Elizabeth Harrower, A Great Russian Master (from Australia)

Joan London in Praise of 'The Watch Tower'

I first read The Watch Tower in the library of the University of Western Australia 42 years ago. I must have found it while browsing the shelves of Australian fiction. I wasn’t taking a course on Australian literature—there wasn’t one. Even though I was enrolled in a course called the Modern Novel and was reading James Joyce and Ford Madox Ford—Virginia Woolf was the only female writer to merit a mention—I rarely read literary journals and had no real idea about the literary culture of my own country.

In spare moments I always ended up at the fiction shelves of the library, looking for books that would speak to me about my life and fate. I relied on random discoveries. The Watch Tower, published by Macmillan in London in 1966, would have been a relatively new acquisition.

The novel gripped me like a nightmare. It had the strong, lively, unflinching writing of someone with a story to tell, who goes deeper and deeper into the characters, their feelings and motives, as the narrative races along. Its scenes were vivid, of Sydney in the 1940s and 50s with its bright air and glittering bays, and the house with the view, and the man who patrols it like an evil dwarf, rolling his eyes and rubbing his hands over some new way to torture his wife. I didn’t know… I remember thinking that. I meant: I didn’t know there was writing like this, in Australia, now, by a woman. I read it as if it were a thriller, obsessively, though no one is murdered. There is only, like the title of another great novel of psychological cruelty, the death of a heart.

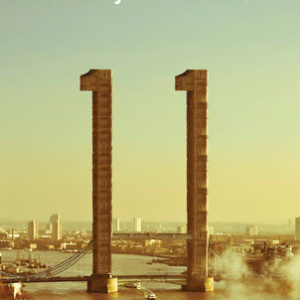

The title itself had a contemporary resonance, provided by Bob Dylan’s song ‘All Along the Watchtower’, released a year later: There must be some way out of here…

For that is what the novel is about. Entrapment, and finding the way out. Or not.

The novel’s opening line, ‘Now that your father’s gone—’, has the ring of once upon a time in a fairytale, announcing an eternal theme in the history of storytelling, especially the novel, the fate of single women without a man in the family, or independent means.

Their selfish mother, more like a wicked stepmother, takes her two daughters, Laura and Clare, out of boarding school, to live with her in a flat in Sydney. Laura, the older by seven years, a promising student who wants to become a doctor, is sent to business college to learn shorthand typing and then, according to the rites of passage in those days, cuts off her plaits and becomes a secretary at a cardboard box factory, for the enigmatic owner, Mr. Felix Shaw. ‘She had a sensation of having mislaid… a piece of herself. There was nothing to dream!’

WWII breaks out, and their mother leaves on the last ship home to England. orphaned, friendless, the sisters must move into a boarding house and fend for themselves. Sensitive, moral, intelligent, penniless girls, they are heroines worthy of Henry James, Jane Austen or Charlotte Brontë. To save Clare from leaving school at 14 to work with her in Mr. Shaw’s next enterprise, a chocolate factory, Laura agrees to marry him.

‘Mmm.’ He moved his mouth ruminatively, never quite displacing that superior smile and its odd suggestion of complicity. Again he hummed out that long reflective noise. ‘I don’t know if we couldn’t fix that up.’

Laura was aware suddenly that her eyes felt strained and sore; the skin of her lips felt taut and cracked with the heat. talking in this personal way to Mr. Shaw made her feel nervous and giddy, or just peculiar and unlike herself.

Thus the elder sister, traditionally the surrogate mother, offers up her life for a home and security, and to give the younger a chance. Handed over by an unloving mother to a man unable to love, Laura has been groomed for victimhood. Because she is a principled person, she feels in debt to him. ‘She had only herself, and out of herself she had somehow to manufacture repayments he would find acceptable.’ How she toils! Chores abound in this mansion, as Laura, after a day in the of office, scrubs and serves and weeds the garden, and won’t ask for a penny for herself. A young woman in wealthy surroundings, she has faded dresses and worn hands.

