Does Fiction Actually Make Us More Empathetic?

On 5 Works that Explore the Connection Between Art and Understanding

Writers and intellectuals are perhaps no different from other people in their need to justify what they do through something other than the fact of their personal attachment to it. Nonetheless, literature does differ from most other human occupations in that it apparently lacks a clear practical purpose. In this regard, people who dedicate their lives to civil engineering or ornithology, for example, may have it easier than writers. The social relevance of what they do (build things, study nature) is more easily explained and acknowledged. When it comes to presenting the case for literature, to arguing that stories and poems can, at least potentially, offer us something more than the commodified entertainment duly provided by the culture industry, things may at first appear to be less self-evident.

In recent debates about the value and purposes of literature, however, a recurring argument has proven quite persuasive in connecting literature to something arguably more fundamental for human existence than bridges or woodpeckers. One might call this “the empathy argument.” Its bottom line is the idea that fiction allows us to exercise the capacity to see the world from different perspectives, and thus helps us become more understanding and tolerant. Anyone who’s been on a steady diet of book reviews or literary festivals over the past few years has likely been exposed to one or more versions of this argument, often delivered by otherwise cranky authors in a spirit of self-congratulatory benevolence. Its current popularity is plausibly related to its effectiveness in convincing people that they should really care about literature, which instead of a declining cultural form now comes to be regarded, for everyone’s relief, as a crucial meeting point between art, psychology and democracy. Such is the apparent cogency of these exhortations that empathy and related notions (such as “moral imagination”) have come to constitute the main tropes of contemporary liberal answers to the question of the relevance of literature.

Although such an argument may assume many different forms, its basic point is that empathy entails an essential link between the imagination, emotions and morality. As a capacity to understand other people’s feelings and reasons, empathy involves a certain exercise of the imagination, the ability to momentarily, as it were, step out from one’s personal perspective on things and consider them from a different standpoint. What would I do, or how would I feel, if I were in his or her place? This kind of “what if” question already demands some degree of narrative articulation, and could be taken to be a fictional gesture in itself. On the other hand, reading a work of fiction–or at lest a certain type of fiction–can be said to engage us in precisely this sort of imaginative displacement, exercising and (so goes the argument) expanding our faculty of empathy. In short, literature would be justified as a practical lesson in morality, teaching us to look beyond our own interests, and providing an understanding of the moral implications of our decisions which would be at once more concrete and nuanced than any set of general values or rules.

Two fairly recent examples of “the empathy argument” may give a better idea of the kind of conceptual crossroads implied in current discourses about literature and empathy. The first one comes from a conversation between best-selling psychologist Andrew Solomon and Paul Holdengraber, published on this website a couple of months ago: “Literature is a means of putting yourself in other, often uncomfortable shoes,” Solomon said. “You can’t, in any ordinary life, experience all of what the world has to offer. If you lived a thousand years you wouldn’t do it. But if you read, you can expand your education so hugely and so vastly, by thinking, Oh, well that’s a way of thinking about that.” The second example, which clearly draws out the political implications of Solomon’s remarks, is a passage from Barack Obama’s long, fascinating, dialogue with novelist Marilynne Robinson published last November by the New York Review of Books. In what was perhaps the most discussed moment of their conversation, Obama directly connects the reading of novels to his education as a citizen: “When I think about how I understand my role as citizen, setting aside being president, and the most important set of understandings that I bring to that position of citizen, the most important stuff I’ve learned I think I’ve learned from novels. It has to do with empathy. It has to do with being comfortable with the notion that the world is complicated and full of grays, but there’s still truth there to be found, and that you have to strive for that and work for that. And the notion that it’s possible to connect with some[one] else even though they’re very different from you.”

The idea that the significance of literature “has to do with empathy” and some sort of political education is not entirely new, to be sure. In his Poetics, a work on drama which remains to this day the major philosophical reference for Western discussions of narrative fiction in general, Aristotle argued that the ultimate effect of a tragical play was catharsis, the purging of passions, which depended on some sort of identification between the audience and the tragic hero. In modern times, Friedrich Schiller’s On the Aesthetic Education of Man (1794) is probably the most influential defense of art’s formative role in the political education of free citizens. If we had to look for a recent work where all of these threads (empathy, fiction and democracy) are closely sewn together, however, it would probably have to be in Harper Lee’s classic novel To Kill a Mockingbird. It is hard to think of any other modern literary work which so explicitly sets out to defend the relevance of empathy to democracy (in the admonishing words of lawyer and model citizen Atticus Finch: “You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view”), while at the same time hoping to foster it concretely through the imaginative possibilities of fiction.

