Elias Khoury's Unique Vision of Civil War Lebanon

Abdo Wazen on Lost Memories in Lebanese Literature

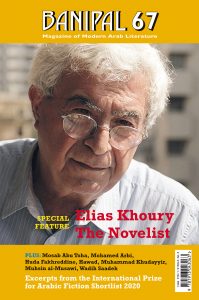

The following is from issue 67 of Banipal, and is part of a larger feature on “Elias Khoury the Novelist,” the celebrated Lebanese and international author who published his first novel in 1975 and, along with Naguib Mahfouz, is the most translated Arab author into English and other languages. It opens and closes with translations from Khoury’s latest and his first novels respectively, and includes a number of essays on the corpus of novels, and reviews.

Abdo Wazen writes about Khoury’s early works, written during and about the Lebanese Civil War (1975–1990). Khoury’s writing of the “war novel,” Wazen writes, pioneered a new and “second beginning” for the Lebanese novel. This is described in detail in his analysis of The Journey of Little Gandhi with the lost memories of both Little Gandhi and his city of Beirut.

*

Novelist Elias Khoury is deemed a trailblazer in the writing of the Lebanese war novel, as well as a pioneer of what might be termed the Lebanese novel’s “second beginning.” The pre-civil war novel was the province of a mere handful of writers, foremost among them the late Tawfiq Yusuf Awwad and Yusuf Habashi al-Ashqar. Awwad anticipated the war’s outbreak in his celebrated novel Tawahin Bayrut (1972, Death in Beirut, 1976), while al-Ashqar foresaw the period of change that would accompany the war in his equally celebrated 1971 novel La Tanbut Judhur fi al-Samaa’ (Roots Don’t Grow in the Sky).

Not long after Lebanon’s civil war erupted in 1975, the features of an entirely new Lebanese novel began forming on the horizon. This “new” novel took as its starting point the realities and contradictions of the war and the thorny questions it raised on the intellectual, ideological and sectarian levels.

Elias Khoury, who fought on the side of the Leftist front that sought to change the sectarian, classist and tribal system and defend the Palestinian cause, appears to have been the first to take up the writing of war literature and, more specifically, the war novel.

Based on narrative sequence, Khoury’s novel Little Mountain was the first building block in the foundation of the new novel. This was followed by a succession of novels by Khoury and other writers, both veteran and emerging, for whose work the war provided the impetus, the raw material, and the temporal and spatial setting.

Individuals only encounter one another via their differences, where difference is the hidden essence of the movement of separation.

A number of Khoury’s works have been viewed as particularly significant for the way in which they reread the war’s tragedies, contradictions and absurdities, while drawing on the battlefield for their characters and events. Among these pioneering novels are White Masks (1981), The Journey of Little Gandhi (1989), The Kingdom of Strangers (1993), Majma‘ al-Asrar (1994, Complex of Secrets), and Yalo (2002), which marked one of the all-time high points of Lebanese war literature.

In The Journey of Little Gandhi, the individual unconscious overlaps with the collective unconscious, such that the individual who lives (or dies) on the fringes of society becomes the image of a group which itself lives a marginalized existence. For the group is a set of scattered individuals who fail to realize the ties of unity that bind them, and who make no attempt to interpret their encounters, be they momentary or enduring. The individual has a profound sense of his “individuality” or “aloneness,” which is the ideological (or, perhaps, the metaphysical) face of the loneliness which he suffers within the community.

Individuals only encounter one another via their differences, where difference is the hidden essence of the movement of separation which causes the individual to be anxious in a locale whose parts do not hold together. It will thus come as no surprise that “place” in Elias Khoury’s novel becomes a kind of mosaic which is in constant danger of disintegrating. The city of Beirut is the more refined exemplar of the jolting and scattering of place, and the ideal expression of the mosaic-like nature of an entire homeland.

Elias Khoury records “little Gandhi’s” life story as told by Gandhi to Alice, and as told by Alice to the writer—the narrator—as though the narrative were a missing link within other missing links. The life story of Gandhi the shoe shiner is, above all, the life story of the city, which becomes apparent through the eyes of Gandhi and his simple, inconsequential relationships. Alice’s memory, which recovers the threads of stories, events and faces, appears to be part of the city’s lost memory.

Thus, if Alice’s memory has been scattered and has lost a clear sense of time, this is because Beirut’s memory has likewise been scattered, having lost the ability to recover the past with its fragmented images and features. Relying as it does on Alice’s memory, which is threatened with failure and oblivion, the novel is the narrative of “lost memory,” as Khoury has stated in more than one context.

