First Episode

“What’s with you? Tired?”

“Pissed.”

“About what?”

“The boss! Dirty bloodsucker—a florin and a half to load and unload two carts.”

“Can’t say as I blame you.”

The above conversation (which was spoken, like those following it, in a dialect I’ve altered and modified as best I could, so that readers, if this story ever has any readers, would understand them) took place in Trieste in the last years of the nineteenth century. The speakers were a man (a day laborer) and a boy. The man was sitting on a pile of flour sacks in a warehouse on via——. He was wearing a large red kerchief around his head, which hung below his shoulders (to protect his neck from the chafing fabric of the sacks). Though he seemed tired to Ernesto, he was a young man with a Gypsyish look about him—though an attenuated, tame kind of Gypsyness. Ernesto was sixteen and an apprentice at a company that bought flour from large Hungarian mills and sold it to the city’s bakeries. He had soft, curly chestnut hair and hazel eyes (like some poodles). Somewhat gangly, he moved with adolescent grace, as though he felt awkward and was afraid of being ridiculed. At the moment, he was leaning against the open door of the warehouse awaiting a cart due momentarily with the last load of the day. Although he knew the man well—he had been talking to him for months because they worked together and because he rather liked him—he was staring at him now, as if he were seeing him for the first time. Sitting there with his head cupped between his hands, the man looked exhausted to Ernesto. But the man said he was angry.

“Can’t say I blame you,” Ernesto repeated. “He’s a bloodsucker, the boss. I hate him too.” (But just one look at the boy made it seem unlikely that he really hated anyone.) “It makes me sick when he sends me out to the piazza to get a man to help, and he tells me what he’s going to pay. I get you all the time, but I’m always ashamed the money’s so little. I hate doing that.”

The man relaxed his tense posture and looked tenderly at Ernesto. “I know you’re okay,” he said. “If you ever get to be a boss, like I hope you do, there’s no way you’ll treat your workers the way this guy treats me. A florin and a half for three loads,” he said again, “and for two men. The crook gets away with murder. He’s got no idea what it means to work till you’re nearly dead, specially now that it’s getting hot. Even two florins a man wouldn’t be overpaying. If you weren’t here and I didn’t like talking to you, I wouldn’t be waiting for the cart. I’d be out of here in a flash and home in bed.”

It was a late-spring day and the street was filled with sunshine. But inside the warehouse the air was cool—cool and damp and smelling of flour.

“Why don’t you sit down?” the man asked after a brief silence. “Over here.” (He pointed to a spot close to himself.) “If you’re worried about getting dirty, you can sit on my jacket.” And he got up to get the jacket, which he had removed while awaiting the cart.

“I don’t need it,” Ernesto answered. “Flour doesn’t leave a mess. You just dust it off and it’s gone. And I don’t care if anyone sees it or not.” He stopped the man from spreading the jacket, and smiling, sat down beside him. The man was smiling too. He no longer looked tired or angry.

“If you want,” he said, “I’ll dust you off afterward.”

They sat in silence for a while, just looking at each other.

“You’re okay, kid,” the man said again, “and good-looking—really good-looking, easy on the eyes.”

“Me, good-looking?” Ernesto laughed. “No one’s ever said that to me.”

“Not even your mother?”

“Her least of all. I don’t remember her kissing me, or even hugging me. She always said you shouldn’t spoil children. Still says it.”

“You’d have liked your mother to kiss you?”

“Sure, when I was little. Now it doesn’t make any difference. I’d like it if she’d at least say something nice about me once in a while.”

“She doesn’t do that either?”

“Never,” Ernesto answered, “or hardly.”

“It’s too bad I haven’t got any money or decent clothes,” the man said.

“Why?”

“If I did, it would be nice to be your friend—for us to go walking together some Sunday.”

“Well, I’m not rich, either,” Ernesto said. “Do you know how much I make?”

“No, but you’ve got parents, and they must have money. How much do you make?”

