A strong response to the paintings of Edward Hopper is by no means uncommon, in America and throughout the world. But I’ve come to believe that it’s singularly strong among readers and writers—that Hopper’s work resonates profoundly with those of us who care deeply for stories.

And that’s not because of the stories his paintings tell.

Hopper was neither an illustrator nor a narrative painter. His paintings don’t tell stories. What they do is suggest—powerfully, irresistibly—that there are stories within them, waiting to be told. He shows us a moment in time, arrayed on a canvas; there’s clearly a past and a future, but it’s our task to find it for ourselves.

Contributors to In Sunlight Or In Shadow have done just that, and I’m gobsmacked by what they’ve provided. With original contributions from Stephen King, Joyce Carol Oates, Robert Olen Butler, Michael Connelly, Megan Abbott, Craig Ferguson, Nicholas Christopher, Jill D. Block, Joe R. Lansdale, Justin Scott, Kris Nelscott, Warren Moore, Jonathan Santlofer, Jeffery Deaver, Lee Child, and Gail Levin, along with one of my own, the stories are in various genres, or in no genre at all. Some of them spring directly from the canvas, making a story to fit the chosen painting. Others rebound at an oblique angle from the canvas, relating the story it somehow triggered. As far as I can make out, the stories have only two common denominators—their individual excellence and their source in Edward Hopper.

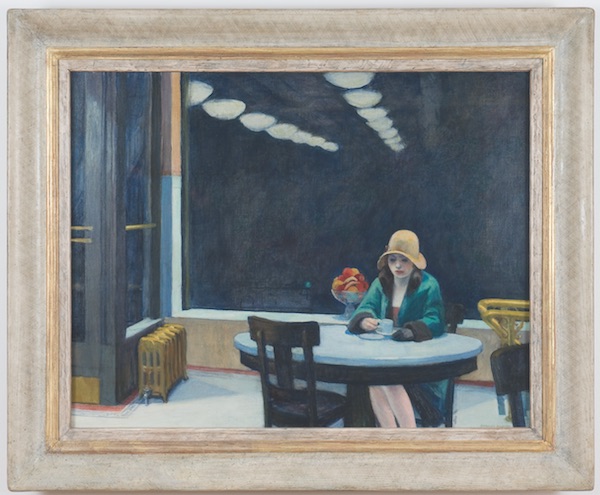

It’s been quite an exciting endeavor to undertake, and I think readers are in for a real treat. To give you a taste of the final product, here’s an excerpt of my own story—based upon Hopper’s 1927 painting Automat.

–Lawrence Block, New York, NY, December 2016

AUTUMN IN THE AUTOMAT

The hat made a difference.

If you chose your clothes carefully, if you dressed a little more stylishly than the venue demanded, you could feel good about yourself. When you walked into the Forty-second Street cafeteria, the hat and coat announced that you were a lady. Perhaps you preferred their coffee to what they served at Longchamps. Or maybe it was the bean soup, as good as you could get at Delmonico’s.

Certainly it wasn’t abject need that led you to the cashier’s window at Horn & Hardart. No one watching you dip into an alligator handbag for a dollar bill could think so for a minute.

The nickels came back, four groups of five. No need to count them, because the cashier did this and nothing else all day long, taking dollars, dispensing nickels. This was the Automat, and the poor girl was the next thing to an Automaton.

You took your nickels and assembled your meal. You chose a dish, put your nickels in the slot, turned the handle, opened the little window, and retrieved your prize. A single nickel got you a cup of coffee. Three more bought a bowl of the legendary bean soup, and another secured a little plate holding a seeded roll and a pat of butter.

You carried your tray to the counter, moving very deliberately, positioning yourself in front of the compartmented metal tray of silverware.

The moment you’d walked through the door you knew which table you wanted. Of course someone could have taken it, but no one did. Now, after a long moment, you carried your tray to it.

*

She ate slowly, savoring each spoonful of the bean soup, glad she’d decided against making do with a cup for the sake of saving a nickel. Not that she hadn’t considered it. A nickel was nothing much, but if she saved a nickel twice a day, why, that came to three dollars a month. More, really. Thirty-six dollars and fifty cents a year, and that was something.

Ah, but she couldn’t scrimp. Well, she could in fact, she had to, but not when it came to nourishing herself. What was that expression Alfred had used?

