Czesław Miłosz Confronts the Dark and Immutable Order of the World

From the Russian Empire to the Republic of Letters

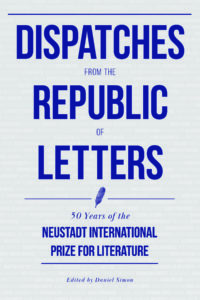

When Czesław Miłosz (1911–2004) visited the University of Oklahoma in April 1978 to be honored as the fifth laureate of the Neustadt International Prize for Literature, he marveled over the improbability of it all: “The Neustadt literary prize belongs too, in my opinion, to those things which should not exist, because they are against the dark and immutable order of the world. . . . The decision of founding such a prize seems to me a wise one, not only because I am a recipient, but because it favors all those who in the game of life bet on improbability.” Miłosz’s acceptance speech, along with Joseph Brodsky’s nominating statement that championed Miłosz for the prize that spring, will be reprinted in Dispatches from the Republic of Letters: 50 Years of the Neustadt International Prize for Literature, forthcoming from Deep Vellum Publishing on October 19. The anthology, edited by World Literature Today’s current editor in chief, Daniel Simon, gathers the acceptance speeches by the first 25 laureates of the prize since 1970 along with tributes by the jurors who nominated them.

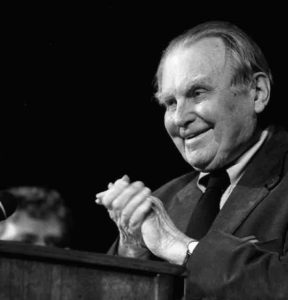

Czesław Miłosz receiving the 1978 Neustadt Prize at the University of Oklahoma; courtesy World Literature Today

Czesław Miłosz receiving the 1978 Neustadt Prize at the University of Oklahoma; courtesy World Literature Today

*

One of the essential attributes of poetry is its ability to give affirmation to things of this world. And I think with sadness of the negation which has so strongly marked the poetry of my century and my own poetry. When our historical and individual existence is filled with horror and suffering, we tend to see the world as a tangle of dark, indifferent forces. And yet human greatness and goodness and virtue have always been intervening in that life which I lived, and my writings have some merits to the extent that they are not deprived of a feeling of gratitude.

Logically, I should not have preserved my identity as a poet faithful to his native tongue throughout thirty years of exile. I explain it by a mysterious influence of a land where I was born, Lithuania, and of a city where I went to school and to university, Wilno. My high school teachers have been present in my poetry, either invoked by name or as invisible guests. It is probable that I would not have become a poet without what I received from them. Particularly, I was shaped by seven years of Latin and by exercises in translating Latin poetry in class. If the names of those teachers are forgotten, I, for one, remain their grateful pupil.

For many years I have been meditating upon zones of silence covering many events, deeds and names of our age. To quote myself: “I would have related, had I known how, everything which a single memory can gather in praise of men.” Had I known how 3/4 in fact, writing praise is a struggle against the main current of modern literature. But now, in the last quarter of the twentieth century, looking back to the time of war and political terror, I think less of crime and baseness and more and more of human capability of the purest love and sacrifice. Had I to live much longer, I would search for means of expressing my humble respect for so many anonymous and heroic men and women.

Logically, I should not have preserved my identity as a poet faithful to his native tongue throughout thirty years of exile.

The Neustadt literary prize belongs too, in my opinion, to those things which should not exist, because they are against the dark and immutable order of the world. Normally, it should be given to film stars or at least authors of best sellers. In my case it goes to a poet who can be read only in translation and whose poems do not translate well because of many cultural-linguistic allusions in their very texture. It goes to an author who, measured by the market standard, is a permanent flop and is read by a very small public only. The decision of founding such a prize seems to me a wise one, not only because I am a recipient, but because it favors all those who in the game of life bet on improbability.

The endeavors of Ivar Ivask are an example of human will interceding against the normal and the usual. There is no reason for survival of such a magazine as World Literature Today and no reason for the University of Oklahoma’s attracting the attention of literary communities all over the world, as it does, because of that periodical and an international prize. Yet the order of the world has to inscribe that fact as one of its components.

Norman, Oklahoma

April 7, 1978

__________________________________

From Dispatches from the Republic of Letters: 50 Years of the Neustadt International Prize for Literature, 1970–2020, edited by Daniel Simon (Dallas: Deep Vellum / Phoneme Media, 2020). Excerpted by permission of World Literature Today.

Czesław Miłosz

Czesław Miłosz (1911–2004) was a poet, writer, and translator born in the village of Szetejnie in a district that today is part of Lithuania. His first book of poetry was published in 1934. After World War II, which he spent in Warsaw, Miłosz defected to Paris in 1951, and the Communist government of Poland banned his works. In 1960 he immigrated to the United States, where he began teaching at the University of California at Berkeley. It was not until the Iron Curtain fell that Miłosz was able to return to Poland, and he split the remaining years of his life between Poland and the United States. Miłosz’s Selected and Last Poems, 1931–2004 (Ecco Press), selected by Robert Hass and Anthony Milosz, were published in 2011. Two years after receiving the Neustadt Prize, Miłosz received the Nobel Prize in Literature.