Not surprisingly, then, the novel’s structure is scattered among memories, as images fly every which way in the storm that has blown up over the city and left it in ruins. Even so, when the writer steps back from Alice’s account, he weaves a narrative fabric which, despite its torn appearance, is nevertheless cohesive. The memories which are not joined by a single temporal context, but which overlap and evoke one another via a state of temporal chaos emerging from the depths of oblivion, quickly coalesce into a single semantic context which transcends its narrow temporality into a broader psychic-existential time.

This broader, psychic-existential time is the time of the lost characters, the time of Beirut, which may never have been anything but the illusion of a city. After all, Beirut is “a city without a history,” Alice admits. Through Gandhi’s story and the relationships that connected him to the other characters who surrounded him during a certain period of time, the writer attempts to create a history for the city whose history is being lost.

So Beirut, then, misses a single specified time, and drowns in an ambiguity of times, with history repeating itself, and one decade blurring into another. Time quickly loses its logic, alternately closing and opening, slowing down and speeding up, advancing and retreating as dictated by the act of remembrance and the presence of memory with its countless dimensions. This is the Beirut of varied faces, the Beirut of night and day, the Beirut of sects, the Beirut of obsessions and successive wars, the Beirut of the East-West mosaic, a refuge for misfits, and for big ideas that clash to infinity.

Characters and faces multiply as though they were phantoms peering out from the darkness of memory, and when memories emerge from the inner darkness, they are naturally disposed to be hazy and ambiguous, causing actual places to appear illusory, imbuing events with an air of mystery, and rendering faces little more than dimly lit silhouettes. Gandhi’s character, however, remains central—albeit counterbalanced by that of Alice, who embodies a second axis which overlaps with Gandhi’s.

While Beirut was under siege, little Gandhi had nearly lost his memory.

At times Gandhi’s life appears to be a muddled expression of that of Alice, who recounts his story mingled with her own, yet with neither of the stories completing the other. Different as they are, the two stories are both important parts of the city’s history. The numerous characters that emerge, develop, and fade on the margin of Gandhi’s story are quite interesting: at once realistic and bizarre, typical and atypical, clinging to the city’s reality even while distancing themselves from it. Corrupt, backward and hackneyed, however pristine they appear at times, they live through the city’s transformations and suffer from both inward alienation and genuine exile.

Some of them are rooted in the geographical spot, while others have no roots. Characters, or ghosts of characters with nebulous features, appear and disappear like the stuff of dreams or, rather, of nightmares. Given the feverish rush that permeates the novel, and the vertigo that afflicts the “investigation,” it would have been possible to invent other characters, any characters, and to have made them say anything.

Were we to pause before little Gandhi’s story as narrated by him, by Alice, and by the writer, we would find that it is nothing but the dull story of a dull man who exhibited no heroic qualities. Rather, he was an insignificant person, defeated, who recalled nothing of his absent past apart from a few scattered images and who, during the last phase of his life, worked as a shoe shiner at the gates to the American University of Beirut.

If the novel’s opening scene is that of Gandhi’s bullet-ridden corpse during the 1982 Israeli invasion, this is because his death embodies that of the witness who has seen everything in utter silence. Alice has pronounced him dead and, bullets filling the air, has covered his body with newspapers. The narrator assumes that before dying as a martyr for a cause that mattered little to him and that he hardly understood, Gandhi “had opened his eyes and seen nothing”, and that “he didn’t know anymore whether he was seeing, or dreaming”.

While Beirut was under siege, little Gandhi had nearly lost his memory. The narrator tells us that “all he remembered about the days of the blockade was that he had forgotten everything.” In fact, “he’d begun forgetting everybody’s name,” as though in anticipation of his gruesome death. He kept saying that “all it means to live anymore is to be waiting to die,” and at the moment of his passing, Gandhi knew that “the bullets weren’t aimed at him. Rather, they were aimed at the heart of a city that had destroyed itself.”

As the narrator reminds us, Gandhi had witnessed Beirut’s day-by-day destruction. In fact, he had sensed it deep down before it actually happened, intuiting the gloomy end that threatens all things.

Translated from the Arabic by Nancy Roberts

__________________________________

From Banipal 67. Reproduced with permission. Copyright © 2020 by Abdo Wazen.

Abdo Wazen

Abdo Wazen, the Lebanese poet, literary critic and translator, is one of the best known literary editors and critics in the Arab world. He is presently literary editor of the online Independent Arabia, after serving as cultural editor of Al-Hayat newspaper for many years until its demise. He is a poet, a translator of French poetry into Arabic, and in 2012 won the Sheikh Zayed Book Award for Children’s Literature for his book The Boy Who Saw the Color of Air.