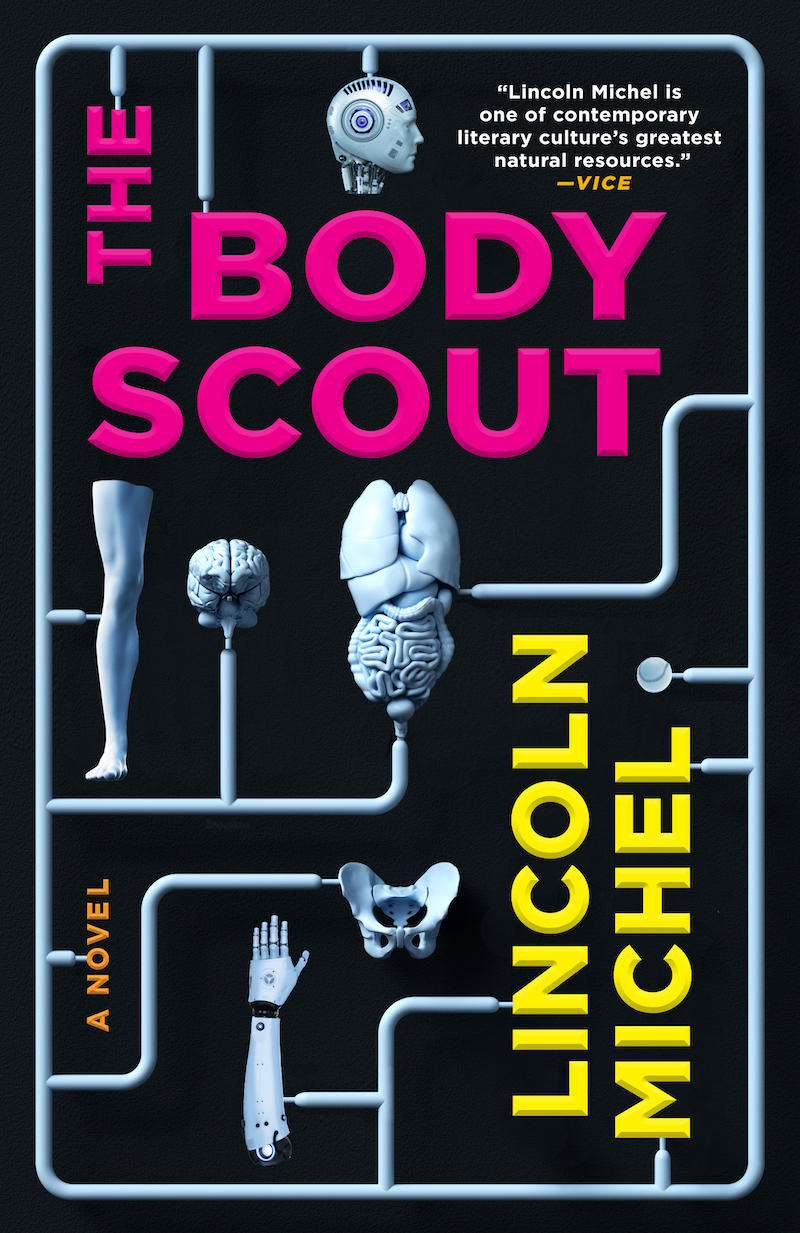

COVER REVEAL: Lincoln Michel’s The Body Scout

Plus, Read an Excerpt From This Near-Future Dystopian Neo-Noir

The following is from Lincoln Michel’s forthcoming novel, The Body Scout, about “a hardboiled baseball scout hunting down his brother’s killer in an all-too-possible future ravaged by climate change and repeat pandemics, where back-alley body modification, genetically edited CEOs, and cybernetic loan sharks abound and the human body is just another product.” Available from Orbit this coming October.

Scroll down for a first look at the cover, designed by Lauren Panepinto.

*

Chapter One

The Dark Hours

When I couldn’t fall asleep, I counted the parts of the body. I used the outdated numbers. What they’d taught me back in school when only the ultrarich upgraded. Two hundred and six bones. Seventy-eight organs. The separate parts floated through the fog of my mind, one by one, like strange birds. If I was still awake by the end, I’d think about everything connecting. Miles of nerves and veins snaking through the pile, tying tibia to fibula, connecting heart to lung. Muscles, blood, hair, and skin. Everything joining together into a person, into me.

Then I swapped in new parts. A second cybernetic arm or a fresh lung lining for the smog. Cutting-edge implants. This season’s latest organs. I mixed and matched, tweaked and twisted.

I didn’t know if I was really getting myself to sleep. I might have been keeping myself swimming in that liminal ooze between waking problems and troubled dreams. It was a state that reminded me of the anesthetic haze of the surgery table. Like my mattress was a slick metal slab and the passing headlights were the eyelamps of surgery drones. Outside, the world went by. Construction cranes hoisted buildings tall enough to stab the clouds. Cars cluttered the skies. But inside, my senses dulled, the world was gone. I was alone and waiting to wake up as something different, better, and new.

