Depression as an acknowledged illness among children has a relatively short history. Often, with depression—especially among the young—symptoms are hard to pinpoint. They remain hidden and unobserved, concealed beneath the child’s natural reticence, almost incommunicable to adults. The Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents (DICA)—which serves as the benchmark for evaluating kids for mood disorders—was only formulated in the year 2000.

This, then, was the salient story of Virginia Marshall’s childhood: Washington DC, 1954. Virginia was struggling in school. She’d just failed the fifth grade, in part because of the death of her dog, her beloved and mischievous akita, Oji. On a bright morning in early summer, she was awakened by a peremptory shake of her shoulder. Even before she was fully conscious she smelled the gin—that acrid, juniper scent—and tried to burrow more deeply into the pillow.

“Wake up,” her mother said. “Out of bed, this instant.”

And Virginia was lifted and forced into her clothes—pulled downstairs and out the front door—where a driver was waiting with a car. It was a long black sedan. It had a shiny, polished roof. It looked like an insect awaiting its prey. Virginia’s father stood by and watched, impassive and silent in his military uniform, doing nothing to stop his drunken wife. “I cannot think of any need in childhood,” Freud writes, in the opening pages of Civilization and Its Discontents, “as strong as the need for a father’s protection.”

Virginia’s mother installed the little girl in the backseat. The doors locked. The engine started. The car began to move. They drove. Five minutes. Ten. Finally, they rounded a corner and there it was—the façade of St. Elizabeths—standing against the horizon like a medieval fortress.

The first federally-operated mental asylum in the country, St. Elizabeths was established in 1852 by an Act of Congress. When it opened in January 1855, the facility was officially known as The Government Hospital for the Insane, typically treating the most severe cases—the shell-shocked Union soldiers of the Civil War—men driven mad by the violations and brutalities of battle, by hiding behind stacks of corpses under musket fire, lead tearing through the dead bodies with a sickening hiss. From the combat that often degenerated into muddy brawls with bayonets.

“I’m not sad anymore,” Virginia said, looking up at the Gothic hospital towers. “I’m better.”

“We’ll see what the doctor says about that.”

“No, no, mother. I’ll be good—I promise.”

But the car kept rolling inexorably forward and so, on a curve just before the wrought-iron gates, Virginia grabbed the handle and opened the door. She leapt from the moving vehicle.

* * * *

She survived—with only cuts and bruises. But the leap did nothing to dissuade her mother, who collected her daughter, dusted her off, and showed up, on time, for the appointment at the hospital. Nurses led Virginia into a large office. The psychiatrist came through a set of double doors, doors that were easily ten-feet tall, that were made of thick burnished oak. He sat on one side of a broad, glass-topped desk. Virginia sat on the other.

A white laboratory coat. The antiseptic odor of institutional bleach. The leather of the chair; Virginia’s palms sweating against it. The window broad and full of light—with birds skittering by—their calls muffled but audible in the silence of the room. The doctor took notes. He had a bright red pencil, Virginia remembers, and his glasses were thick bifocals.

“Do you know why you’re here?” he finally asked her.

Virginia didn’t answer immediately. But when she finally did, her entire story came out in a torrent: Missing her beloved Oji, fearing her mother’s drinking, feeling abandoned by her father. The doctor listened impassively to her speech. At first, Virginia was afraid that he would judge her—but then, through tears—she gave up on worrying about how she must appear. When she’d finished, the doctor folded his hands on the table. Illumination filled the room. The windows let in light from the outside world.

“Virginia,” the doctor said, after a long silence. “Do you have any other family nearby? Any aunts or uncles? Is there anyone else you can call?”

“What do you mean?” she asked.

He leaned across the desk and handed her the telephone with its large, black rotary dial.

“You need to get out of there,” he said. “Now.”

