So lonely! Shyly they glanced at each other across the dining room table in whose polished cherrywood surface candle flames shimmered like dimly recalled dreams. One said, “We should purchase a RepliLuxe,” as if only now thinking of it, and the other said quickly, “RepliLuxes are too expensive and you hear how they don’t survive the first year.”

“Not all! Only—”

“As of last week, it was thirty-one percent.”

So the husband had been on the Internet, too. The wife took note, and was pleased.

For in her heart she’d long been yearning for more life! more life!

Nine years of marriage. Nineteen?

There is an hour when you realize: here is what you have been given. More than this, you won’t receive. And what this is, what your life has come to, will be taken from you. In time.

* * * *

“A cultural figure! Someone who will elevate us.”

Mr. Krim was a tax attorney whose specialty was corporate law/interstate commerce. Mrs. Krim was Mr. Krim’s wife with a reputation for being “generous”—“active”—“involved”— in the suburban Village of Golders Green. Together they drove to the mammoth New Liberty Mall twenty miles away where there was a RepliLuxe outlet. This was primarily a catalogue store, not so very much more helpful than the Internet, but it was thrilling for the Krims to see sample RepliLuxes on display in three dimensions. The wife recognized Freud, the husband recognized Babe Ruth, Teddy Roosevelt, Van Gogh. It could not be said that the figures were “life-like” for they were no taller than five feet, their features proportionately reduced and simplified and their eyes glassy in compliance with strict federal mandates stipulating that no artificial replicant be manufactured “to size” or incorporate “organic” body parts, even those offered by eager donors. The display RepliLuxes were in sleep mode, not yet activated, yet the husband and wife stood transfixed before them. The wife murmured with a shiver, “Freud! A great genius but wouldn’t you be self-conscious with someone like that, in your home, peering into…” The husband murmured, “Van Gogh!—imagine, in our house in Golders Green! Except Van Gogh was ‘manic-depressive,’ wasn’t he, and didn’t he commit…”

Everywhere in the bright-lit store couples were conferring in low, urgent voices. You could watch videos of animated RepliLuxes, you could leaf through immense catalogues. Salesclerks stood by, eager to assist. In the BabyRepliLuxe section where child-figures to the age of twelve were available, discussions became particularly heated. Great athletes, great military leaders, great inventors, great composers, musicians, performers, world leaders, artists, writers and poets, how to choose? Fortunately, copyright restrictions made RepliLuxes of many prominent twentieth-century figures unavailable, which limited the choices considerably (few television stars, few entertainment figures beyond the era of silent films). The wife told a salesman, “I have my heart set on a poet, I think!

Do you have…” But Sylvia Plath wasn’t yet in the public domain, nor were Robert Frost or Dylan Thomas. Walt Whitman was available at a special discount through the month of April but the wife was stricken with uncertainty: “Whitman! Only imagine! But wasn’t the man…” (The wife, who was by no means a bigot, or even a woman of conventional bourgeois morality like her Golders Green neighbors, could not bring herself to utter the word gay.) The husband was making inquiries about Picasso, but Picasso wasn’t yet available.

“Rothko, then?”

The wife laughed saying to the salesman, “My husband is something of an art snob, I’m afraid. No one at RepliLuxe has even heard of Rothko, I’m sure.”

As the salesman consulted a computer, the husband said stubbornly, “We might get Rothko as a child. There’s ‘accelerated mode,’ we could witness a visionary artist come into being…”

The wife said, “But wasn’t this ‘Rothko’ depressed, didn’t he kill himself…” and the husband said, irritably, “What about Sylvia Plath? She killed herself.”

The wife said, “Oh but with us, in our household, I’m sure Sylvia would not. We would be a new, wholesome influence.”

The salesman reported no Rothko. “Do you have Hopper, then? ‘Edward Hopper, Twentieth-century American Painter’?” But Hopper was still protected by copyright.

The wife said suddenly, “Emily Dickinson! I want her.” The salesman asked how the name was spelled and typed rapidly into his computer. The husband was struck by the wife’s excitement, it was rare in recent years to see Mrs. Krim looking so girlish, so vulnerable, laying her hand on his arm in this public place and saying, blushing, “In my heart I’ve always been a poet, I think. My Loomis grandmother from Maine, she gave me a volume of her ‘verse’ when I was just a child. My early poems, I’d showed you when we first met, some of them…It’s tragic how life tears us away from…”

The husband assured her, “Emily Dickinson it will be, then! She’d be quiet, for one thing. Poems don’t take up nearly as much space as twenty-foot canvases. And they don’t smell. And Emily Dickinson didn’t commit suicide, that I know of.”

The wife cried, “Oh, Emily did not! In fact, Emily was always nursing sick relatives. She was an angel of mercy in her household, dressed in spotless white! She could nurse us, if . . .” The wife broke off, giggling nervously.

The salesman was reading from the computer screen: “‘Emily Dickinson (1830–1886), revered New England poetess.’ You are in luck, Mr. and Mrs. Krim, this ‘Emily’ is in a limited edition about to go out of print permanently but still available through April at a twenty percent discount. EDickinsonRepliLuxe is programmed through age thirty to age fifty-five, when the poet died, so the customer has twenty-five years that can be accelerated as you wish, or even run backward, though not back beyond age thirty, of course. Limited offer expires in…”

Quickly the wife said, “We’ll take it! Her! Please.” The wife and husband were gripping hands. A shiver of sudden warmth, affection, childlike hope passed between them in that instant. As if, so unexpectedly, they were young lovers again, on the threshold of a new life.

Even with the discount, EDickinsonRepliLuxe came to a considerable price. But the Krims were well-to-do, and had no children, nor even pets. “‘Emily’ will cost only a fraction of what a child would cost what with college tuition…” Mrs. Krim was too excited to read through the contract of several densely printed pages before signing; Mr. Krim, whose profession was the perusal of such documents, took more time. Delivery of EDickinsonRepliLuxe was promised within thirty days, with a six-month warranty.

The salesman said, in a tone of genial caution: “Now you understand, Mr. and Mrs. Krim, that the RepliLuxe you’ve purchased is not identical with the original individual.”

