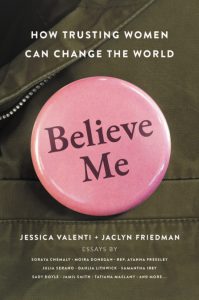

What if we believed women? That’s the question at the heart of the new anthology Believe Me, edited by Jaclyn Friedman and Jessica Valenti which gathers together more than two-dozen leading voices on gender, power, and the most pressing issues shaping feminism today. Among them are Dahlia Lithwick and Moira Donegan, who came together for a conversation on the ways in which institutions are ill-equipped to address violence against women along with the systemic failures on display during the Kavanaugh hearings in 2018.

*

Dahlia Lithwick: Hi Moira. I loved your essay on the way early psychoanalysis failed to address women’s trauma but it also broke my heart a bit. The parallel narratives of Dr. Freud attempting to talk truthfully about women and sexual assault and then being forced to retract it to save his career, while Bertha Pappenheim had to save herself by escaping the world of men and building a life in feminist advocacy and organizing, feels all too contemporary to me; you can pass in a man’s world or you can be full throated in a woman’s world, but never dare to hope for more.

In my essay I tried to get at the ways in which the machinery of our ostensibly neutral justice system is propped up by the machinery of agents, lobbyists, pricey attorneys, and all the things that mean—to paraphrase our colleague Irin Carmon—that the system is in the room, toiling at great expense to press and defend the narrative you depict as “the rapist as an upstanding man, their memory of the past as happy or peaceful.” I wonder what you think about what happens when women in mainstream media are essentially forced to choose between Pappenheim’s lane and Freud’s? We can try to forge through the turgid he says/she says conventions, or we can try to invent new forms with which to do journalism. Are we making any headway, covering abuse and assault in the mainstream press? And are we taking care of ourselves as we do the work?

Moira Donegan: Hi Dahlia. Thanks so much for your piece, and for your work covering those horrible hearings. I felt so much rage on your behalf, and on Dr. Blasey Ford’s behalf—rage at the humiliation of her and all those other women in the room, and rage, too, at the phenomenon that your essay so perfectly captures: that maddening gap between what happened and what an institution can be made to respond to.

I think there is a growing sense that appeals to institutions to deal with sexual violence—institutions like the criminal justice system, a human resources department, or, say, the Senate judiciary committee—are futile, and tend to backfire against women. It’s not just that these are he-said she-said debates, since, as your essay points out in the beginning, they often really aren’t. But there’s also the messy reality that the framing of sexual assault testimonies as he-said, she-said conflicts is very convenient for men in a context where what he said is always given more weight, where men’s words and men’s lives matter more than women’s. Credibility, belief—these are moral commodities whose distribution is deeply political. Men are believed more in institutional settings, because it is convenient to power to believe men more. That’s true even when what men say has little relation to fact.

Outside of the institutions that are dominated by men, women are able to speak the truths that male power finds inconvenient.It’s hard not to be cynical about the possibilities for justice when you’ve seen justice thwarted so many times. I was really heartbroken by your description of that moment after Dr. Blasey Ford testified and before her attacker did, that moment of deranged, almost manic hope that Dr. Blasey Ford had managed to force an institutional response. I had that moment of wild hope too, covering that hearing from my couch, with the laptop perched on my knees. It seemed inevitable that something would change. And then it didn’t.

DL: I agree absolutely. And journalism, just like those other institutions you describe, needs to decide whether it wants to do more of the same, or to radically reform itself to take womens’ stories on their own terms. You, of all people, have seen the consequences of the choice to stay the course. But like your Freud and Pappenheim, it cannot continue to be the case that there is mainstream journalism and a side of #MeToo. I think #MeToo initially started as a rejection of mainstream journalistic norms, right? It started on social media, perfectly democratized and away from the obligations (and legal liabilities) of a mainstream press that is crafted to—and still largely devoted to—protecting wealthy predators. (See, e.g. Ronan Farrow’s work on this).

