Even in His Retirement, Philip Roth Wrote Thousands of Pages

Benjamin Taylor on Stoicism and Scandal in the Life of

an American Icon

To say Philip Roth stopped writing is inaccurate. He stopped making art. But his old way of coping with any embattlement, to sit down to the keyboard, continued in the years of his retirement. The underside of his greatness swarmed with grievances time had not assuaged. He couldn’t stop litigating the past and produced over a thousand pages of—well, what to call it?—self-justification in those years, all of which I read.

He’d been giving me typescripts and manuscripts since we met, a habit that accelerated. Sometimes these would be birthday gifts, sometimes gifts for no occasion. Sometimes he’d make jokes about the market value of such items when he inscribed them: “For your old age!” Sometimes he’d rather solemnly address me as if I were his archivist.

On one occasion he handed me a full-scale book called “Notes for My Biographer,” which would shortly be announced for publication before being withdrawn. The text is a point-by-point effort, frequently self-deceiving, to refute all of Claire Bloom’s charges against him in Leaving a Doll’s House, whose publication Philip counted among the worst catastrophes of his life and credited with his failure to win the Nobel. She’d assailed him and he needed to defend his moral reputation, pocked and homely though it was.

Another typescript, entitled in some copies “Notes on a Scandal Monger,” sought to even the score with his earliest anointed biographer and afterward ex-friend, Ross Miller, dedicatee of The Human Stain, who he felt had betrayed him by failing to work effectively and in a timely way on the project. People who should have been interviewed died off while Ross dithered. This is the sad tale of someone handed a job for which he was ill-equipped. And then featured as a villain. Ross was no villain, only a literary amateur, and it pained me to hear Philip go on about him as if he were Iago. “You cast him in a role much too large,” I said more than once. “He wasn’t malevolent, only not up to the task.” But as with Maggie and Claire and Francine, so with Ross: The appetite for vengeance was insatiable. Philip could not get enough of getting even.

He gave me both these bulky typescripts, the fruits of his retirement. After withdrawing “Notes for My Biographer,” he asked me to destroy my copy. I returned it to him instead. “Notes on a Scandal Monger” (it does not bear this title in my version) I kept with the mass of other documents in my Roth file.

What to do with such things when an author dies? There are essentially three possibilities: You can throw them away. You can leave them to the misunderstanding or neglect of heirs. Or you can get them to an institution that knows how to care for such things. I deeded my entire collection to the Manuscripts Division of Princeton’s Firestone Library. Parting with it put a calm in me. I knew the papers would be secure for as long as Princeton stood, as safe there as if they were Whitman’s or Melville’s.

It was the start of a history that would lead from surgery to surgery, including three spinal fusions in the last fifteen years of his life.

Notable in Claire Bloom’s bill of particulars was her allegation that Philip’s ailments were sometimes imaginary. But I was one of his medical proxies and can testify that they were all terrifyingly real and that his stoicism in the face of them was beyond what I, whose rude health he admired and teased me about, could have summoned. Still, there were limits. He liked to quote an unemphatic line from Hemingway’s “The Snows of Kilimanjaro”: “He could stand pain as well as any man, until it went on too long, and wore him out.”

It was in basic training at Fort Dix that a first and lasting injury befell him. “Another grunt and I were on KP and carrying a large kettle of potatoes. He dropped his end, causing me to wrench my back. I saw stars and felt a searing pain. It was this injury that led to my honorable discharge after one year.”

“You know, when my father died I wanted an honor guard at his funeral. They asked first to see the discharge. I looked in drawer after drawer and file after file and finally I found it in his billfold. He’d been carrying it on his person since the autumn of ’45.”

“I understand that perfectly. Whatever else lay ahead, I felt my honorable discharge was a plaudit that could never be taken from me—however lamed I was, arriving at the University of Chicago the following year in agony and with a back brace under my Brooks Brothers suit.”

It was the start of a history that would lead from surgery to surgery, including three spinal fusions in the last fifteen years of his life. He said the third, which restored an inch or two of the height he’d been losing, made him feel he was carrying inside himself a replica of the Eiffel Tower.

I’d been instructed beforehand to test his recall after each of the anesthesias. More than anything he feared cognitive loss. “Philip, who was FDR’s Secretary of Labor?” I asked him in recovery.

“Frances Perkins.”

“And of the Interior?”

“Harold Ickes.”

“Remember his middle initial?”

“L.”

“You’re all there.”

He then proceeded to his usual test of himself, the prologue to The Canterbury Tales: “Whan that Aprille with his shoures soote / The droghte of Marche hath perced to the roote,” and so on for some lines more.

Prescribed painkillers in ever larger doses produced expectable results. The fentanyl patch he wore was crazy-making. In combination with other culprits it drove him over the edge. One night in the country, at about three o’clock in the morning, he entered the guest bedroom and said, in tears, “Ben, can you find out for me if I’m awake or asleep? Can we call somebody to find out?” I walked him back to his room and stayed till sunup.

Withdrawal from fentanyl and other narcotic analgesics would be the great unspoken trial of Philip’s old age, an additional illness.

