The 28th issue of Kayak—a literary magazine edited and published by George Hitchcock out of Santa Cruz, California—appeared in 1972. The issue includes mostly poetry, as well as a few book reviews, a work of verse fiction, collages, illustrations lifted from old books and manuals, and an acerbic letter to the editor (“Kayak 27: Pretty bad.”).

“Ah, but everything is forgotten, almost everything,?” Raymond Carver writes in one stanza, “and sooner rather than later, please God—.” Diane Wakoski invokes her poem “Transformations,” “for all the imaginary men”: “there are many men / with wide shoulders / and the hands of carpenters.” Philip Levine ends his poem:

Dawn scratching at the windows

Counted and closed

The doors holding

The house quiet

The kitchen bites its tongue

And makes bread.

Charles Simic, in the final poem of the issue, writes: “I had first to be born / On the quivering tail of the planet, dip / My tongue in different sugar.” The issue is an uneven bounty, a reflecting product of its time.

To the uninitiated, literary magazines might appear strange, frenetic, provincial. That’s exactly why they are wonderful.

The first literary magazine I ever encountered was my high school’s publication, Etcetera. I wasn’t on staff, but I had a story in an issue: a maudlin vampire story that I wrote and revised each night after basketball practice. Eons later, I now advise the literary magazine at the high school where I teach English.

Where else but a literary magazine can you find gentle former poet laureate Ted Kooser being pugilistic…I’m the culture editor for Image Journal, a print quarterly out of Seattle. My writing has appeared in “America’s oldest continuously published literary quarterly” (The Sewanee Review), some august ones (Kenyon Review, Iowa Review, Shenandoah), some with memorable names and revelatory words (Caketrain, Annalemma). Old rejection slips and cards fill a desk drawer—they carry a bit more emotional weight than digital dismissals. Back issues of magazines line bookshelves in my house and in my classroom, and offer a diverse collection of reading within each edition.

In short, I love literary magazines. They often feel like literature at its purest: the ardent hope that a few people—on a tight or nonexistent budget—can cultivate a literary community, one that is beautifully egalitarian: established writers can appear in the same issue as writers who have never published before. I love books, but there’s something special about these occasional literary missives: they offer an introduction (or a reunion) with so many voices at once.

Literary magazines are eclectic, refreshingly wild, and important. In that spirit, this new regular column will meander through the back issues of various literary magazines—some long gone, some as yet unknown, some alive and well. I’ll feature three issues per column, hoping to showcase the great work there—and hopefully inspire you to forage through the pages yourself.

*

Poems—those oddly beautiful offerings of love, lust, confusion, faith—were made for the lithe pages of lit mags.

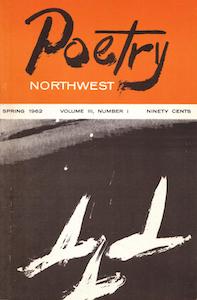

The Spring 1962 issue of Poetry Northwest—with a cover by artist Mark Tobey—includes three poems by W.S. Merwin, each inspired or derived from elsewhere: a Greek ballad, the Spanish of Fr. Ángel María Garibay Kintana, the French of Joachim du Bellay. In the first poem, “Song of Exile,” Merwin writes “I will become / Earth so that you can walk on me, / A bridge so that you can cross.” In the final poem, “A Winnower of Wheat, to the Wind,” the Hopkinsesque speaker offers violets, lilies, roses to “Fan with your sweet breath / This plain, / This place.”

Later in the issue appears the first English translations of Venezuelan poet, Rafael Pineda—from his Poemas para recordar a Venezuela; Pineda said the country “nurtured me with myths,” and he imbued “both the gentle and terrible ones” into his work. Translated by Keith Ellis, one poem unfolds as a dramatic origin myth:

I found that the world spun

around infinity,

because my mother

took equinoctial strolls in the yard.

My nakedness formed part of those very acts,

with fragile bones,

and flesh kneeling,

as if begging for pity in advance.

Pineda’s verses nicely complement a work by Brother Antoninus—poet William Everson’s devotional turn as a lay Dominican brother. He begins with an epigraph from the apocryphal Gospel of Thomas, and writes of violence and wonder: “In the clicking teeth of otters / Over and over He dies and is born, / Shaping the weasel’s jaw in His leap / And the staggering rush of the bass.” His booming verse contrasts two rollicking poems by Patricia Goedicke:

My crow condescends

But I shiver and shiver

Longing to share a feather,

To be framed, to flock

Together into the nest.

