A History of Violence: Walking the Blood-Soaked Shores of Spirit Lake

Rethinking an Early-American Captivity Narrative

Illustration by Joe Gough.

Imagine returning home, after an absence of months, hungry and cold, only to find that someone else has moved in and eaten all your food. And wants to shoot you. This is how the Spirit Lake massacre was more or less described to me, although I also heard, “It would be like finding someone else in your summer home,” an image intended to emphasize the Wahpekute Dakota’s tradition of seasonal migration. It’s a strange and portent word choice, considering the number of summer homes that now populate the region the terrorized Dakota used to call home, but when Abbie Gardner and her family—a unit of nine that included her parents and three siblings as well as a brother-in-law and two infant nephews—arrived via wagon to the Spirit Lake region in 1856, they saw, to their eyes, an uninhabited paradise. In her memoir, Abbie praised the far-stretching prairie, with its “mantle of green, and a thousand flowering plants.” She called the resin weed that dots it a “golden star.” Closer to the lakes, fowl rose from the grasses “in flocks which no man could number,” and in the lakes themselves swam “finny inhabitants;” schools of pike, perch, pickerel, bass that had “long gamboled below their transparent surface without fear of the white man.” Never before had “the numerous beauties of these lovely lakes greeted the eye of a white man.”

Thin, exhausted, and overjoyed at the bounty that they understood to be from God, the Gardners and the other members of their wagon train, about 40 people in all, decided to stay. Each family picked a cove to nestle into and call their own. The settlers tried to plow the tallgrass prairie, blue-green stalks taller than some men, for the first time in its existence on earth. Blades broke, blisters popped and bled. They needed more time, but there was none. It was late summer of 1856 and the time to plant crops had long passed. So, they did what they could, and they waited. With the burr oak that grew thickest at the edge of the lake, the Gardner family built a single room cabin for the nine of them to share; prairie hay, dried and topped with a bright red rug, covered the cabin floor. They waited for the snow to come, and it did; ghastly, beautiful, blank. The game that had seemed so plentiful in the warmer weather earlier went scarce. Starving, in a cabin packed in with snow and full of each other’s breath, they waited for it to melt, and it began, eventually, to do that too.

On March 8, 1857, the sun was out when what was left of the Wahpekute Dakota, led by Inkpaduta, returned to this land, the land they had been living on further back than memory could attest, land that Inkpaduta had refused to sign away even after a drunk white whiskey trader killed his children, killed his nephews, killed his wife and put his brother’s head on a pike, unintentionally making him chief. Inkpaduta, 60, an old man with the knowledge of decades and the power of a new ruler and a heart that was broken—he, they, what was left of the Wahpekute Dakota, returned to the land they loved, only to find that in their time away, someone else had built upon it walls and a door.

*

This past summer, I went to that door. It’s sunken in the dirt now, just like the Gardner gravestones a few yards to the north. From the cabin, I could hear jet-skis.

I was trying to understand what the land was, and why so many people had died for it. The land in question was a beautiful spot, a few hundred yards on the curve of a clear, fresh lake nine miles south of the Minnesota-Iowa border. Thick-muscled whitetails run through it, even now, surrounded as it is by tiny gray-faced houses that look always dressed for Halloween. Though no descendants from either side still live there, burr oaks—tiny saplings, perhaps, at the time of the conflict—stand and wave their arms in the air like people, and the Gardner cabin has been restored to almost its original form. Abbie herself oversaw much of that restoration, filling it in 1892 with items that reminded her of what life had been like, there with her family, in 1857. A scythe, a bucket, a low-slung corn husk bed. As a child, nestled against her brother and sister, Abbie had slept in one just like it. Authenticity drew a better crowd, and by her final return to the cabin, Abbie had learned to capitalize on her trauma. Inkpaduta never came back at all.

I was trying to understand what the land was, and why so many people had died for it.