“Thirty crowns a month and I give twenty of them to my mother. She buys my clothes.” (Ernesto wore ready-made clothes, and though he didn’t like admitting it, he would have liked to dress well—as some of his old school friends had.) “So there’s not much left for me.”

“But you’re learning a business in the meantime.”

“I don’t like working for anyone,” Ernesto replied. “I’d like doing something completely different.”

“Like what?”

The boy didn’t answer.

“So how do you spend the ten crowns you got left? On women?” (These last words were spoken as if the man feared an affirmative response.)

“I don’t go with women yet. I decided to keep away till I’m eighteen or nineteen.” (Perhaps he had forgotten that, two years earlier, his mother had had to fire a young kitchen maid, whom he was continually harassing. After that episode the poor woman had, as a precaution, hired only old misshapen or deformed women. She’d put together a real collection of gorgons. Even so, they didn’t last long. After a month or two, they quit or were fired.)

“And you?” Ernesto asked. “You married?”

The man laughed. “Nah! Still single. I don’t go for girls.”

“How old are you?” Ernesto asked.

“Twenty-eight. I look older, right?”

“I don’t know,” the boy answered. “I’m sixteen. Nearly seventeen—in less than a month.”

“You don’t want to tell me what you do with the ten crowns you’ve got left,” the man said.

“You’re pretty nosy.” Ernesto laughed. “It spends real fast. Some on food, some on the theater. I go to shows almost every Sunday afternoon. I like tragedies best. You ever go to the theater?”

“What would I be doing in a theater? I’m a dumb bastard! Really dumb. I can hardly read or write my own name.”

Ernesto, who like all of the world’s youngsters (and not only youngsters) was more concerned with himself than with others, went on. “I really love it,” he said. “Sunday I saw The Robbers by Schiller. It was great.”

“Made you laugh?” the man asked distractedly.

“Cry! I was so upset when I got home, my mother said that she’ll never let me go to the theater again. It’s throwing out money, she says, if I always come home feeling miserable.”

“And you don’t have a father?” the man asked. “How do you know?”

“Well, you only talk about your mother.” The man sounded almost apologetic.

“I never saw my father,” Ernesto said.

“He’s dead?” The man whispered the question.

“No, he and my mother are legally separated. They separated six months before I was born.”

“Why?”

“I don’t know. They didn’t get along. That’s why I’ve never seen him. He lives in another city. I think he’s not even allowed to come back to Trieste. But it doesn’t matter to me if I see him or not. For all I care, he can stay wherever he is.”

“So you live alone with your mother?”

“My mother and a really old aunt. She’s the one with the money, and she hangs on to it. And I’ve got an uncle, he’s my legal guardian. But he’s married and doesn’t live with us. He only comes for dinner Sundays. And as far as I’m concerned, that’s too often. He’s crazy.”

“Crazy?”

“Totally nuts! A few days ago he tried to smack me as if I were a ten-year-old kid.” (Saying this, Ernesto skimmed the back of his hand along his cheek, making it clear that the threat had actually been carried out, though he was too ashamed to admit it.)

“For what?”

“For nothing. We were talking politics after lunch. I’m for the Socialists. You?”

“I told you, I’m dumb. I don’t get mixed up with politics. But why’s it so important for you to be for the Socialists?”

“What do you mean, why?”

“Because kids like you, they mostly take the boss’s side.”

“Well, I don’t. I can’t stand it when one man profits off another man’s work.”

“You said that to your uncle?”

“Yeah, and a lot more. He may be crazy, but he’s not really mean. After he hit me, he gave me a florin. Three years now, he’s been giving me a florin every week. This Sunday, he gave me two instead of one. Maybe he felt sorry. Like I said, he’s more crazy than mean.”

“Looks like it could be a good deal arguing with him every week.” The man laughed.

“I don’t like arguing. Not that I give a hoot about him, but on account of my mother. It always upsets her. He’s her brother and she really loves him.”

“She loves you, too—more than you think. How could she live with you and not love you?”

“Why are you telling me stuff like that?”

The man put his hand on the boy’s, which lay palm down on the sack. He looked nervous. “It’s really too bad,” he said, surprised and pleased that the boy hadn’t withdrawn his own.