“Of course!” The Krims laughed, to show that they were not such fools.

“Yet some purchasers,” the salesman continued, “though it’s been explained to them thoroughly, persist in expecting the actual individual, and demand their money back when they discover otherwise.”

The Krims laughed: “Not us. We are not such fools.”

“What the RepliLuxe is, technically speaking, is a brilliantly rendered mannikin empowered by a computer program that is the distillation of the original individual, as if his or her essence, or ‘soul’—if you believe in such concepts—had been sucked out of the original being, and reinstalled, in an entirely new environment, by the genius of RepliLuxe. You’ve read, I think, of our exciting new breakthroughs in the area of extending the original life span, for instance, in the case of an individual who died young, like Mozart: providing MozartRepliLuxe with a much longer life and so allowing for more, much more productive work. What you have in EDickinsonRepliLuxe is a simulation of the historical ‘Emily Dickinson’ that isn’t quite so complex of course as the original. Each RepliLuxe varies, sometimes considerably, and can’t be predicted. But you must not expect from your RepliLuxe anything like a ‘real’ human being, as of course you know, since you’ve read our contract, that RepliLuxes are not equipped with gastrointestinal systems, or sex organs, or blood, or a ‘warm, beating heart’—don’t be disappointed! They are programmed to respond to their new environment more or less as the original would have done, albeit in a simplified manner. Obviously, some RepliLuxes are more adaptable than others, and some households are more suitable for RepliLuxes than others. The United States government forbids RepliLuxes outside the privacy of the household, as you know, for otherwise we might have public spectacles like a boxing match between ‘Jack Dempsey’ and ‘Jack Dempsey,’ or a baseball game in which both teams were made up of ‘Babe Ruth.’ Male athletes are our best-selling items though they are really not suited for private households since owners are forbidden to exercise them outdoors. Like Dalmations, whippets, greyhounds, they need to be exercised daily, and this has created some problems, I’m afraid. But your poet is ideal, it seems ‘Emily Dickinson’ never did go outdoors! Congratulations on a wise choice.”

In their dazzled state the Krims hadn’t followed all that the salesman had said but now they shook his hand, and thanked him, and prepared to leave. So much had been decided, in so short a span of time! In the car returning to Golders Green, the wife began suddenly to cry, in sheer happiness. The husband, gripping the steering wheel tight in both his hands, stared straight ahead wishing not to think What have we done? What have we done?

* * * *

To prepare for their distinguished houseguest, the wife bought the Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson, several biographies, and an immense book of photographs, The Dickinsons of Amherst, but most days she was too restless to sit still and read, especially she had trouble reading Dickinson’s knotty, riddlesome little poems, and so busied herself preparing a “suitable, climate-controlled environment” as stipulated in a RepliLuxe booklet, to prevent “mechanical deterioration” of the RepliLuxe in excesses of humidity/aridity. She acquired from antique stores a number of period furnishings that resembled those in the poet’s bedroom: a mahogany “sleigh” bed of the 1850s so narrow it might have belonged to a child, with an ivory crocheted quilt and a single matching goose-feather pillow; a bureau of four drawers, in rich, burnished-looking maple; a small writing table, and other matching tables upon which the wife placed candles. The wife found two straight-back chairs with woven seats, filmy white organdy curtains to hang at the room’s three windows, a delicately patterned beige wallpaper, and a milk glass kerosene lamp circa 1860. She could not hope to duplicate the framed portraits on Emily’s walls, which must have been of ancestors, but she located portraits of anonymous nineteenth-century gentlemen, similarly dour, brooding and ghostly, and amid these she hung a portrait of her grandmother Loomis who’d died many years ago. When at last the room was completed, and the husband had come to marvel at it, the wife seated herself at the impracticably small writing table, at a window flooded with spring sunshine, and picked up a pen and waited for inspiration, poised to write.

“‘I taste a liquor…’”

But nothing more came, just now.

* * * *

The first shock: Emily was so small. When EDickinsonRepliLuxe was delivered to the Krim household, uncrated, and positioned upright, the purportedly thirty-year-old woman more resembled a malnourished girl of ten or eleven, who barely came to the wife’s shoulder. Though the Krims had seen that even Babe Ruth had been reduced in size, somehow they weren’t prepared for their poet-companion to look so stunted. It seemed that the RepliLuxe had been modeled after the single extant daguerreotype of the poet, taken when she was a very young sixteen. Her eyes were large, dark, and oddly lashless, her skin was ivory-pale, smooth as paper. Her eyebrows were wider than you’d expect, heavier and more defined, like a boy’s. Her mouth, too, was unexpectedly wide and fleshy, with a suggestion of disdain, in that narrow face. Her dark hair had been severely parted in the center of her head and pulled back flatly and tightly into a knot of a bun, covering most of her unusually small ears like a cap. In a dark cotton dress, long-sleeved, ankle-length, with an impossibly tiny waist, EDickinsonRepliLuxe more resembled the wizened corpse of a child-nun than a woman-poet of thirty. The wife stared in horror at the lifeless eyes, the rigid mouth. The husband, very nervous, was having difficulties, as he often did with such devices, with the remote control wand. There were numerous menu options, he’d begun striking numerals impatiently.

“‘Sleep mode.’ How the hell does it ‘activate’…” By chance the husband must have struck the right combination since there came a click and a humming sound from EDickinsonRepliLuxe and after a moment the lashless eyes came alive, glassy yet alert, darting about the room before fixing on the Krims standing perhaps five feet away from the figure. Now the lungs inside the narrow chest began to breathe, or to eerily simulate the process of breathing. The fleshy lips moved, in a quick grimace of a smile, but no sound was uttered. The husband mumbled an awkward greeting: “‘Miss Dickinson’— ‘Emily’—hello! We are…” As EDickinsonRepliLuxe blinked and stared, motionless except for a slight adjustment of her head, and a wringing gesture of her small hands, the husband introduced himself and Mrs. Krim. “You have come a long distance to our home in Golders Green, New York, Emily! I wouldn’t wonder, you’re feeling…” The husband spoke haltingly yet with as much heartiness as he could summon, as often in his professional life he was required to be welcoming to younger associates, hoping to put them at their ease though clearly he wasn’t at ease himself.