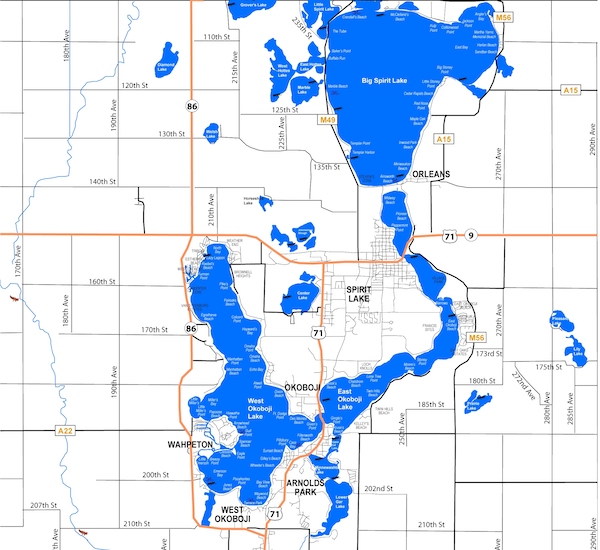

The names of the places involved here get confusing, so it’s best we clear some of that up now. From late June to mid-July 2016, I lived at Lakeside Lab, a 100-year-old ecological field station in northern Iowa. The names change approximately every 30 feet: Lakeside, Milford, Lakeview, Wahpeton, Triboji, West Okoboji, Arnolds Park, East Okoboji, Pillsbury Point. The whole watery spread is known as the Spirit Lake region, which is why the conflict is called the Spirit Lake Massacre, even though only two of the people who died actually lived on Spirit Lake proper. Most lived in the area locally referred to these days as Okoboji, as in West Okoboji Lake, the one that hangs like a locket from the others when you look at a regional map. You see it everywhere, the crest for a college that doesn’t exist: stickered to the back of cars, printed on cheery postcards for purchase at the pier gift shop. Many wear tee- and sweatshirts with UNIVERSITY OF OKOBOJI stamped across the front, although, if you ask, none know that in Okoboji, in the late winter of 1857, 38 people died on a plot of stolen land about a 10-minute walk from Captain Jack’s margarita bar. They come for the weather, the wild; they come because their parents did. They love the outdoors. Shirtless and red-faced, the men and the women fish, landing crappie, large-mouth, pike. They throw their slippery bounty into a cooler cradled on the floor of their boat and as you kayak pass, they call out to you, friendly, and stretch out their arm, and as your hand closes around the Coors they offer, your fingertips and theirs brush.

Okoboji probably translates to reeds. Inkpaduta’s name translates to “Red Cap,” “Red End,” or “Scarlet Point.” Historians can determine that meaning with a little more confidence, or so Mike Koppert told me. Mike is a 69-year-old local historian and lifelong resident of Arnolds Park, where he was elected to city council five times and where he spent 25 years of his life as the manager of the Gardner cabin’s one-room museum, until 2012, when state funding evaporated and he was let go. Mike is a rich source of strange yet verifiable information. For example, when we met in December to catch up and talk more about the conflict, he told me that last month he nearly bled to death on his toilet from diverticulosis. As is Mike’s conversational trademark, the details were frank and enthusiastically forthcoming, but I, who was driving and am bad with blood, felt my wrists go weak on the wheel and my eyelids sank until I changed the subject to the fictionalized biography on Inkpaduta he’s been working on for the last two years. Mike described the birth scene he was working on—a stream, Inkpaduta’s mother laboring, a baby’s tiny cry—and how it was tradition that members of Inkpaduta’s tribe be given a baby name, changed upon young adulthood to something reflective of a quality the member seemed to possess.

Okoboji is an area, an anglicized word with indigenous roots; Inkpaduta is a man, an indigenous name with colonial cause. His name is Red End because that is what happened to his face. I had never seen smallpox scars; I google-image searched them later and regretted it. When his brother was killed, Inkpaduta attempted to go through white channels of justice: the US Army ignored his petition, and the only prosecutor around took Inkpaduta’s brother’s head from the whiskey trader and nailed it to a pole over his house. Mike told me about this and other atrocities, involving long-dead generals whose names are now gifted to rivers, and children of all colors who starved that winter on ground too frozen to crack open and hold their bodies. Extremely generous and with an uncanny recall for detailed fact, Mike later sent me back to Iowa City with an original watercolor of a landscape and a woman sunk together. Her hair, the rich soil of prairie in early spring; her eyes are birds.

