Dorothy Parker on the Art of Her Old Pal James Thurber

"A Thurber must be seen to be believed—there is no use trying to tell the plot of it."

The following originally appeared as the introduction to James Thurber’s 1932 book The Seal in the Bedroom and Other Predicaments.

*

Once a friend of a friend of mine was riding a London bus. At her stop she came down the stair just behind two ladies who, even during descent, were deep in conversation; surely only the discussion of the shortcomings of a common acquaintance could have held them so absorbed. She heeded their voices but none of their words, until the lady in advance stopped on a step, turned, and declaimed in melodious British: “Mad, I don’t say. Queer, I grant you. Many’s the time I’ve seen her nude at the piano.”

It has been, says this friend of my friend’s, the regret of her days that she did not hear what led up to that strange fragment of biography. But there I stray from her. It is infinitely provocative, I think, to be given only the climax; infinitely beguiling to wander back from it along the dappled paths of fancy. The words of that lady of the bus have all the challenge of a Thurber drawing—indeed, I am practically convinced that she herself was a Thurber drawing. No one but Mr. Thurber could have thought of her.

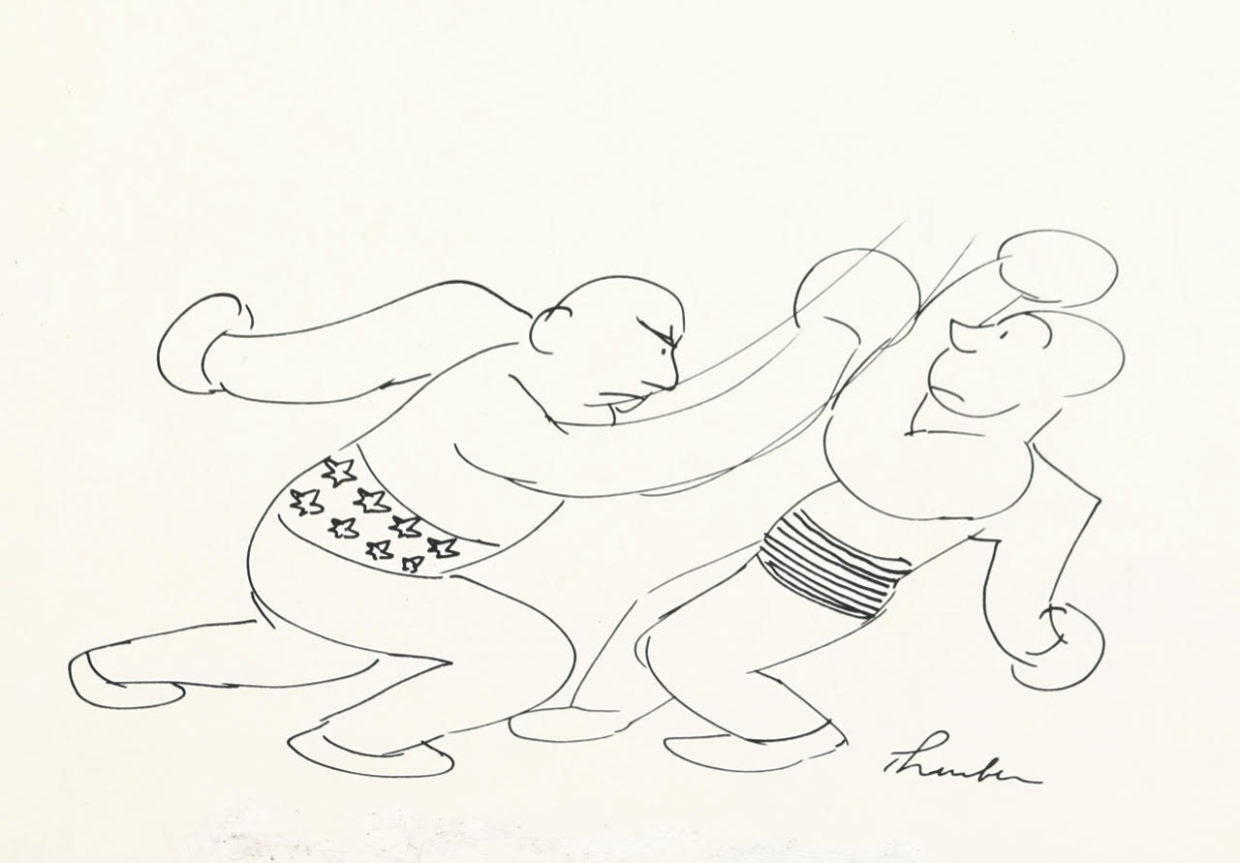

Thurber’s two boxers in a clinch led the “Goings on About Town” section of The New Yorker, June 22, 1940.

Thurber’s two boxers in a clinch led the “Goings on About Town” section of The New Yorker, June 22, 1940.

Mr. James Thurber, our hero, deals solely in culminations. Beneath his pictures he sets only the final line. You may figure for yourself, and good luck to you, what under heaven could have gone before, that his somber citizens find themselves in such remarkable situations. It is yours to ponder how penguins get into drawing-rooms and seals into bedchambers, for Mr. Thurber will only show them to you some little time after they have arrived there.

Superbly he slaps aside preliminaries. He gives you a glimpse of the startling present and lets you go construct the astounding past. And if, somewhere in that process, you part with a certain amount of sanity, doubtless you are better off without it. There is too much sense in this world, anyway.

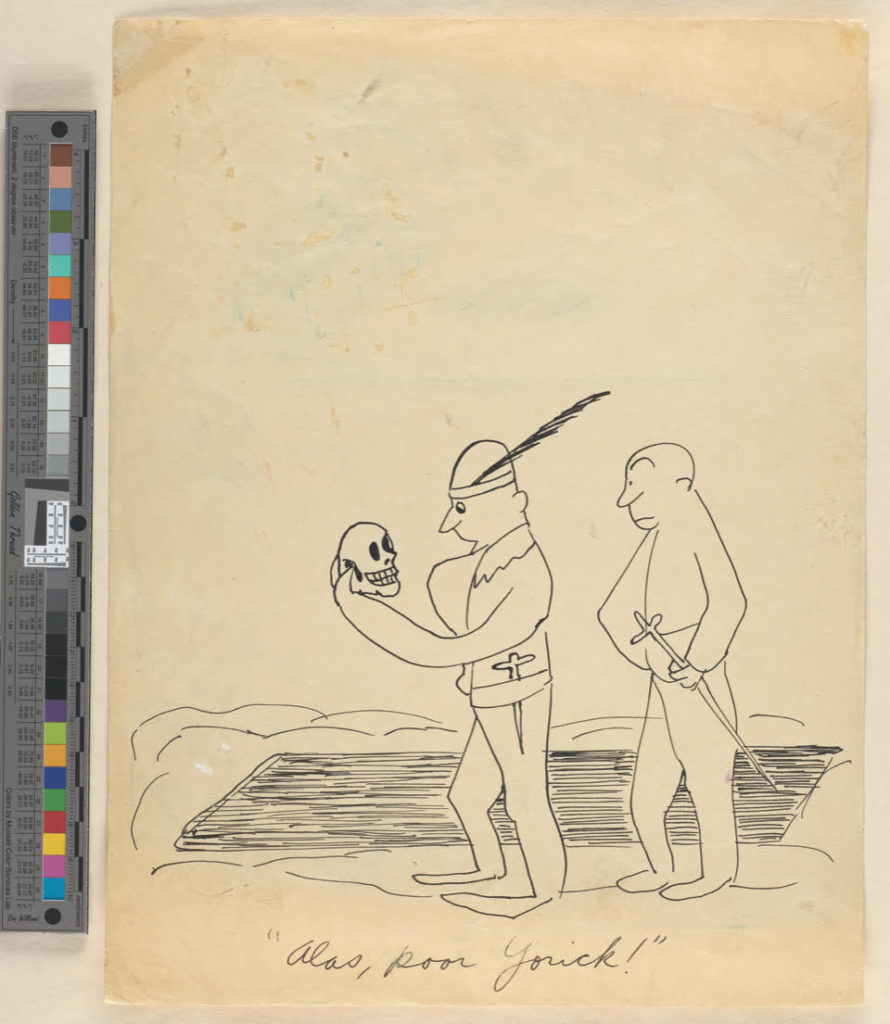

“Alas poor Yorick!” from “The James Thurber Production of Macbeth,” Stage, November 1935.

