Excavating the Life of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, Author of an American Classic

The Writer of The Yearling Gets a Long-Deserved Biography

I first heard about Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings from my fourth-grade teacher at McNab Elementary in Pompano Beach, Florida. It was early spring, and Mrs. Chapman, a Florida native, decided it was a good time to share Rawlings’s best-known novel, The Yearling, with twenty nine-year-olds. Every day after lunch, for weeks, she read aloud a few pages, inviting the class to listen for the author’s beautiful sentences and the backwoods Florida world they brought to life. All of us, northern transplants whose families had been lured to the state by the postwar boom, were entranced by the story, delivered during that delicious drowsiness following milk and sandwiches by an old-timer whose voice was as soft and suggestive as distant radio waves.

The Yearling was our first impression of Old Florida, the peoples’ speech and traditions, and Mrs. Chapman’s reading seemed a private thing, a gift from her to us. We didn’t know that the book, a coming-of-age story about a boy, his pet deer, and his parents, who farmed the north-central Florida scrub, had been the best-selling novel of 1938. Nor did we know the book had won the Pulitzer Prize and been translated into 29 languages, or that Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer had made a popular film of it, starring Gregory Peck and Jane Wyman—all before we were born. By the time Mrs. Chapman read it to us, The Yearling had come to be thought of as a children’s book, because it centered on a young boy. It was a staple of the elementary school story hour.

I loved The Yearling as one loves a fairy tale or a dream, and Mrs. Chapman’s reading became one of my fondest memories. Much later, I read the novel by myself, silently, admiring it as magnificent storytelling, as literature. The novel’s lyricism, its fine rendering of country life, its use of local dialect, its structure and emotional range revealed Rawlings the artist, and I wanted to know how she, born in 1896, had become one. For clues, I took up her 1942 memoir Cross Creek, also a best seller in its day, and reveled in stories of the tiny Florida settlement where she’d established her writing career in the 1930s.

Cross Creek was the place out of which she wrote, no doubt a magical spot, and finally, I traveled to the area, which had changed very little since she’d lived there. The hamlet was still a rural community on a stream between two lakes, Orange and Lochloosa, altered only by the soft conversion of Marjorie Rawlings’s farmhouse, outbuildings, and orange grove into a state park with a paved road and guided walking tours. It was easy to imagine writing here. Still, I wondered, who was the artist whose life and work had made a shrine of this outpost? Where, beyond her two best-known books and Floridians’ sentimental tributes to her memory, was evidence of the complex woman Rawlings must have been?

In 2014, it seemed the only answer would be to pursue a biography of Rawlings—just one existed, and it was more than 25 years old. When I contacted Florence Turcotte, the archivist for the Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings Papers at the University of Florida, I asked if there would be enough material to work with. “No problem—it’s one-stop shopping here,” Flo said, and I quickly learned that the Rawlings archive is many-stops shopping, because the collection, including letters, manuscripts, news clippings, and photographs, is vast—which I found both reassuring and intimidating. Even so, I suspected there were more resources to be discovered, and in time, that suspicion proved correct.

While I relied on every possible source to create Marjorie’s portrait, two large bodies of work were critical. First, the more than 4,000 letters to and from Marjorie and her many friends, lovers, family members, and professional associates offer an extraordinary look into the writer’s public, private, and interior lives. Her writings contain descriptions of experiences in New York City, Rochester, Cross Creek, and other locations; reactions to books, articles, and political developments; encounters with other writers; reports on her uneven health; armchair analyses of pals, acquaintances, and employees; and gossip. Letter writing in her lifetime was a standard form of extended, long-distance communication. Depending on where one lived, telephone use was to various degrees limited and expensive, and at Cross Creek, even when phones were finally available, the service was spotty and complicated by party lines.

Marjorie wrote many letters longhand—and her hand was long: a bold, backhanded scrawl broken by extended dashes, as if she were speaking aloud, off the cuff. Possibly, she dashed off her boldest communiqués while drinking—a problem illuminated by her correspondence. Other letters were carefully composed and typed. Some read like set pieces worthy of a literary memoirist or a raconteuse, both of which she was. (Occasionally, some of these pieces or anecdotes appeared nearly word for word in letters to more than one person.)

But whether set down by hand or type, Marjorie’s letters are full-voiced, often performative. I might note here that quotations from the letters between Marjorie and Maxwell Perkins, her editor, and those from Marjorie to Norton Baskin, her second husband, reflect the punctuation decisions of Rodger L. Tarr, editor of Max and Marjorie: The Correspondence Between Maxwell E. Perkins and Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, and The Private Marjorie: The Love Letters of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings and Norton S. Baskin. Punctuation decisions for quotations from other letters are mine.