This moment is truly an extraordinary one—a doctor reaching out to a young girl in this way—taking the girl’s side in her struggle with her troubled family. Virginia, twelve years old at the time, did the only thing she could think of. She called her father’s father, her grandfather Munson. Five days later, she went to live with him in Arlington, Virginia. But one thing still haunted her, still stuck in her imagination. When she closed her eyes at night—or even during her quieter moments during the day—Virginia still missed her beloved akita. The thing that hurt her most was simple: Oji had just disappeared. Vanished. She’d never had a chance to say goodbye.

* * * *

Every family, it seems, has that single pet—the one that’s different from all the others—the one that somehow becomes enshrined in family lore. It is the most destructive, or the sweetest, or the one who does the single most dramatic thing. Kitchen cabinets are rummaged through, garages are ransacked, duvets are gnawed and shredded. Or great odds are somehow defeated. A car fender does not kill, an illness is overcome, an unusual skill is mastered. There is a profound uniqueness to these animals. They are not human, but that’s part of why they are incredible. From within their animal selves, they summon something that confirms their individuality, their vivacity and vigor, their hold on a deep and enduring presence in our hearts and minds.

It would take nearly forty years for Virginia Marshall to find that presence, once again. It would appear unexpectedly in her life, in 1992, in an unlikely form, in a shaggy mixed-breed golden retriever named—of all things—Gonker.

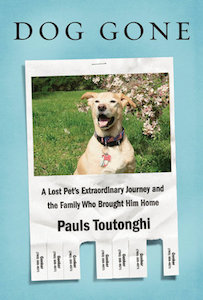

Gonker belonged to Fielding Marshall, Virginia’s son. Adopted while Fielding was a junior at The University of Virginia in Charlottesville, Gonker was a golden retriever who loved wearing sweater vests. In any room, Gonker refused to sprawl on the ground like a dog, choosing instead to sit in chairs—to perch on benches and bedsides, his paws crossed, his chin lifted. He was regal. But he had his weaknesses, too. He would, somewhat mysteriously, chase anyone in a white coat. An open trashcan was a temptation. An unguarded stick of butter? Irresistible. One Sunday, when a Virginia left a raw loaf of bread on the kitchen counter to proof—and then went briefly upstairs—Gonker ate the whole thing. It was a calamity. He nearly died. A dog’s stomach, it turns out, is an ideal environment for yeast to multiply. And when yeast multiplies it produces two notable by-products: carbon dioxide and alcohol. In retrospect, it was a little funny to watch him weave around the house, his eyes glassy, belching and farting uncontrollably as he wandered from room to room. He seemed a little drunk for days.

When her son moved home to DC after UVA, Virginia essentially adopted the dog as her own. They’d go on long walks together every day, Gonker holding, always, a long stick in his mouth, gnawing at the bark with persistent, eager teeth. She loved the way Gonker would sit at the picture window in the kitchen, watching the bluebirds in the backyard. He’d track them as they darted between the nesting box and the suet feeder. Once, Fielding caught him sitting there, his paws crossed, his head held high, his white ascot fluffed and regal, and a single, long rope of drool hanging from one side of his mouth.

“He’s imagining a bluebird sandwich,” Fielding said.

“Nonsense,” Virginia said. “The bluebirds are a thing of beauty and Gonker knows it.”

“A beautiful sandwich,” Fielding said. “He knows they’d be delicious.”

* * * *

And so, one evening in early October, 1998, late at night, close to eleven, the phone rang. Virginia was sitting upstairs in bed—next to her husband, John—reading. She almost didn’t answer. Fielding had taken Gonker hiking that weekend and the house felt emptier because of it; they were going back to Charlottesville—son and dog—and hiking the Appalachian Trail. It was a beautiful late autumn weekend, there, in the Blue Ridge Mountains. Close to sixty-five degrees and sunny—with the scent of autumn in the air and the deciduous trees firing the mountains into a blaze of yellow, red, and orange.

“Marshall residence,” Virginia said, wondering who could be calling. It was Fielding. Oh no, she thought, as soon as she heard his voice. A trace of fear shot through her body, visceral and cold.

Accidents are quick. Bewilderingly quick. It’s what survivors of serious car wrecks invariably say: I was amazed by how fast it happened. This is part of why having toddlers—or boisterous, excitable pets—can be so stressful. Disasters lurk there, just off-camera, waiting for the briefest moment to assert themselves.