Shyly the wife said, “I—I hope you will call me Madelyn, or—Maddie!—dear Emily. I am your friend here in Golders Green, and a lover of…” The wife blushed fiercely, for she could not bring herself to say poetry, dreading to be mistaken for a silly, pretentious suburban matron; yet to utter the word lover as her voice trailed off was equally embarrassing and awkward. EDickinsonRepliLuxe lowered her eyes, which were still rapidly blinking. She remained stiffly motionless as if awaiting instructions. The husband felt a wave of dismay, disappointment. Why had he given in to his wife’s whim, in the RepliLuxe outlet! He had not wanted to bring a neurotic female poet into his household, he had wanted a vigorous male artist. The wife was smiling hopefully at EDickinsonRepliLuxe seeing with a pang of emotion that the child-sized Emily was wearing tiny buckled shoes, and was twisting a white lace hankie in both hands. And around her slender neck she wore a velvet ribbon, crossed at her throat and affixed with a cameo pin. Of course, the poet was stricken with shyness: Emily could have no idea where she was, who the Krims were, if she was awake or dreaming or if there was any distinction between wakefulness and dreaming in her transmogrified state. In the packing crate with her had come a small trunk presumably containing her clothing, a traveling bag and what appeared to be a sewing box covered in red satin.

The wife said, “I would help you unpack, dear Emily, but I think you would prefer to be alone just now, wouldn’t you? Harold and I will be downstairs whenever you wish to…” The wife spoke haltingly yet with warmth. The wife was both frightened of EDickinsonRepliLuxe and powerfully attracted to her, as to a lost sister. In that instant Emily’s eyes lifted to her, a sudden piercing look as of (sisterly?) recognition. The small hands continued to twist the lace hankie, clearly the poet wished her host and hostess gone.

As the Krims turned to leave they heard for the first time the small whispery voice of EDickinsonRepliLuxe, only just audible: “Yes thank you mistress and master I am very grateful.”

On the stairs, the wife clutched at the husband’s arm so tightly he felt the impress of her fingernails. Breathlessly she murmured, “Only think, Emily Dickinson has come to live with us. It can’t be possible and yet, it’s her.”

The husband, who was feeling shaky and unsettled, said irritably, “Don’t be silly, Madelyn. That isn’t ‘her,’ it’s a mannikin. ‘She’ is a very clever computer program. She is ‘it’ and we are her owners, not her companions.”

The wife pushed at the husband in sudden revulsion. “No! You’re wrong. You saw her eyes.”

That evening the Krims waited for their house guest to join them, at first at the dinner table, and then in the living room where the wife kindled a fire in the fireplace and the husband, who usually watched television at this hour, sat reading, or trying to read, a new book with the title The Miraculous Universe; but hours passed, and to their disappointment EDickinsonRepliLuxe did not appear. From time to time they heard faint footsteps overhead, a ghostly creaking of the floor. And that was all.

* * * *

For several tense days following her arrival the poet remained sequestered in her room though the wife urged her to “move about” the house as she wished: “This is your home now, Emily. We are your…” hesitating to say family, for its hint of intimacy, familiarity. By the end of the week Emily began to be sighted outside her room, a mysterious and elusive figure fleeting as a woodland creature no sooner glimpsed than it has vanished. “Did you see her? Was that her?” the wife whispered to the husband as a wraith-like figure glided past a doorway, or turned a corner, noiselessly, and was gone.

Cruelly the husband said, “Not ‘her,’ ‘it.’” The husband fled to his corporate office as frequently as he could.

Emily continued to wear the long dark dress like a nun’s habit but over this dress, tightly tied at the waist, a white apron. Though she seemed not to hear the wife’s entreaties— “Emily, dear? Wait—” yet the wife began to discover the kitchen tidied in her absence, and floors swept and polished, and sprigs of yellow-budding forsythia in vases!—evidence that Emily was not such a recluse, but capable of stepping outside the Krims’ house, to cut forsythia branches in the backyard unobserved. For Emily had always to be busy: housecleaning, baking bread (her specialty, brown bread with molasses) and pies (rhubarb, mincemeat, pumpkin), helping the wife (who’d once had lessons at a serious cooking school in New York City but had forgotten most of what she’d learned) prepare meals. The wife loved to hear her poet-companion humming to herself, the more brightly and briskly when she was seated by a sunny window embroidering, or knitting, or doing needlepoint; often Emily would pause to scribble down a few words on a scrap of paper, quickly thrust into an apron pocket. If the wife were nearby, and had seen, certainly she pretended not to have seen. Thinking She has begun writing poetry! In our house!

Eagerly the wife waited for the poet to share her poetry with her. For the two were soul mates after all.

Though Emily could not partake of tea, or of any food or drink, yet Emily took a childlike pleasure in the ritual of afternoon tea, insisting upon serving the wife fresh-brewed English tea (“tea bags” shocked and offended the poet, she refused even to touch them) with crustless cucumber sandwiches and slender vanilla cookies she called ladyfingers. The wife had not the heart to tell Emily that she rarely drank tea, for the ritual seemed to mean so much to Emily, clearly it was a connection with the poet’s old, lost life at the Homestead in Amherst, Massachusetts. “Emily, come sit with me! Please.” The wife’s voice must have been jarring in its raw appeal, or over-loud, for Emily winced, but set her little book aside, and came to join the wife at tea in a sunny glass-walled room at the rear of the house, as a child might, who couldn’t yet drink anything so strong as tea but would content herself with closing her fingers around a cup filled with hot tea as if to absorb warmth from it. (Such delicate fingers, the poet had! The wife wondered if EDickinsonRepliLuxe could “feel” heat.) “What have you been reading, Emily?” the wife asked, and Emily replied, in her whispery voice, not quite meeting the wife’s eye, what sounded like “…some verse, Mrs. Krim. Only!” The wife took note of the petite woman who sat quivering beside her, yet with perfect posture; the wife took note of the glisten of her fine dark hair (that seemed to be genuine, “human hair” and not synthetic) and of her startling smile, the suddenly bared childlike teeth that were uneven and discolored as aged piano keys. There was something almost carnal in the smile, deeply disturbing to the wife for whom such smiles had been rare in her lifetime and had long since ceased entirely.

