“Cut, Cut, Cut, Until the Spirit Shines Through.” Sarah Ruhl on Craft and Catharsis

The Author of Smile in Conversation With Playwright, Beth Henley

Photo by Gregory Costanzo.

Two decades I met one of my literary heroes, Beth Henley, at a writer’s retreat in Princeton, hosted by the McCarter theater. There she was, wearing a floppy hat, under a tree with a notebook. She was a hero of mine, and I couldn’t believe that there she was, in the flesh. We became friendly, and Beth, learning that I was terrified of moving to Los Angeles to follow my now-husband and that I didn’t know a soul, became a constant source of solace, literary and human, in a foreign city. We went to each other’s openings, cheered each other on, talked about motherhood and its trials, and drank with each other after galling first previews. Our conversations about life and literature have been on-going for the last twenty years.

–Sarah Ruhl

*

Beth Henley: What are some ways you live your life for Sarah Ruhl, the artist versus the person? Is it all one?

Sarah Ruhl: I think it’s all one, isn’t it? If I tried to pull it apart, the writing life versus the life-life, I think it would all go pear shaped. I could imagine it being “healthier” to divide the two—the writing life and life-life, and to be workmanlike about the whole enterprise—but I can’t. It would be like telling your skin that it was separate from your hand. And on one level, I suppose the skin is not the hand. If you bruise the skin, the bones still work. Do you divide up the artist life from the person life?

BH: I believe if you are an artist then the artist’s life is your life. But maybe there is no such thing as an artist if there is no such thing as a self.

SR: Beth, that is so Zen I need to sit in silence and think about that for 45 minutes.

BH: When you begin a project how much are you focused on craft versus inspiration?

SR: I don’t know a thing, consciously that is, about craft. I don’t know about craft for writing, and I don’t know about craft as in “craft” either. My daughters are amazing knitters, so is my mother. The craft gene apparently skipped my generation. Give yarn to my sister or to me and it will stay in a little heap on the floor. I see those patterns and my brain goes sideways and my hands stumble around with tangled thread. So the word craft reminds me of knitting, something I’m hopeless at. I am sure that I do have some writing craft, but I don’t know how to identify it.

“If you are an artist then the artist’s life is your life. But maybe there is no such thing as an artist if there is no such thing as a self.”

BH: When you are working on a play, book, or screenplay, do you find there are some things you avoid reading?

SR: I avoid anything so close to my topic as to slow me down. I love reading non-fiction and poetry while I’m writing anything else. When I’m reading a novel, and really immersed, it’s my whole world, so I couldn’t possibly write while I’m deeply inside of one. I disappear. Like when I recently read Pachinko, or My Brilliant Friend, I was gone for a week. Ask my children or husband. They were like, “Uh, where are you?”

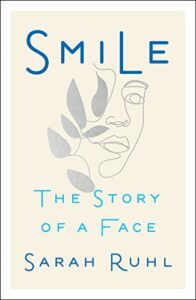

BH: Your new book is called Smile: The Story of a Face. What did your children say when you told them you were writing a book about your crooked smile and lizard eye?

SR: They laughed of course. And said, “why would you write about that?!” Lizard eye comes from my son William misunderstanding me when I referred to my “Little eye.” With Bell’s palsy, the condition I’ve had for ten years, the muscles sometimes grow back incorrectly, giving you a condition called synkinesis. In my case, my left eye closes a bit or gets smaller when I try to smile. So William heard me talk about my “little eye” but he thought I was saying “lizard eye” all this time and he thought it was hilarious. Thank God our children laugh at us. And thank God they love us unconditionally.

For example, Anna recently overheard a conversation I was having with my editor about the book, she said afterwards, “I’ve always imagined your face as a beautiful house. And one day one of the walls suddenly fell down. And you spent all this time trying to build it back up, brick by brick, and you couldn’t quite. But when we look at your face, all we see is our house.” I was so moved by her response. I thought, if I’d known that ten years ago, maybe I wouldn’t have had to write a book about it!

BH: The book is wide, wide in its scope: all the arts and sciences, philosophy, psychology, anthropology, diagnosis, feminism, family, death, illness, pregnancy, marriage, motherhood, tragedy, friendship, and it is hilarious, which makes it bearable when that seems impossible.

SR: I love that. We need hilarity to make things bearable. And you are a master of that, Beth. You are a role model. Your work walks that razor’s edge between laughing and crying.

BH: Thank you. Speaking of crying, the story of your father, your relationship, his illness, his death your grief was layered throughout the book brilliantly. I felt like he was riding in the boat of the book. This is not a question just want to tell you how I was riveted and torn apart. For both of you.

SR: Yes. He’s always riding on the boat. Or I hope he is. That’s such a beautiful description. My friend, the playwright David Adjmi, says my father is in everything I write. It’s sort of like finding the hidden Nina in those drawings by Al Hirschfeld. Apparently after Hirschfeld’s daughter’s birth he hid her name in every drawing. I always loved looking for those hidden Nina’s as a child, sometimes with my father, who is probably the one who told me that story. I guess I don’t really hide my father’s name in this particular book, he is very much there.

BH: What part of the book were you most afraid to write?

SR: I was probably most afraid to write the section where I sort of fell apart postpartum and left the house like a human non-sequitur and wandered around Brooklyn looking for a kayak at night. I was afraid of revealing that. And here I am revealing it again. I think postpartum issues are so hard to talk about because there is very little language for those blurry times, and I think there’s a stigma, not only an external one, but an internal stigma too—a deep shame. The thinking goes something like: if you’re depressed after having children, it means something about your ability to mother, or love. When in fact it has nothing to do with your love. And everything to do with hormones and a lack of sleep. How did you cope with writing and motherhood when your son Patrick was little?