So the novelty isn’t so much in the argument itself, but rather the intellectual climate in which it has become so familiar as to seem a sort of truism. It is precisely this appearance of self-evidence which calls for a closer look at the premises and implications of “the empathy argument.”

Perhaps its most obvious problem is that its advocates rarely bother to consider the possibility that empathy may be misleading. Imagining the other could end up being the most efficient way of ignoring his or her singularity. Empathy, after all, implies that we put ourselves into the place of the other, and it may well be possible that in so doing we end up projecting sameness and drawing up false inferences. The focus on empathy also seems to ignore the many ways in which fictions and poems can affect and transform us through verbal, poetic effects. In aesthetic terms, “the empathy argument” unmistakably favors fiction over poetry. And many of its assumptions rely on a shallow equation of literature with a very specific sort of psychological realism that is today the hegemonic model of what the book industry sometimes calls, in a sort of jesting deference, “serious fiction.” Finally, should we accept that literature be defended for its promotion of civic virtues? Something in Obama’s description of literary experience renders it too tame, ignoring its transgressive possibilities.

The following reading list takes a closer look at some of the most influential recent arguments connecting empathy and related notions to literature and democracy. It also considers an alternative perspective which suggests that we have to look for different concepts if we want to account for some of the defining and most politically relevant features of modern literature.

How to Cure a Fanatic, Amós Oz

This slender polemical volume might have been described as a pamphlet, if its author was not so blatantly opposed to radicalism of any kind. Calling himself “an expert in comparative fanaticism,” Oz examines his subject in detail in this book, identifying its causes and suggesting possible remedies to “cure” the fanatical mind. His basic point, simply put, is that fanaticism is at bottom a failure of the imagination—an incapacity to step away from one’s own perspective and see the world from a different point of view. The inaugural violent act of any fanatical movement, according to Oz, is its unimaginative effacement of alterity: “In a small way, in a cautious way, I do believe that imagination may serve as a partial and limited immunity to fanaticism,” he says. “We need imagination, a deep ability to imagine the other, sometimes to put ourselves in the skin of the other.”

How to Cure a Fanatic also turns out to be a meditation on the political significance of literature and its connection with democratic life, a recurrent theme in many of Oz’s interviews, lectures and essays. In a 2009 interview for the New York Times he would go so far as to say that this empathetic exercise of the imagination is the common source of all his writing: “That’s what I do for a living. I get up in the morning, I drink a cup of coffee, I sit down at my desk and I start to ask myself: ‘What if I were him? What if I were her? How would I feel? What would I say? How would I react?’”

At the Same Time, Susan Sontag

In March 2004, nine months before her death, Susan Sontag flew to South Africa to deliver a lecture in honor of Nadine Gordimer, the Nobel Prize-winning novelist and anti-apartheid activist. At the Same Time is Sontag’s final reflection on the moral and political significance of literature, which in her lecture comes to be largely equated with narrative. The inherent moral importance of narrative, Sontag argues, lies in its ordering and finitude. A narrative plot is, by definition, a hierarchical and limited structure, in which events are accorded different relevance depending on how they relate to the development of the main intrigue. The distinction between important and accessory events, situations, characters, is understood by Sontag to be a necessary condition for any moral reasoning at all. Morality is not simply concerned with decisions between good or bad. Rather, it involves a decision on what is more or less important, what matters to us, what is or not worthy of our attention: “When we make moral judgments, we are not just saying that this is better than that. Even more fundamentally, we are saying that this is more important than that. It is to order the overwhelming spread and simultaneity of everything.” Literature, in other words, is committed to the moral significance of deciding what we care about. A narrative implies such a choice, in as much as it always tells a certain particular story and leads it to its completion: “Endings in a novel confer a kind of liberty that life stubbornly denies us: to come to a full stop that is not death and discover exactly where we are in relation to the events leading to a conclusion (…) The pleasure of fiction is precisely that it moves to an ending. And an ending that satisfies is one that excludes.”