Kishke gelt. Belly money, money saved by cheating one’s stomach. She could hear him speak the words, could see the curl of his lip.

Better, surely, to spend the extra nickel.

Not for fear of Alfred’s contempt. He was beyond knowing or caring what she ate or what it cost her.

Unless, as she alternately hoped and feared, it didn’t all stop with the end of life. Suppose that fine mind, that keen intelligence, that wry humor, suppose it had survived on some plane of existence even when all the rest of him had gone into the ground.

She didn’t really believe it, but sometimes it pleased her to entertain the notion. She’d even talk to him, sometimes aloud but more often in the privacy of her mind. There was little she hadn’t been able to share with him in life, and now his death had washed away what few conversational inhibitions she’d had. She could tell him anything now, and when it pleased her she could invent answers for him and fancy she heard them.

Sometimes they came so swiftly, and with such unsparing candor, that she had to wonder at their source. Was she making them up? Or was he no less a presence in her life for having left it?

Perhaps he hovered just out of sight, a disembodied guardian angel. Watching over her, taking care of her.

And no sooner did she have the thought than she heard the reply. Watching is as far as it goes, Liebchen. When it comes to taking care, you’re on your own.

*

She broke the roll in two, spread butter on it with the little knife. Put the buttered roll on the plate, took up the spoon, took a spoonful of soup. Then another, and then a bite of the roll.

She ate slowly, using the time to scan the room. Just over half the tables were occupied. Two women here, two men there. A man and woman who looked to be married, and another pair, at once animated but awkward with each other, who she guessed were on a first or second date.

She might have amused herself by making up a story about them, but let her attention pass them by.

The other tables held solitary diners, more men than women, and most of them with newspapers. Better to be here than outside, as the city slipped deeper into autumn and the wind blew off the Hudson. Drink a cup of coffee, read the News or the Mirror, pass the time . . .

*

The manager wore a suit.

So did most of the male patrons, but his looked to be of better quality, and more recently pressed. His shirt was white, his necktie of a muted color she couldn’t identify from across the room.

She watched him out of the corner of her eye.

Alfred had taught her to do this. Your eyes looked straight in front of you, and you didn’t move them around to study the object of your interest. Instead you used your mind, telling it to pay attention to something on the periphery of your vision.

It took practice, but she’d had plenty of that. She remembered a lesson in Penn Station, across from the Left Luggage window. While she kept her eyes trained on the man checking his suitcase, Alfred had quizzed her on passengers queuing for the Philadelphia train. She described them in turn and glowed when he praised her.

The manager, she noted now, had a small, thin-lipped mouth. His wing-tip shoes were brown, and buffed to a high polish. And, even as she observed him without looking at him, he studied his patrons in quite the opposite manner, his gaze moving deliberately, aggressively, from one table to the next. It seemed to her that some of her fellow diners could feel it when he stared at them, shifting uncomfortably without consciously knowing why.

She had prepared herself, but when his eyes found her she couldn’t keep from drawing a breath, barely resisting the impulse to swing her eyes toward his. Her face darkened, she could feel it change expression, and when she reached for her coffee cup she could feel the tremor in her hand.

There he stood, beside the door to the kitchen, his hands clasped behind his back, his visage stern. There he stood, observing her directly while she observed him as she’d been taught.

There he was. With just a little effort, she managed to take a sip of coffee without spilling any of it. Then she returned the cup to the saucer and took another breath.

*

And what did she suppose he had seen?

She thought of a half-remembered poem, one they’d read in English class. Something about wishing for the power to see oneself as one was seen by others. But what was the poem and who was its author?

What the restaurant manager would have seen, she thought, was a small and unobtrusive woman of a certain age, wearing good clothes that were themselves of a certain age. A decent hat that had largely lost its shape, an Arnold Constable coat, worn at the cuffs, with one of its original bone buttons replaced with another that didn’t quite match.

Good shoes, plain black pumps. Her alligator bag. Both well crafted of good leather, both purchased from good Fifth Avenue shops.

And both showing their age.

As indeed was she, like everything she owned.

What would he have seen? The very picture of shabby gentility, she thought, and while she could not quite embrace the label, neither could she take issue with it. If her garments were shabby, they nevertheless announced unequivocally that their owner was genteel.