This is what Fielding was saying to Virginia, some version of it. Gonker was lost. One minute, he’d been standing there, sniffing the air, lobbying intently for part of Fielding’s lunch. And then: He was gone. He’d darted after something, a swift glimpse of yellow in the trees. For a while, Fielding heard the big dog breaking twigs and bushes, and then just silence.

After fifteen minutes, Fielding had begun to worry. After an hour, he’d been seriously concerned. “Gonker!” he’d started to shout, pacing the same quarter-mile section of trail. “Gonker!” After ninety minutes, Fielding he’d begun to panic. Here was the totality of the Appalachian wilderness, confronting him with its vast size. Whereas, before, it had felt manageable, it now felt outsized and daunting. The landscape had grown in its immensity.

Sitting on the edge of her bed, talking to Fielding, Virginia kept repeating the word “lost,” again and again, asking him to describe the day in detail, to relive every step. Without her willing it, fifty years were collapsing, falling completely away. Suddenly Virginia was a girl again—weeping in the driveway of her home, looking for Oji, calling and calling him, over and over and over, without response, with only silence.

She kept asking Fielding to retell his morning because she wanted to be able to put herself there, to locate herself at the scene of the disappearance. If she could only do this, then she could get some kind of clearer sense of what had happened. She’d be able to see it. And then maybe, just maybe, she could begin to understand. But there was nothing—no realization, no understanding, no explanation—only loss. As she listened, something built inside of her, some kind of deep and unruly emotion, something from a distant, buried past.

“How could you?” she said. “How could you be so careless?” She ran her hands through her hair, massaging her forehead with her fingertips. She didn’t know where this anger—this rage—was coming from. “I just don’t understand it, Fielding. What—what is wrong with you?”

But as soon as she said these words, she regretted them deeply. He’d just been himself, and nothing else. He was her son. Her duty was to protect him, to support him, to love him—not to tear him down. And so Virginia apologized, again and again, saying that it was just bad luck, that it was uncontrollable—that it was no one’s fault. But at some fundamental level, she believed otherwise. She felt a deep and abiding shame—something that had harnessed her since her childhood. Every failure in her life, she believed, was her own. She was—somehow—the one to hold responsible. She should have been more vigilant. She should have been in control. She should have seen something like this coming.

* * * *

Fielding drove home to DC late the next night, and the Marshalls sat in the living room and drank coffee. When a loss hits a family, it doesn’t make sense. The absence of a loved one—whoever it is—just sits there, hangs in the air when everyone is together, looming over and around everyone, making them all aware of it, even if they’re not thinking about it directly.

“I can do it,” Fielding finally said. He’d washed his face but he hadn’t changed his mud-stained clothes. The knee of his jeans had torn when he’d fallen down the embankment of the ravine. He was wide-eyed. He’d barely slept—and he’d gone back out in the morning, too. “Work doesn’t matter. I’ll drive up there tonight. My boss can fire me if he wants to. I left my shirt for him to find. I have to go back. I have to show him I’m coming back.”

“Fielding,” Virginia said, “you’re overexcited.” His eyes were bloodshot and red; his breathing was rushed and ragged. “Let me get you a glass of water.”

Parents love their children in a multitude of ways. Parents can be distant, or they can be affectionate and close. They can be kind; they can, of course, be brutal. There is no such thing, really, as the story of a child; there is only the story of a parent and a child, and the ways the parent built, or destroyed, or relinquished the bond with the child.

In trauma-survival groups, it is common for survivors to fill out a checklist to see how grave parental wounding is:

- I was not cherished and celebrated by my parents simply by virtue of my existence. I thought I had to be different or perform to be accepted.

- I did not have the experience of being a “delight” to my parents and those around me.

- I did not hear affirmation—words of acceptance and validation.

- I did not have a parent that took time to understand me or encourage me to share who I was: what I felt, what I needed and what I wanted.

