Translated by Lucas Zwirner

Among the words that have long lain in helpless exhaustion, shunned and hidden away, words that one made a mockery of oneself by using, words that were so drained of meaning that they shriveled and became ugly warnings—among these one finds the word “poet.” And any person who still took up the activity of writing, which continued to exist as always, called himself “someone who writes.”

One might have thought that writing meant abandoning false claims, setting new standards, becoming stricter with oneself, and above all avoiding everything that leads to spurious success. In reality, the opposite occurred. The same people who mercilessly attacked the word “poet” developed their own style of sensationalism. They pathetically proclaimed that literature was dead and printed their small-minded idea on expensive paper, as if this claim were somehow worth considering.

Naturally, their particular case soon drowned in its own ridiculousness, but other people—people who weren’t yet barren enough to wear themselves out with proclamations, and who instead penned bitter if intelligent books—soon gained the reputation of “people who write.” They did what poets had done before them: they wrote the same book again and again instead of remaining silent. And regardless of how imperfect and deserving of death mankind seemed to them, one task still remained for men: to applaud those who write.

Anyone who didn’t want to do that, anyone who had grown tired of the endlessly repeated outpourings, was damned twice: once as a human—humans were already lost—and then as someone who refuses to acknowledge the endless obsession with death—the writer’s obsession with death—as the only obsession that has any value whatsoever.

Because of all this, I’m no less suspicious of those who merely write than I am of those who self-indulgently continue to call themselves poets. I see no difference between the two; they resemble each other like drops of water, and they consider the recognition they once received an irrevocable right.

In truth, nobody today can be a poet if he doesn’t seriously doubt his right to be one. Anyone who fails to recognize the condition this world is in can hardly have anything to say about it. The perilous state of the world, once the primary concern of religion, has been pushed into the realm of human affairs, and those who aren’t poets watch the world’s destruction (more than once rehearsed) with calm composure. There are even some among them who have calculated the world’s prospects and profit from its decline, making it their profession, fattening themselves upon it. Prophecies have lost all value ever since we entrusted them to machines; the more we chip away at ourselves, the more we place our trust in lifeless objects and the less control we have over what happens to us.

Our growing power over everything—lifeless as well as living—and especially over ourselves, has become a countervailing force that we only appear to be in control of. Hundreds, even thousands of things might be said about this, but they are all well-known. That’s the most surprising thing about this loss of control: its every detail has become a daily news item, a wicked banality. No one needs me to repeat it all. Today, I have undertaken something else, something more modest.

Given the current state of the world, it might be worthwhile to think about whether there’s still some way a poet (or what we have until now considered a poet) could make himself useful. After all, despite the fatal blows that the word “poet” has suffered due to poets themselves, some part of the word’s claim still remains. Whatever literature is, it is certainly not less than the people who cling to it still: it isn’t dead. But what might the lives of its representatives look like today, and what do they have to tell us?

By chance, I recently stumbled upon a note by a writer whose name I can’t provide because nobody knows who he is. This anonymous note is dated August 23, 1939, a week before the outbreak of the Second World War. It reads: “It’s all over now. If I were really a poet, I’d be able to prevent the war.” Today we think this is silly, now that we know what has happened. What arrogance! What could a single man have prevented? And why, of all men, a poet? Can we imagine anything more unrealistic? And what distinguishes this sentence from the bombast of those who deliberately used their own sentences to incite the war?

First, I read the note with irritation, and then with increasing irritation I wrote it out. Here, I told myself, is what I find most repulsive about this word “poet”—an ambition that stands in blatant contradiction to what a poet might actually be capable of accomplishing. In short, the note was an example of the silly babble that discredits the word “poet” and fills us all with mistrust the moment we see someone who claims that title pound his chest and tell everyone about all the great things he’s going to do.