*

A man at the table immediately to her right—dark suit, gray fedora, napkin tucked into his collar to shield his tie—was alternating between sips of his coffee and forkfuls of his dessert, which looked to be apple crisp. She’d given no thought to dessert, and now a glimpse of it ignited the desire. She couldn’t remember the last time she’d had their apple crisp, but she remembered how it tasted, a perfect balance of tart and sweet, the crisp part all sugary and crunchy.

They didn’t always have apple crisp, which argued for her having a portion now, while it was available. It wouldn’t cost her more than three nickels, four at the most, and she still had fifteen of the twenty nickels the cashier had supplied. All she had to do was walk to the dessert section at the far right and claim her prize.

No.

No, because her cup of coffee was almost gone, and she’d want a fresh cup to accompany her dessert. And that would only cost a single nickel more, and she could afford that even as she could afford the dessert itself, but even so the answer was—

No.

The word again, in Alfred’s voice this time.

You are stalling, Knuddelmaus. It’s not the pleasure of the sweet that lures you. It’s the desire to postpone that which you fear.

She had to smile. If some corner of her own imagination was supplying Alfred’s dialogue, it was doing so with great skill. Knuddelmaus had been one of his pet names for her, but he had used it infrequently, and it hadn’t crossed her conscious mind in ages. Yet there it was, in his voice, bracketed with English words full of the flavor of the Ku’damm.

You know me too well, she said, speaking the words only in her mind. And she waited for what he might say next, but nothing more came. He was done for now.

Well, he’d said what he had to say. And he was right, wasn’t he?

Robert Burns, she thought. A Scotsman, writing in dialect sure to baffle high school students, and she’d lost the rest of the poem but the one couplet had come back to her:

O wad some Power the giftie gie us

To see oursels as ithers see us!

But really, she wondered, would anyone in her right mind really want such a power?

*

The man with the gray fedora put down his fork and freed his napkin from his collar, using it to wipe the crumbs of his apple crisp from his lips. He picked up his coffee cup, found it empty, and moved to push back his chair.

But then he changed his mind and returned to his newspaper.

She fancied she could read his mind. The restaurant was not full, and no one was waiting for his table. He’d given them quite enough money—for his chicken pot pie and his coffee and his apple crisp—to keep his table as long as he wanted it. They didn’t rush you here, they seemed to recognize that they were selling not just food but shelter as well, and it was warm here and cold outside, and it’s not as though anyone were waiting for him in his little room.

Or for her in hers. She lived a ten-minute walk away, in a residential hotel on East Twenty-eighth Street. Her room was tiny, but still a good value at five dollars a week, twenty dollars a month. She’d long ago positioned a doily on the nightstand to hide the cigarette burn that was a legacy of a previous tenant, and hung framed illustrations from magazines to cover the worst water stains on the walls. There was a carpet on the floor, sound if threadbare, and downstairs the lobby furniture might have seen better days, but didn’t that make it a good match for the residents?

Shabby genteel.

*

Two tables away, a woman about her age spooned sugar into her half-finished cup of coffee.

Free nourishment, she thought. The sugar bowl was on the table and you could make your coffee as sweet as you wished. The manager, who watched everything, no doubt registered every spoonful, but didn’t seem to object.

When she’d first begun drinking coffee, she took plenty of cream and sugar. Alfred had changed that, teaching her to take it black and unsweetened, and now that was the only way she could drink it.

Not that the man had lacked a sweet tooth. He’d had a favorite place in Yorkville with pastries he proclaimed the equal of Vienna’s Café Demel, and paired his Punschkrapfen or Linzer torte with strong black coffee.

You must have the contrast, Liebchen. The bitter with the sweet. One taste strengthens the other. At the table as in the world.

His words were strongly accented now. Vun taste strengsens ze uzzer. When she’d met him he was new in the country, but even then his English held just a trace of Middle Europe, and within a year or two he’d polished away the last of it. He’d allowed it to return only when it was just the two of them, as if she alone was permitted to hear where he’d come from.

And it was when he talked about the past, about times in Berlin and Vienna, that it was strongest.

She took a last sip of coffee. It wasn’t the equal to the strong dark brew he’d taught her to prefer, but it was certainly more than acceptable.

Did she want another cup?

Without shifting her gaze, she allowed herself another visual scan of the room, saw the manager look at her and then away, studied the woman whom she’d seen adding sugar to her coffee.

