable friend—assuming she was out to deceive or abandon me—was not a reverent way to treat something so precious.

Revering Creativity would mean humbling myself in front of her power. She’s much older and wiser than any of us—even older than wise old trees and vineyards—and she will come visit when she wants. That means we have to pay attention, discipline ourselves to do good things with her, devote our time to her. Just as the winemakers showed up to tend to their grapes no matter what, creative people have to keep showing up and be patient when Creativity doesn’t meet them exactly when and where they want.

I could only hope for my own abundant harvest of ideas come September. Nonetheless, I vowed to appreciate the return of the seasons with all their different energies, new smells, and promise of an inevitable harvest—even if it didn’t yield much this year.

_____________________________________

From MY INNER SKY by Mari Andrew, published by Penguin Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2021 by Mari Andrew.

Mari Andrew

Mari Andrew is a writer, artist, and speaker based in New York City. She is the author of Am I There Yet? and posts her writing and illustrations on Instagram at @bymariandrew.