*

One morning at Lakeside last summer, I woke up early and rode my bike four miles to Cayler Prairie. The roads were damp and dirt and mud thickened my jeans; although it was cool out, I began to sweat under the sun. In a state where less than one percent of the pre-colonial vegetation remains, Cayler is 160 acres of uninterrupted, tallgrass beauty, but it is a beauty that lives enormous, between four- to six-and-a-half feet in height, and the spruce-colored blades are strong and sharp. Upon arrival, I leaned my bike on a fence and began, following a place where the grass seems most matted down—a DNR path, maybe, or a deer run, and quickly began to grunt and push. The prairie is open to visitors, but to keep it as pure as possible, there are no real trails. I imagined wagon wheels breaking, the horrible twist of an ox’s fetlock. Mud filled my shoes. Prairie is wetter than you think, and full of flowers, which means it’s also full of butterflies and birds. Everywhere I looked, things glittered and flew. I texted a friend. I’m in virgin prairie! I wrote. Unlike me, it’s never been plowed!

The concept of virgin land, of purity and its worth, is a weird one. It confesses to a kind of before and after that has never really existed. After the Dakota men entered the Gardner cabin, Abbie’s father instructed her mother to feed them, as well as the women and children who lingered outside. She made pancakes. They ate. The band disappeared. A couple hours later, gunshots were heard from across the lake. According to Abbie, her father grabbed his gun and instructed his family to brace for death, even as he swore to take the Dakota down with them. Her mother convinced him to wait, to try and appease the men with more flour and straw.

When he returned, Inkpaduta was restless. He paced the cabin’s small and wintered space. Abbie’s father turned his back to him, she writes, to get more food; at that, one of the Dakota men pulled a trigger. Her father was dead where he stood; her mother, who had lunged for the gun, was bludgeoned with the butt of it, and death began.

For ransom, for protection, Abbie Gardner was not killed, although, she writes, she begged to be. As a 13-year-old, Abbie Gardner spent 81 days in captivity, traveling with Inkpaduta and the others across the prairie, across the Little Sioux River, west and west. She was shoved but fed. Dakota women greased and braided her hair, but also mocked her. She learned their language and pinched their babies. Eventually, Abbie was rescued in Minnesota by representatives of the federal government, a strange bunch comprised of both white and Yankton men, the last hoping that their service to the white government would help protect their own tribe. But first, there was a cost.

For ransom, for protection, Abbie Gardner was not killed, although, she writes, she begged to be.

For their role in Abbie’s release, the Yankton men were paid $400 each, and they did not let Abbie out of their sight until the money was in their hands. In all, over $3,000 was expended by the territory of Minnesota to secure Abbie’s freedom. “The price paid for my ransom was 2 horses, 12 blankets, 2 kegs of powder, 20 pounds of tobacco, 32 yards of blue squaw cloth, 37-and-a-half yards of calico and ribbon, and other small articles,” she writes. Upon her ransom and return, she lived with relatives of another murdered settler, and ended up marrying one of them very quickly. She was still 13.

“She probably was considered ruined goods by the people of the time,” one professor at Lakeside told me. When I asked another, gingerly, about the possibility of sexual assault, he frowned deeply. “Perhaps,” he told me, “but rape in connection with conquest was more of a European tradition.” It’s a quote I can’t forget, and it makes me feel deeply uncomfortable in ways I am still working through. Mike backed it up. At the time, he told me, many tribes in the region thought white people were filthy, lower than animals. It may well have been beneath a Dakota man to touch her. Nevertheless, fear of her rape was used, as Abbie documents in her memoir, to rally state and territory troops. Letter after letter included in her book comes from a general or a colonel or a lieutenant referring to her as a “white woman” in danger of “indignities;” referring to her as “our.” As is so often in colonization and warfare, rape here is weaponized, but in a different way: it’s the threat of, not the act itself, that is militarized. Government officials spent $3,000 to get her, but what they gained in return went beyond her living body; a righteous, Christian reason to invade; a type of proof for the necessity of their literally staking the land.

