Every Coming-of-Age Story is an Apocalypse Story

Andrew DeYoung on Despair and Hope in the Edgelands of Adulthood

I was a freshman in college on 9/11, and I obtained what I still think of as my first real “grownup” job not long before the Great Recession of 2008. I share these facts not because they are unique, but precisely because they are not. Millions of people about my age share their own versions of the same stories. The concept of a “generation” is as arbitrary and dubious a sorting mechanism for human beings as personality types or zodiac signs, but the idea has one thing going for it: a generation, at the very least, gathers together a group of people who experienced the same cultural cataclysms at roughly the same stage in their development.

Each generation, in short, is defined partly—maybe even largely—by the apocalypses, the world-remaking catastrophes, it experienced somewhere in the cusp between adolescence and adulthood. The Boomers got duck-and-cover, Vietnam, and the convulsions of the 60s; Gen X had the Challenger explosion, the sputtering wind-down of the Cold War, Desert Storm on CNN. My generation, the Millennials, got 9/11 and the subsequent catastrophes of the Bush years. Gen Z is getting Covid-19, the global decline of democracy, the unmistakable signs of climate change, and… well, maybe the actual end of the world?

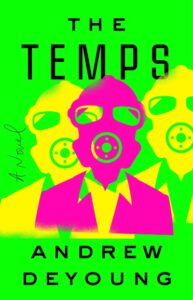

It’s increasingly impossible to talk about growing up in the 21st century without also talking about the end of the world. In 2022, every coming-of-age story is an apocalypse story. When I began to write The Temps, my own novel of disillusioned early adulthood, I naturally looked to the apocalypse genre in part because the fear that the world was ending was such a large part of my own protracted passage into adulthood. I still remember the clear sky that stretched above me on the day after the towers fell, meeting on the lawn with new friends I’d met at freshman orientation, wondering together if it was World War 3, if we’d be drafted to fight, if we were soon going to die in a war whose purpose we didn’t yet understand, and never would.

The apocalypse we envisioned didn’t come to pass, but it was an apocalypse all the same, and when we graduated four years later I emerged into a nation tattered by unending war, paranoia, and images of American torture. A few years after that, there was the corner conference room we met in as the American economy unraveled atop a crumbling housing market, me and the other entry-level lackeys wondering what would become of us, if we’d soon look back at our paltry scraping-by paychecks as a memory of lost abundance.

There would be more catastrophes to come, but there’s something about the apocalypses that occur as you stand at the cusp of adulthood. They’re the apocalypses that reveal the shape of the world you’re about to inherit. I can’t help but sympathize with the generations younger than mine, those entering adulthood in the age of Trump, the pandemic, January 6, and the imminent impacts of climate change—catastrophes both here and still coming. I look at the apocalyptic style of a young climate activist like Greta Thunberg and I can only admire the clarity of her urgency and rage. Climate change is my disaster, too—it belongs to all of us, every human who lives on Earth—but to Thunberg’s generation it must hold a special kind of despair. They’re only just getting started living their lives, and they find out the world they’re inheriting seems to be ending.

But if the apocalypse in coming-of-age can lead to despair, it can also reveal a way through our looming global disasters, and even a sense of hope. Contrary to the popular use of the term, apocalypse in its original meaning refers not to the end of the world, but to the revelation or unveiling of a world to come. One world ends, another begins—the one revealed by the apocalyptic event. In a coming-of-age story, the world that ends is the sheltered, innocent world of childhood; the one that is revealed is the hostile, dangerous, and hypocritical world of adults.

It’s increasingly impossible to talk about growing up in the 21st century without also talking about the end of the world.

To those who grow up as they’re happening, our cultural apocalypses reveal the nature of the adult world they stand to inherit. For my generation, 9/11 revealed a world of terrorism, violent American imperialism, and endless war. The 2008 crash revealed a world of inequality and reduced economic expectations just now coming to collect in the broad realization that millennials didn’t kill the economy—it killed us.

There seems to be an escalation in our recent apocalypses, though, in that the world they reveal seems at times to be coming to a true end: the end of democracy, the end of life on Earth. But if it’s true that every coming-of-age story is an apocalypse story, then it might also be true that every apocalypse story is a coming-of-age story—that is to say, that human civilization is not reaching an end but undergoing a turbulent adolescence, perhaps even growing up.

I’m struck by a trend of recent novels built of braided narratives scattered across time, which imagine distant realities beyond expected “in a not so distant future” apocalypses. Among these novels is Matt Bell’s Appleseed, Monica Byrne’s The Actual Star, and Anthony Doerr’s Cloud Cuckoo Land. These are tripartite narratives, evoking coming-of-age in their structure: a sheltered childhood containing seeds of a rocky pre-apocalyptic adolescence, followed in the distant future by a post-apocalyptic adulthood, a world wizened by bitter experience.