But then, in the days that followed, I noticed to my surprise that the sentence wouldn’t leave me alone—it was stuck in my head, I returned to it, rearranged it, pushed it away, pulled it back in again, as if it depended on me, and me alone, to make sense of it. The beginning of the note was strange: “It’s all over now.” An expression of absolute and hopeless defeat at a time when victories were expected. While everything was geared toward victory, this sentence already gave voice to the desolation of defeat, as if it were unavoidable. On further inspection, the main part of the note—“If I were really a poet, I’d be able to prevent the war”—seemed to express precisely the opposite of empty babble: namely, a confession of utter failure. But more than that, it conveyed a sense of responsibility, and—this is the astonishing thing—it did so in a situation that had nothing to do with responsibility in the proper sense of the term.

Given the current state of the world, it might be worthwhile to think about whether there’s still some way a poet (or what we have until now considered a poet) could make himself useful.Here, I realized, is someone who evidently means what he says because he says it in silence, and in saying it he accuses himself. He doesn’t assert his claims; he relinquishes them. In his despair over what is now inevitable, he convicts himself and not those who actually caused the situation—people whose identities he certainly knows, because he would be more optimistic about the future if he’d remained ignorant of them. Thus, only one source of my original irritation remains: the idea this person had about what a poet is, or should be, and the fact that he considered himself a poet up until the moment when, with the outbreak of war, everything collapsed.

It is precisely this irrational claim of responsibility that gives me pause and impresses me. Still, it seems appropriate to add that it was through words—the conscious and habitual employment of abused words—that a situation arose in which war became inevitable. If so much can be accomplished through words, why can so little be impeded by them? It isn’t so surprising that a person who occupies himself with words more than other people do would also expect more of them than others.

A poet must be a person (and maybe I was too hasty in seeing this) who holds words in especially high regard and who likes to dwell among them, maybe even more than he likes to dwell among humans; a person who, though he surrenders himself to both words and men, trusts words more. He may even drag lonely words down from their lofty heights in order to reintroduce them into the world with great force. He investigates words and touches them; strokes, scratches, pets, and paints them; and even after playing all his private games with them, remains able to cower before words in awe. Even when he seems to misuse a word (which he often does), he does so only out of love.

Behind all this play, there’s a force that even he doesn’t always understand, one that is most often weak but sometimes so overpowering that it tears him apart. It is the desire to be responsible for everything meaningful in words and to make himself, and himself alone, answerable for their failure.

But what good is it—this act of taking fictive responsibility for others? Isn’t it lacking real power precisely because of its falseness? I believe that even the most limited minds take more seriously what a man imposes on himself than what others force upon him. And we are never closer to an event, we never have a more intimate relationship to an event, than when we feel responsible for it. If the word “poet” has been emptied of meaning for some time now, it’s because people have attached a certain kind of frivolousness to it—poetry was something that withdrew from the world in order to smooth the way for itself.

And the clear connection between arrogance and aesthetics, right at the beginning of one of the darkest periods of mankind’s history (which poets didn’t recognize even when it was already upon them), wasn’t capable of inspiring much respect. The poets’ misguided trust in things, their misjudgment of reality (which they approached with contempt and without insight), their denial of every connection to reality, their inner disconnect from everything real that was happening around them—since there weren’t many facts in the language they were using—owing to all of this, we can easily understand why eyes that looked closer and harder than most turned away from so much blindness in horror.

Against all this, we have to remember that sentences like the one that obsessed me still exist. As long as there are some sentences (and there are certainly more than one) that take the responsibility for words upon themselves, and in the event of total collapse feel this responsibility to the utmost, we still have the right to hold on to a word—poet—that has always been used to describe the authors of the works that define our species. Without these works we wouldn’t know what we amount to. They nourish and sustain us no less than our daily bread, though theirs is a different nourishment. And if nothing else were left us, if we didn’t even know how completely these works have shaped us, then, searching in vain for something in our time that equals them, we would still find one option available: if we were very strict in judging our age, and even more so in judging ourselves, we could admit that we have no poets today, and yet ardently continue to wish that we did.

This sounds very grand, and it has little significance if we don’t clarify what a poet has to offer us today that would merit the title.