“What’s too bad?”

“What I said before. That we can’t be friends, and go walking together.”

“Because of the difference in our ages?”

“Not that.”

“Because you’re not dressed well enough? I already told you, things like that don’t make a bit of difference to me. So. . . .”

The man was silent for a long time. He seemed to be uncertain of himself, as though he wanted to say something and yet not say it. Ernesto felt the hand resting on his own trembling. Then the man stared directly into the boy’s eyes, and as though taking a desperate risk, suddenly blurted in a strange voice, “Do you know what it means for a boy like you to be friends with a man like me? Because if you don’t know yet, I’m not going to be the one to tell you.” He was silent again for a moment. Then realizing that the boy was blushing and had lowered his head, but had not withdrawn his hand, he added almost belligerently, “Do you know?”

Ernesto withdrew his now damp and sweaty hand from the grasp, which had become tighter, and placed it timidly on the man’s leg. He moved it slowly up his leg until, as though by accident, it brushed lightly against his genitals. Then he raised his head, and smiling brilliantly, stared boldly into the man’s face.

The man was consternated. His saliva dried in his mouth, his heart beat so quickly that he felt sick. All he could manage to say was “You understood?” which seemed more addressed to himself than to the boy.

There was a long silence that Ernesto was the first to break. “I understood,” he said, “but where?”

“What do you mean, where?” the man answered as though in a fog. Ernesto appeared more at ease than he.

“To do that stuff that you shouldn’t be doing, don’t we have to be alone?” he asked.

“Yeah,” the man replied.

“So where do you want us to be alone?” whispered Ernesto, though his daring had begun to fade.

“Tonight, out in the country. I know a place.”

“I can’t,” said the boy.

“Why, you go to bed early?”

“I wish! I’m practically asleep on my feet by the time I get home, but I’ve got to go to night school.”

“You can’t skip once?”

“I can’t, my mother walks me there.”

“She’s afraid you won’t go?”

“Not that. She knows I don’t lie to her. It’s an excuse for her to get out and get some exercise. She wants me to take stenography and German. She’s always saying you can’t go far in the world if you don’t know German. Anyway, I’d be a little scared to be out in the country.”

“Scared of me?”

“No, not you.”

“Then what? My clothes? If you’d be ashamed I could wear my Sunday stuff.”

“Someone could come by and see us.”

“No way in the place I know.”

“Well, I’d be scared anyway. Why not here in the warehouse?”

“There’s always people around. It won’t work,” he said (though he knew that Ernesto had keys to the warehouse). “If the two of us came out of here together after closing, it would look real suspicious. Worse, the boss lives right across the street. And you know that wife of his is worse than him. She’s always looking out the window.”

“Can’t we fake an excuse? Make believe we forgot something? When I’ve got a lot of work to do, I come back in at two, right after lunch. I don’t wait for the boss to come in at three. That’s why he gave me the key. Sometimes I’m alone for more than an hour. And you can always say—Hey, here comes the cart!”

First the heads, then the bodies of two sturdy draft horses appeared in the open doorway. The cart followed, then the carter standing up with the reins and whip in his hands. But even before the horses obeyed his order to stop, a large, heavy man who was to help with the unloading leaped down from the sacks upon which he had been seated cross-legged like a Turk and called out drunkenly to Ernesto’s friend.

“We’ll talk later,” the man said hurriedly and gruffly. Replacing the kerchief he had removed from his head while talking to Ernesto, he headed toward the exhausting task awaiting him. His legs trembled slightly as he walked.