A woman dressed much as she was dressed, with a decent hat and a well-cut dove gray coat, neither of them new. A woman whose hair was graying and whose forehead showed worry lines, but whose mouth was still full-lipped and generous.

Now the woman was looking at her, studying her without knowing she was being studied in return.

Pick an ally, Schatzi. They come in handy.

She let her eyes move to meet the woman’s, noted her embarrassment at the contact, and eased it with a smile. The woman smiled back, then turned her attention to her coffee cup. And, contact established, she picked up her own cup. It was empty, but no one could know that, and she took a little sip of nothing at all.

*

You are stalling, Knuddelmaus.

Well, yes, she was. It was warm in here and cold out there, but it would only grow colder as afternoon edged into evening. It wasn’t the wind or the air temperature that made her reluctant to leave her table.

It was the fourth of the month, and her rent had been due on the first. She’d been late before, and knew that nobody would say anything until she was a week overdue. So there’d be a reminder in three days, a gentle advisory delivered with a gentle smile, directing her attention to what was surely an oversight.

She didn’t know what the next step would be, or when it would come. So far that single reminder had achieved the desired effect, and she’d found the money and paid the monthly rental a day after it had been requested.

That time, she’d pawned a bracelet. Three stones, carnelian and lapis and citrine, half-round oval cabochons set in yellow gold. Thinking of it now, she looked down at her bare wrist.

It had been a gift of Alfred’s, but that had been true of every piece of jewelry she’d owned. The bracelet was evidently her favorite, as it had been the last to make the trip to the pawnshop. She’d told herself she’d redeem it when the opportunity presented itself. She went on believing this until the day she sold the pawn ticket.

And by then she’d grown accustomed to no longer owning the bracelet, so the pain was muted.

We get used to things, Liebchen. A man can get used to hanging.

Could anyone speak those lines convincingly other than with the inflection of a Berliner?

And you are still stalling.

*

She put her handbag on the table, then was taken by a fit of coughing. She put her napkin to her lips, took a breath, coughed again.

She didn’t look, but knew people were glancing in her direction.

She took a breath, managed not to cough. She was still holding her napkin, and now she picked up each of her utensils in turn, the soup spoon, the coffee spoon, the fork, the butter knife. She wiped them all thoroughly and placed each of them in her handbag. And fastened the clasp.

Now she did look around, and let something show on her face.

She got to her feet. Not for the first time, she felt a touch of dizziness upon standing. She put a hand on the table for support, and the dizziness subsided, as it always did. She drew a breath, turned, and walked toward the door.

She moved at a measured pace, deliberately, neither hurrying nor slowing. This Automat, unlike the one closer to her hotel, had a brass-trimmed revolving door, and she paused to let a new patron enter the restaurant. She thought about the desk clerk at her hotel, and the twenty dollars. Her purse held a five-dollar bill and two singles, along with those fifteen nickels, so that she could pay a week’s rent and have a few days to find the rest, and—

“Oh, I don’t think so. Stop right there, ma’am.”

She extended a foot toward the revolving door, and now a hand fastened on her upper arm. She spun around, and there he was, the thin-lipped manager.

“Bold as brass,” he said. “By God, you’re not the first person to walk off with the odd spoon, but you took the lot, didn’t you? And polished them while you were at it.”

“How dare you!”

“I’ll just take that,” he said, and took hold of her handbag.

“No!”

Now there were three hands gripping the alligator bag, one of his and two of her own. “How dare you!” she said again, louder this time, knowing that everyone in the restaurant was looking at the two of them. Well, let them look.

“You’re not going anywhere,” he told her. “By God, I was just going to take back what you stole, but you’ve got an attitude that’s as bad as your thieving.” He called over his shoulder: “Jimmy, call the precinct, tell the guy on the desk to send over a couple of boys.” His eyes glinted—oh, he was enjoying this—and his words washed over her as he told her he would make an example of her, that a night or two in jail would give her more of a sense of private property.

“Now,” he said, “are you gonna open that bag, or do we wait for the cops?”

FOR THE REST OF THE STORY, SEE: In Sunlight Or In Shadow

Autumn at the Automat” by Lawrence Block is excerpted with permission from In Sunlight or in Shadow: Stories Inspired by the Paintings of Edward Hopper. Reprinted by arrangement with Pegasus Books. All rights reserved.