Yet ugly as sin,

Keeping my camera eye without,

Why should I be let in?

There’s a purity to a magazine that is unabashedly regional in some senses, and yet open to subjects and forms which transcend its place.

*

Poetry Northwest, as the name implies, is devoted to that mode exclusively—but I love when more general magazines devote special issues to poetry. Callaloo was founded in 1976 by Charles Rowell to consider the culture and literature of the Black South; the February 1979 issue was devoted to “Women Poets.” The cover is a detail from a 1952 mural by John Biggers, “Contributions of the Negro Woman to American Life and Education,” whose description of color in his work is itself lyric: “earth greens, grays, and browns, of the fields and shacks, the textures of burlap bags, faded blue overalls and feed sacks, and at times, the bright spots of gingham textiles and patched quilt work.”

Poetry Northwest, as the name implies, is devoted to that mode exclusively—but I love when more general magazines devote special issues to poetry. Callaloo was founded in 1976 by Charles Rowell to consider the culture and literature of the Black South; the February 1979 issue was devoted to “Women Poets.” The cover is a detail from a 1952 mural by John Biggers, “Contributions of the Negro Woman to American Life and Education,” whose description of color in his work is itself lyric: “earth greens, grays, and browns, of the fields and shacks, the textures of burlap bags, faded blue overalls and feed sacks, and at times, the bright spots of gingham textiles and patched quilt work.”

The issue teems with notable poets and quotable lines: Sonia Sanchez (“you, man, will you remember me when i die?”), Harryette Mullen (“the icewater click of windchimes tickled by a breeze / the shadows of leaves on a white adobe wall / a poem tacked up in the kitchen… i draw strength from these things, these magical symbols”), and June Jordan (“I / may stay in school or quit / and I say / it / don’ matter much”).

“Secret Seasons” by Jill Witherspoon Boyer builds toward a haunting stanza:

So now I plant in other worlds

and stand with the Balsam

against resolute winds

content to know

that not everything dies in winter

just as spring does not bring

all things back.

The final poem of nearly 150 pages of verse: the sharp “Revelation” by Sybil Dunbar: “never cried for any man / i’ve loved / i do cry for those women / whose fate it is / to love / them.”

*

The Mississippi Review devoted a special issue in 1991 to poetry, guest edited by Angela Ball and D.C. Berry. “The Burning Bush,” a poem by Tomaz Salamun translated from Slovene by Michael Biggins, ends:

There are hummingbirds at the Zocalo in Tlalpan,

and now I’ll come down off the bench, so I can

squat. Sometimes, if you suddenly squat

down, beauty emanates. It gives off a scent

like a juniper bush ablaze.

Why can’t the smell in the mirror be seen?”

Nancy Kricorian delivers a melancholy “Letter to James,” in which she thinks about her departed love—and how they used to have cereal for breakfast. “Some mornings the spoon / against your teeth bugs me,” she writes, “but / living with someone is like that.” There is nothing left to say, and the silence of the white space feels utterly final.

Although the issue is full of great poems, I’m most intrigued by its symposium—over 100 pages of poets responding to a question from the editors: “It has sometimes been said that contemporary poetry, however technically brilliant, lacks statement or vision. Please comment.” Where else but lit mags can such a conversation occur—and remain archived for enjoyment?

Some favorite responses: Reginald Gibbons (“I just don’t expect poetry and fiction ever to have a proper place in the academic world, because honesty requires us to admit that the two realms—art and academe—are antagonistic, and continue to fight the ancient battle between poetry and philosophy.”), Jane Hirshfield (“There may be, on any given evening in this country, something between five hundred and five thousand people who are making a serious attempt to write well the truth of their experience. Failure in this attempt is not without honor.”), and Cleopatra Mathis (“Motherhood in general is new to poetry. For women writers, it can fight and terrify; it splits the writer down the middle of her creative self.”).

Where else but a literary magazine can you find gentle former poet laureate Ted Kooser being pugilistic: “some of those poets who have recently returned to fixed forms in an attempt, perhaps, to capture some lost brilliance, are writing some of the deadest, dreariest, dullest poetry I have seen in years.”