* * * *

After the two men had unloaded the sacks (not without the fat man’s curses and insults), and after Ernesto had completed the work of listing and marking every one of them, Cesco (the fat one), who with all his beggary and bitching must have drunk more than usual that day, started a furious argument with the boss. Ernesto’s friend, however, wasn’t in the mood to argue with anyone. There was only one thing he wanted to do: get to a fry house, gulp down everything they put on his plate, then go home, get into bed, and think. What had happened, or, rather, what was going to happen with Ernesto, was something he’d been dreaming of for months (from the first moment he’d seen him) and he was (if one can ever make such a claim) happy. But his happiness was not untinged by fear—that the boy might have regrets beforehand, feel insulted afterward, or be dumb enough to go around talking about it. But he always accepted whatever payment the boss offered without batting an eye when Ernesto had come looking for him in the piazza. In fact, to his mind, that little bit of money had become much more, because it was Ernesto who was relaying (not setting) the amount. But the fat man didn’t have any such reason not to gripe about money. Moreover he was drunk. The boss, a Hungarian Jew—much enamored of Germany, where he said he had studied and lived for a number of years—was defending himself in dreadful Italian, which gave away his foreign birth. It was an Italian that didn’t merely offend Ernesto, who in addition to being a Socialist was staunchly pro-Italian; it downright pained him. As a child he had read biographies of Garibaldi and of Victor Emmanuel II, the only books in his home, forgotten there by his uncle. What irritated Ernesto most was the word “Germany,” which the boss mispronounced as “Chermany” and which he used frequently (in fact, as often as possible) in order to praise the (unique) virtues of its people. However, Cesco’s violent threats, which the man, as co-worker, was obligated to support, finally prevailed over the boss’s miserliness, which I can’t say had violated any law (there were no laws in those days to protect workers, much less day laborers), although it did violate the accepted practices of the piazza. Grudgingly, he agreed to an increase. That day and from then on, instead of being paid three florins, the two men would be paid four florins to be divided equally between them. It was the amount Ernesto’s friend had wanted, and he immediately turned to leave when the boss called him back to tell him that he needed him to work the next day. He hired him for the entire afternoon. In fact, because it wasn’t possible to deliver the sacks to their destination before three o’clock and many were leaking and required repair, he told him to come in an hour before opening time. He would pay him, he added (though through clenched teeth), for the extra time. Then the very distrustful Signor Wilder, who never assigned a laborer to work in the warehouse without Ernesto’s supervision, turned to the boy to tell him that he too would have to be at work earlier the following day. It was fate speaking (in Signor Wilder’s voice) in a way that was as unexpected as it was peremptory. The man and boy turned away immediately, not daring to look at each other. But something flashed in the man’s eyes and one could see him swallow softly. He left quickly, barely saying goodbye. The boy turned back to his correspondence. But his thoughts too were elsewhere.

* * * *

“We’re alone today,” the man said, when he realized that Ernesto wasn’t going to say anything. He had taken the needle and thread he used for his work out of a bag he always had with him, but rather than concentrating on his work, he’d been awaiting encouragement from the boy—some word about their conversation of the previous day. However, as we noted, Ernesto had remained silent. He was standing nearby (perhaps closer than usual) with his head lowered, twisting the tag attached to the top of a sack. He twisted it so tightly that it broke off and ended up in his hands, whereupon he tore it into tiny pieces and tossed them aside.

“Alone,” he said, finally. “Alone for an hour.”

“There’s a lot of things you can do in an hour,” the man said urgently.

“And what do you want to do?”

“Don’t you remember what we were talking about yesterday? That you almost promised to do. Don’t you know what I’d like to do with you?”

“Yeah, put it up my ass,” Ernesto replied with quiet innocence. The man was somewhat shocked by the crude expression which, more than anything else, surprised him coming from a boy like Ernesto. Shocked, and even frightened. He was sure that the lousy kid, already regretting his halfhearted consent, was taunting him. Worse, that he’d told someone about it or, beyond the worst, that he’d told his mother.

But that wasn’t the case. With that brief, precise utterance, the boy unwittingly revealed what many years later, after many experiences and much suffering, would become his “style”; his going to the heart of things; to the red-hot center of life, overriding resistance and inhibitions, foregoing circumlocutions and useless word twistings. He dealt with matters considered coarse, vulgar (even forbidden) and those considered “exalted” just as Nature does—placing them all on the same level. Of course, he wasn’t thinking of any of that now. He had blurted the sentence (which practically had a laborer blushing) because the circumstances warranted it. He wanted to please his friend, to serve his pleasure, and to experience a new sensation, wanted it precisely for its novelty and strangeness. At the same time, he feared it might be painful. That’s what was troubling him at the moment.