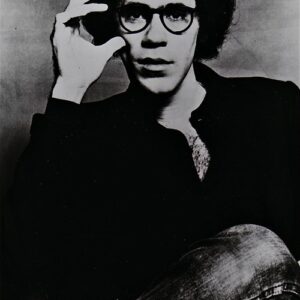

This is Water, David Foster Wallace

Wallace’s famous commencement speech at Kenyon College isn’t specifically concerned with literature or narrative, but rather with what he takes to be the real goal of a “liberal arts education.” His point of departure is “the single most pervasive cliché in the commencement speech genre,” namely, that “a liberal arts education is not so much about filling you up with knowledge as it is about, quote, ‘teaching you how to think.’” This is a cliché Wallace’s speech will in fact endorse, reflecting upon what “teaching you how to think” effectively means. His answer to this question is somehow similar to Susan Sontag’s argument about morality having to do with a decision about what is more or less important to us: “The really significant education in thinking that we’re supposed to get in a place like this isn’t really about the capacity to think, but rather about the choice of what to think about.” Thinking about, here, also means caring about, paying attention to. And Wallace’s suggestion of what we ought to care about, simply put, is: other people. Caring about ourselves is for him a sort of psychological inevitability—“Everything in my own immediate experience supports my deep belief that I am the absolute center of the universe (…) It is our default setting, hard-wired into our boards at birth”—so that concern for others is also an escape from a sort of tragic, solipsistic self-involvement that defines ordinary experience: “The really important kind of freedom involves attention and awareness and discipline, and being able truly to care about other people and to sacrifice for them over and over in myriad petty, unsexy ways every day.”

Not for Profit, Martha Nussbaum

Martha Nussbaum’s manifesto on “why democracy needs the humanities,” as the subtitle of this book states, draws upon her decades-long inquiry into the connections and mutual implications between art, emotions, imagination, and morality. Although virtually every direct mention of literature in this book is followed by the complement “and the arts,” literary works have long figured as Nussbaum’s favored objects of discussion concerning these matters. In “Not for Profit,” the emphasis falls on the idea that literature (here we must add, “and the arts”) has a fundamental formative role for life in society because it allows for the cultivation of our capacity for understanding and sympathizing with one another: “Citizens cannot relate well to the complex world around them by factual knowledge and logic alone. The third ability of the citizen, closely related to the first two, is what we can call the narrative imagination. This means the ability to think what it might be like to be in the shoes of a person different from oneself, to be an intelligent reader of that person’s story, and to understand the emotions and wishes and desires that someone so placed might have.”

Nussbaum does qualify her argument with some reservations regarding the possible limits of empathy: “The empathetic imagination can be capricious and uneven if not linked to an idea of equal human dignity. It is all too easy to have refined sympathy for those close to us in geography, or class, or race, and to refuse it to people at a distance, or members of minority groups, treating them as mere things.”

The Antinomies of Realism, Fredric Jameson

What defines modern realism for Jameson is not any kind of naive epistemological claim to present the world as it really is. Rather, realism involves a struggle with the contingency of modern life and its resistance to any kind of meaningful ordering: “Experience—and sensory experience in particular—is in modern times contingent: if such experience seems to have a meaning, we are at once suspicious of its authenticity.” As Marx wrote of bourgeois society, in modern times “all that is solid melts into the air,” traditional values and ways of life are disrupted and turned upside down, so that there is an ever widening gap between individual experiences and our capacity to interpret them and render them meaningful. In Jameson’s words, modernity imposes an “irreconcilable divorce between intelligibility and experience, between meaning and existence.” In this context, Jameson argues, literature’s relevance is not so much in helping us understand each other, but in its constant attempt to account for those new experiences for which we don’t even have a name yet. This is what Jameson calls “affect” a kind of sensory experience which “somehow eludes language and its naming of things (and feelings), whereas emotion is preeminently a phenomenon sorted out into an array of names.” Emotion comes to be identified with convention, its names being part of a social classification of feelings, while affect constantly points to the incommensurability between ruling conventions and the constantly changing conditions of life. It refers to what is not yet incorporated into the status quo, and so can be seen as a prefiguration of the possibility of radical historical change, pointing towards the new and the unknown, beyond current forms of social life.

Miguel Conde

Miguel Conde is a critic and journalist based in Rio de Janeiro. His articles, essays and book reviews have been published by some of the main Brazilian newspapers, such as O Globo, Folha de S. Paulo and Valor. He was the curator for two editions of Flip, the international literary festival at Paraty, and a Visiting Research Fellow at Brown University. He is the author of Clutter (Pipoca Press, 2016) and a PhD candidate at Rio's PUC university.