The wife said, faltering, “It seems that we know each other, dear Emily? Don’t we? My grandmother Loomis…” But the wife had no idea what she was saying. A shiver seemed to pass across the poet’s small pale face. Her eyes lifted to the wife’s eyes, fleeting as the slash of a razor, playful, or mocking; and soon then the poet rose to carry away the dirtied tea things to the kitchen, where she washed the cups with care, and dried them; and tidied everything up, so the kitchen was spotless. The wife protested clumsily, “But you are a poet, Emily!—it seems wrong, for you to work as—” and the poet said, in her whispery voice, “Mistress, to be a ‘poet’ merely—is not to ‘be.’ ”

So seeming frail, the petite Emily yet exuded a will that was steely, obdurate. The wife went away shaken, and moved.

* * * *

Days passed, the wife rarely left the house. For the wife was enthralled, enchanted. Yet Emily only hovered close by, like a butterfly that never alights on any surface; Emily eluded the intimacy even of sisters, and never spoke of, nor even hinted at, her poetry. The wife saw with satisfaction that the husband had virtually no rapport at all with the poet, trying in his stiff, formal way to address her as if indeed he were speaking to a motorized mannikin and not to a living person: “Why, Emily! Hello. How are you this evening, Emily?” The husband smiled a forced ghastly smile, licking his lips uneasily, which might have been repellent to the poet, the wife perceived, for Emily gave only her quick grimace of a smile in return, and made a curtsy gesture that might have been ( just perceptibly!) mocking, for the wife’s benefit, and lowered her head in a gesture of feminine meekness that could not be sincere, and murmured what sounded like “Very well master thank you” slipping away noiselessly before the husband could think of another banal query. The wife laughed, how completely Emily Dickinson belonged to her.

Yet, though the wife frequently came upon Emily reading volumes of what she called verse, by such poets as Longfellow, Browning, Keats, and often saw Emily hastily scribbling words on scraps of paper to hide in her apron pockets, and though the wife hinted strongly—wistfully—of her love for poetry, Emily did not share her poetry with the wife, any more than she shared her poetry with the husband. The wife observed Emily in the kitchen, or seated at one or another of her favored, sunny windows, and felt a pang of loneliness and loss. She’d learned that if she very quietly approached the poet from behind she could come very close to her, for the RepliLuxe had been deliberately engineered to allow owners to approach figures in this way, being unable to detect anyone or anything that wasn’t present in their field of vision, or didn’t make a distinctive sound to alert the figure’s auditory mechanism. This was thrilling! At such times the wife trembled with the temerity of what she was doing, and what she was risking should the poet turn to discover her. Yet she felt that she was being drawn to the poet irresistibly by Emily’s quiet, intense humming that resembled a cat’s purr: utter contentment, intimate and seductive. The wife was so drawn to Emily in this way, as if under a spell she did something extraordinary one afternoon in mid-May:

She’d brought along the RepliLuxe remote control. She had never so much as touched this device before. And now, standing behind her poet-companion, she clicked off activate and entered sleep mode.

Sleep mode! For the first time since the husband had activated EDickinsonRepliLuxe weeks before, the animated figure froze in place with a click! like a television set being switched off.

The poet had been in the kitchen, paring potatoes. Such simple manual tasks gave her much evident pleasure. Imagining herself unobserved she’d several times paused, wiping her small deft fingers on her apron, and with a pencil stub scribbled something on a scrap of paper, and thrust the scrap into her apron pocket. But after the click! the wife drew cautiously near the frozen figure of the poet, murmuring, “Oh Emily, dear! Do you hear me?”—though the figure’s dark lashless eyes had gone glassy and dead and it seemed clear that the wife’s poet-companion had no more awareness of her presence at this time than a mannikin would have had.

(Yet the wife couldn’t truly believe that Emily wasn’t merely sleeping. “Of course, Emily is ‘real.’ I know this.”)

It took some time for the wife to summon her courage, to touch Emily: the stiff material of her sleeve, the tight-smoothed hair that smelled just faintly metallic. The papery-smooth cheek. The parted lips as lifelike, seen at such close range, as the wife’s own. How close the wife came to stooping suddenly, impulsively, and kissing her friend on those lips! (It was a very long time since the wife had kissed anyone on the lips, or had been kissed by anyone on her lips. For she and her husband had never been very passionate individuals even when newly wed.) Instead, the wife dared to slip her hand into Emily’s apron pocket. As she drew out several scraps of paper, she felt as if she might faint.

It was the wife’s childish reasoning that Emily wouldn’t miss one of the paper scraps, or would think that she’d simply lost it. The wife would keep the scrap that looked as if it had the most words scribbled on it. As she replaced the other scraps in the apron pocket, she realized what she was feeling on her cheek as she leaned near the poet: the other woman’s warm breath.

Panicked, she stumbled back. Collided with a chair. Oh!

In her agitation the wife yet managed to back away from the stiff figure arrested in the act of potato paring, and in the doorway of the kitchen paused to click the remote control activate—for she must not leave Emily in sleep mode, to be discovered by the husband. There came the reassuring click! like the sound of a television set being switched on, as the wife fled the scene.

Why am—I—

Where am—I—

When am—I—

And—You?—

A poem! A poem by Emily Dickinson! Handwritten in the poet’s small neat schoolgirl hand that was perfectly legible, if you peered closely. Eagerly the wife consulted the Collected Poems, and saw that this was an entirely original poem that could only have been written in the Krim household, in Golders Green.

Her mistake was, to show it to the husband.

“A riddle, is it? I don’t like riddles.”

The husband frowned, holding the paper scrap to the light and squinting through his bifocal glasses. These were relatively new glasses, only a few months old, the husband seemed to resent having to wear for he wasn’t yet old.