“Is it really that good?” he asked.

“The best in the whole world.”

“For you maybe, but for me. . . .”

“For you, too. Didn’t you ever do it with a man?”

“Me? Never! Did you with other boys?”

“Lots of them. But no one as good-looking as you.” He reached out to touch the boy’s cheek, but Ernesto turned his face away, escaping the caress.

“And what did they say?”

“They didn’t say anything. They were happy. Some of them even asked me for it.”

Ernesto looked down at the part of the man’s body that was visibly excited.

“Let me see it,” he said.

“Sure,” said the man. But as he was preparing to satisfy both Ernesto and himself, the boy stopped him.

“I’d like to take it out. Can I?”

“Absolutely.”

Ernesto would have liked to act out this whim on his own, but his objective was so enveloped in the folds of the man’s shirt, that the man had to help him.

“It’s big,” he said, both frightened and amused. “It’s twice the size of mine.”

“That’s because you’re young. Wait until you’re as old as me. Then—” The boy had just put out his hand when the man stopped him. “No, not with your hand,” he said, “or you’ll make me come.”

“Isn’t that what you want?”

“Yeah, but not with your hand.”

“Oh.” Ernesto withdrew his hand, as if from a forbidden thing.

The man was slowly moving closer to him. “I’m scared,” Ernesto said.

“Of what? Don’t you know I love you?”

“I believe you, otherwise. . . . But I’m afraid that you’ll hurt me just the same.”

“Me hurt you?” The man smiled. “I know how to take care of a boy who’s doing it for the first time. You especially.”

“You’re not going to put the whole thing in?”

“You crazy?” The man smiled. “It’s gonna be a nothing, just the tip.”

“Sure, you say that now. But later when you get carried away. . . .”

“You’re so adorable,” the man thought, and vowed to himself not to hurt the boy in the slightest, even at the price of his own pleasure. “I’d cut it off myself, rather than hurt you,” he said, and tried once again to kiss Ernesto, who as before escaped the embrace.

“So bend over now,” he pleaded. “If you don’t, our time will be up and we won’t have gotten anything done.”

“So you want to get something done?” Ernesto laughed.

“You want to, too. Aren’t we here for that? As long as,” he added in a hurried whisper, “you’re not sorry afterward.”

“I already told you I won’t be. But how about a deal?”

“What kind of deal?” asked the man, who had no idea what Ernesto could want. If he weren’t a poor man and the boy weren’t (as least, to his mind) wealthy, he would have feared he wanted money, which would have ruined everything.

“You have to swear that if I stay stop, you’ll stop. And right then, at that moment.”

“I’m sure you won’t have to say stop. But I promise just the same.”

“It’s not enough to promise. You have to swear!”

The man laughed. “On what do you want me to swear?”

“Don’t laugh. Then you’ve got to give me your word of honor.” And the boy extended his hand as if to seal a contract.

The man shook it.

“No matter when, and immediately?”

“No matter when, and immediately,” the man repeated.

Ernesto looked calmer. “Then,” he hesitated, “okay, if you really want to. . . .”

“God bless you. And now take off your jacket”—the man had already removed his—“then drop your pants.”

“You too,” said Ernesto.

“Sure.” And as the man began to do so, Ernesto had another idea. “You take mine off,” he said, “and I’ll take yours off. Okay?”

The man agreed.

“And now,” asked Ernesto, “where do you want me to go?”

“There,” the man said, and pointed to a low pile of sacks, at the top of which was the one whose label Ernesto, in his consternation, had ripped off and torn to pieces. They were medium-size sacks containing flour marked with a double zero, the whitest and finest in commercial use, and so expensive that few bakers purchased them. The sacks were piled to almost Ernesto’s height under an arch in an out-of-the-way section of the warehouse where no eyes, except perhaps God’s, could see them.