Though each of these writers predicts hard times to come for life on Earth, these books nonetheless strike me as hopeful in the sense that they are capable of imagining a future beyond the catastrophes that seem to be awaiting us, a future more generative than the wasted post-apocalyptic landscape of, say, Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. Though, you have to sometimes squint to see the optimism. In Bell’s Appleseed, the future has been winnowed down to one living being who might not even be human; in Doerr’s Cloud Cuckoo Land, the human future similarly seems to come down to one person, the sole survivor on a generation ship searching for a new planetary home.

If the apocalypse in coming-of-age can lead to despair, it can also reveal a way through our looming global disasters.

Monica Byrne’s vision, in The Actual Star, may be the most genuinely optimistic—and it centers, tellingly, on a coming-of-age narrative. The middle time period of Byrne’s novel tells the story of a 19-year-old girl named Leah, whose sexual and spiritual coming-of-age in 2012 coincides with the end of the Mayan calendar: a date of predicted apocalypse. What happens to Leah (really, you’ll just have to read the book!) provides the basis for a new religion that shepherds humanity through a series of natural and political catastrophes, and ushers them into a utopian society described in the novel’s lattermost narrative: a global order predicated on borderlessness, nomadism, and a radical fluidity of personal identity and familial and communal relationships. Byrne’s name for the era of cataclysm that lies between here and there is the “Age of Emergency.” I’m drawn to the emerge in emergency, which is conceptually similar to the notion of an apocalypse as revelation. Both are a coming-to-light, information contained within disaster. What emerges from Byrne’s Age of Emergency is the shape of a utopia to come, guided by the example of a woman on the apocalyptic cusp of adulthood.

Coming-of-age narratives crop up all over apocalypse literature, when you really start to look for them. Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents centered on a young Black woman leading the world through apocalypse toward a new way of being in the world beyond capitalism, patriarchy, and racism. McCarthy’s The Road is about a father and son, and concerns the son’s education in post-apocalyptic survival.

And Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven—the headwaters of the apocalyptic publishing trend, the book that launched a thousand comps—contains a pair of coming-of-age threads amongst its host of narratives and characters: two children growing up in a catastrophic pandemic. The first is Kirsten, who survives the pandemic and later joins a group of wandering Shakespearean actors called The Travelling Symphony. The other is Tyler, or the Prophet, a troubled boy who becomes a cult leader and antagonist to the Symphony. These coming-of-age threads are heightened in the HBO adaptation of the book, in which Kirsten and Tyler comprise a dialectic, a push-and-pull on the question of what should be done with the world of the adults, the Before, the past: preserve something good from it, or burn it to the ground. Both are influenced by a graphic novel, a contested inheritance from a shared father figure: for Tyler, an absent father; for Kirsten, a surrogate one. (There is an abundance of parent/child pairings in the series adaptation.)

Present in this push-pull are a host of other dialectics critical to the human future in the face of apocalypse: youth and adulthood, self and community, freedom and responsibility, past and future, preserving and dismantling, looking back and moving forward. Ultimately, both Mandel’s book and the television adaptation don’t so much resolve these tensions as push them toward an uneasy but hopeful truce, in which all that is good is preserved—including the revolutionary imagination needed to build a world that looks different than the one left behind.

If there’s any applicable insight here, it’s that we should probably look to those caught in the teeth of their own coming-of-age stories—people like Leah, and Kirsten—to help us weather our collective societal coming-of-age. In the midst of upheaval, the ones who can see the way forward most clearly are the young: removed enough from the protections of childhood to clearly perceive the magnitude of the problems facing us, but not yet so blinkered by the compromises of the adult world that they cannot see past the limitations of our current cultural arrangements to the possibility of a better future. All we have to do is let them tell their stories—to tell us about their apocalypses, both personal and communal, and about the world, waiting to be born, that their stories reveal.

It’s worth pausing here to observe that older generations often talk about emerging generations as though they are not a solution for apocalypse, but an apocalypse themselves. The young are always too immature, too sensitive, too radical, too angry—and too little invested in the systems and ideas society is built on. They’re going to change everything, the grownups tend to say, with fear in their voices. They’re going to end the world.

But to this kind of apocalypse—this revelation, this emergence—we must find a way to say: Yes. Bring it on.

___________________________

Andrew DeYoung’s The Temps is available for pre-order from Keylight Books.

Andrew DeYoung

Andrew DeYoung is the author of The Temps, a speculative novel about the end of the world. He works as an editor at a childrens book publishing company, and he lives with his wife and two children in the Twin Cities area in Minnesota. The Day He Never Came Home is his first domestic thriller.