First and foremost, I would say that a poet preserves metamorphosis—he preserves metamorphosis in two different ways. On the one hand, the poet would make the literary legacy of mankind, which is rich in metamorphoses, his own. We are only today beginning to understand how rich this legacy is, now that nearly all the texts of earlier cultures have been deciphered. Up until well into the nineteenth century, anyone who was concerned with this truest and most enigmatic aspect of mankind—the power of metamorphosis—was limited to two examples from antiquity.

The later one, Ovid’s Metamorphoses, provides a nearly systematic collection of all the well-known mythic, “higher” metamorphoses. And the second, earlier work, The Odyssey, is concerned with the adventurous metamorphoses of one mortal, Odysseus. The apex of all his metamorphoses is reached when he returns home as a beggar, which is the lowest rank imaginable. No subsequent poet has achieved, let alone improved upon, the completeness and perfection of his disguise. It would be ridiculous of me to try to treat the influence of these two works on European culture before, and especially after, the Renaissance.

Ovid’s Metamorphoses appears in the writings of Ariosto and Shakespeare, as well as in the works of countless others, and it would be foolish to think that it has ceased to have an effect on us moderns. We still encounter Odysseus today: he is the first character to have entered the core of world literature, and it would be hard to name more than a handful of other characters who have had as great an impact.

If so much can be accomplished through words, why can so little be impeded by them?Though Odysseus was the first of these omnipresent characters, he is by no means the oldest; one older has been found. It has scarcely been one hundred years since the Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh was discovered. The epic begins with the metamorphosis of Enkidu—a man in a state of nature who lived with animals—into a civilized and cultured man, a theme that concerns us today as we now have concrete and precise accounts of children who were raised by wolves. The epic ends with Enkidu dying, leaving his friend Gilgamesh alone, preparing for a monstrous confrontation with death—the only confrontation that doesn’t leave modern man with a bitter aftertaste of self-deception.

Here I offer a piece of evidence from my own life as an unlikely example: no work of literature, literally not a single one, has been as critical in determining my path as that four-thousand-year-old epic that no one knew about just over a century ago. I first encountered it at the age of seventeen, and I haven’t forgotten it since. I have returned to it like a bible, and in addition to the effect it had on me personally, it has also filled me with anticipation for something as yet unknown to our culture. It is impossible for me to consider the canon that has been passed down to us and nourished us as final. And even if it turns out that no written work of the same importance is ever created again, there still remains the enormous reservoir of orally transmitted works by earlier peoples.

There is no end in them to the metamorphoses that concern us here. We could spend a lifetime contemplating and reconstructing them, and that life would not have been badly spent. Tribes often made up of fewer than one hundred people have left behind riches that we surely don’t deserve. We are to blame for their extinction, and they continue to die out because of our carelessness.

They preserved their myths until the end, and the paradox is that hardly anything in existence has proved more useful, hardly anything fills us with as much hope, as these early, unparalleled poems by people who have been hunted, damned, and plundered by us until they collapsed into misery and bitterness. They—the people we scorned for their simple culture, and who we blindly and mercilessly exterminated—have left behind an inexhaustible intellectual legacy. We cannot thank the scholars enough for saving it. The preservation of this work, its resurrection within our lives, is the poet’s task.

I have portrayed poets as conservators of past metamorphoses, but they are conservators in another way as well. In a world so invested in achievement and specialization, a world that recognizes nothing but the very pinnacle of success, which it approaches as a type of logical consequence; in a world that turns all its strength toward the cold solitude of the peak and disregards and erases anything beneath it—the multitude, the real—because it doesn’t contribute to the peak; in a world where metamorphosis is increasingly forbidden because it contradicts the sole purpose of production, which recklessly multiplies the means of its self-destruction and strangles everything innate in men that might oppose it—in such a world, which one might like to describe as the blindest of all worlds, it seems of cardinal importance that there are still some of us who, in spite of this world, continue to practice the art of metamorphosis.

This, I think, is the actual task of the poet. A poet should try, no matter the cost, to preserve a gift that once was inherent but now has atrophied, and he should do so in order to keep open the doors between people—himself and others. He must be capable of becoming everyone: the smallest, the most naive, the most powerless. But this desire to experience others from within can never be determined by the goals that compose what we call our normal or official lives. This desire would have to be completely free from any hope of success or achievement; it would have to constitute its own desire: the desire for metamorphosis.

