Enki Bilal on the Frightening Speed of the Digital Revolution and Finding Meaning in Humanism

Ayşegül Sert Visits the Legends of Today Creator's Parisian Studio

Featured photo by Hannah Assouline.

It is a sunny weekday morning and one of France’s most influential comics authors is already busy. As I stand at the door of Enki Bilal’s Parisian studio, he speaks on his cell phone, gesturing with his hands to come in. He is wearing sneakers, a dark blue shirt, and jeans. Newspapers and magazines are spread around, while tables are filled with brushes, pencils, and papers. He has separate tables for where he writes and where he draws. There is a sofa where he reads and large windows throughout. In this artistic chaos, everything seems to have its precise place. Bilal has the capacity to daydream anywhere and anytime: in Corsica, at his other home studio, on a national book tour, exhibiting his work at the Louvre and at the Venice Biennale, in San Francisco or in New York.

His comics, which he calls “fables,” offer a new way of describing dystopia and metamorphosis, of imagining the city, the cosmos, and the collision of the intimate and the geopolitical… all in the form of a sci-fi epic. His three-volume book, Legends of Today, was published in English by Titan Comics this year in the midst of the pandemic. Today, Bilal is at work on another series, Bug, part two of five installments already published in France, in which he describes a near future when a digital bug interrupts life worldwide.

Born in Belgrade in 1951, his father is Bosnian, and his mother is Czech. His last name, Bilal, is of Ottoman origin, and Enki is short for Enes. This October, the only son of a father who was Marshal Tito’s tailor celebrates his 70th birthday. Charismatic, clever, emotionally reserved, he is a boundary breaker with a curious mind. The bells of St. Eustache ring in the background Bilal tells me about overcoming the trials of a childhood in the shadow of World War II, and about becoming the artist many regard as the most intellectual of the genre. “Whatever I do, I can’t seem to get away from my obsessions,” he tells me as I press record on our conversation.

*

Ayşegül Sert: So here is where the literary magic happens…

Enki Bilal: I have had this loft since 1994. At first it was just this main area [he points to the first half of the space] and then one day, the neighbor next door told me: “You must start to feel the need for more space,” and he asked me if I wanted to see his flat. The timing was right, I was thinking of leaving, and I used to stare at our common wall wanting badly to dismantle it. And in 2003 I got to do it.

AS: You have come a long way. When you were a child in Belgrade your father left for Paris, you were left behind with your mother and sister struggling to survive.

EB: With the exception of our schoolbooks, there wasn’t much else around. I found ways to exchange comics I read with others. I used to sneak in movie theaters. I found refuge in dreaming of the vast spaces I saw on the big screen.

AS: When your father left his desire was to reach the USA. France was to be a transit point. He never got to his final destination, but decades later his son did, as your books are translated in English and you have had exhibitions on both American coasts.

EB: In a symbolic sense, I made the American dream he never got to realize, that’s true. In his old age, my father traveled to Chicago, he had a cousin there and stayed for a couple of weeks, and at least he got to see the country he had fantasized about for so long. Neither he nor I physically settled in America, but my books, which are an extension of me, made the journey. I love New York, I think it is an incredible city. I stayed in Los Angeles for over two months for a book project and loved it. When I think of the US I think of the Grand Canyon, I think of Death Valley—those landscapes carry a grand force. Americans succeeded in finding the ultimate weapon of mass destruction: Hollywood! It invaded the world. I think that Europeans should have done the same, but they didn’t rise to the occasion. Had they done it, we would have truly had a single strong European culture, which we desperately need.

AS: Europe seems to have opted to define itself as an economic project.

EB: Arts are regressing and taking a backseat today and that frightens me. One of the factors contributing to this is the digital revolution. The revolution that came with Gutenberg and printing was incredible, though it spread throughout the world in a gradual manner. The digital revolution was almost instantaneous, and in order to keep up with it, our lives turned frantic. If you don’t keep up with it, you feel lost and excluded. What frightens me is that in this context, a form of transmission to younger generations is getting lost, and there is no turning back.