I’d been piecing myself together for years. With surgeries and grafts, with shots and pills. I kept lists of possible procedures. Files of future upgrades that would lead me to an updated life. My brother, J.J. Zunz, always laughed about it. “One day I’m going to wake up, and none of you will be left,” he’d say. That would have been fine with me.

We’re all born with one body, and there’s no possibility of a refund. No way to test drive a different form. So how could anyone not be willing to pay an arm and a leg for a better arm and a better leg?

Sure, we’re each greater than the sum of our parts. But surely greater parts couldn’t hurt.

Each time I upgraded it was wonderful, for a time. I had new sensations, new possibilities. I was getting closer to what I thought I was supposed to be. Then each time seemed to require another time. Another surgery and another loan to pay for it. Two decades of improvements and I still wanted more, but now I had six figures in medical debt crushing me like a beetle under a brick.

That night, as I was Frankensteining a new body for myself in my head, my brother called. The sound jostled me. My imaginary form collapsed, the parts scattering across the dim emptiness of my mind. I opened my eyes. Yawned. Slapped the receiver.

A massive Zunz appeared before me, legs sunk through the carpet to the knees, face severed at the ceiling. He was so large he could have swallowed my head as easily as a hardboiled egg.

“Kang,” he said. He paused, then repeated the name with a question mark. “Jung Kang?”

I shrunk his hologram to a proper size. He glowed at the end of my bed. For some reason, he was wearing his batting helmet. It was three a.m.

“Um, no. It’s me, Z. Kobo. You dial the wrong address?”

Outside, the bright lights of the city illuminated the nighttime smog. A billboard floated past my window, flashing a Growth Cola ad. The Climate Has Changed, Your Body Can Too.

“Yes. Kobo.” He shook his head. “My brother. How are you?” Zunz spoke haltingly, like he either had a lot on his mind or nothing at all. He looked healthy at least. A lot of players in the league wanted the retro bodybuilder style, muscles stacked like bricks, but Zunz made sure the trainers kept him lean and taut. When he swung a baseball bat, his arms snapped like gigantic rubber bands.

“Shit, Z. You sound like you got beaned in the head with a bowling ball. What do the Mets have you on?”

“Lots of things,” he said, looking around at something or someone I couldn’t see. He had several wires connected from his limbs to something off feed. “Always lots of things.”

Zunz was a star slugger for the Monsanto Mets and my adopted brother. After the apartment cave-in killed my parents and mushed my right arm, his family took me in. Gave me a home. Technically, I was a few days older than him, but I never stopped thinking of him as my big brother.

“Kobo, I feel weird. Like my body isn’t mine. Like they put me in the wrong one.”

“They? You gotta sleep it off. Hydrate. Inject some vitamins.” I unplugged my bionic right arm, got out of bed. Tried to stretch myself awake. “Here, show me your form.”

Zunz didn’t have a bat on him, but he clicked into a batting stance.

“Fastball right down the line.”

He swung his empty hands. Stared into the imaginary stands.

“Fourth floor. Home run,” I said. Although his movement was off. The swing sloppy and the follow through cut short.

Zunz flashed me his lopsided smile. Got back into his stance. “Serve me another.”

When Zunz first got called up to the big leagues, he used to phone me before every game to get my notes. I never had much to say. Zunz had always been a natural. But I was a scout, and it was my job to evaluate players. Zunz needed my reassurance. Or maybe he just liked making me feel needed. As his career took off, he started calling me less and less. Once a series. Once a month. Once a season. These days, we barely talked. Still, I watched every game and cheered.

“Sinker,” I said. My bionic arm creaked as I threw the pretend pitch.

I watched his holographic form swing at the empty air. It was strange how many ways I’d seen Zunz over the years. In person and in holograms, on screens and posters and blimps. I knew every curve of his bones, every freckle on his face. And I knew his body. It’s shape and power. At the Monsanto Mets compound, he had all the best trainers and serums on the house. I’d never get molded like that, not on my income. But watching Zunz play made me want to construct the best version of myself that I could.

“You look good to me. ChicagoBio White Mice won’t know what hit him.”

Zunz pumped his fist. Smiled wide. He may have been in his thirties, but he still grinned like a kid getting an extra scoop of ice cream. Except now he frowned and shook his head. “I feel stiff. Plastic. Unused. Do you know what I mean?”

“Well shit, Z.” I held up my cybernetic arm. “I’m practically half plastic already. But you look like a million bucks. Which is probably the cost of the drugs they’ve got pumping through you.”

I lit an eraser cigarette and sucked in the anesthetic smoke. After a few puffs, I felt as good and numb as I did before an operation.

