Defining the Ethics of the Writer and Journalist's Gaze

Spencer Wolff on Refugee Portraits and Migrant Depictions

The image above is a photograph taken at the home of Cédric Herrou, a French farmer celebrated for housing and aiding thousands of primarily African refugees since 2015. The date is June 12th, 2017, near the height of what has been labeled Europe’s “migrant crisis.” It is a single moment from hundreds of hours of footage, shot as part of a follow-up piece to my short documentary for The Guardian that chronicled the refugee situation on the French-Italian border and the multiple prosecutions against Herrou.

In the image, it is late morning. The men—and they are all men—are drinking coffee and waiting for their clothing to dry. All of them, without exception, have crossed great swathes of Africa, by foot or bus or smuggled in trucks or vans. They have braved the battlefields of Libya. Some have recently escaped from modern slavery. Some have survived torture. All of them were packed into overcrowded boats for a hazardous voyage across murderous seas. All of them have dealt with incalculable danger and loss.

Now they are at rest. They sit and recover before initiating another perilous leg in a perilous journey. The network of trains and human solidarity that carry arriving Africans across the militarized French-Italian border has frequently been dubbed a “French Underground Railroad,” with all the implicit dangers and emancipatory hopes such a characterization implies.

The day after this photo was taken, I joined two volunteers in leading these men, along with nearly 40 other individuals, to a late morning train. Slightly over an hour later they arrived in Nice, where the volunteers brought them to a government office to apply for asylum.

In the image, the men appear safe and at ease but our eyes are misguided. The power of this photo stems from what is hidden beyond its edges. At the time it was taken, somewhere between three to five military posts manned by armed soldiers encircled Herrou’s farm. Above that ostensible haven flew drones and helicopters. Any “African”—read: black or Arabic-looking individual—stepping beyond the limits of the farm was subject to muscular deportation and often casual words of hatred.

The men pictured in this image are, in fact, prisoners. They can only travel to Nice under a court order arduously won by Herrou’s lawyers. A harsh apparatus of surveillance and domination hangs over them like an invisible net, and an invisible fence encircles them. They are being watched. And let us not forget, they are also being filmed. Invisible as well, in this image, is the image-maker himself: me, the journalist camouflaged by his own lens.

*

I once came before men like this in a very different capacity. When I worked at the United Nations Refugee Bureau (UNHCR) in Rabat, Morocco, I helped interview asylum demanders, evaluated living situations, and weighed a refugee’s chances for resettlement. Instead of sitting with them, I sat across from them, garbed in an invisible mantle of authority. Instead of listening, I judged.

At the UNHCR, we were tasked not with understanding the full substance of an individual’s life, but rather with extracting the bare elements of a claim from their testimony. Our natural stance was disbelief, our ears attuned to any inconsistency.

The author Dina Nayeri has written beautifully about how such bureaucratic failures of imagination have disastrous consequences for asylum demanders. In one article, Nayeri describes a UK caseworker who refused to believe that a two-year romance could unfold in the streets of Kabul and yet “leave no trace: not a single photo, note or text.” The caseworker, Nayeri notes, could not comprehend that in Afghanistan relationships have to be conducted in secret. “You’d have to teleport to Afghanistan to understand,” but that would require a stroke of empathy and the capacity to imaginatively inhabit a foreign world with customs different from one’s own.

The reporter holds certain advantages over the fiction writer: a more permissive public and wider license to tackle controversial themes.

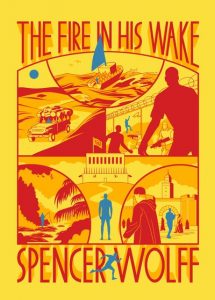

My frustration with this work—and with a failure of imagination so vast that it provoked a refugee-led assault on the Rabat bureau of the UNHCR in 2009—inspired me to write my forthcoming novel, The Fire in His Wake (McSweeney’s). If the story of a desperate community of exiles in Morocco, and their struggle for dignity and a better life, seemed inherently dramatic, my desire to tell it was further emboldened by the unexpected revelation of a close friend in Rabat that he too was a refugee.

Despite my background, I opted for a literary treatment of these events. Not only did the objective, authoritative posture of the reporter leave no room for the contradictions and complexities I wished to explore, but I was also seeking a form of truth-telling that is alien to the world of journalism. As Hannah Arendt has written about the fictional representation of a tragic past, “the story reveals the meaning of what would otherwise remain an intolerable sequence of events.”

This elaboration of a deeper meaning out of a series of “intolerable” events may be what most distinguishes literature from mainstream journalism. The “story” for the journalist is merely the hook. The reporter sallies forth into the field and reports back to the readers—report itself deriving from “re-portare”, literally to “carry back”. By contrast, literary imagination, to paraphrase Nayeri, “teleports” or transports its readers to the site of its telling. The writer directs her gaze far off and conjures a world which is not present into the present. Where journalism seeks to inform, literature seeks to enact.