“Alas poor Yorick!” from “The James Thurber Production of Macbeth,” Stage, November 1935.

These are strange people that Mr. Thurber has turned loose upon us. They seem to fall into three classes—the playful, the defeated, and the ferocious. All of them have the outer semblance of unbaked cookies; the women are of a dowdiness so overwhelming that it becomes tremendous style. Once a heckler, who should have been immediately put out, complained that the Thurber women have no sex appeal. The artist was no more than reproachful. “They have for my men,” he said. And certainly the Thurber men, those deplorably désoigné Thurber men, would ask no better.

There is about all these characters, even the angry ones, a touching quality. They expect so little of life; they remember the old discouragements and await the new. They are not shrewd people, nor even bright, and we must all be very patient with them. Lambs in a world of wolves, they are, and there is on them a protracted innocence. One sees them daily, come alive from the pages of the New Yorker—sees them in trains and ferryboats and station waiting-rooms and all the big, sad places where a face is once beheld, never to be seen again.

“Dogs are now saying ‘scarf’ when they bark. They are envious of the ‘Thurber dogs’ which appear, in familiar moods and poses, on beautiful 18 in. scarves.”

“Dogs are now saying ‘scarf’ when they bark. They are envious of the ‘Thurber dogs’ which appear, in familiar moods and poses, on beautiful 18 in. scarves.”

It is curious, perhaps terrible, how Mr. Thurber has influenced the American face and physique, and some day he will surely answer for it. People didn’t go about looking like that before he started drawing. But now there are more and more of them doing it, all the time. Presently, it may be, we shall become a nation of Thurber drawings, and then the Japanese can come over and lick the tar out of us.

Mr. James Thurber, our hero, deals solely in culminations. Beneath his pictures he sets only the final line.

Of the birds and animals so bewilderingly woven into the lives of the Thurber people it is best to say but little. Those tender puppies, those fainthearted hounds—I think they are hounds—that despondent penguin—one goes all weak with sentiment. No man could have drawn, much less thought of, those creatures unless he felt really right about animals. One gathers that Mr. Thurber does, his art aside; he has 14 resident dogs and more are expected. Reason totters.

A crack-inspired mountain with hikers, donkey, clown, eagle, bear, and long-horned goat.

A crack-inspired mountain with hikers, donkey, clown, eagle, bear, and long-horned goat.

All of them, his birds and his beasts and his men and women, are actually dashed off by the artist. Ten minutes for a drawing he regards as drudgery. He draws with a pen, with no foundation of pencil, and so sure and great is his draughtsmanship that there is never a hesitating line, never a change. No one understands how he makes his boneless, loppy[sic] beings, with their shy kinship to the men and women of Picasso’s later drawings, so truly and gratifyingly decorative.

And no one, with the exception of God and possibly Mr. Thurber, knows from what dark breeding-ground come the artist’s ideas. Analysis promptly curls up; how is one to shadow the mental processes of a man who is impelled to depict a seal looking over the headboard of a bed occupied by a broken-spirited husband and a virago of a wife, and then to write below the scene the one line “All right, have it your way—you heard a seal bark”? . . . Mad, I don’t say. Genius, I grant you.