*

Every classic, early-American captivity narrative follows the same arc, and Abbie Gardner’s memoir, History of the Spirit Lake Massacre and Captivity of Miss Abbie Gardner is no exception. The opening bell is one of apology from the woman writer for daring to write in the first place. She begs forgiveness for her rude display of authority and skill. She promises that she tried to find someone else to write her story, someone with more talent, more right. She promises that she didn’t want to do this, but the people in her life compelled (frequently, the word “forced” is used), her to write her account, for the education of the country and for the honor of God, who did protect her in her time with the Devil. For us, she suffers again, and in that suffering, regains her status as pure.

“In doing so I hope to benefit myself, [and] pay a lasting tribute to the memory of those whose lives were consecrated,” Gardner writes, “to civilization.”

What my friend said about summer homes and finding someone in there, Goldilocks style, except this Goldilocks was armed, was meant to illuminate the desperate plight of Inkpaduta and his fellow family. But it could also describe Abbie. Eighteen months after the Dakota men pushed open her door, and stepped inside, the now 14-year-old Abbie returned to the cabin with her new husband and found it occupied by a pastor named J.S. Prescott, whom she ultimately could not shame into giving her back her home. The laws of the United States, so willing to overlook Dakota rights to the same land in favor of her white father, now in turn ignored Abbie’s. As an orphaned, barely-teenager, she could be married. As a woman, no matter how white, she could not legally access her father’s federal land claim.

The laws of the United States, so willing to overlook Dakota rights to the same land in favor of her white father, now in turn ignored Abbie’s.

And so, Abbie moved, but did not move on. In 1891 she came back from New York, a quietly-divorced mother of two, and bought back the cabin where she saw eight of her family members shot and then beaten to death with firewood. She collected indigenous curios; she wrote a memoir. From the cabin’s door, she sold both. The site of the state’s last massacre became the state’s first tourist attraction. So many visitors, flush with capital from the Industrial Revolution’s second act and able to purchase leisure for the first time in their lives, came to the cabin to hear Abbie’s rendition of events and take her tour of the land that in 1921 the town built a roller coaster a ten-minute walk to its east. It still stands, and is still made of bone-clattering wood; this summer, I rode it and screamed my head off.

In the century that’s passed since the coaster’s first climb, other tourist draws have appeared. A Ferris wheel, a critically-regarded summer theatre, a palm-reading booth. A drive-thru church, America’s oldest; a strip club named Zippers that shares a lot with an antiques mall. And of course, there is the land itself, wild and enveloping and rich, in game and icy glacial waters and steaming prairie and a sky that looks touchable. “Summer homes, but for people who ride Harleys,” says a friend about the region when I tell him I’ve been, as well as “the Jersey Shore of Iowa,” but this being Iowa, even the Jersey Shore of Iowa doesn’t really seem that trashy.

*

Sometime during my second week in Okoboji I started calling it the conflict instead of the massacre. It came up during a conversation with Jane, a brilliant local with snapping eyes who runs outreach for the nonprofit arm at Lakeside and wears macaroni necklaces although she has no children. It came up with Mike, as we cruised around the curl of Marble Bay, so named for the white couple living there until Inkpaduta and others raided and killed them. It came up with a descendant of Abbie Gardner-Sharp and his two grandkids over the lunch we had at a Mexican restaurant that also specialized in spaghetti dinners. We had met at the Gardner cabin, where they were learning about their family roots, and I was lurking. As we dug into tacos he insisted on paying for, I asked Darrell, Abbie’s great-grandnephew many times removed, what this story is about.