I found refuge in dreaming of the vast spaces I saw on the big screen.

Youth today understands fast, acts fast, communicates fast, and as a result, only stays on the surface and superfluous. Reflection demands concentration, it demands time, it demands slowing down. From obsessing about wanting to grow a financial benefit from everything, without taking the time to pause, reflect, and discuss, the lack of transmission between the 20th and 21st century was unpreventable. On top of it, the 21st century began with a catastrophe that took the planet by a state of shock, that is the 9/11 attacks. There is something terrible here: The world watched the images of the World Trade Center as they were happening in real-time. All this tells of a fast mutation, and this transformation of society is worrying, particularly for the inconsequential standing of culture.

AS: I find it puzzling that someone like you who follows national and international politics close-up does not use his right to vote during elections. How come?

EB: I always voted for the Left and could never get myself to vote for a Right-wing party. There is no danger that a dictatorship could happen in France. The last time I voted was about two decades ago, aiming to block Jean-Marie Le Pen [far-right] from taking the lead. I voted that once and that was enough. If I am not convinced by a candidate, I am not going to vote just to say I voted. I am not ashamed not to vote, it is a completely assumed act. I am not a dupe; I saw early on that in politics promises are made and they are rarely kept.

I was surprised by Donald Trump’s election in 2016, like many I did not expect it. He is such an atypical personality. He accumulated many foolish acts, so much so that one couldn’t help but think it must be a Surrealist theater play—his take on Covid-19, his dangerous “pas de deux” with Kim Jong-un of North Korea, his misogyny… I have the feeling that the pandemic has shown us that something in Western societies has come to its end. I am confident of young generations; they are rebooting the system, calling for urgent environmental action. We are shifting gears. Today’s ecologists, in France at least, are politicians and ideologues; they compromise. In truth, ecology should be held above politics, it’s a philosophy, it’s a way of seeing life and protecting it; ecology deserves a form of purity and humanism, what politicians often lack.

