Sometimes I can feel my bones straining under the weight of all the lives I’m not living.

–Jonathan Safran Foer, Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close

Sex trades on the thrill of discovering, over and over again, that we

are unknown to ourselves. . . . What makes for adventure is not only the

novelty of the Other, although that helps, but the Otherness of the self.

–Virginia Goldner, “Ironic Gender, Authentic Sex”

What if the affair had nothing to do with you?

That question often seems ludicrous to a partner who has been cast aside for a secret lover, lied to, two-timed by their one and only. Intimate betrayal feels intensely personal—a direct attack in the most vulnerable place. However, looking through the lens of the damage it caused the aggrieved partner, we see only one side of the story. Cheating is what they did to their partner, but what were they doing for themselves? And why?

Holding the dual perspective—the meaning and the consequences— is a central part of my work. Phase 1 focuses primarily on the what: the crisis, the fallout, the hurt, and the duplicity. Phase 2 turns to the why: the meaning, the motives, the demons, the experience on its own terms. Listening to these revelations with an open mind is an essential part of the recovery process, for all parties involved.

“Why do people stray?” is a question I have been asking continuously for the past few years. Whereas in literature, we are invited to eavesdrop on the complex yearnings of married miscreants, in my field their motives tend to be reduced to one of two options: either there is a problem with the marriage or there is a problem with the individual. Hence, as Michele Scheinkman has pointed out, “What was once for Madame Bovary a search for romantic love is today. . . encased in a framework of ‘betrayal’ that is less about love and desire and more about symptoms in need of a cure.”

The “symptom” theory goes as follows: An affair simply alerts us to a preexisting condition, either a troubled relationship or a troubled person. And in many cases, this holds true. Plenty of relationships culminate in an affair to compensate for a lack, to fill a void, or to set up an exit. Insecure attachment, conflict avoidance, prolonged lack of sex, loneliness, or just years of being stuck rehashing the same old arguments—many adulterers are motivated by marital dysfunction. And plenty has been written about trouble leading to trouble. However, therapists are confronted on a daily basis with situations that defy these well-documented reasons. How are we to interpret these?

The idea that infidelity can happen in the absence of serious marital problems is hard to accept. Our culture does not believe in no-fault affairs. So when we can’t blame the relationship, we tend to blame the individual instead. The clinical literature is rife with typologies for cheaters—as if character always trumps circumstance.

Psychological jargon has replaced religious cant, and sin has been eclipsed by pathology. We are no longer sinners; we are sick. Ironically, it was much easier to cleanse ourselves of our sins than it is to get rid of a diagnosis.

Strangely, clinical conditions have become a much-coveted currency in the recovery-from-adultery market. Some couples arrive in my office with a diagnosis in hand. Brent is eager to don the mantle of pathology if it means finding an excuse for twenty years of gallivanting. His wife, Joan, is less enthusiastic and lets me know what she thinks about it: “His therapist told him he has an attachment disorder because his father abandoned him and left him alone to take care of his mother and his sister. But I tell him, ‘You can’t just be a pig anymore? You need a diagnosis?’”

Jeff’s wife, Sheryl, just discovered a slew of evidence that he has been cruising BDSM* sites and meeting strangers for sex. After many sessions with a therapist, Jeff is now convinced he is a “sex addict” who self-medicates his depression in the dungeon. His wife agrees, and indeed, it may be true. But medicalizing his behavior should not be used as a deflection from honestly exploring the uneasy territory of his kinky predilections. It’s easier to label than to delve.

If psychological diagnoses are not convincing enough, there’s always the booming world of popular neuroscience. Nicholas, whose wife, Zoe, had been having an affair for more than a year, looked visibly brighter when he arrived for our last session brandishing the New York Times. “Look!” He pointed to the headline: “‘Infidelity Lurks in Your Genes.’ I knew that because of her parents’ open marriage, her sense of morality is weaker. It’s hereditary!”

There is no doubt that many renegade spouses do display signs of depression, compulsion, narcissism, attachment disorder, or plain sociopathy. Thus, at times, the right diagnosis finally lends clarity to an inexplicable and distressing behavior, both for the person enacting it and for the person suffering the consequences. In those situations, it is a useful tool that helps to lay out a path to insight and recovery. But too often, when we jump to diagnosis too quickly, we short-circuit the meaning-making process.

__________________________________

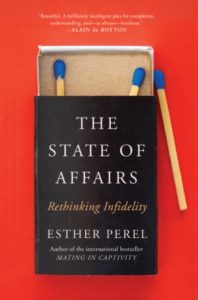

From THE STATE OF AFFAIRS by Esther Perel. Used with permission from HarperCollins. Copyright 2017 by Esther Perel.

Esther Perel

Esther Perel is a couples and family therapist with a private practice in New York City. She is on the faculty of the International Trauma Studies program at Columbia University, is a member of the American Family Therapy Academy, and has appeared on many television programs, including The Oprah Winfrey Show, Good Day New York, CBS This Morning, and HBO's Women Aloud. She lives in New York City with her husband and two children.