Nonetheless, for all the potential of fiction to represent a fuller, more meaningful truth, the reporter holds certain advantages over the fiction writer: a more permissive public and wider license to tackle controversial themes. On a daily basis, NGOs implore journalists to report on crimes against humanity. Since the reporter merely carries back a likeness of what has transpired, her action is heroic and her authority (generally) unquestioned. But the contemporary writer who dares imagine such atrocities is a target of suspicion. The legitimacy of her gaze is questioned: “Why are you looking at this? Shouldn’t you stick closer to home?”

Fiction is highly politicized in our day. This is especially true when an author seeks to portray migrants and refugees who, like the men in the photo above, are politicized, oppressed, threatened, and disbelieved. If we sometimes sniff around the edges of a news piece for sensationalism, we regularly stipulate something very special from the author of such works: authenticity.

I am thinking of the recent controversy around Jeanine Cummins’ American Dirt: this much-hyped thriller about the brutal slaying of a Mexican bookseller’s family and her desperate flight to the United States with her son, penned by a white, non-immigrant American. Cummins has been charged with cultural appropriation and capitalizing on immigrant trauma (“trauma porn”), and this has played a part in broader claims of whitewashing in the publishing industry.

Unsurprisingly, Cummins has sought to defend her novel by re-classifying herself—invoking a Puerto-Rican grandmother, a Spanish birthplace, and a newfound self-identification as Latinx. Her cynical biographical shuffling is an intuitive response to a particularly American phenomenon in which origin is a validating precondition for certain literary plots. I am not interested here in evaluating American Dirt, but rather in interrogating the claims of identity and authenticity that have been foisted upon the novel and its author; impositions that are rarely made on journalistic production.

Over 140 prominent writers published an open letter to Oprah Winfrey urging her to rescind American Dirt’s inclusion in her book club. Among the signatories was Mexican author Valeria Luiselli, whose autobiographical novel Lost Children Archive also focuses on the plight of the men, women and children trying to cross the Mexican-American border. Not only does Luiselli’s novel offer a useful foil to American Dirt, but perhaps more than any other contemporary work of fiction, it deftly enacts the divide between literary and journalistic ethics (and ethos), when it comes to representing the victims of structural violence.

On its face, Lost Children Archive recounts a road trip taken by two married journalists and their children from New York City to the Mexican border. The nameless couple are practitioners of a unique school of journalism: they identify as soundscape artists. Whereas the husband is on a mission to record the ghostlike echoes of the last of the Apaches, his wife wishes to document the traumatic traces left by the thousands of children who go missing every year while trying to enter the United States.

The female narrator/wife, like Luiselli herself, at least has the pretext of having volunteered as a translator for child asylum hearings in New York, and one infers that she is Mexican. But what the presumably white, male American protagonist is about, visiting the graves of fallen Apache chiefs and trying to capture the sonic reverberations of the Native American genocide, is never deeply interrogated. Journalists, and by extension, sound engineers, are rarely confronted with accusations of inauthenticity or cultural appropriation. It is assumed that the picture (or the sound) speaks for itself.

The wife at first helpfully, and later begrudgingly, aids the husband with his sound-history of the defunct Native American tribe, but her project, we soon discover, is more literary in bent. Obsessively cribbing notes from Susan Sontag’s diaries, paralyzed by questions of how to “make art with someone else’s suffering,” the narrator finds herself unable to begin writing and grows estranged from her husband, eventually impugning him for “his nasty, guiltless dreams.”

When the narrator learns of a looming deportation flight, the couple speeds across the country to intercept it. They arrive just in time, sound recording gear in hand, but there is no way to approach the airfield. Impotently, they watch a far-off line of children be deported by the border patrol. The narrator wants to reach the children but she is blocked by a high wire fence, at which she kicks with loud imprecations before dissolving into tears.

The scene is both an exteriorization of the narrator’s guilty conscience and a striking metaphor for the serious challenge fiction writers face today. We come to understand that Luiselli herself never makes it beyond that fence. Instead, she writes a novel for the most part confined to her protagonist’s subjectivity.

Lost Children Archive is a work of autofiction that never dares depict the object of its obsessions because it is unsure whether the author has that right. Indeed, what claim does a well-off writer, the daughter of a Mexican diplomat, have to access the inner struggles of these refugee children?

It is from the fiction writer that we want biography—we demand an accident of birth and upbringing to endow the writer’s gaze with authority.