Ernesto did as his friend asked. He bent his upper body forward over the sacks. The man leaned forward over him and slowly lifted the shirt, which the boy, perhaps with unconscious coquetry, more likely because of the confusion of emotions overwhelming him, had forgotten to remove. (It was the last protection, the last curtain between himself and the irrevocable.) Both the man and the boy were trembling.

The man caressed the part of Ernesto’s body that he had slowly exposed, but just briefly, fearing the boy’s impatience. Similarly, he withheld the words of tenderness, admiration, and gratitude that were rising from his heart, words that Ernesto would have difficulty understanding, that he might not even hear. Instead, he said something vulgar, almost a response to the boy’s earlier remark that had caused him to blush.

Ernesto didn’t answer. Filled with curiosity and fear, he couldn’t have spoken even if he’d wanted to. And then, what was there to say? He heard the man asking him to change his position a bit, and obeyed the request, as if it were an order. “I’m a goner,” he suddenly thought, yet without regret or desire to turn back. Then he felt a strange, indescribable sensation of heat (not at first without pleasure) as the man found and established contact. Neither of them uttered a word, except for an “Angel” which escaped the man just before coming, and a precautionary “Ow” emitted by the boy when he felt the man pressing a bit too hard. But the man kept his promise. He didn’t (or tried not to) hurt him. For the most part, it all went more easily and lasted less time than Ernesto had imagined. When the man had withdrawn, he asked the boy to remain still for another moment. “What else can he want to do with me,” Ernesto wondered, but felt relieved when he saw the man take a handkerchief from his pocket. All he wanted to do (either as a courtesy, or to remove any traces) was to wipe him clean. At that moment Ernesto felt like a child—a confused, disoriented child.

“You were good, good as gold,” said the man when he and the boy had dressed again and dusted the flour off themselves.

Though Ernesto frowned, he enjoyed the praise. “Was it good for you?” he asked.

“I was in paradise. But you liked it, too, say so.”

“Not that much! A little at the beginning, then it began to hurt. I even shouted.”

“You shouted?”

“Didn’t you hear when I said ‘Ow’? And why did you call me an angel?”

“What else should I call you?”

“Angels don’t do that kind of thing,” Ernesto replied sternly. “They don’t even have bodies.”

“We came at the same time,” the man said.

“How do you know?”

“I felt you coming, you can always feel that kind of thing. Anyway, look over there.”

“Where?” Ernesto asked, frightened.

The man pointed to a stain on the double-zero flour sack, the very one whose tag Ernesto had ripped off, and over which he had bent.

Ernesto looked, and felt sickened.

“It shows,” he said. “We’ll have to turn it over. Want to do it now?”

“Who’s gonna know what it is?” the man said. “But if you really want me to, I’ll do it later.”

There was a silence, a fairly long uncomfortable silence. The man seemed to be thoughtful, almost worried.

“What are you thinking?” Ernesto asked, disturbed.

“That I’ve got to say something I don’t really want to say. Maybe I should have said it before. You won’t tell anyone what we’ve done?”

“Who do you think I’d tell? I’m not that dumb. I know what you can and what you can’t tell.”

The man seemed relieved. But the worst was still unsaid.

“It’s a risky business, you know. People don’t understand, and you can—you can even go to jail.”

“I know that, too,” Ernesto replied triumphantly. “I read in the paper about two guys like us, a man and kid, they got caught in a bathhouse. The headline was ‘Aftermath of a Swim.’ The kid got four months, the man got six. Wotten!” he concluded, slurring the r for some unknown reason.

“And when that happens,” the man blurted, laying it on thicker, “there’s nothing to do but drown yourself for the shame.” Then he felt sorry for tormenting the boy.

“Don’t worry,” the boy reassured him. “As long as we don’t get caught like those two idiots. It was the attendant—he thought they’d left, but when he opened the door he found them in the act. Instead of keeping his mouth shut, the dimwit screamed like hell. You didn’t notice, but I made damn sure you bolted the door.”

