We are having a picnic by the Avon, Dad, me, Jonathan, and both pairs of dogs, his and ours. Jonathan and I are swimming, Dad is sitting on a camp chair watching. We are floating flat, spreadeagle in the water holding onto the river weed; the river is fast and if we let go it takes all our strength to remain swimming in the same place. We dive down, I open my eyes under water to see the blur of long horsetails of iridescent green. And then I look up to see the blurred shape of Dad at the edge of the bank at a forty-degree angle. Dad is in his underwear, up to his calves in mud, trying to get in.

‘Dad, no!’

We quickly clamber out.

‘Dad! Be careful! The current is too strong.’

‘Is it?’ he asks crestfallen. He has seen our pleasure and wants it.

‘Yes.’

‘Yes,’ he repeats after me.

Dad will never lose Yes. Yes, I can. Yes, we will! Yes, of course I can, you tell me when. Yes! Yes, and thank you. Thank you, darling. Thank you! He is the best thank-you sayer in the world. And predictably it is the next thing he says.

‘Thank you.’

* * * *

It is the end of the hot dry summer of 1976. I have flopped my A levels; home life is terrible without Dad; my boyfriend is a year in at Oxford, and I know I am not going to get to university with my lousy grades. I am desperate to get away. I don’t just want to leave home, I want to leave the country. So I get a job behind the bar at the Rising Sun in Warsash, pulling pints and playing darts, until I have enough money for a one-way ticket to Toronto. Toronto, because I have an address there and it makes the leap a little less daunting. I catch a train to London to tell Dad. I am apprehensive because he has spent a lot of time writing letters and pulling strings to find me a place at college, any college, and Oxford Polytechnic have eventually offered me a place to study history of art.

He meets me at Waterloo in the Dormobile. We sit on the bench seats opposite each other in the back. ‘Right, tell me,’ he says. I say I am not going to college, but flying to North America instead. There is a brief computing moment, a flicker across his face, and then he laughs. He roars with laughter. He slots in the table and gets out a box of wine. He says whenever one has a choice, one should always take the most difficult option, because that must be the thing you really want to do–or it wouldn’t have come up as an option in the first place. Then he hunts around for a sheet of paper and writes down a name, address and telephone number, with a note to go with it, which I am to use when I get to America if I ever need help.

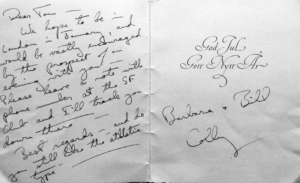

‘Who’s . . . Bill Colby?’ I ask.

He laughs, he already knows I am not going to believe him. ‘He’s the head of the CIA.’

Of course I interrogate him. He tells me they were friends in the war; Dad says he liked to take his money at poker and thrash him at chess. What he didn’t explain was that they trained as Jedburghs together at Milton Hall. I am stunned Dad knows anyone in the CIA, let alone its director, but I am also a little chilled by it.

And so off I set on my beginning-to-regret-I’d-ever-mentioned-it adventure with Dad’s note and a letter from Colby tucked in my passport, and I almost forgot about it. It was December and bitterly cold. I had met up with my friend Ian, and we decided to hitch south and got as far as Louisville, Kentucky.

Our last ride had dropped us off at the edge of town, so we had to walk into Louisville in our Millets boots under our heavy rucksacks (mine–Dad’s 1950s canvas army regulation), looking lost and for somewhere cheap to stay, when a man in a pickup pulled over and asked if we needed help. These friendly Americans. We eagerly explained our predicament. The man said he knew a good budget hotel and offered to drive us there. How kind and helpful we thought. We threw our rucksacks in the back and hopped in. It was disconcerting to turn off the main highway and be heading further and further into a down-and-out neighbourhood, but our new friend was insisting we first go back to his place to meet his folks and have a cup of tea. It was disconcerting, but we didn’t want to be impolite, so we sat meekly looking out the window as we drove into no-man’s-land, past houses with doors boarded up and the windows broken, and abandoned cars with flat tyres slumped half off the kerb, until we pulled up outside his place, a semi-derelict house in a semi-derelict street. It was disconcerting, but we didn’t want to be impolite, so we sat at the crash-site of his kitchen table making small talk, waiting for our cup of tea and his folks . . . for an interminably long time. Until there was nothing left to say and still no sign of tea. Our friend had become nervous and fidgety. Then another man showed up. He didn’t look so friendly. There was that sinking feeling when you know you’re in the shit. We got up to leave. An arm sprang out to block our passage to the door. They wanted our money. Of course they did.