These are the first few bullet points of the Mother/Father Wound assessment, a common diagnostic instrument. But these were also the things Virginia sought to escape; they pointed to the devastation that she wanted, so deeply, not to inflict.

That night, after she’d hugged her son and kissed him goodnight—she’d walked back downstairs. She’d rummaged through a drawer and found a big Rand McNally map of the state, stuffed in a drawer under the microwave. She’d unfolded it and spread it across the kitchen table. It was an arterial tangle of interstates and small highways, almost unmanageable in its intricacy.

The area of the Blue Ridge Parkway where Gonker had been lost was almost two hundred miles outside of D.C. Virginia closed her eyes and tried to picture it. She remembered it as intimidating, a smear of green mountains—hot in the summer, but wind-blown and snow-bound in the winter. Virginia was a state of contrasts. Washington, which was at its easternmost limit, was a tangle of concrete suburbs and malls—racially and ethnically diverse, busy, nearly a million people in the metropolitan area. The rural parts of the state, however—the areas around Catawba, for example—were quite different. They were agricultural. They’d voted heavily for Bob Dole in the 1996 election; the area near the trail was dotted with tobacco and soybean farms, and industrial-sized commercial turkey factories.

Virginia took out a yellow highlighter and ran it over the county names: Orange, Greene, Albemarle, Nelson, Amherst, Rockbridge, Rockingham, Augusta. Virginia repeated these words again and again, quietly, tracing over the page with her fingertips. She imagined the words as a magical thing—names rising up off the map and filling the air around her with their sound. And then John was standing behind her in the doorway to the kitchen.

“What are you doing?” he asked.

“He’s probably so cold,” Virginia said, turning to John. “It must be forty degrees out there tonight in the mountains.”

John put his hand on her shoulder. “We’ll find him,” he said. “I know we will.”

“John, stop,” she said. Her voice was angry, full of reproach. “How can you say that?”

“Easy,” he answered. “Because I believe it.”

* * * *

And so, and so—The Search Began.

Virginia procured stacks of phone books from the public library. She spread the map out in front of her, and pens and pencils and highlighters, and a list of ideas. Leads. The important question was: where to call first?

Animal hospitals, she decided. They would be the most likely source of information. Then she’d try all the pounds, the animal-control facilities in the small towns on the wooded slopes of the vast Appalachian mountains where Gonker had disappeared. Then the police in each municipality. And of course churches. And grade schools. And libraries. Then she would call every newspaper and send them faxes. And then charitable organizations—the Elks Lodge, the Rotary Club, the VFW. Then ranger stations. And city halls.

And that would only be the beginning. She also planned on calling any businesses that might have a central place in the communities that she was scouring from here, from a distance: any general store, of course, and the Blue Ridge Parkway Authority, and local credit unions, and then radio stations, and newspapers, and TV stations—whose news anchors would be listed in local phone books and possibly eligible for a call at home. Then, of course, she’d set in on the secondary leads—anyone recommended by the first set of calls. And then the tertiary leads.

As she made contacts, she’d keep every conversation sorted in a color-coded file folder. She’d started a countdown on a bright-orange pack of oversized Post-it Notes. She’d numbered each sheet—nineteen to zero—representing how many days they had until the fludrocortisone acetate and cortisol ran out. These were the synthetic hormones that kept Gonker alive; once they left his bloodstream, hope would be truly lost.

To make matters worse, it was early autumn, the beginning of the hunting season. Gonker, moving through the leaves, could easily be mistaken for something else, for a larger animal—a blur of motion, a deer darting for cover. Virginia imagined him shot by hunters. She imagined him wounded and staggering through the forest, collapsing on the cold ground, blood coursing out of him. There were also coyotes. To a pack of coyotes, Gonker would be an ideal delicacy. He’d a soft and chewy, pleasantly dog-flavored snack.