Mr. Shaw becomes Felix, ‘a swarthy, nuggety man of 44… hardly taller than Laura in her two-inch heels… his voice grated and rasped as if his throat was perpetually rough from shouting.’ He has a particular physical presence in the novel, his gestures and speech and ‘his restless dark-brown eyes, the pores of his tough skin, his wrinkled sinewy throat and his, in some way, horribly incongruous, imported, impeccable clothes.’

Soon after the marriage he goes back on his word. Clare must leave school after all and go to business college.

Endlessly, as if for sport, he invents ways in which to squeeze the joy out of Laura’s life. He insists on Clare’s constant presence too, ‘to have her there to be knocked down, as it were, by the blows from his eyes and his words.’

Clare, a lover of Chekhov, Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy, isolated in that house, ‘where there had never been a friend to call… only ever the indifferent, papery sound of wind in trees, distant traffic, winking planets,’ feels herself to be ‘the only Russian in Sydney.’

I never forgot The Watch Tower. The vision of the book, the sense of darkness in sunlight, stayed lodged somewhere at the back of my mind. I remembered the experience of reading it as intense, though disturbing sometimes; in the sure hand of the creation of its villain, there was panache, even humor.

It’s always instructive to return to a book you admired a long time ago. It carries the ghost of the first reading. Even though we now have words like misogyny and abuse and co-dependence to name the forces that entrap the sisters, the tension is undiminished.

How a well-meaning young woman, brought up to be considerate of others, is harnessed to the demands of a damaged man is still excruciating to read four decades later. Who in the course of a life has not endured, or witnessed, or participated in the attempt of one human being to have power over another? Harrower’s relentless observation of this process and its effects is worthy of the Russian masters.

‘Little by little,’ thinks Laura in a rare moment outside Felix’s radar, ‘she had resigned away the trust she had been given to be herself—out of pity, from a desire for peace at any price, thinking nothing really lost, anyway, by her silent acquiescence.’

To be herself. Unlike Laura, Clare has never signed away an inner life. Hers is the view from ‘the watch tower,’ on guard for danger but also looking out at the world from a contemplative distance. Reality. That is her quest.

This permanent awareness of what was so, regardless of her whims of the moment, regardless of what it would be pleasant to believe, or not pleasant, this solid bedrock was what she was, what she was about. What could there be in its place if you were differently constituted?

This awareness includes the acknowledgement of otherness, the respect for another’s being. Sometimes there is joy, rapture, in light, or trees, or the humanness of strangers, but its practice is as austere as any other form of spiritual exercise.

What I had forgotten from my first reading, or perhaps was not ready to receive, is the strength of this slowly gathering counter-force, the means of resistance to the malevolence of Felix Shaw.

The assistance Clare offers Bernard, the young Dutchman, survivor of the war in Europe, is like the breaking of a spell. Suddenly she sees that ‘she and Bernard had traversed the same extreme country.’ It had never occurred to her that she could be useful to anyone. ‘Yet she felt extraordinarily light-hearted—like a scientist at the very moment of discovery… there was boundless vitality of the spirit, a thoughtfulness beyond words. She could encourage someone to stay alive. And this was what she was for.’

Again and again harrower defines the ways of the victims, the helpless. The Watch Tower is an extended study of suffering, whatever its origin. It is Bernard who has the last word on Laura as he watches her frantic search for the diamond ring that Felix has allowed her to believe she has lost.

Laura had forgotten him, was unaware of his eyes on her, was so far removed from the light movement of the air, the scent of freesias, the shimmering of leaves, that she suddenly seemed to Bernard, who had seen many victims, to represent them all. She was unapproachable as the condemned are unapproachable and he was responsible, as the free always are.

Where does such knowledge come from? Each of Harrower’s four novels is concerned with entrapment of one sort or another, through family or youth or love. But The Watch Tower, her last novel, is almost like a distillation in its vision of the forces of good and evil.

Something runs clear and strong through this wonderful, painful novel, the dark and the light. The victim and the survivor. Suffering and joy. The knowledge of both. Reality.