Elmore Leonard was a famous writer, but this isn’t a story about him. This is a story about my friend Elmore Leonard, who wasn’t a famous writer at all. Oh, he was a writer, my friend Elmore Leonard; he just wasn’t a famous one. I don’t know if he was a good one either, because he never wrote anything.

He tried a lot; he tried really hard. He had a fancy typewriter and everything. It was one of those ones that comes in its own suitcase, in case you ever go anyplace.

Not that Elmore ever left his mom’s house. He was too busy waiting for inspiration. He’d just sit there and sit there, staring at the page.

I don’t know what I’m doing wrong, he’d say.

I remember one day, I finally got up the nerve to say that maybe Elmore wasn’t meant to be a writer. I mean, maybe his talents lay in other directions?

But Elmore didn’t want to hear about that.

I just can’t help but feel, Elmore said in a loud voice, that with a name like Elmore Leonard, I’m destined to be a famous writer.

And it was hard to argue with that.

Elmore had a job at one of the factories, and he stayed clean and sober, so it didn’t really seem like that big a deal that he wanted to be Elmore Leonard the famous writer. After work he’d come home and sit at the typewriter for a while, and then I’d come over and we’d drink beer. It was harmless, like how some guys play in bands on weekends, or some people always read the newspaper.

But then, one day, everything changed. One day I went over to Elmore’s house, and he came up to me carrying a book.

Look what I wrote, he said.

I looked at the book. It was an Elmore Leonard book. Rum Punch, I think. Maybe Maximum Bob.

This is an Elmore Leonard book, I said. Exactly, Elmore Leonard said.

After that, Elmore had to go live in the hospital. His mother was very upset.

What’s wrong with him? she kept asking me. He thinks he’s Elmore Leonard, I’d say.

Sometimes I’d go see him, and we’d sit in the visiting room. They wouldn’t let him have any of “his” books. I remember one time he was reading Edgar Allan Poe.

This guy’s crazy, he said.

He asked me if I could sneak him in one of his books, and I promised him that I would try. And I did, but unfortunately I was caught, and then they put me on the Do Not Visit list.

After that, Elmore and I sorta drifted apart. Neither of us were too big on writing letters. I think Elmore might’ve sent me a postcard one time, but I’m not sure, because there was nothing written on it.

For a while, nothing happened; time just passed. I went to work, came home, watched TV. But then one day I saw that Elmore Leonard book sitting there—the one I’d tried to sneak in to him at the hospital.

The book was on the couch, where I’d thrown it that night. I don’t know why, but I picked it up and started to read. I’d never really read a book before then. I mean, unless it was for school or something.

And the thing of it was, the book was really good! It was funny; it made me laugh. It was about these two guys who tried to rob a bank and then one of them got caught and put in jail. But the thing about it I liked was that the characters were good; it really seemed like they were best friends. They had fun, even when they were running from the cops. Except of course for when the one guy was in prison.

So I read the whole book, and then when I was done, I just sat there, staring at the cover. Staring at that name there—my friend’s name on the book. That name that had caused him so much trouble.

And as I was looking at it, a thought came to me. It was a thought that I’d never had before. So I got in the car and drove to Elmore’s mom’s house.

Why’d you name him Elmore Leonard? I said.

And Elmore’s mom looked at me, and then finally she frowned. It was his father’s idea, she said.

She opened the door and ushered me in.

She motioned toward the wall with one hand.

I’d been in Elmore’s living room a million times before, but somehow I guess I’d never seen it. I knew the walls were lined with shelves of old books.

But I’d never noticed they were all Elmore Leonard novels.

His dad sure did love those, Mrs. Leonard said. He used to sit there and read them, and laugh and laugh. That is, of course, until the day he finally left. That was when Elmore was three or four, I guess.

I stood there and stared at those books on the wall. Then something happened: I started to cry. And Mrs. Leonard heard me and turned in surprise.

Well, what’s wrong with you? she said.