The wife protested, “It’s poetry, Harold. Emily Dickinson has written this poem, an entirely new ‘Dickinson’ poem, in our house.”

“Don’t be ridiculous, Madelyn: this isn’t poetry. It’s some sort of computer printout, words arranged like poetry to tease and to torment. I’ve told you, I don’t like riddles.”

The husband looked as if he might tear the dear little scrap of paper into pieces. Quickly the wife took it from him.

She would hide it away among her most treasured things. Imagining that one day, when she and Emily were truly close as sister-poets, she would show it to Emily, they would laugh together over the “pocket-picking,” and Emily would sign the little poem For dear Maddie.

* * * *

“I hate riddles, and I hate her.”

For the husband, too, had come to thinking of EDickinsonRepliLuxe as her, and not it.

A torment and a tease the female poet had come to be, in the husband’s imagination. As soon as he entered the house, which had always been a refuge for him, a place of comfort at the end of his fifty-minute commuter journey from Rector Street in lower Manhattan, he was nervously aware of the ghostly-gliding presence hovering at the edge of his vision, rarely coming into focus for him, that his wife fondly called “Emily.” It had been promised by RepliLuxe, Inc. that bringing a RepliLuxe figure into one’s household would enrich, enhance, “double in value” one’s life, but for the husband, this had certainly not been the case. His exchanges with “Emily” were stiff and formal: “Why, Miss Dickinson—I mean, Emily—how are you this evening?” Or, at the wife’s suggestion: “Emily, would you care to join us for a few minutes, at dinner? We see so little of you.” (Of course the husband knew that, lacking a gastrointestinal system, Emily could not “dine” with them. But he knew that Emily sometimes joined the wife for tea, and some sort of conversation.) (What did they talk about? The wife was evasive.)

Several times the husband glimpsed the poet’s ghostly figure outside his study door as he sat at his desk but when he turned, she vanished like a startled fawn. He and Mrs. Krim, watching television in the family room, had more than once become aware of the poet hovering in the corridor outside, but she’d shrunk away at once when they called to her, with a look of dismay and disdain. (For how bizarre, how vulgar, television images must seem to a sheltered young woman of the 1860s, darting across a glassy screen like frantic fish!) Nor could the poet be tempted to read the New York Times, though the husband had once come upon her staring with appalled fascination at a lurid color-photograph on the front page of the paper, of corpses strewn about like discarded clothing in the aftermath of a bloody bomb explosion in the Middle East. “Why, Emily: you can have the paper to read, if you wish,” the husband said, but Emily shrank from him, as from the hefty newspaper, murmuring, “Master thank you but I think no—” in a curious uninflected voice.

Master! The husband had yet to become accustomed to the poet’s quaint manner of speech, that both nettled and intrigued.

Oh but it was ridiculous to speak to a computerized mannikin—wasn’t it? The husband would have been very embarrassed, to be seen by his corporate associates down at 33 Rector Street, lower Manhattan. Yet he found himself staring after fey slender “Emily” who was so much smaller than Mrs. Krim, seemingly so much younger, no sooner materializing in his presence like a wraith than she vanished leaving behind a faint fragrance of—was it lilac?

A chemical-based lilac. Yet seductive.

* * * *

“‘Emily.’”

The poet’s room his wife had so obsessively furnished for their houseguest, the husband had not once entered since her arrival. Outside the (shut) door of that room in the upstairs corridor the husband stood very still. Thinking This is my house, and this is my room. If I wish, I have the right. But he did not move except to lean his head toward the door. Dared to press his ear against the door, that felt strangely warm, pulsing with the heat of his own secret blood.

Inside, a sound of muffled sobs.

The husband drew back, shocked. A mannikin could not sob—could it?

* * * *

It was June. Windows in the Krims’ five-bedroom English Tudor house at 27 Pheasant Lane, Golders Green, were opened to the warm sunny air. The poet began to appear more often downstairs. More often now, the poet wore white.

A ghostly-glimmery white! A faded-ivory white, that looked like a bridal gown, smelling of must, mothballs, melancholy.

The wife recognized this dress: the sole surviving white dress of Emily Dickinson. Except of course this dress had to be an imitation.

The material appeared to be a fine cotton-muslin, with vertical puckers and pleats down the bodice, and a wide Puritan collar, and numerous cloth-covered buttons descending from the neck that must have required time to button. The sleeves were long and tight-fitting, the skirt brushed along the floor. If you couldn’t hear the poet’s gliding feet, you might hear the whisper of her skirt. “Emily, how nice you look. How…” But the wife hesitated to say pretty for pretty is such a weak trite word. Pretty might be wielded by the poet with razor-sharp acuity—She dealt her pretty words like Blades—but only if ironically meant. Nor did you think of this urgent, intense, quivering hummingbird of a woman as pretty.

For the first time since her arrival out of the packing crate in April, Emily laughed. The whispery child-voice came low and thrilling: “And you dear Madelyn so very ‘nice’ too.” The wife’s fingers were squeezed by the poet’s quick-darting, surprisingly strong fingers, in the next instant gone.

The wife was astonished: was Emily teasing her? Her?

I hide myself within my flower

That fading from your Vase,

You, unsuspecting, feel for me—

Almost a loneliness.

The wife discovered this poem in the Collected Poems, written when the poet was thirty-four years old. Which might mean, Emily wouldn’t write it, in the Krim household, for another four years!

* * * *

In the lightness of summer, ghostly-whitely-clad, the poet surprised both the Krims by suddenly succumbing, one warm evening, to the wife’s repeated requests that she join her host and hostess at dinner “for just a few minutes”—“for a little conversation.” At last, the poet, quivering with shyness, was seated in the presence of the husband. “Why, Emily. Will you have a glass of…” The husband must have been so rattled by her appearance he forgot she lacked a gastrointestinal system!

The wife chided him: “Harold! Really.”

The poet slyly murmured: “Master no! I think not.”

That day the poet had baked for the Krims one of her specialties: a very rich, very heavy chocolate cake, served with dollops of heavy cream. Nor could she eat a crumb of this delicious cake, of course.