* * * *

There are hundreds of stories in every popular culture about dogs, especially about dogs and their heroic, unwavering faithfulness to human beings. Every country, it seems, has some kind of famous, legendary canine. Hachiko in Japan, of course. In Cádiz, Spain, a plaque honors Canelo, a dog whose owner died during dialysis at a local hospital; Canelo waited outside of that hospital for twelve years, hoping that his owner would once again walk through the revolving doors and take him home. In Argentina, for the past nine years, Capitán, a German shepherd, has been watching over his master’s grave, refusing to leave—even in the most inclement weather. In Tolyatti, Russia, a bronze statue called The Monument to Devotion honors Constantine, the dog who returned, every day for seven years, to the intersection where his family were all killed in a car accident.

American culture also has famous stories of dogs traveling long distances to find their departed owners. Bobbie the Wonder Dog, for example, became famous for traveling twenty-five hundred miles to return to his family in Silverton, Oregon. This devotion is perhaps more poignant in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, when humanity’s worst aspects have been on such ample display. The mechanized slaughter of modern warfare, the incineration of hundreds of thousands of people with a single bomb, ethnic cleansing and tribal warfare in every part of the globe, the horrors of genocide—all of these are part of our current sense of ourselves, of our belief in the limits of what people will and will not do. But dogs are almost always decent—unchanging, unaltered, predictable. And their attitude toward us is unquestioningly kind. Dogs can make us more human—or more like what we imagine a good human to be. If we listen.

Maybe this is why their loss is so heartbreaking. We’re skewered by the lost-animal fliers stapled to telephone poles, by the pleading posts across all forms of social media, begging for news of a missing companion. And it’s not just dogs. Here’s the photograph of Charlie, the beloved family cat, yawning into the camera, fat and fluffy. Here’s Brantley, the eleven-pound rabbit, wearing his finest holiday sweater, a picture taken just before he disappeared in the middle of the night, digging his way underneath the fence in the backyard, uprooting the damask rose.

Virginia’s handwriting in the faxes she sent across the state of Virginia expressed panic. This much is clear: the words were uneven and the letters didn’t come neatly together. She was writing quickly, provisionally, sending notes to her growing list of contacts. But something else seems to live in those letters. In their stems and flourishes, there seemed to be a wistful hope. And she was begging—pleading, really—for help. Any kind of help. This is my beloved animal, her handwriting seems to say. Won’t you help me find him? Won’t you, kind stranger, help bring him back to me?

* * * *

“The Appalachian Trail leads not merely north and south,” wrote Harold Allen in 1934, “but upward to the body, mind, and soul of man.”

In 1900, the trail’s first great visionary, Benton MacKaye, graduated from Harvard University. After his graduation, MacKaye took a celebratory six-week hike, following a series of trails maintained with varying degrees of stewardship, relying on hand-drawn maps that he’d procured from numerous sources. Standing atop Stratton Mountain (which, today, is a ski resort and twenty-seven-hole championship golf course), MacKaye had a vision of a single, long trail connecting New England and the South, cutting through the peaks and valleys of America’s Eastern Seaboard. He saw a place that would offer, as the plaque on Springer Mountain in Georgia now says, “a footpath for those who seek fellowship with the wilderness.” It would take thirty-seven years for MacKaye’s vision to become reality.

Any number of corporations would be overjoyed to develop the land that lies beneath the trail; it’s rich in minerals, in coal, in natural gas. And yet the idea of the Appalachian Trail has, over the last century, trumped any potential industrial development. This is in part because of the grandeur of its open spaces; the scent of weather—rain, for example—gathering thick in the air, gathering on one side of a hill or a mountain, and then sweeping down toward you; rain on your skin; leaves rustling with each step, the feeling of mud on hands, on boots, underfoot; leaves changing color, leaves falling, snow on skeletal trees.

Two hundred sixty-five mountains; 255 shelters, all of them drafty and wood-floored. A series of waypoints with colorful, unusual names: Peaks of Otter, Blackhorse Gap, Rockfish Gap, The Priest. Twenty-two hundred miles of packed dirt and gravel path, crossing fourteen states; thousands of species of plants and animals.

And one lost golden retriever. He was gone, but who would find him? Who would bring him home?

From DOG GONE. Used with permission of Knopf. Copyright © 2016 by Pauls Toutonghi.