An always-open ear would be necessary. But that alone isn’t enough. Most people today can barely express themselves in language. Increasingly, they repeat the same clichés from newspapers and other mass media without actually meaning anything at all. Only through metamorphosis in the most extreme sense of the word—which is the sense I’m using here—would it be possible to feel what a man is behind his words, to grasp the continued existence of what is alive. This is a mysterious process, one which is hardly ever explored, and yet it is the only true path to other people.

I have tried in various ways to give a name to this process—it is roughly what we used to call “empathy”—and I am using this formidable word “metamorphosis” for reasons I don’t have time to get into here. But whatever we call this process, no one would deny that something real and very precious is at stake. In this ongoing practice, in this compelling experience of the full range of humanity—especially that part of humanity that draws the least attention to itself—in this restless practice not withered or crippled by any system, I see the poet’s actual profession. It is conceivable, even likely, that only a sliver of this experience makes its way into his work. How one judges this work—which again belongs to the world of prestige and the pinnacle—is not our concern. Today we are interested in grasping what a poet would be, if a poet existed, not in judging the work that a poet leaves behind.

A poet should try, no matter the cost, to preserve a gift that once was inherent but now has atrophied.If I disregard everything that has to do with success, if I actively mistrust it, I do so because it comes with a danger that is left to each person to know for himself. The drive toward success, like success itself, has a constricting effect. Someone whose sole concern is achievement considers everything that doesn’t help him attain his goal as deadweight. He throws it all away, and so becomes more efficient. It doesn’t worry him that he may be throwing away the best in himself because he regards achievement as more important. He swings himself ever higher, from place to place, and measures the distance he has covered. Position is all; it is determined from outside himself, and he doesn’t create it. He has no part in it. He sees it and strives toward it. But however useful and important these efforts may be in many areas of life, for the poet, as we would like him to be, they are utterly destructive.

Because above all else, the poet must make more and more space within himself: space for knowledge—knowledge that he doesn’t acquire for any specific goal—and space for people, whom he experiences and incorporates through the process of metamorphosis. As far as knowledge itself is concerned, he can acquire it only through the clean and honest processes that determine all systems of knowledge. But among the many different branches, which may lie far apart, he is guided not by any conscious rule, but instead by an inexplicable hunger.

Given that he simultaneously opens himself up to people of vastly different experience and understands them through the oldest of prescientific methods—metamorphosis—given that he is thereby in a constant state of inner turmoil that never abates because he can define for it no goal—he does not collect people; he does not systematically set them side by side; he merely encounters them and incorporates them as they come and as they are—and given the sudden jolts of feeling caused by these encounters, it is likely that sudden swerves in direction toward new branches of knowledge will occur.

I know how disconcerting this prescription might seem. It will inevitably be criticized. It sounds as if the poet aims solely at chaos and at being at odds with himself. For now, I have little to put forward against this charge—it is a very substantial one indeed. The poet is closest to the world when he carries this chaos inside of himself, yet—and this is the assumption we began with—he feels responsible for it. He does not approve of it. He does not feel good carrying it. He does not feel powerful or expansive because he has room for so much that is loose and opposed. He hates this chaos. He hates it, but he doesn’t abandon the hope that he may overcome it for others and thus for himself.

If a poet wants to say anything meaningful about the world, he must not push the world away from himself or seek in any way to avoid it. Despite the best of plans and intentions, the world is more chaotic than ever, and this chaos is pushing it with increasing speed toward self-destruction. The poet must carry this chaos as such—not smoothed and polished ad usum Delphini—but in such a manner that he does not fall under its spell. Through his experiences, he must oppose it from within and set the force of his hope against it.

But what is this hope? And why is this hope worth something only when it feeds on metamorphoses—earlier metamorphoses born out of the excitement of his readings, or contemporary metamorphoses, which he appropriates for the modern world through his openness? On the one hand, the violence of these characters occupies him, and they never relinquish the space they have claimed within him. They act through him, as though they were the sum total of his being. They compose at least the principal part of his being, and since they live in him, conscious and articulated, they are his resistance against death. One property of orally transmitted myths is that they demand to be retold. But their continued existence has its roots in their cultural specificity, so it is also characteristic of them not to change.