BH: I didn’t cope well. I was terrified. He cried a lot. I couldn’t breast feed and wanted to die. Insanely I went to the previews and opening of a play of mine in London when Patrick was three and a half weeks old. Maybe it was months? I was in a delusional state. Okay, more thoughts: How did you maintain such a high level of work? Even if you lived a perfectly healthy life on an island, the beauty and quality of your work in those years is astonishing.

“Postpartum issues are so hard to talk about because there is very little language for those blurry times, and I think there’s a stigma, not only an external one, but an internal stigma too—a deep shame.”

SR: Oh, God. That’s nice of you to say. I think I had a trifecta prodding me on and that was: knowing that if I didn’t write I would really fall apart, otherwise known as stubbornness; second, my husband; third, my babysitter. I can’t say that I would have made it through without them. Tony (my husband) would arrange things domestically so that I could write. He knows me deeply and knows that if I don’t write, I’m not myself. He tried to make a structure for me so that I could be myself. Thank God for Tony.

BH: Thank God for Tony.

SR: I also think, as a culture, we don’t acknowledge our babysitters enough in terms of working mothers’ ability to function. That kind of care is like some invisible afterthought in the narrative of a writer’s life. For me, our baby-sitter Yangzom was no afterthought but honestly indispensable to my writing life, and, as it turns out, to my spiritual life. She taught me about Tibetan Buddhism, both in what she said and how she moves through the world. That’s another thing that got me through—meditation and constantly reading Buddhist texts. Didn’t you also have a baby-sitter who was a force for good in the world and allowed you to write as a single mother?

BH: Yes, I had two great women helping me take care of Patrick. Rosa Hosmer and Vangie Freeman. They saved Patrick’s life and mine. Rosa left when Patrick was 13 and Vangie stayed until she died of cancer 3 years ago.

SR: I find that these people who allow other mothers to write, or do other work that they do, are so often invisible in the writing itself. And yet, without them . . . Big Silences.

[Big silence.]

BH: One question for me. Could you illuminate the role religion, faith and spiritual yearning played in your recovery?

SR: Yes, that’s a big one. I was raised Catholic but lost faith in the institution at a point. But I find the form of prayer often returns to one’s roots in a crisis. I remember Flannery O’Connor’s (Catholic) prayer journal, where she writes, “My dear God…it takes no supernatural grace to ask for what one wants and I have asked…but I don’t want to overemphasize this angle of my prayers…I have been reading Mr. Kafka and I feel his problem of getting grace.” This problem of “getting grace” when it’s supposed to come unbidden—it’s a real tangle. In my case, I had lost my smile and wanted it back, but I was too Catholic to ask for it. The book Smile is, in a way, a pilgrim’s progress from no smile to partial smile, and from Catholicism to Buddhism. I learned a great deal about stillness and acceptance and regeneration along the way.

BH: One of the hardest parts of the book for me was when you had to be on bedrest with the itching disease that could kill your twins. There is no full recovery from that experience and that was before Bell’s palsy! I dissolved when I read about the agony, shame, rage, isolation you suffered with Bell’s. The clarity and honesty with which you explored your hidden self was cathartic. So, yes, your book is cathartic, kind of sneak cathartic.

SR: I love the term “sneak cathartic”. It turns out that it was sneak cathartic for me to write. I didn’t know it would be until I was sobbing on Jessica Hecht’s bed (she wasn’t there, she loaned me her house in Williamstown to work on the book) while I was writing the last pages. It turns out that writing the book was the missing piece for me in terms of healing. Of course it was, I’m a writer goddammit, but I didn’t know writing about Bell’s palsy would help me heal from it. I’ve often wondered how you had the stamina to write after some tragic events in your life. Can you speak to writerly stamina? Stamina after tragedy?

BH: Stamina and tragedy. After my nephew was killed, I wrote about it with numb voraciousness. After my mother was killed, I went to Christopher Reeve’s website over and over. I read about how he was dealing with paralysis. Once he moved a finger.

SR: That’s incredible. It’s incredible how other stories of endurance help us when we think we cannot go on.

BH: I love what you say about disappointment versus tragedy in the book. It occurs to me that tragedy is often preceded by disappointments. The student’s grades are disappointing. Then the student jumps out the dorm window, causing tragedy. On the other hand—and with you there always seems to be catharsis—disappointment can precede catharsis.

SR: I think ultimately it was incredibly cathartic for me to write the book, and I hope it provides catharsis for readers. I do think the writer is the first reader of her book, and so if the writer surprises herself, hopefully the reader is surprised. If the writer bores herself, so too the reader. I suppose this algorithm does not always work, but if the writer learns and grows, one hopes that comes through the prose to the reader. Sometimes, in the theater, an actor must hold back tears so that the audience can have a catharsis. I think that is true in writing prose as well. You can’t weep all over the semi-colons yourself if you want the reader to access emotion; you must hold a little bit back. Cut, cut, cut, until the spirit shines through. I suppose that is a kind of craft.

_______________________________________

Smile: The Story of a Face by Sarah Ruhl is available now from Simon & Schuster.

Beth Henley

Elizabeth Becker Henley is an American playwright, screenwriter, and actress. Her play Crimes of the Heart won the 1981 Pulitzer Prize for Drama, the 1981 New York Drama Critics' Circle Award for Best American Play, and a nomination for a Tony Award.