Ian stood his ground, astonishingly in my view, considering we were in their house behind a locked door, and demanded they let us pass. The two men smiled curiously. I gripped the shoulder straps of my rucksack tightly, then suddenly remembered the note. I told them my dad was a very close friend of the head of the CIA, and I had his name and address in my pocket and if anything happened to me I didn’t think he would be too happy about it . . . I waved the letter from Colby to Dad and the two men exchanged glances. An unsure look that flickered back and forth as if there was a faulty light switch. There we stood, by the door in the hall, Ian firmly holding his ground, me holding the letter . . . their predicament teetering in a damp spark in their brains, and then they laughed, said they were only joking and moved aside.

We pushed through, and were back outside in the sun-bright derelict street, but the story doesn’t end there . . . No, for even more bizarrely, now I look back, than going to tea in the first place, is what happened next. The man who gave us the lift followed us out of the house, blaming everything on the other guy, and insisting he drive us to the cheap hotel for the sake of no bad feeling. And being so far out of town and in the middle of nowhere with no means of getting anywhere, we let him! We did. As splutteringly incredible as that may sound. And he did drop us off at a cheap hotel. A real dive: rooms with large beds and broken mirrors, swagged in drapes of cheap crimson velveteen. It was a noisy night of knocking and banging, and people thumping up and down the stairs. The hotel turned out to be a whorehouse for paraplegics and one-legged men–which I only understood the next morning when Ian explained why there were so many paraplegics and one-legged men in reception at checkout.

I still have the letter from Colby to Dad. ‘If your daughter does indeed come this way, please have her look us up as we would be happy to have a renewed contact with the Carew clan.’ It seems inconceivable now, not to have taken up an invitation to visit the last of the great spy-masters. At nineteen, friends of one’s parents only cramp one’s style.

* * * *

Bill Colby’s leadership of the CIA began towards the end of Vietnam, and finished in the middle of Watergate. It was a tumultuous tenure during which Colby compiled and released a notorious set of reports known as the Family Jewels. The Family Jewels detailed the controversial activities of the CIA between the 1950s and mid-1970s. Colby called them the skeletons in the CIA closet. These skeletons included the CIA’s illegal wiretapping; assassination plots; and the many crazy attempts to kill or discredit Fidel Castro–including exploding cigars, poison pens, a chemical that would make his hair and beard fall off, infecting his diving suit with deadly fungus, and a plan to administer LSD before a public speech. The agency’s widespread sabotage in Cuba was manic and endless: sugar contamination, turkeys infected with fatal viruses, pigs infected with swine fever, swarms of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes set loose carrying dengue fever, anti-crop warfare, chemicals added to lubricating fluids which caused premature wear on engines (one West German company was even paid to manufacture ball bearings off centre). Added to this litany was the CIA’s widespread domestic surveillance and the extremely dubious cases of non-consensual human experimentation. Of these, one of the most sinister was the case of the ‘cursed’ bread of Pont-Saint-Esprit in southern France. A mass outbreak of hallucinations in 1951 was put down to the presence of a psychedelic ergot mould at the local bakery, but later was revealed to be LSD administered to the unsuspecting town as part of a mind control ‘field experiment’ by the CIA. One man tried to drown himself screaming his belly was being eaten by snakes; another leapt out of a second-floor window shouting, ‘I am a plane!’ while an eleven-year-old tried to strangle his grandmother. Five died and dozens of others were taken to the asylum in straitjackets. The code name for this human experimentation programme was MKULTRA. MKULTRA recruited former Nazi scientists prosecuted in Nuremberg with experience in various brainwashing techniques and torture. Hypnosis and personality types susceptible to hypnosis were also studied by the CIA with experiments in anterograde and retrograde amnesia. Derren Brown explored this subject head-on in his TV series The Experiments in the episode ‘The Assassin’–the one where Brown hypnotises an unwitting (but previously gauged susceptible) member of the public to shoot Stephen Fry (in a packed theatre without knowing his gun was loaded with blanks) to demonstrate the very real possibility of hypnosis having been used to persuade Sirhan Sirhan, a twenty-four-year-old Palestinian refugee (and unlikely assailant), to assassinate Bobby Kennedy on 6 June 1968. Sirhan has been denied parole because he can feel no remorse for something he has no memory of doing. Is Sirhan a real Manchurian Candidate? Derren Brown seems to think he could be. After watching the rigorous step-by-step planning of Brown’s terrifying programme, so do I . . .