The way she said it, it’s hard to describe. It almost sounded like she was mad. Mad at me—like I’d done something wrong.

It’s nothing; I’m sorry, I said.

I excused myself and went on home. I drank a beer and tried to watch TV. But after a while, I turned it o .

I went to bed, but I couldn’t sleep.

I just lay there in the dark, thinking about Elmore, and about those books on the wall. About Elmore’s father sitting there reading them and laughing. And then the silence that must have fell when he was gone.

And then I started thinking about the characters in that book. How they were friends and stood by each other every day. And then I thought of Elmore sitting up there in the hospital.

And I knew I had to get him out of that place.

So that night I went out and put gas in my car. Made sure everything was running ne. I went to the bank and took all my money out.

Then I drove to the hospital and put the ski mask on.

I went in through the roof; it wasn’t really that hard—took a crowbar to a rusted old lock. There was a guard but I hit him with the butt of my dad’s hunting rifle.

Come on Elmore, I whispered. It’s time.

We ran down the stairs and burst out the front doors; we were halfway to the car when the sirens started to whine. We peeled out of the parking lot, past the first cop cars as they came, took the shortcut through the hills to Route 9.

We were screaming down the highway at 110; I remember the needle going all the way o the dial. There were helicopters and searchlights; I don’t know how we got away. There was just this voice in my head saying, Drive, drive.

The sun was rising as we crossed the state line, and I be‐ came of aware of this kind of noise. I looked over and saw that Elmore’s mouth was moving.

Pull over, he was saying. We’re all right!

We stopped by the side of the road and just sat there for a while. My knuckles were still white on the wheel.

Thank you, Elmore said. I can’t believe you did that. No one ever came back for me before.

Oh hell, I said, you would’ve done the same.

But Elmore just shook his head.

Maybe, he said, but I kinda doubt it. Let’s find a gas station, though—I gotta go.

A few miles down the road we pulled into a mini‐mart; I grabbed a case of beer and a couple of Snickers bars. On the way up to the register I noticed Elmore looking strange. He was standing there, staring at the newspapers.

I walked up beside him. He’d gone completely white.

What is it? What’s the matter? I said.

Then I looked over his shoulder and saw that huge headline.

Elmore Leonard the famous writer had died.

Oh, I said.

Then I looked at Elmore.

But it’s okay, though, I said. It isn’t you.

I know, Elmore said. I’m better now, you know. It’s just, he meant a lot to me, is all.

I picked up the newspaper and paid for all the stuff, then we went outside and sat in the car. We drank a few beers and ate the Snickers bars, while Elmore read the obituary aloud.

It was all about the life of the real Elmore Leonard— how he was born in New Orleans and grew up in Detroit. How he went to a Jesuit school and then joined the navy. How he had almost fifty books in print. But the best part came when they talked to his friends, and they told all these stories about his life. From the way they talked, you could tell they really liked him; you could tell Elmore Leonard was all right.

And at the end of the article, it talked about his funeral, which was gonna be the next morning at eleven o’clock.

We could make it, Elmore said. I mean, we’d have to drive fast, but it’s not that far, just Detroit.

But Detroit? I said. That’s back the way we came. We’d be crazy to go back through there.

And I looked at Elmore and he looked at me. And we laughed, and I put the car in gear.

__________________________________

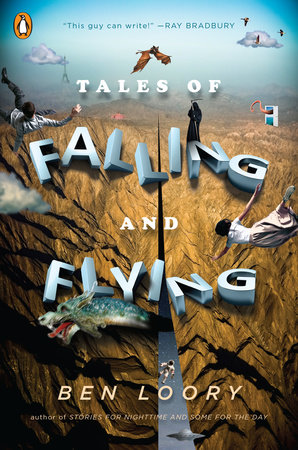

From TALES OF FALLING AND FLYING by Ben Loory. Used with permission of Penguin Books. Copyright © 2017 by Ben Loory.