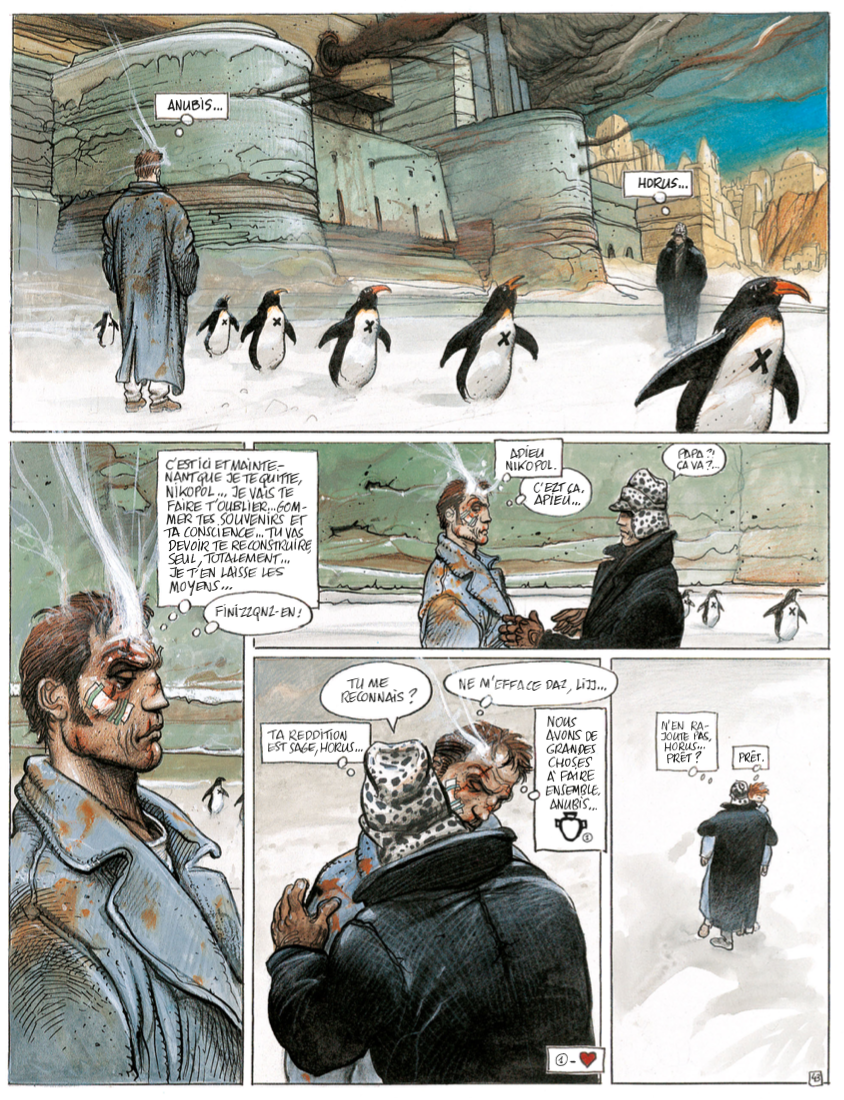

A page from Integrale Nikopol.

A page from Integrale Nikopol.

AS: How do you feel about the fact that your book, Legends of Today, was published a few months ago in the US though the book saw light in France over two decades ago?

EB: I have a hard time looking at what I did in the past. It’s hard for me to look back at this book. I accept it, it’s a part of my life. I don’t know a single actor who likes to watch the movies he starred in; you could say I am the same way about my books. I don’t re-read my work and it’s in order to keep a sense of freedom. I don’t fancy wandering in the past, I move on, in my books and in my life.

AS: Is that why you think cancel culture can be dangerous?

EB: I am quite worried about it. It sanitizes everything and from a narrow standing point in the present time it attempts to reorganize things and I think it can backfire.

AS: You are a fan of European literature.

EB: Correct, though lately I can’t get myself to read novels. I mostly read essays now. When I begin reading a novel my imagination takes control and a random line carries me on to other realms and I am no longer in the book but in my mind creating. Sometimes I open a novel, read a couple of pages, and then I stay immobile and people call me out teasing: “Enki, you’ve been on the same page for half an hour!” In truth, I am no longer on that page, I disconnected a while back…

AS: Do you think that an author can or should be apolitical?

EB: My sense of engagement goes through nuance, a look at the big picture upon taking a step back. I look at the world from an artistic point of view, like an observer, which allows me to adopt a form of lucidity on how politics function, which perhaps comes from my origins. I was born in 1951 when politics and ideology were omnipresent. There is one thing I abide by fully and it is humanism, which is a hard sell in politics.

AS: Where is “home”?

EB: Each time I got back to Belgrade from Paris, I was moved to be reunited with the city. Belgrade will remain my city. In 2019, as I was accompanying French President Emmanuel Macron to Belgrade on a state visit, he unfolded a piece of paper and told me: “Now you are going to coach me,” and he read me his speech in Serbo-Croatian. Such visits are usually to discuss trade or defense partnerships, but it was important for him to include the cultural issue. My mission, so to speak, was to meet with young artists there, and to see how the two countries could collaborate. Once we arrived at the square for his speech, all of a sudden all my childhood memories resurfaced: We were standing where I used to play as a kid and right across the park was the house where I was raised.

AS: In France, although one out of five books sold are comic books, the genre is looked down on, not considered a high-form of literature. What’s your take on this?

There is one thing I abide by fully and it is Humanism, which is a hard sell in politics.