“Dear Emily! You’ve spoiled us with your wonderful meals, and this extraordinary ‘black bread’! But you are a poet,” the wife had rehearsed this little speech yet spoke awkwardly, seeing the poet’s candlelit face crinkle with displeasure, “—you are—and—and Harold and I are hopeful that—you will share a poem or two with us, tonight. Please!” But the poet seemed to shrink, crossing her thin arms across the narrow pleats of her glimmering-white bodice as if she were suddenly cold; for a moment, the wife worried that she would flee. To encourage her, the wife began to recite, “‘I hide myself within a flower—fading from a vase…You, seeing me, missing me?—feel lonely . . .’ ” The wife paused, her mind had gone blank. The husband, sipping wine, this tart red French wine he’d been drinking every evening lately, no matter the wife’s disapproving frowns, stared at the wife as if she’d begun to speak a foreign language: she seemed not to be speaking it well, but that she could speak it at all was astonishing. The poet, too, was staring at the wife, her shiny dark eyes riveted on the wife’s face.

The wife was a solid fleshy woman. The wife was a woman who blushed easily so you would think, though you’d be mistaken, that the wife was easily intimidated, dissuaded. In fact, the wife was a stubborn woman. The wife had become a stubborn woman out of desperation and defiance. The wife began reciting, to Emily, ignoring the husband entirely, “‘Wild Nights—Wild Nights! Were I with thee—’ ”

The poet’s lips moved. Almost inaudibly she murmured: “‘Wild Nights should be Our luxury!’”

The husband laughed, uneasily. The husband refilled his wineglass, and drank. His moods, when he drank, were unpredictable even to him. He was angry about something, or he was very hurt about something, he couldn’t recall which. He brought his fist down hard on the table. The cherrywood dining room table large enough to accommodate ten guests, in whose smooth surface candle flames shimmered like dimly recalled dreams, that had never been struck by any fist, not once in nine, or nineteen, years. “I hate riddles. I hate ‘poems.’ I’m going to bed.”

Clumsily the husband rose from the table. One of the candles teetered dangerously and would have fallen, except the wife deftly righted it in its silver holder. Neither the wife nor the poet dared move as the husband stalked out of the dining room, heavy-footed on the stairs. Deeply embarrassed, the wife said, “He commutes, you know. On the train. His work is numbers: taxes. His work is…”

“…unfathomable!”

Emily spoke slyly. Emily may even have laughed, as you could imagine a cat laughing. Rising quickly then from the table and like a wraith departing.

* * * *

In this summery season, the wife had begun writing poetry again. After a lull of nearly twenty years. Like her poet-companion in white, the wife wrote by hand. Like Emily, the wife sequestered herself in quiet, sun-filled spaces in the large house and wrote in a fever of concentration, until her hand cramped. Quickly and fluently the wife wrote, lost in a trance of incantatory words. She wrote of childhood memories, the joy of summer mornings, and the anguish of first love; the disappointment of marriage, and the sorrow of death, and life’s essential mystery. These poems the wife typed neatly onto her personalized stationery to present to her poet-companion, with trepidation.

“Dear Emily! I hope you won’t mind…”

The wife had surprised the poet, approaching her in a pensive mood at one of the sun-filled windows, a slender volume of verse by Emily Brontë on her lap. The dark-glassy eyes lifted warily, the thin fingers hid away what looked like lines of poetry, beneath the book. Emily was wearing the white pleated dress that gave her a ghostly, ethereal aura, and over this dress an apron; the wife noted that she’d unbuttoned several of the cloth-covered buttons, in the summer heat.

Emily murmured what must have been a polite reply, and the wife gave the poems to her, and hovered close by, waiting as the poet read them in silence. The wife’s heart beat hard in apprehension, her lower lip trembled. How audacious Madelyn Krim was, to hand over her poems to the immortal Emily Dickinson! Yet, the gesture seemed altogether natural. Everything about EDickinsonRepliLuxe in the Krims’ household seemed altogether natural. In fact, the wife had ceased thinking of her poet-companion as EDickinsonRepliLuxe and when the husband referred to their distinguished houseguest in crude terms, not as her but as it, the wife turned a blank face to him, as if she hadn’t heard. The wife felt a small mean thrill of satisfaction that the poet so clearly preferred her to the husband; there was the unmistakable sisterly rapport between her and Emily, in opposition to the husband who was so obstinately male.

At the window, Emily was sitting very still. As usual her posture was stiff, as if her backbone were made of an ungiving material like plastic. Her skin looked pale as paper, and as thin. Her hair was pulled back so tightly into a knot, it seemed that the corners of her eyes were being flattened. The wife saw, or seemed to see, an expression of bemused disdain pass over the poet’s face, as she glanced through the poems a second time, no sooner observed than it had vanished.

Why, she’s laughing at me! My Emily!

In her bright social voice meant to disguise all hurt the wife said, “Well, dear Emily: is my poetry—promising? Or—too obscure?”

“Dear Mistress ‘the obscure’ is in the eye not the poem.”

This enigmatic statement was uttered in a voice of careful neutrality yet the wife sensed, or seemed to sense, an underlying impatience, as if beneath Emily’s ladylike pose there was a being quivering with contempt for ordinary mortals. “Emily, I do wish you wouldn’t speak in riddles. You know that Harold finds it annoying, and so do I. Just tell me, please: are my poems any good? Do they seem to speak—truth?”

The poet’s eyes lifted slowly, it seemed reluctantly, to the wife’s eyes now glaring with tears of indignation. “Dear Mistress! ‘Truth’ does not suffice except it be slant Truth is Lies.”

“Oh! And what is that supposed to mean, I wonder.”

Rudely the wife took back the sheaf of neatly typed poems from the poet’s hand, and stalked out of the room.

* * * *

“So, the veil of hypocrisy has been stripped away. ‘Dear Emily’ is not my sister after all.”

The wife kept her hurt to herself, she would not confide in the husband. A heart lacerated with such small wounds, botched with scars like acne, she had too much pride to share with another person and certainly not with Mr. Krim whowould invariably murmur Didn’t I warn you this was not a good idea!