Add to it the epic struggle with heart disease. When told in 1982 that he had a fraction of normal cardiac function, he began the ritual of putting all his work in clear order at the end of each working day, not knowing if he’d return. “I was more afraid for the work in progress than for myself,” he told me. He kept the knowledge of this Damoclean sword almost entirely to himself. The humiliation of impotence, a side effect of the beta-blocker he was given, was not the least of his anguish. He begged for bypass surgery but was repeatedly told he was not a candidate.

Then in August of 1989, at 56, after swimming only the first of his afternoon laps, he felt overwhelmed and in immediate peril and wondered if he might actually precede his dying father to the grave. Twenty-four hours later, a quintuple bypass was performed at New York Hospital. Philip felt newborn. “I would smile to myself in the hospital bed at night,” he writes in Patrimony, “envisioning my heart as a tiny infant suckling itself on this blood coursing unobstructed now through the newly attached arteries borrowed from my leg. This, I thought, is what the thrill must be like nursing one’s own infant—the strident, dreamlike postoperative heartbeat was not mine but its.” There in the ICU he’d won the goal of happiness complete. He was free of the time bomb that had been ticking in his chest.

This new leasehold was also the proximate cause of a creative rebirth, probably the greatest in American literary history. What followed the experimentation of The Counterlife and Deception (a minor, radio play–like novel completed shortly before his bypass) was a sequence of masterpieces: Patrimony, Operation Shylock, Sabbath’s Theater, American Pastoral, I Married a Communist, The Human Stain, The Dying Animal, The Plot Against America, Everyman, Indignation, Exit Ghost and more, including his masterly last bow, Nemesis.

Further cardiac procedures followed. In 1998, he was back at New York Hospital for renal artery angioplasty and insertion of a stent. The following year, his left carotid artery was opened. A year after that came another angioplasty and stent insertion. In 2003, he was transferred in terrible pain from Charlotte Hungerford Hospital in Torrington to Lenox Hill Hospital in Manhattan, an event he loved describing: the rickety old ambulance, the bumpkin drivers. They’d never been to New York and Philip had to shout directions the whole way. They unloaded him, still in a hospital gown and on his gurney, at Lexington and Seventieth. “Is this neighborhood safe?” they asked. Curious passersby stopped to stare. Only the usual autograph hound was lacking. This indignity went on for fifteen long minutes before the drivers figured out that Lenox Hill was one block over and six up.

Next day, a defibrillator was installed, a raised rectangle about the size of a pack of cigarettes under the skin of his chest. “What do I need this thing for?” he used to say, skeptical of its merits. “I need this thing like a bus needs a parachute.” Then one evening he fibrillated and the thing went off, knocking him for a loop and restoring his heartbeat. He got the picture of what it was for, even grew fond of it. When the mechanism wore out and had to be replaced he said he was going to sell the old one on eBay. “Could get a pret-ty penny for it.”

Philip required more and more angioplasties and stents. Then, in 2013, it became clear that his ramus and LAD arteries were completely occluded. He was once again a walking bomb. Three or four interventions reopened both. Further interventions were required to reopen them yet again.

His doctors never felt these were losing battles. Cardiologists are optimistic, can-do people and Philip’s were among the best. In September of 2016 his aortic valve was replaced with either a bovine- or porcine-based substitute. I could never get that part straight. I asked in some trepidation about the body rejecting such tissue and was told the chances were zero. For some reason though, the idea of a piece of pig or cow in his heart kept me up nights.

I should have been worried about other things. The recuperation did not go smoothly. By early November he was back in New York-Presbyterian to treat blood clots that had formed on the leaflets of the new valve. On the evening of November 8, I breezed in with the word on the street: It would be an early night with Hillary taking Florida and Pennsylvania and Michigan.

He gave me a torpid look and said, “I’m scared.”

__________________________________

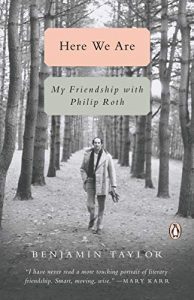

From Here We Are: My Friendship With Philip Roth by Benjamin Taylor, to be published in May by Penguin, an imprint of the Penguin Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC Copyright (c) 2020 by Benjamin Taylor.

Benjamin Taylor

Benjamin Taylor‘s memoir, The Hue and Cry at Our House won the 2017 Los Angeles Times/Christopher Isherwood Prize for Autobiography and was named a New York Times Editors’ Choice; his Proust: The Search was named a Best Book of 2015 by Thomas Mallon in The New York Times Book Review and by Robert McCrum in The Observer (London); and his Naples Declared: A Walk Around the Bay was named a Best Book of 2012 by Judith Thurman in The New Yorker. He is also the author of two novels, Tales Out of School, winner of the 1996 Harold Ribalow Prize, and The Book of Getting Even, winner of a 2009 Barnes & Noble Discover Award, as well as a book-length essay, Into the Open. He edited Saul Bellow: Letters, named a Best Book of 2010 by Michiko Kakutani in The New York Times and Jonathan Yardley in The Washington Post, and Bellow’s There Is Simply Too Much to Think About: Collected Nonfiction, also a New York Times Editors’ Choice. His edition of the collected stories of Susan Sontag, Debriefing, was published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux in November 2017. He is currently under contract to Penguin for a sequel to The Hue and Cry at Our House. Taylor is a founding faculty member in the New School’s Graduate School of Writing and teaches also in the Columbia University School of the Arts. He is a past fellow and current trustee of the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation and serves as president of the Edward F. Albee Foundation.