Cummins feels none of these compunctions. She transports the reader on la Bestia, the rumbling network of Mexican freight trains that carry migrants north towards the US border. I can hardly think of a more salient contrast, in regards to the permissibility of literary representation, than Luiselli’s narrator impotently kicking at the fence while a faceless group of children are refouled, and Cummings’ thriller, in which we ride along with mother and child on the perilous train north.

*

There are, nonetheless, more distinguished exponents than Cummins for a daring strain of migrant fiction. Colson Whitehead, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Underground Railroad, has recently emerged as a champion of the writer’s right “to write what you don’t know,” and his fantastical approach to the literature of trauma may offer a middle ground between Luiselli’s austere pieties and Cummins’ privileged insouciance (and clumsy post-facto mea culpas).

“I think it’s one of the jobs of the artist to attack different parts of the world,” Whitehead argued in his keynote address at the 2019 AWP Conference. “No one’s going to call you out if you get it right. They call you out if you fuck it up.”

The Underground Railroad recounts the flight of two refugee slaves via a magical realist network of subterranean trains and the Dantean accumulation of horrors they witness on their way. Tellingly, the novel was also an Oprah Book Club selection and is no less a thriller than American Dirt. Its protagonist, Cora, is hunted by a sadistic slavecatcher named Ridgeway much as Lydia, Cummins’ hero, is pursued by Javier, the caricatural head of a local Mexican drug cartel.

Whitehead has moreover concocted certain scenes, for instance the novel’s nightmarish “Freedom Trail”—in which thousands of tortured, castrated slaves hang from hundreds of miles of trees—that are without historical referent and toy with “trauma fetishization and sensationalization,” the very charges launched against Cummins.

As he admits in his speech, Whitehead grappled for years with his right to fictionally represent the brutal history of American slavery. What justification did a wealthy Manhattanite, whose previous two novels were about a zombie apocalypse and summering in the Hamptons as a teenager, have to claim this past, even if he happened to be African-American?

I suspect this is why Whitehead swapped out the historical underground railroad for a conspicuous fantasy: an oneiric network of tunnels and tracks, winding for thousands of miles beneath the American South, with a band of whimsical conductors and station-masters. Whitehead opted for a twist that pointed to the fictiveness of his fiction. He wanted to remind the reader that, like Luiselli, he was looking at these horrors from behind a fence.

Such a self-conscious subversion of a narrative’s own historical authority flies in the face of the conventions of mainstream journalism. This is especially true for visual journalism, which tries at all times to camouflage the fence (the camera) that stands between the journalist and the “subject.” The camera claims to have been there. But where is there? It could easily have been behind a fence—you have no way of knowing how long the lens was that took the photo above.

The journalist claims authority by virtue of her presence onsite. It is assumed that she stands inside the fence, and the challenges posed to her are rarely about her right to tell a story. Instead, they concern objectivity and veracity—did the journalist allow all the participants to have a voice? Did she relate the events without a hidden agenda, blindness or prejudice?

It is from the fiction writer that we want biography—we demand an accident of birth and upbringing to endow the writer’s gaze with authority, even when “fiction” is grandly stamped on the cover. I would like to believe that The Underground Railroad received less nervous scrutiny than American Dirt because of its exuberant foregrounding of the fictiveness of its plot, and not simply because its author is African-American whereas Cummins was white.

But this too may be a fiction. If so, it would mean that we have confined certain writers behind an invisible fence, and like the narrator of Luiselli’s novel, they may no longer see a way to tell certain tales.

No one challenged my journalistic authority to record the men depicted in the photo above, or asked whether the photo amounted to cultural appropriation (much as I hardly had to justify my right to sit, eat, and spend time with them). Like the husband in Lost Children Archive, I might edit a reportage about them with hardly a qualm, but like the wife, I would be hesitant to fictionally represent them. The literary act, at least in modern times, requires some sort of “connection”—cultural, ethnic, historical—to abet its daring imagination. The writer today who “attacks other parts of the world,” is greeted like a burglar, caught crawling out of a window with the family jewels.

But the photo above has also been burgled. The reporter takes it and carries it back to the public with their implicit sanction. The fiction writer, racked by guilt, stays behind.

Where the men in the photo are now, I can only imagine.

I hope I have that right.

__________________________________

Spencer Woolf’s novel The Fire in His Wake will be published on June 23rd, 2020.

Spencer Wolff

Spencer Wolff is an award-winning documentary filmmaker and journalist based in Paris, France. His work focuses primarily on diaspora, migration and racial justice and has previously appeared in The Guardian, The New York Times and Time, among others. An adjunct faculty member at the École normale supérieure (Paris), he is a graduate of Harvard College, Yale University (Ph.D., literature), and Columbia Law School (J.D.). In 2009, he worked at the UN Refugee Bureau (UNHCR) in Rabat, Morocco. The Fire in His Wake (McSweeney’s) is his first novel.