I have frequently treated her correspondence as I might handle interview material for a documentary. That is, I have listened for the most telling or significant lines, paragraphs, or whole letters to reveal various aspects of the author and the ways she expressed herself in conversation with others, as well as to establish facts. In 1998, when the George A. Smathers Libraries at the University of Florida acquired a rich cache of letters between Marjorie and her second husband, Norton Baskin, curator of manuscripts Frank Orser wrote: “As factual, detailed resources, they are the principal source for her biography, almost constituting an autobiography. As literature, they are often gems.” Marjorie herself would have agreed.

Toward the end of her life, in a speech given for the dedication of a new addition to the University of Florida library system, which would contain her papers, she remarked that “letters, particularly those of more than casual interest, I think, should be a very important part of the collection. Because anyone who has done research of any sort knows the treasure trove in coming across letters that picture the period and the personalities in a period far beyond the publications of the day.”

Two years later, as Marjorie researched a biography of novelist Ellen Glasgow and learned that Glasgow’s letters had been destroyed, she expressed deep disappointment: “This saddens me, as the very essence of a personality is often evinced in personal letters as in no other way.” Certainly she was thinking of her copious correspondence with Scribner’s editor Maxwell Perkins; her husbands, Charles Rawlings and Norton Baskin; and close friends like Julia Scribner Bigham, Macmillan editor Norman Berg, and writers including Zora Neale Hurston, Ernest Hemingway, and Sigrid Undset. With all, she shared her creative struggles. Without those letters, it would be impossible to tell how Marjorie got any writing done while running a productive orange grove and leading an increasingly public life—for she was, as soon as she left public relations and journalism work in the North for the Florida wilderness, a businesswoman and, after The Yearling’s success, a celebrity as well.

The second significant body of work, Marjorie’s two autobiographical manuscripts, nearly bookend her Florida writing years (her final novel, The Sojourner, was set in Michigan and largely accomplished in rural New York). The first manuscript, Blood of My Blood, is an account of her childhood, youth, and young adulthood; it stops at her mother’s death in 1923. She completed it after moving to Florida in 1928 and entered it unsuccessfully in a novel-writing contest. However, Blood of My Blood is more memoir than fiction, featuring her parents, brother, teachers, and others true to her life (all properly named) and focuses primarily on Marjorie’s difficult relationship with her mother, Ida Kinnan, whose ghost she needed to confront.

Though Marjorie excoriated her mother, barely redeeming her at the end, she admitted her own imperfections as a spoiled, manipulative child, understanding that she, too, was a flawed character. She wrote in the first and the third person, alternating intimacy and distance, and dramatized scenes like the saucy Hearst feature writer she had been, detailing physical surroundings with an observant journalist’s eye. Settings were geographically and historically grounded, individuals convincingly rendered. Peeling away the passion, the need, of this document, one can discern facts useful to a biographer. I have incorporated such information as confirmed by research, which included Marjorie’s later correspondence with her brother and other intimates.

However, passion itself is helpful: it divulges an author’s driving obsessions. (When she gave her papers to the University of Florida, Marjorie destroyed an earlier memoir, Diary of a Schoolgirl. “In my first year of college,” she wrote Clifford and Gladys Lyons—he was a professor at the University of Florida English Department and, later, at the University of North Carolina—“I had set out to re-write a perfectly honest diary of adolescent days, with literary intent. I remember having destroyed the original diary, quite certain that I had achieved a masterpiece of memoir in the re-writing. The early one would probably have been fun, but I hope the edited version never even caught the eye of God.”)

The second manuscript, Cross Creek, published in 1942 and as much a classic as The Yearling, is a creative nonfiction chronicle of Marjorie’s life at the Creek, a succession of graceful, sometimes humorous narratives describing encounters with friends, neighbors, farmhands, wildlife, weather, and flora and fauna. It is a treasury of true people, places, and events, meticulously, imaginatively, and urgently drawn. (It is not to be confused with the 1983 movie Cross Creek, an account of Marjorie’s early struggles to write in Florida.)

Besides Marjorie’s letters and memoiristic manuscripts, the various drafts and published versions of her work, from juvenilia to The Sojourner, offer a close look at her development as a writer, including themes and character types (such as the desire for home and the preadolescent boy) that persisted throughout her career. However, this biography is not intended as a work of literary criticism. I very much concur with Jeanette Winterson’s warning against “tying in the writer’s life with the writer’s work so that the work becomes a diary; small, private, explainable, and explained away, much as Freud tried to explain art away.” I seek to illuminate instead Marjorie’s humanity: her heart and mind.