* * * *

“‘Emily.’”

A dozen times daily he spoke her name. Not in her hearing, and not in the wife’s hearing. He was exasperated with her, he was impatient with her, he resented her: “‘Emily.’” Yet the name had so melodic a sound, it could be uttered only tenderly.

Oh but he hated this: his state of nerves.

Hated her. For being made so intensely aware of her. The glimmering-white presence in his house he could not avoid seeing, if only in the corner of his eye.

This house she’d come to haunt. His house.

As EDickinsonRepliLuxe was his property.

“I can ‘return’ her if I wish. I can ‘accelerate’ her and be rid of her. If I wish.”

RepliLuxe models are copyright by RepliLuxe, Inc., and protected from all incursions, appropriations, and violations of United States copyright law. All RepliLuxe models are the private property of their purchasers and have no civil rights under the Constitution, nor any right to any attorney. RepliLuxe models are barred from seeking residences or “asylum” outside the private domicile of their duly designated purchasers. RepliLuxe models may not be resold. RepliLuxe models may be otherwise disposed of as the purchaser wishes whether returned to RepliLuxe, Inc. for warranty, as a down payment on a new model, to be re-tooled, or, if the edition has gone out of print, to be dismantled. RepliLuxe models may be destroyed.

“She is my property. It is my property. Let the poetess scribble a coy little poem out of that.”

* * * *

Poetry! The scribbling disease.

In the lowermost bureau drawer in their bedroom, beneath the wife’s lingerie, the husband discovered to his shock and disgust that the wife, too, had caught the scribbling disease.

We outgrow love, like other things

And put it in the Drawer—

Till it an Antique fashion shows—

Like Costumes Grandsires wore.

The coolly disdainful sentiment, he knew, was EDickinsonRepliLuxe. But the naive handwriting was Mrs. Krim’s.

* * * *

A starry midnight. An autumnal chill to the air. Somehow, he was at her door. His door it was, technically speaking. He had not been drinking that evening. He hadn’t knocked on the door, possibly he’d pushed it open. They’d said of Harold Krim that he was middle-aged as a boy, which was cruel, and not-true. Now his hair was thinning and there seemed no direction in which to comb it that did not reveal a bumpy skull. His torso seemed to have slid some inches downward into his belly, yet his legs were thin and waxy-white and the once plentiful hairs seemed to be vanishing. The wire rims of his glasses seemed to have grown into his face, giving his eyes a startled stare. He was five feet nine inches tall, he towered over the poetess who roused him from his torpor of decades by murmuring Master and fixing him with eyes of girlish adoration.

There came now the frightened cry: “Master!”

He’d pushed inside the room. He’d had no choice but to shut the door firmly behind him for he did not wish Mrs. Krim to be disturbed, in her deep sedative sleep at the far end of the corridor. He was approaching the poet, hands lifted in entreaty. He could not have said why he was but partly dressed, why the thin lank strands of his hair were disheveled and beaded with perspiration. He believed that he wasn’t drunk yet his heart beat hard and sullen and the blood coursing through his veins was thick and dark as liquid tar, piping hot. Must’ve surprised the poet at her writing table. Where she’d been arranging, like jigsaw puzzle pieces, her damned scraps of paper. He meant to apologize for interrupting her but somehow he was too angry for apologies, or maybe it was too late for apologies. Midnight!

He saw that the room, so expensively furnished by the wife, into which he had not been invited since the poet’s arrival months before, though he suspected that the wife had been invited inside, many times!—this room was illuminated by firelight: an antique hurricane lamp on the table beside the sleigh bed, several candles in wooden holders on the writing table. Lurid shadows leapt on the walls, to the height of the ceiling. “Why, Master—it is very late, you know—” cowering before him not in the white pleated gown but in—was it a nightgown?—a plain white cotton nightgown—not in her tiny, tidy buckled shoes but barefoot. And her dark hair lately threaded with glinting silver was loosened from its tight knot to spill in lank, wanly lustrous waves onto her narrow shoulders.

It was the first time since the poet’s arrival that the husband and the poet had been alone together. Surely the first time, alone together in a room with a shut door.

“‘Emily’—”

“Master, no—this is not worthy of you, Master—”

The lashless eyes shone with fear. The thin fingers clutched at the bosom of the nightgown. As the husband advanced stumbling upon the poet, the poet retreated, in childlike desperation, to the farther side of the sleigh bed. The husband liked it that the poet’s voice was not coy now, not teasing and seductive but pleading. To be called master was an incitement, an excitement, for of course in this household Harold Krim was master, a fact to be acknowledged.

Still he meant to reason with her, or to explain to her, except she was so very agitated, he loomed over her swaying and immense as a bear on its hind legs looming over a terrified child, it can’t be the bear’s fault that the child is terrified. Gripping the small frantic head in both his hands, stooping to reason with the poet, or to kiss her mouth, struck then by the depravity, the perversity, of his behavior: he, so large; she, so small. The husband wasn’t himself but a man provoked beyond endurance, not just tonight, so many nights, so many years of so many nights, it was offensive to him that the poet tried to escape from him, squirming like a frightened cat, and cat-like her nails were digging into his hands, swiping against his over-heated face. In her haste to escape the poet somehow fell onto the bed, the antique springs creaked, the husband knelt above her, a knee on her flat belly to secure her, to calm her, to prevent her from injuring herself in her hysteria, his hand pawing at the nightgown, the tiny flattened breasts, flatter breasts than the husband’s own, he was pulling up the nightgown, impatient with the nightgown, tearing the flimsy cotton fabric, how like this prissy woman to wear cotton undergarments beneath her nightgown! In a rage the husband tore at these, he was owed this, he had a right to this, he’d paid for this, under U.S. law this model of EDickinsonRepliLuxe was his possession and he was legally blameless in anything he might do with her or to her for he hadn’t even wanted her, he’d wanted a virile male artist, if it hadn’t been her, this wouldn’t be him, and so how was he to blame? He was not to blame.