Ernesto smiled, but the man remained thoughtful, almost sad. “Anyway,” said Ernesto, “it’s something else that’s bothering me.”

“What?” the man asked anxiously.

“How am I going to look at my mother tonight?”

“Like you do every night,” the man answered, hiding his agitation. “If she doesn’t know anything, it’s as if nothing happened.”

“But I know it did,” Ernesto replied seriously. “And I have to go to school. On the way she’ll ask me about everything that happened during the day. My mother’s real nosy—she always wants to know everything.”

“Women are nosy,” the man replied. “But you can’t say a word, and I mean not one word about what happened between us. Maybe she’d forgive you, but never me. . . . And don’t think you’re the only kid who did what you did today. But I asked you to, for love, because I really love you. You’re not the same kind of boy like the ones you take on once and then dump. I think of you like you’re an angel. That’s another reason I don’t want anything bad to happen to you.”

“Okay,” Ernesto replied. Then after a brief silence, he asked, “How many boys do you think have done what I did today?”

“What do you mean how many boys?”

“Well, take a hundred, how many of them would’ve done it?”

“How should I know?” The man laughed mirthlessly. “All I can tell you is that I never asked a kid who said no.”

It was the truth. What he didn’t say was that guided by an almost infallible intuition, he asked only those boys who in their adolescence manifested an inclination in that direction. (Later, almost all of them would change. They would forget or try to forget everything about it.) Many also (but the man wouldn’t have told Ernesto this, at least not then) asked for money. Their price wasn’t high (just a florin). But day laborers didn’t always have a florin to indulge their pleasures. If he were rich, he would have liked to give Ernesto an elegant gift (though not of money). He wanted to give him something for the pleasure he had felt, and because he knew that it thrilled boys to get presents. (Nothing beguiled them more.) But even if he had the money, he couldn’t do it. The boy couldn’t have resisted showing it off to his mother or his friends. (The man was sure, who knows why, that Ernesto had many friends, though in reality, he had few or none at that time.) Even if Ernesto wanted to, he wouldn’t have been able to hide the gift. Because what the man wanted to buy him was a gold tiepin, perhaps even one that was set, as was fashionable then, with a small gemstone. But it was useless to even think of it.

Meanwhile Ernesto was pacing up and down the warehouse. He seemed to be—he was agitated. The man, having taken out his needle and thread, began to work.

“I’ve got to get to work,” he said. “Otherwise, who knows what the boss’ll say when he gets back and nothing’s done.”

Ernesto sat down next to him and watched as he worked. But he didn’t remain seated very long. In a few minutes he was up and pacing the warehouse again.

“What’s wrong?” the man asked.

“I’m burning.” Ernesto sounded apologetic, as if it were his fault.

“It’s nothing,” the man reassured him. “It’ll go away in an hour, maybe less.”

“You think so?”

“Absolutely. As easy as I did it, I don’t know why you hurt.” “Can I ask you a question?”

“Sure.”

“Is it true that when you’re called up by the army, they examine you there, and they turn down anyone who—”

The man burst out laughing, and once again his laugh had a forced quality. But then he reassured the boy on this issue, too. He himself had been conscripted eight years earlier, and no one thought of examining him where Ernesto feared. Not him, nor anyone else. “How the hell,” he asked, “did you get such a dumb idea in your head?”

“It didn’t just come into my head,” he replied, somewhat irked. (He felt that the man had thought him foolish.) “A friend told me. About a year ago.”

The man recalled that he, too, had once heard something like that and had believed it as completely as Ernesto had. He’d thought that Ernesto was too educated to have fallen for such an improbable tale. Now, however, he wanted to reassure him. A kind of intuition told him that, for the moment at least, the boy was having regrets, and that all his notions, his complaints, and in a certain sense even the burning sensation were more than anything else the effects of the regret, which he, in his unremitting egotism, hoped would soon pass. In addition to the love he felt for the boy (rare in a man of his disposition), with Ernesto he hadn’t experienced any of the revulsion that overcame him with other boys, from whom he would distance himself—flee—as soon as he’d had them. He felt as if he could be with Ernesto forever. And though he’d had to frighten him a little, he was unhappy to see him so worried and distracted now.