To some extent, writers reflect who they read. Although Rawlings’s personal library was scattered after her death, one can trace her voracious reading habits in her letters. She was interested in so much: literature, politics, history, science, philosophy, biography, the art of writing. She loved Proust and detested Faulkner. She read and reread the Bible, although she was not religious in any conventional sense. She often consulted William Bartram’s 18th-century Travels, particularly the naturalist’s observations of Florida. She took on massive histories, dwelled on single poems. She once said she read “about a book a day.” I have included her reactions to certain books when they seemed directly connected to writing projects.

Also critical to understanding Rawlings are the times in which she lived. Although she aspired to write literary stories and novels, she was a woman of limited means, and directly after college, she needed to find a job—any job. Hoping to use her writing skills, she started out as a YWCA publicist. This led to a spotty journalism career in the 1920s, when women reporters were rare, mostly freelance, and assigned lightweight features for the new “women’s pages,” which multiplied after women gained the vote. In this, she was rewarded for facile storytelling, a natural ability her University of Wisconsin professor William Ellery Leonard warned her against, and with which she would struggle when writing serious fiction.

In the years containing most of her Florida output, 1930 through 1945, she was profoundly a writer of her time. During the Great Depression and leading up to World War II, a significant number of American authors chronicled, in fiction and nonfiction, culturally isolated corners of the country that hadn’t been changed by modern life. Some writers felt an anthropological impulse, the field burgeoning in response to studies such as Margaret Mead’s ground-breaking Coming of Age in Samoa and personal narratives like Luther Standing Bear’s My People the Sioux, both published in 1928. This urge teamed naturally with investigative reporting, a practice just a few decades old, which would lead to what is now referred to as immersion or participatory journalism—the reporter fully involving herself with a situation, sometimes incognito. Other writers were moved by America’s long-standing rural ideal, increasingly worshipped, feared for, or nostalgically mourned in the wake of the Industrial Revolution and the First World War. Some southern authors, notably Erskine Caldwell, worked to reveal the “waste land” and the “unknown people” of the rural South, characterizing them (white or black) as pitifully backward and judging their lack of connection to contemporary civilization. Such writers considered themselves agents of social change.

It is no accident that in Margaret Mead’s and Luther Standing Bear’s signal year—1928—the Library of Congress established the Archive of American Folk-Song, sending pioneering folklorist John Lomax and his son Alan on expeditions to gather authentic folk songs before traditional tunes could be overridden by radio’s new Billboard hits. Following that, the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Writers’ Project, established in 1935, deployed hundreds of writers from coast to coast to document regional American life. On the popular front, Fortune magazine sent writer James Agee and photographer Walker Evans to Alabama for six weeks to live with the families of three tenant farmers, their material finally appearing in book form as Let Us Now Praise Famous Men in 1941. And the southern literary renaissance was in full swing. Thomas Wolfe (Look Homeward, Angel, 1929) and William Faulkner (The Sound and the Fury, 1929) were among those who pulled away from romances about the antebellum South and responded to southern culture after the Civil War. Among the renaissance landmarks was Julia Peterkin’s Pulitzer Prize for her 1928 novel, Scarlet Sister Mary, which portrays black folklife in South Carolina’s Lowcountry. Peterkin was the first southern woman writer to win the prize.

It so happened that in 1928—the year of Peterkin’s win, Mead’s debut, and the folk song archive’s founding—Marjorie Rawlings decided to leave city newspaper work in Rochester, New York, to try writing fiction in Cross Creek, Florida. With a small inheritance, she bought, sight unseen, a 72-acre orange grove and farmhouse, determined, along with her first husband, Charles Rawlings, to write in deep, undocumented country full-time, living on citrus profits. As it turned out, the grove required far more labor than she had imagined—a saga in itself—yet Marjorie also saw in backwoods Florida a striking opportunity to immerse herself in a little-known culture and transform reporting into literary fiction. Within a few years of her arrival in north-central Florida, she had put the region, and herself, on the national literary map.

__________________________________

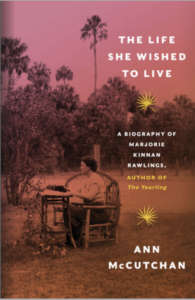

Excerpted from The Life She Wished to Live: A Biography of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, author of The Yearling. Copyright (c) 2021 by Ann McCutchan. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.