A devout Christian with a sweet, crinkly face, Darrell sees this as a story of redemption and forgiveness: he pointed to Abbie’s collections and tour-guide work of the cabin as evidence that she wanted the people of Okoboji to understand the people who had kidnapped her, rather than condemn them. It was important for Darrell to take his grandchildren, who sat, bored and polite, on either side of him, to the cabin. It’s their history. He calls it a massacre because, he said, that’s what it was. He calls it a story of forgiveness because, he said, Abbie forgave Inkpaduta. When I asked Darrell if Abbie, or the white settlers of the region at large, had anything that they, in turn, needed forgiveness from Inkpaduta for, he nodded gently, and then said no.

*

At the Gardner cabin one day during my last week in Okoboji, I pressed my face to glass, peering in, as Mike bent down and pulled something out of the ground under the cabin’s window. Catnip. Later, he would take his bounty back to Maricita, the black cat who sits in the window and luxuriates in the fine warm air of habitual marijuana use that identifies Mike’s apartment. Two months ago, my phone lit up with snapshots of paintings Mike had done of his leg while recuperating from necrotizing fasciitis at the VA hospital in Sioux City, where he was also busted for pot use, twice in one day. “On federal ground, too!” he told me with glee. Before his diagnosis, Mike was hitching for a ride up to Standing Rock, where he hoped to join other US veterans pledging to form human shields around Sioux water protectors. The paintings of his disintegrating leg are disturbing, beautiful.

In her later years, Abbie Gardner painted too. Today, three of her paintings hang on the walls of the museum from which her memoir is still sold. The details are vivid, the paint carefully applied. In one, a drowning white woman is hit with sticks when she flounders too close to shore. In another, a circle of Dakota men smoke a pipe while, in front of a teepee at the painting’s edge, a blonde girl sits, huddled in blankets, and watches. In the third, the light of a cabin’s flames reveal a small gray dog with its tail between its legs. They are large, these paintings, three feet by two in one case, and in her fifties and sixties Gardner worked on them nightly and alone.

Gardner survived with, and then off of, her memories and her loss. She had to, and she could.

“Oh, she definitely had PTSD, they just didn’t call it that back then,” Mike told me. Gardner survived with, and then off, her memories and her loss. She had to, and she could. There was a market for it. Nineteenth-century American literature is famous for its romanticism—of the exterior landscape of the frontier, and the interior landscape of the self—but a midcentury move toward realism focused on straight-forward depictions of the habits and behaviors of everyday, ordinary Americans. With their close-up look at the home lives of the racialized Other and a strong tendency to spiritualize, or otherwise personify, the natural habitat around them, captivity narratives caught something of both trends, and thus became something else: a form of memoir that paid female writers, financing their self-sufficiency as long as they remained bound to their trauma; a useful tool of propaganda in the colonization of North America; and a compelling narrative formula based in the real suffering and mythical purity of white women. This formula could be called upon to justify white violence and attacks. History of the Spirit Lake Massacre and Captivity of Miss Abbie Gardner was first published in 1885, during the last, desperate years of indigenous and federal wars. It became a patriotic bestseller.

Onto one of her paintings, Gardner added the words “READ YOUR HISTORY.” They are a command, centered; a commercial, captioned. It does not get less complicated if we acknowledge her words are also a heartfelt, tormented plea. In its later editions, this painting made its way into her book. Inkpaduta left no painting, no written record, and conversations about him with possible Dakota descendants of his are as of yet closed to me, an outsider—another white, female writer. Reports from the late 19th century, written by a furious US military, place Inkpaduta in Minnesota, then the Dakota territories, then in Montana, where he met a Lakota named Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotȟake, known otherwise as Sitting Bull. Together, they led and fought in the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876; together, during the ensuing retribution that followed the battle’s initial success, they led what remained of their family and followers to Canada. Later, Sitting Bull came back to the US, but Inkpaduta would remain in this new land, with his beloved people, until his death in 1881.

The only photo that purports to be him, hung up and framed in the Gardner cabin museum, is probably of his sister.

Katie Prout

Katie Prout received her BA from Kalamazoo College and her MFA from the University of Iowa’s Nonfiction Writing Program. Her writing has appeared in Longreads, Lit Hub, and other publications, and in 2017, her micro chapbook Liner Notes was published with Ghost City Press. She is currently at work on a book about her family’s history with addiction, football, and ghosts.