The fact that 80 women leveled credible accusations against Harvey Weinstein and he may yet escape liability tells you all you need to know about the inadequacy of the modern legal system and even the mainstream media to redress the kinds of violence and abuse that Hollywood, the courts, journalism, academia, and virtually every other profession have condoned and covered. The internet and feminist twitter have served as a kind of corrective to that, but not really, and the prevalence of the Epsteins, Weinsteins and Kavanaughs suggests that even if stories are told they may not change the final outcome. Where else do you locate hope for a rejiggering of how the Bertha Pappenheims find homes for their trauma?

MD: I agree with your assertion that information is freer on social media, where it is (mostly) removed from institutional constraints like legal liability, or the friendships and biases of male editors. This kind of extra-institutional, semi-clandestine conversation that you see online has always been a huge part of feminist history. Think of the consciousness raising groups where women shared their experiences of sexism during the feminist Second Wave. Or think of the whisper network, where conversations that to the outside world get trivialized as gossip take on the purpose of mutual aid. In informal settings, outside of the institutions that are dominated by men, women are able to speak the truths that male power finds inconvenient.

In my essay, I looked at two different responses to the realization of how pandemic sexual abuse is and how unwilling mainstream institutions are to address it. Sigmund Freud saw institutional unwillingness to grapple with sexual violence and capitulated to it: he decided that if the mainstream decided that sexual violence wasn’t a problem, he wouldn’t treat it as a problem, either. His patient Bertha Pappenheim, also known as Anna O., made a different choice: she turned away from the mainstream that denied her experience and devoted much of the rest of her life to helping other women. I might push back a bit on the notion that in her feminist work Pappenheim was somehow turning away from public life. What she was turning away from was male rule, male priorities, what Andrea Dworkin called “male law.” I like that qualifier, how provocative it is: not the law, male law.

A lot of power is vested in these institutions that deny women’s experience of sexual violence, and I don’t want to deny that. But at the same time, those institutions are not the totality of the world. The real world is also the conversations that women have together that don’t get validated by The New York Times or the Washington Post. The real world is also the rooms where women sit and talk about their own experiences. The real world is also what women say to each other and do for one another when there are no men in the room.

DL: And that takes us back to that Margaret Atwood line right? That women are afraid men will kill them and men are afraid that women will laugh at them? Somehow you and I both seized on that line from Dr. Blasey Ford about how the laughter of her assailants was indelible in her hippocampus. It’s always the laughter. Remember when Kavanaugh was done testifying and Trump brought a whole rally to tearful laughter when he mocked Dr. Ford? The laughter of exonerated predators must be the greatest sign of privilege I can imagine. Anger is the easy reaction, it seeks to punish and push down, but laughter seeks to erase and belittle. It says: You are an object of laughter because you don’t even matter enough to be taken seriously. Moira, I used that sentence in my essay precisely because Dr. Blasey Ford’s use of it highlighted her erasure at the time of the assault and because it grabbed us by the throat to hear that she carried that laughter as a scar decades later. What did it signify to you?

MD: God that moment was devastating. What struck me was that the subject of Dr. Blasey Ford’s expertise was exactly the subject on which her own capacity was being denied: cognition, memory. The Republican senators were asserting that she didn’t remember what happened to her, something few of them seemed to really believe anyway, but which was also a denial of such a remedial function of subjectivity: Do you really know what happened to you, do you really remember who that was. Not only was she an extremely capable knower, but she was also intimately acquainted with the mechanics of that knowing. She’s a psychologist. She said indelible in the hippocampus.

But aside from just that wild denial of her extremely obvious epistemic faculties, I was struck, too, by the contempt of the laughter, the realization she had that her humiliation, her pain, and her comparative powerlessness in that situation was the very thing that was joining the boys together and giving them pleasure. There’s a sadism in that laughter that haunts me.

DL: Yes, we are in a moment of sadism just now, that’s the right word; a visceral delight in the suffering of those we hate. And maybe the whole notion of the anthology—what if we believed women—demands a reckoning with the actual sadism that reduces your Bertha to a case study and my Blasey Ford to a punchline. I’m not super confident that the media or the courts want to really reckon with suffering, not from an evidentiary perspective; we could surely do this better, but from a power perspective. Acknowledging the suffering of anyone other than the most wealthy and powerful at this moment seems to require more empathy than anyone can muster. It’s not just a systems failure. It’s a humanity failure.

__________________________________

Believe Me, edited by Jessica Valenti and Jaclyn Friedman, is out now via Seal Press.