Six travelers spent three hours rushing over Vietnam’s national highway number one. The bus they were riding had been swept up in a deluge of motorcycles. Motorcycles zipped along the road, and more waited by the curb. The curbside bikers were waiting for scheduled pickups, or hanging around hoping for customers. Bikes carrying up to four people at a time could be seen from the bus windows. Yona also watched the passing Vietnamese flags, stuck in the ground at equal distances, and street vendors hawking bags of bread and noodles. Two-story houses, simple except for their beautifully decorated eaves and elaborate front gates, glided by, alongside tangles of electrical lines that resembled thick hair. The travelers recorded each moment, clicking their camera shutters as they glanced out of the windows at an outdoor wedding, and later when they drove past a cemetery busy with funeral-goers.

Among all the views on the road, what caught Yona’s eye most was the Korean writing. She saw Korean words written on small items, like vests labelled with the phrase “quick delivery” and T-shirts with unexpected slogans like “hazardous materials vehicle”, but she also noted Korean on buses, like those adorned with misspellings such as “automatic rood” instead of “automatic door.”

“Right now in Vietnam, we have a lot of buses covered with maps of the old Seoul transportation system,” the guide explained. “People import old Korean buses to Vietnam, and buses with even a few Korean words on them sell for more. This means that a lot of people just go ahead and put Korean stickers on the vehicles they’re selling. If you look carefully, you’ll see Korean letters all over the place, even though what’s written doesn’t always make sense. Recently I rode a bus that, according to the map on the outside of the vehicle, went by Jungang Market, Gyeongbokgung Palace and Mapo-gucheong. Of course, that wasn’t the actual route. Isn’t that funny?”

The guide had energy suitable for a person used to long journeys. Her name, she said, was “Lou,” and she was Korean—even if her name wasn’t. She spent ten months each year in places like Vietnam, Mui and Cambodia, but Mui was her favorite. Accommodation there was of especially high quality, she said.

Highway one first hit the coast at the seaside town of Phan Thiet. The town was a checkpoint you had to pass through to reach Mui. The bus stopped in front of the entrance to Phan Thiet’s largest grocery store. Lou rose from the passenger seat.

“We’re going to take a break here for the next hour,” she told the travelers. “There are no large supermarkets in Mui, so buy any necessary items or snacks you’ll want to bring with you.”

An hour later, the passengers boarded carrying remarkably similar purchases: products like G7 coffee, Oral B toothbrushes and nep moi, a Vietnamese rice liquor. Everyone carried bundles of toothbrushes as well. Lou had informed the group that toothbrushes were especially cheap in Vietnam, so they’d all been sure to buy a few, even though some of the travelers had initially laughed at the idea. “We’re on a disaster trip,” they’d exclaimed. “Aren’t toothbrushes a bit too ordinary to bring on an adventure like this?”

“Maybe Mui is more ordinary than we’re expecting,” the man facing Yona said. There were two men on the trip. One was a college student who’d just been released from his compulsory military service; he’d been preparing for the trip since the beginning of his conscription. The other man looked to be around forty, but he turned out to be much younger. He was only one year older than Yona, and he told her he was a screenwriter. This was the man sitting across from Yona.

None of his works had been turned into movies yet, but he had sold more than ten screenplays to production companies, and he supported himself with a variety of side jobs. The other two female travelers, besides Lou, were a mother and child. The woman was an elementary school teacher who’d brought along her five-year-old daughter. Yona’s fellow adventurers began to ask her questions.

“Are you married yet?” one person asked.

“How old are you?” demanded another.

“What kind of work do you do?”

She couldn’t say that she was on a business trip, or that the person who’d created this package was a coworker. She wondered if their guide, sitting in front of them, was aware of the personal details of her clients. Thankfully, all Lou seemed to know was the contents of everyone’s passports. Yona tried to come up with an appropriate fake job for herself. She decided she’d be a 33-year-old independent café owner: a life Yona had daydreamed about. If she ever quit her job at Jungle, Yona really did want to open a store that sold coffee and pie.

“The truth is, I paid for this trip with my student loans,” the college student told the others. “Trips like this aren’t usually expensive, so I figured it wouldn’t be too hard on my finances. And the insurance that comes with the package is pretty generous, too: if anything happens to me on this trip, the massive payout Jungle will send my parents is going to pay back the debt I owe them for raising me!”

Yona tried to come up with an appropriate fake job for herself. She decided she’d be a 33-year-old independent café owner: a life Yona had daydreamed about.It seemed like the college student had said this as a joke, but the guide wore a serious look on her face. “As long as you pay attention to your surroundings, you’ll be fine. Accidents that occur because of broken rules aren’t covered.”

“Oh, I know, I know,” the boy replied. “Honestly, I’ve always had a lot of interest in trips like this, trips that do good for the local community. My friends all want to go see museums or castles, but I don’t care about those things. By the time our trip ends, I want to be inspired to live dynamically. Of course, if I die, I’ll be helping out my parents financially, at least.”

As soon as the student repeated his joke, Lou clarified once more.

“There’s no chance you’ll die,” she asserted. “Our Jungle system isn’t something haphazardly cobbled together.”

The college student shook his head in annoyance and turned his gaze to the view outside the window. Yona had discovered two potential problems during the conversation. One was that the trip probably wasn’t going to live up to the student’s expectation of ethical and locally engaged travel. The other was that Jungle’s system didn’t actually guarantee safety one hundred per cent. Yona thought of several safety incidents Jungle had dealt with. The causes of death were drowning, car accident and feverish illness; floods, crashes and fevers were not, of course, the disasters the travelers had chosen when planning their trips. The deaths were unadvertised disasters, unexpected by the travelers. From what Yona knew, Lou may have thought her assurances reflected the truth, but that didn’t mean there were no accidents. It was just that news didn’t spread, or it did so slowly.