EB: For me, it is literature and contemporary art. I’ve a difficult time understanding how Roy Lichtenstein—who reproduced comics boxes—is renowned and respected in the art world while comic books are shunned. I regard comics as a living art, it’s crucial to make them evolve. In France, after long and hard-fought battles, comic books are recognized as a part of culture, one we can leave up in the open on our library shelves, that is a huge win. The battle is not over. The more culture will be fragile, the more the divisions will be apparent and the more we will need books. Some so-called high-art circles will continue to consider comic books as a low-artform, and those people may deny it but I can say that comics help advance the world from a xenophobic to a more humanist one.

AS: When you begin working on a book, what comes first: The plot or a drawing?

EB: In my early years, I did what I was told, which was to write the whole story first and then to draw. It did not satisfy me. I needed to feel free in the process, to let inspiration guide me instead of setting everything up beforehand. So I switched. Today, for instance, I am working on page ten of my new book, I know what will come on pages 11 through 14, but after that I have no clue, I move forward as ideas come. I draw on one corner of my studio [he points to the desk and computer opposite where we sit] and then I go off to write on the other [he points to the other side where there is another computer and desk]. Sometimes the text says more and sometimes the drawing. This, for me, is freedom.

AS: You learned the French language upon your arrival in Paris around the age of nine. Today, it is the language in which you create, write, and live. As the country adopted you, you adopted its language.

EB: I got assimilated into French society. Assimilation is sometimes regarded as suspicious, as if it means to betray one’s origins, which is absolutely wrong. Mine happened through and thanks to language. When we love a language, we want to master it. My roots and my childhood souvenirs before the French language are still vivid and a part of me. On the contrary, this newfound language allowed me to better comprehend and name who I am. At first of course it was frightening both for myself and my sister; we wondered how we were to learn it. And when we got to school it was as if the French language whispered to us: “I will be kind to you don’t worry.” Soon enough, we were seduced by its grammar, musicality, and rich vocabulary. There is something reassuring in holding a book in your hands, to take a pause from one’s daily life and worries and abandon oneself to a story told through pages and characters, and all that under the banner of a new language!