“You still thinking about your mother?” he asked.

“Not now.”

“So what are you thinking about?”

“Nothing.”

The man resumed his work. Then suddenly he stopped, and sounding almost maternal, asked, “You still hurt?”

“Yeah, still,” the boy answered, for the first time sounding reproachful.

“Next time,” the man risked, “I’ll bring something so you won’t feel anything bad during or after.”

“What kind of thing?” Ernesto was immediately curious. “Something you get in a pharmacy.”

“You get stuff in a pharmacy for doing this? But then—”

“No, not for doing this,” the man replied. “It’s for people who’ve got problems kind of like that. It’s a cone you put up there, it melts in five minutes because your body’s warm. Afterward, kids don’t feel the kind of pain that’s bothering you now.”

“So what’s this cone made of?”

“Cocoa butter,” the man replied, never anticipating the effect his explanation would have on Ernesto.

“Cocoa butter, cocoa butter,” Ernesto repeated over and over again, then burst into laughter—laughter so intense that he had to sit down. Tears began streaming from his eyes. He looked as if he would never be able to stop himself.

“Cocoa butter up your ass! All the things you know!” the boy said and went on laughing with such delight that its bright, youthful sound cleansed the room of the oppressive air that had filled it. The man was now laughing, too, as though happy and calmed by the youthful joy exhibited by the boy, who didn’t quiet down but continued repeating the components of the medication and the place to which it was applied. The man felt like hugging and kissing him, but didn’t dare. Experience had taught him that young boys didn’t like being kissed. They knew nothing about giving or getting kisses. He was looking gratefully and lovingly at Ernesto when they heard an almost angry banging at the door. It was the boss, who had been knocking for a few moments and was annoyed not to have been let in. He was sure that Ernesto and the worker had forgotten, or had disobeyed his order of the previous night and hadn’t shown up. Laughing too hard to get up and open the door, Ernesto handed the key to the man who rushed over to let the boss in. He entered, grim-faced, and looked about suspiciously. Addressing Ernesto in his usual bad Italian, he asked what was so funny. But Ernesto (who, when he couldn’t tell the truth, would rather not say anything) didn’t answer. The boss shrugged his shoulders and, though not angry, stared at his young employee. He liked the boy, though he’d never let him know it, fearing he’d lose face in doing so. Muttering “verfluchter Kerl ” (damn kid), he started towards his office, then looked at his watch and ordered Ernesto to be there in five minutes. He had to give him and the man the papers required for consigning and shipping the goods.

* * * *

“Aren’t you going to turn the sack over?” asked Ernesto, who had finally calmed down and recalled his earlier fears. “Aren’t you going to do it for me?”

“Right away,” the man answered, “but believe me, it’s not necessary. It’s just a little extra work, but for you”—he looked lovingly at the boy—“if it’ll make you feel better, I’m happy to do it.”

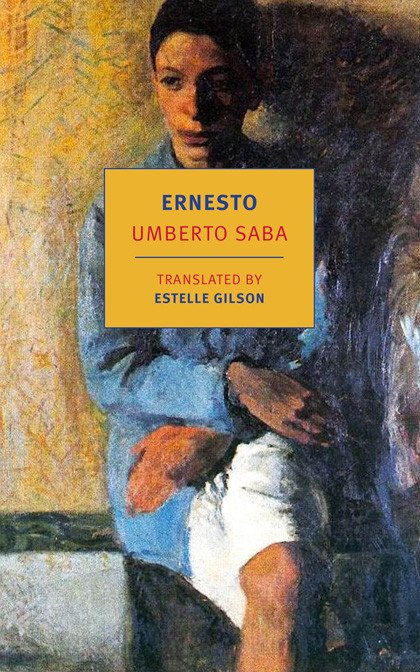

From ERNESTO. Used with permission of New York Review of Books. Copyright © 1975 by Umberto Saba.