They’d begun to pick up the fishy smell of anchovies in Phan Thiet harbor, and it had continued to waft into their nostrils throughout the crossing to Mui island. Yona breathed in deeply. This smell was probably nuoc mam. It was an odor she knew only by sight, a word she’d read in guidebooks. Nuoc mam, a kind of fermented anchovies, changed the flavor of any other ingredient it touched. In this part of the world, it was the conqueror of mealtimes. Mui lived by its nuoc mam. “Mui’s mornings are filled with the hubbub of fishing, and its nights with the smell of fresh catches fermenting in salt.” That was the first sentence of a book she had read about Mui. But the statement could no longer be written in the present tense, as most of Mui’s labour force had left for nearby Vietnam and nuoc mam was now made in Phan Thiet. Even so, you could certainly still smell in it Mui.

Yona didn’t mind the fishiness. Like the stimulating odor that hit your nose when entering a musty house, or a new place, it lasted only a moment. Most people grew used to the smell of their new surroundings, and never again experienced the exciting initial pungency.

The bus drove down a road lined with gingko trees. Mui was already dark. It wasn’t easy to see what lay at the end of the road. Once Mui had drifted into night, you couldn’t see a single thing on the island, not even neon signs from a red light district. The total blackness made the entrance to their lodgings seem even brighter. The bus stopped in front of a resort called “Belle Époque”, whose sign stated that it was a “Gift From Nature: Private Beach Resort; All Rooms With Ocean Views.”

“It’s nice to meet you all. Welcome to Mui.”

The manager, a local, greeted them in fluent Korean. Yona crossed the lobby and looked at the far-off ocean. The resort’s rooms consisted of individual bungalows that stood above the ocean on stilts; a 20-meter wooden bridge connected the cabins to the beachfront. Yona’s bungalow was right on the beach. An employee opened the door to her room and began to show Yona around. Her accommodation featured curtains that opened and closed automatically, a TV and speakers, a minibar, a safe and customizable lighting: nothing out of the ordinary for a luxury resort. Next, the employee pressed a button on the remote control in his hand as he introduced one of the resort’s “unique features.” The button turned on two enormous lights, shaped like a pair of eyes, which hung next to the front door on the outside of the cabin.

“You can use these eyes to express your wishes,” the employee explained. “If you close both, it means ‘do not disturb’, and if you open them, it means ‘please clean’.”

The night was deep, and inside their bungalows, the travelers adjusted to unfamiliar darkness. Most of the rooms were set to “do not disturb,” but the eyes on the teacher’s bungalow opened and closed repeatedly. Yona could see the woman’s daughter leaning against their window as she pressed buttons on the remote over and over again.

Yona sunk into her sofa. The white linens on her bed looked clean enough to wrap her body in them without worry. On one side of the tub, there was a bag filled with rose petals, and the ocean dozed a few meters below. Yona hadn’t had a break like this in a long time. This might be a better trip than I expected, she thought. It was an unfamiliar feeling, thinking that she could miss this place after she left. She mused about the expectations that travelers carried: the expectation of the unexpected, and of freedom from the weight of the everyday.

__________________________________

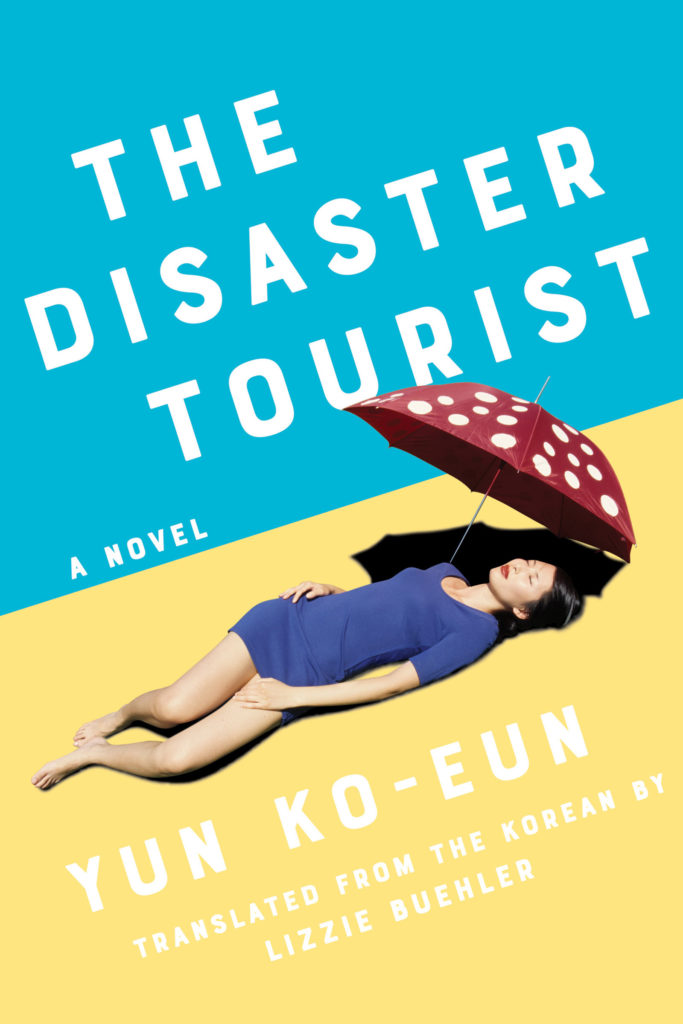

Excerpted from The Disaster Tourist by Yun Ko-eun, translated by Lizzie Buehler. Copyright © 2020. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Counterpoint Press.