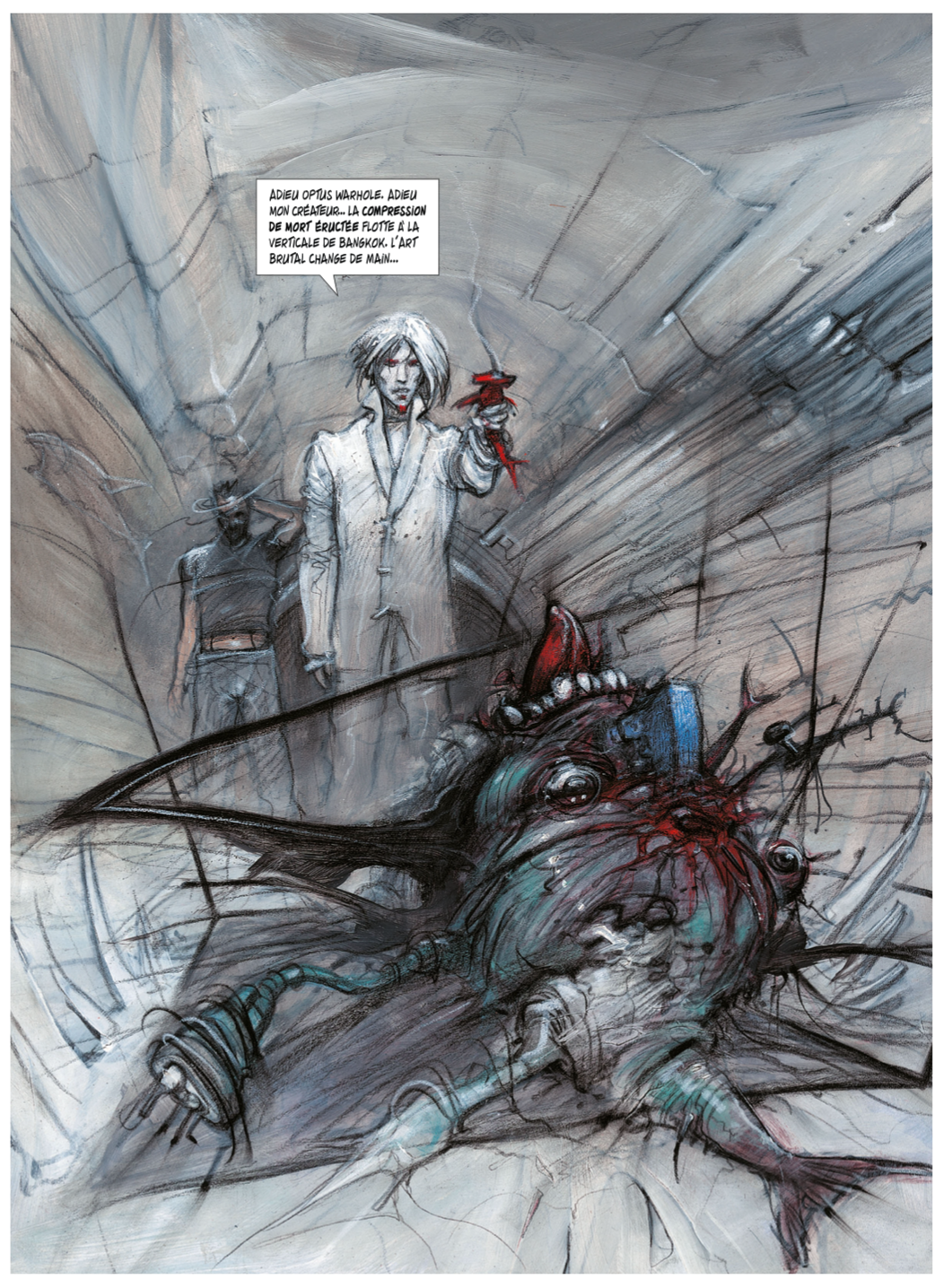

From Rendez-Vous a Paris.

From Rendez-Vous a Paris.

AS: In the 1990s you returned to your hometown, Belgrade, and also to Sarajevo, your father’s hometown. Returns often demand extreme courage and strength…

EB: I still feel an unshakable feeling of injustice and atrocity in my body when I think of the bombardment of Sarajevo. When I was a child, we used to visit my father’s family, and I remember the sense of apprehension that I had because the city we lived in—Belgrade—and this other city—Sarajevo—seemed so different. Sarajevo was an unbelievable mix of faces, histories, and religions. With the war, it all turned into clashes of religion and nationalism. This war haunted me a great deal. Europeans and Americans see things from an oversimplifying prism of “good” and “evil.” Reality is more complex, and their lack of nuance frustrated me.

AS: Any predictions for the French presidential elections to be held in less than 8 months?

EB: Emmanuel Macron wants to stay in a position of force, for now what appears is a possible second round with Macron versus the far-right candidate Marine Le Pen, if that is the case I think—I hope!—Macron will win.

AS: What do the following names evoke for you: Art Spiegelman, Stan Lee, and Jorge Semprún?

EB: Spiegelman did a masterpiece, a universal and immortal work [Maus] on one of the worst instances of denying humanity, and this work will stay on. Lee [Marvel Comics] is all about the force of dream and imagination, and such an indelible voice. Semprún, I knew him personally, he is one of these great authors who were also thinkers and sensitive souls as much with their writings as by their political engagement. These three gave to books a nobility.

AS: What would the 70-year-old Enki Bilal tell his nine-year-old self at the train station platform in Belgrade with his suitcase about to embark for Paris and leave all he has known behind?

EB: That boy did not want to go on that journey so I’d tell him: Close your eyes and let yourself be, it will be a 42-hour train ride but it will be worth it.

AS: Where does this passion for the written word comes from?

EB: Probably from the fact that I really wanted to see my work be printed in books. I was very impressed with the French language, it was an odd feeling, perhaps it happens to anyone who discovers a language later in life, where you are moved not only intellectually but physically when you read a beautifully crafted sentence in a language that is at first foreign to you and soon enough becomes yours.