Thus, it’s possible to discover what their vitality consists of in each individual telling, and perhaps we have looked too infrequently at what enables them to be retold and passed along. It might be possible to describe what happens to someone who encounters a myth for the first time, but a complete description from me would be impossible, and a partial description would be pointless. I want to note only one thing: the feeling of certainty and incontestability imparted by myths, which is to say: that was how it was; it could not have been any other way. Whatever it is that myths communicate—however implausible the events would appear in any other context—in each individual retelling of the myth, our experience of it is free from doubt, and the myth assumes one unmistakable form.

This reservoir of certainty has been passed down to us, but has been abused for the strangest purposes. We know the political forms of this abuse all too well. These inferior uses deform, dilute, and tear at this certainty as they grasp and clutch at myths until they finally break. The abuses in the name of science are of a completely different nature. I will name only one obvious example: whatever we think about the truth of psychoanalysis, it has derived a good part of its power from the word “Oedipus.” The serious critique of psychoanalysis, which has only just begun, takes aim at precisely this word.

We can explain the aversion to myths in our time through the many abuses that have accompanied them. We feel that they are lies because we know only abuses, so we cast them both aside. What they have to give us by way of metamorphosis appears untrustworthy, and we recognize only those wonders in them that have been made real through technological innovations. We fail to give myths their due as the original sources of all our ingenuity.

But beyond all specific cases, what constitutes the core of myths are the metamorphoses they contain. It is through these metamorphoses that man created himself. Through them he made the world his own; through them he shares a bond with the world. It’s easy to see that he owes his own power to metamorphosis, but he owes to it something better still—his compassion.

If a poet wants to say anything meaningful about the world, he must not push the world away from himself or seek in any way to avoid it.It’s important not to shy away from a word that seems deficient to those who study the humanities. Compassion—and this is also a product of specialization—is increasingly being relegated to the realm of religion, which has assigned it names and overseen its operation. Compassion is being kept far away from the objective decisions of our daily lives, with the result that these decisions are becoming more technical.

I have said that a poet can be only someone who takes responsibility upon himself, even if he can do little to prove that he in fact has through his actions. His is a responsibility for life— life which is destroying itself—and we should not be ashamed to say that the responsibility is nourished by compassion. This responsibility is worthless when proclaimed as an undefined or general feeling. Rather, it must serve as a call for actual metamorphosis in every living individual.

Through myth, through past literature, the poet learns and rehearses this metamorphosis. The poet is nothing if he does not ceaselessly apply myth to the world around him. The thousandfold life that enters him, though by all appearances it remains separate from him in all its manifestations, does not collapse into a conceptual category. Instead, this life gives him the strength to stand against death and thereby becomes something universal.

The poet’s task cannot be to deliver mankind unto death. The poet, who opens himself to everyone, will experience with dismay the growing power of death in many people. He will grapple with death and never capitulate even if his efforts appear in vain. With pride he will withstand the envoys of emptiness that proliferate in our literature, and he will fight them with his own weapons. He will live by a law that has not been made for him but is his own. And it is this:

Let him push no one into nothingness who would gladly dwell in nothingness. Let him search for nothingness only in order to find the way out of nothingness and show that way to everyone. Let him remain in sorrow and despair so as to know how to pull others out of sorrow and despair, and not begrudge creatures their happiness, even though they claw and maim and tear one another apart.

_____________________________________

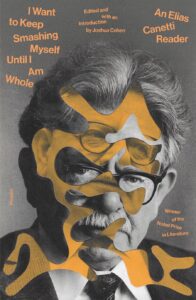

Excerpted from I Want to Keep Smashing Myself Until I Am Whole: An Elias Canetti Reader by Elias Canetti. Translated by Lucas Zwirner. Copyright © 2022. Available from Picador, an imprint of Macmillan.