The commissioning of these shaming reports about the activities of the CIA (that violated its charter) was a response to press reports of CIA involvement in Watergate. Bill Colby testified before congressional committees fifty-six times, giving straight answers when many believed it was his duty to lie. He co-operated with Congress to demonstrate the CIA was accountable to the terms of the Constitution, but also because he’d weighed up the pros and cons and judged the revelations would do the agency no long-term harm. Details of the contents steadily dripped out, but full public access was denied until 25 June 2007, when the papers marked SECRET EYES ONLY were released, albeit heavily redacted.

Colby in many respects was a liberal; he became a supporter of the nuclear freeze and reductions in military spending which, together with his controversial openness policy, caused a major rift within the ranks of the CIA. By the time I was in America on my little jaunt in 1976, he had more enemies than friends, including Gerald Ford and Henry Kissinger. In what was known as the Halloween Massacre, Colby was replaced by George Bush senior; Kissinger was fired as National Security Advisor; and James Schlesinger, the Secretary of Defense, was replaced by Donald Rumsfeld. In a chequered career, with a trolleyload of controversies surrounding him (not least his role in the Vietnam war, in which the CIA was reputedly engaged in the torturing and/or neutralising of 81,000 Viet Cong supporters), the final and most perplexing one was how Bill Colby died.

The scene is Colby’s house in Maryland, a turn-of-the-century oysterman’s cottage on Rock Point surrounded by water on three sides with a spectacular view across Neale Sound, up the Wicomico River and over to Cobb Island where Colby kept his boat. According to former Time journalist Zalin Grant his home was unpretentious, tranquil and anonymous. Which is just how Dad described Colby. On 27 April 1996, Bill Colby rang his wife to say he was going home to eat dinner, have a shower then head to bed. The following day his submerged canoe was discovered in the river with a tow rope still attached. Colby had been missing for eight days when his body was discovered forty metres from the canoe. The official autopsy concluded he had had a heart attack or stroke, fallen from his canoe, and died of hypothermia and drowning.

Dad didn’t believe it. None of the Jeds believed it. They knew Colby, and nothing added up. They weren’t the only ones. His neighbours were sceptical he would have gone canoeing that late, the wind was up, the water was choppy, and he was a prudent man. The last person to speak to him was his caretaker at about 7.15 p.m. who said Colby was watering his trees because he was due to return to Washington the next day. The man who found his canoe said it was full of sand, yet it was impossible for only two tides to fill it up to that extent. His shoes were off and there were no paddles or life jackets anywhere to be found. Yet he always took out a life jacket. Back at Colby’s unlocked house, the radio and his computer were on. His keys and wallet were on the table. His favourite meal of clams was abandoned half-eaten on his plate, a glass of wine on the counter and a clutter of saucepans in the sink. Yet, Dad said he was a fastidious, meticulous man. He would never have gone out leaving the house open or untidy in such a way. Fellow Jed Dick Rubinstein wrote to Dad: ‘Why a canoe trip in fairly rough weather, in the dark and with the computer running and the meal not cleared away?’ Why indeed? Why would anyone leave in the middle of dinner and go out in a canoe in darkness? The massive search for him with helicopters, divers, volunteers, sonars and draglines went on for eight days and nights, yet he was recovered from marshes that had been searched numerous times, as if he’d just been tossed in.

There were many conspiracy theories; the Sun even ran the headline: ‘Dead CIA Chief Was Set to Finally Blow Lid on JFK Assassination’. Whatever/whoever it was, after a long clandestine career that began as a Jedburgh at Milton Hall, in the end it turned out Colby couldn’t save his own skin, but I have a strong suspicion he might have saved mine, one nondescript evening in a semi-boarded-up street in Louisville in 1976.

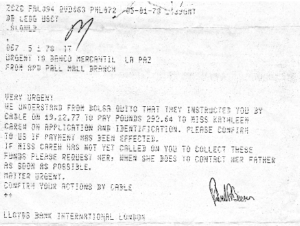

Cable to Bolivia, 5 January 1978, 19.39 GMT: URGENT TO BANCO MERCANTIL LA PAZ FROM APD PALL MALL BRANCH:

I was off the radar and Dad was looking for me. I had been gone over a year edging my way further south, four months working illegally with Mexicans in a cotton gin (where raw cotton is processed) at a place called Sweetwater in the heart of Texas (ninety hours a week, $2 an hour, time and a half overtime), then on the road, deeper into the Americas, until my money ran out. By the time Dad was trying to find me I was halfway down South America travelling by local bus. Stapled to Dad’s cable is a sheet of graph paper bearing a list of questions in his handwriting (red biro) to Rikki Gilbert Rolfe (Dad’s accountant at Percy Coutts); with Rikki’s reply in blue, down the right.

From DADLAND. Used with permission of Grove Atlantic. Copyright © 2017 by Keggie Carew.