AS: You despise the genre of autofiction, though isn’t it inevitable that a part of an artist transpires in his/her work?

EB: I am annoyed by the so-called autofiction phenomenon in France. It is extremely pretentious to say: Well, I am going to write a book about myself! You’d better have something extraordinary to tell! Displaying one’s life miseries is not of public utility if you ask me. Of course, one is free to write the book he/she wishes to, especially if it’s poignant. But for me, autofiction is justified if it can reach the universal, if the message goes beyond the Me, Me, Me. I see only a handful of examples who succeed in that. When Salman Rushdie writes it’s spectacular to read and witness the writer’s process. American authors do it best, they have this talent to integrate their own life into the big picture.

What I read in France in this genre is depressing. Maybe it is also that I find imagination to be an extremely important thing to preserve and I am always afraid that the day will come when we will be forbidden to imagine. Books allow the author and the reader to reach a grand freedom. Literature unites us, it ties us to one another, bringing together sensibility and memory. We are all a bit worried about what literature will become in these fast-changing times. I believe there will always be people who will read and write, and literature will survive because it is vital. All this profoundly preoccupies my mind.

Literature unites us, it ties us to one another, bringing together sensibility and memory.

We ought to fight for culture and for literature, this is an essential fight to carry on today; it’s been my life’s work and effort. I notice that young generations read less and it breaks my heart. Though, I must say, that it is interesting that when they read, they do it in a different way than my generation for instance: They read diagonally, they do fast-reading, and I think this rapidity along with the online world accelerates everything including their intelligence and thinking speed. Some people are extremely worried for the young and believe that they are going to hit the wall; I am not so sure, I wait to see. It’s up to the young, it’s their playing field, it’s up to them not to abandon literature along the way.

AS: I know some things are not negotiable in your life, such as reading the news in the morning with your cup of coffee and turning on the music as soon as you step into your studio to work. Some habits die hard, is that it?

EB: Yes, but some disappear, unfortunately. There is no longer the kiosk where I used to buy my morning newspaper. The owner was the first person I used to see, it was a ritual to wake up and go down the street to get the paper, and one day he told me goodbye, and the newsstand became a restaurant of rotisserie. So we adapt. Now, I read the news online. Regarding music, my taste is eclectic, rock is my thing—Pink Floyd, The Stones, Radiohead, The National, which apparently Barack Obama fancies as well. I listen to classical music too, particularly classical sacred music—I know for a person who is not religious, who once was an atheist and is now an agnostic, it’s strange… I live by Church St. Eustache, I love passing by a synagogue, to enter a mosque, and I find Buddhist cult spaces magical. Go figure!

AS: How do you explain your longevity—what makes you go on?

EB: I think there is the chance factor, that’s for sure. There is also the fact that I do different things; even if the core is the same, I try new areas, which allows me to question myself and my work for purely vital reasons, to constantly push myself forward. I changed my drawing technique because I could no longer bear the classical way of doing it. I did films and décor for the ballet, opera, theater, I created installations, I wrote a one-man show…

Looking back—which I rarely do, I am a man of the present—all this was subconsciously in order to preserve my desire to use my imagination in different ways and not be locked in a single category. I believe this gives me a form of sincerity in my artistic endeavor, which is reflected in my books, and readers follow that sincerity. When I did my book Animal’z, some critics said I was pretentious to go off track from my usual style. There will always be people who don’t want the world to change, who are terrified it might. They don’t know what they miss out on! [He laughs]

Translated from French and edited for length.

Aysegul Sert

Born and raised in Istanbul, fluent in four languages, Ayşegül Sert has reported extensively from Turkey, France, and the United States. Her articles are published in The New York Times, Le Figaro, Le Monde, and The New Yorker. An advocate for writers at risk, her work focuses on freedom of speech, gender equality, and human rights. She is a guest commentator on Arte and France Culture on issues related to international politics and culture.