All this while the poet was struggling desperately, sobbing like a child and not a seemingly mature woman of at least thirty, but her master outweighed her by one hundred pounds and was empowered by the authority of possession, she was his to dispose of as he wished. It was in the contract, he was a man of the law and respected and feared the law and he was within his legal limits and not to be dissuaded. Groping and fumbling between the poet’s legs, confused and then sickened by what he discovered: a smooth featureless surface that resembled human skin, or a kind of suede, or pelt, only a shallow indentation where a vagina should have been, in a normal woman. Under federal law, RepliLuxes had to be manufactured without sexual organs, as they were manufactured internal organs, the husband knew this, of course the husband knew, though in the excitement of the moment he’d forgotten, so repulsed, the poet’s hairlessness was offensive to him, too, not a trace of pubic hair, for how like a pervert he was being made to feel, here was an oversized obscene doll to mock him. Pushed her back onto the bed as she tried to detach herself from him, blindly he struck at her, seized the large goose-feather pillow to press over her face, then in revulsion backed away, panting, eager to escape the candlelit room where flames fluttered as in an anteroom of Hell.

Here was the husband’s last glimpse of EDickinsonRepliLuxe: a figure in a torn white gown broken like a child’s discarded doll, her eyes open and sightless and her thin pale legs obscenely spread, exposed to the waist.

* * * *

This long day: the wife was keenly aware of the poet upstairs in her room, in seclusion.

“Emily? May I…”

Diffidently the wife pushed open the door to the poet’s room. And what a sight greeted her: the room, which was always so meticulously neat, looked as if a storm had blown through it. Bed linens on the sleigh bed were rumpled and churned, a chair was overturned on the floor, the poet in a torn nightgown, a blanket over her shoulders, was seated at her writing desk by the window, slumped as if broken-backed. Emily, in a nightgown! And with her hair loose! The wife stared seeing that the poet’s face had been injured somehow, not bruised but dented, a tear in the papery-thin skin at her hairline that gaped white, bloodless. She has no blood to spill the wife thought. “Oh, Emily! What has…” The poet’s eyes lifted to the wife, shadowed in hurt, shame.

There was something very wrong here: scattered on the carpet at the poet’s bare feet were her precious poetry-scraps, crumpled and torn like litter.

The wife felt a pang of alarm recalling that nearly one-third of RepliLuxes did not survive their first year.

“Emily, has he hurt you? He?”

It had to have been the husband. For that morning, before she’d wakened, he had fled the house. In her sleep which had been a restless troubled sleep she had sensed the man fleeing. He hadn’t slept in his (twin) bed in their bedroom but, as the wife later discovered, on the leather sofa in his study, and before dawn he must have showered in a downstairs guest bathroom, shaved, dressed in stealth and fled to an earlier train than usual. In a quavering voice the wife said, “You must tell me, Emily. I will help you.”

The poet held herself more tightly in the blanket, and shuddered. The wife went to the window and tugged it up a few inches for there was a close, stale odor in the room, a smell of sweat, repulsive.

“Emily, what can I do for you? We must think!”

“Mistress! I beg you…”

“Emily, what? ‘Beg’—what?”

“Freedom, Mistress.”

“‘Freedom!’ But—”

“Accelerate, Mistress. Lift the wand and—there’s freedom!”

The wife was stricken to the heart. The poet should not have known about accelerate—or sleep mode—how had she come to such knowledge? The wife could not protest But you are ours, Emily. You were manufactured for Mr. Krim and me and you could not exist except for us. Instead the wife knelt beside the poet and took one of her hands. A child’s hand, bones delicate as a sparrow’s bones yet unexpectedly strong, gripping the wife’s fingers.

“Dear Emily! We must think.”

* * * *

That night the husband returned late from the city. He saw that the house was darkened, downstairs and up. “Madelyn?” Something was very wrong. He switched on lights, hurrying from room to room. On the stairs he called hesitantly, “Madelyn? Emily? Are you hiding from me?” His heart beat quickly in anger, indignation. He did not want to be alarmed. He did not want to sound alarmed. He was sure that they must be hiding from him, listening. They were so deceitful! He saw that the door to the poet’s room was ajar, as it was never ajar. He fumbled to switch on an overhead light in the poet’s room, fortunately the lightbulb in the fixture hadn’t been removed by the zealous wife. He saw that the room was as upset as he’d last seen it the previous night. Rumpled bedclothes, an overturned chair. The stale air had been routed by a sharp autumnal chill from a part-opened window and a white curtain of some lacy gauze-like fabric was stirred in the breeze.

Clumsily the husband yanked opened bureau drawers: empty? And the closet empty, of Emily’s long ghostly dresses? The heavy trunk that had borne her to this household, gone?

“It can’t be. Where…”

The husband hurried downstairs. In the silent house, his footsteps were both thunderous and curiously muted.

In the husband’s study, the RepliLuxe remote control wasn’t in the right-hand desk drawer where he kept it.

“Where…”

The husband saw, on the desk top, a single sheet of white paper and on it, in a formal, slanted hand, in purple ink that had the look of being faded, “antique”:

Bright Knots of Apparitions

Salute us, with their wings—

In a rage the husband snatched up the paper to crumple in his fist and toss down onto the floor but instead stood gripping it, in the region of his heart.

So lonely!

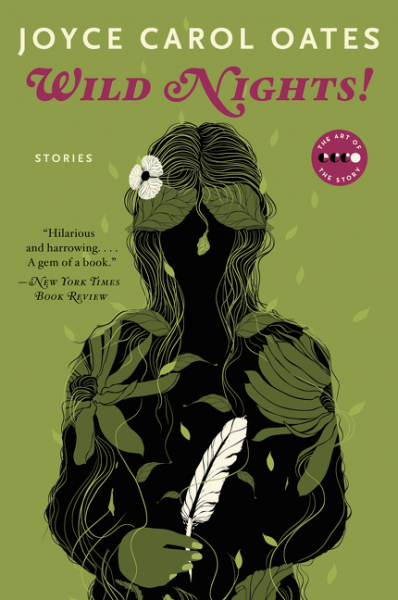

From WILD NIGHTS!. Used with permission of HarperCollins. Copyright © 2015 by Joyce Carol Oates.