Thanks to Zunz, the Mets had built a commanding lead in the Homeland League East and cruised through the division series against the California Human Potential Growth Corp Dodgers. As long as they could get past the ChicagoBio White Mice, the Mets were favored to win the whole thing.

“Give the White Mice hell, Zunz,” I said, blowing out a dark cloud. “Show them a kid from the burrows can take the Mets all the way.”

“Will do, Kang,” Zunz said.

“Kobo,” I said.

“Kobo.” He cocked his head. I heard muffled yelling on his end of the line. I couldn’t see what was around him. Zunz’s hologram turned. He started to speak to the invisible figure.

He shrank to a white dot the size of an eyeball. The dot blinked. Disappeared.

The call had cut out.

I finished my eraser cigarette and went back to sleep. Didn’t think about the call too much. The biopharms were always pumping players with new combinations of drugs in preparation for the playoffs. Hoping to get the chemical edge that would hand their team the title, which would lead to more retail sales that could purchase more scientists to concoct new upgrades and keep the whole operation going. Zunz was a high-priced investment. Monsanto would keep him together.

And I had my own problems to worry about. Sunny Day Healthcare Loans was threatening to send collection agents after me again, and I had to skip town for a few days. I took the bullet train down to North Virginia, the latest break-off state, to scout a kid whose fastball was so accurate he could smack a mosquito out of the air. It was true. He showed me the blood splat on the ball.

The Yankees authorized an offer. The number on the contract made the parents’ eyes pop like flyballs. But when I gave the kid a full work-up, I realized they’d been juicing him with smuggled farm supplements. The kind they pump into headless cattle to get the limbs to swell. The kid’s elbow would blow out in a year. Maybe two.

The parents cried a lot. Denied. Begged for a second opinion. I gave them the same one a second time.

I was one of the few biopharm scouts left who specialized in players. Other scouts plugged the numbers into evaluation software and parroted the projections, but I’d spent my whole life desiring the parts of those around me. People like Zunz, who seemed to have success written into their genetic code. I watched them. Studied them. Imagined myself inside them, wearing their skin like a costume, while I sprinted after the ball or slid into third.

I still liked to think baseball was a game of technique and talent, not chemistry and cash. I guess I was a romantic. Now it was the minds that fetched the real money. That’s what most FLB scouts focused on. Scientists working on the latest designer drugs. Genetic surgeons with cutting edge molecular scalpels. For biopharm teams, players were the blocks of marble. The drugs sculped them into stars.

By the time I got back to New York, the playoffs were in full swing. I got a rush assignment from the Yankees with a new target. I’d planned to go to the game, watch Zunz and Mets play the White Mice from the front row with a beer in my hand a basket of beef reeds in my lap. But the Yankees job was quick work and easy money. Which meant I could quickly use that money on another upgrade.

The prospect was a young nervous system expert named Julia Arocha. Currently under contract at Columbia University. She was working on some kind of stabilization treatment for zootech critters. Her charts were meaningless scribbles to me, but I was impressed with the surveillance footage. Arocha was a true natural. She glided around centrifuges as easily as an ice skater, holding vials and pipettes as if they were extensions of her limbs.

They next night, I grabbed a cab uptown to the pickup spot. The playoffs were on in the backseat.

“What the hell?” the driver shouted as a Pyramid Pharmaceuticals Sphinxes fielding error gave the BodyMore Orioles a runner on third. The man flung his arms wide. They shook like he was getting ready to give someone the world’s angriest hug. “You believe that shit?”

“Bad bounce,” I offered.

“Bad bounce? My ass. Hoffmann is a bum. We’d be better off with some Edenist who’d never been upgraded playing right field instead of that loser. Don’t you think?”

“If you say so. I’m a Mets fan.”

He scowled. “Mets,” he said, gagging on the word.

The taxi flew over the East River. Great gray barges cut blue paths through the filter algae below.

“Mets,” he said again. “Well, the customer is always right. Zunz is a good one, I have to admit. They don’t make many players like that anymore.”

“They’re trying. You see the homer he smacked on Friday?”

“Right off the Dove Hospital sign. The arms on that guy. Wish we had him on the Sphinxes.”

“He’s going to take us all the way,” I said.

We flew toward the giant towers of Manhattan with their countless squares of light pushing back the dark, both of us thinking about J.J. Zunz. Imagining my brother’s hands gripping the bat, his legs rounding bases in our minds. His body perfect, solid, and, at that point, still alive.

Lincoln Michel

Lincoln Michel’s most recent novel is Metallic Realms (Atria Books). His previous books include the story collection Upright Beasts (Coffee House Press) and the novel The Body Scout (Orbit), which was named one of the fifty best science fiction of all time by Esquire. His fiction appears in The Paris Review, Strange Horizons, F&SF, Granta, and McSweeney’s. You can find him online at lincolnmichel.com and his newsletter Counter Craft.