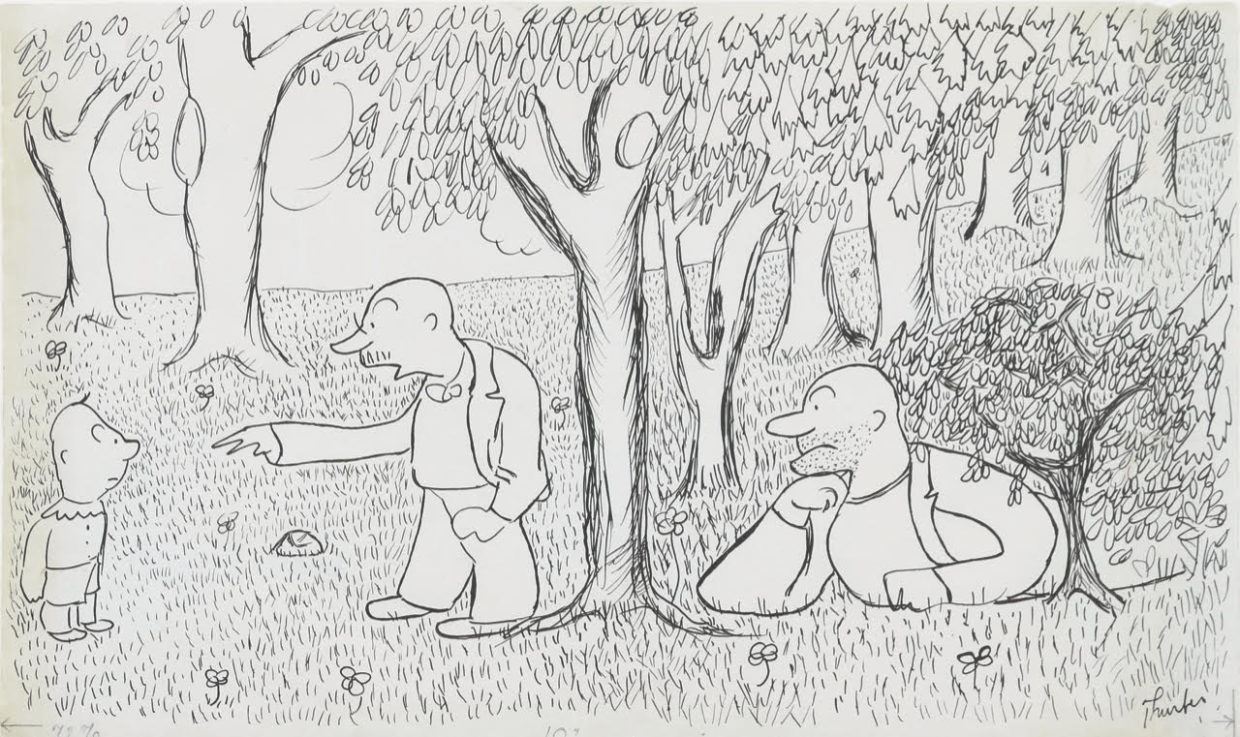

“No son of mine is going to stand there and tell me he’s scared of the woods.”

“No son of mine is going to stand there and tell me he’s scared of the woods.”

It is none too soon that Mr. Thurber’s drawings have been assembled in one space. Always one wants to show an understanding friend a conceit that the artist published in the New Yorker—let’s see, how many weeks ago was it? and always some other understanding friend has been there first and sneaked the back copies of the magazine home with him. And it is necessary really to show the picture.

A Thurber must be seen to be believed—there is no use trying to tell the plot of it. Only one thing is more hopeless than attempting to describe a Thurber drawing, and that is trying not to tell about it. So everything is going to be much better, I know, now that all the pictures are here together. Perhaps the one constructive thing in this year of hell is the publication of this collection.

And it is my pleasure and privilege—though also, I am afraid, my presumption —to introduce to you, now, one you know well already; one I revere as an artist and cleave to as a friend. Ladies and gentlemen—Mr. James Thurber.

________________________________________

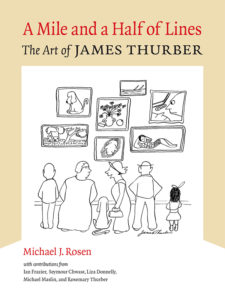

All works from A Mile and a Half of Lines: The Art of James Thurber, published by The Ohio State University Press, are copyright © 2019 by Rosemary A. Thurber. Reprinted by permission of Rosemary A. Thurber and the Barbara Hogenson Agency, Inc.

Dorothy Parker

Dorothy Parker was an American short story writer, poet, screenwriter and critic.