Courage, Wilderness, Self, and Other: A Reading List of Exploration

Lindy Elkins-Tanton on the Books That Inspired Her Journeys

When I was a kid I read every story of exploration that I could find. I read about explorers trying to reach the north pole, and explorers trying to reach the south pole, and I read about explorers in ships in the violent ocean, but most of all I read about explorers discovering unknown animal species. These stories felt like magic to me: The courageous man goes to a new country, meets many amazing people, travels into the deepest forest or highest mountain, and captures alive the strangest creatures. He puts his hand into the dark hole at the bottom of the tree and lifts out the biting squirrel, lifts it gently, fearlessly.

Someday I will do that, I thought. I will travel with a small group of people. We’ll be adventurers, we’ll be free, and we’ll work in service of a higher calling, increasing humanity’s knowledge.

Then I went to college, and took courses in women’s studies, and experienced geological field work myself. And I realized that women were not invited to any of those historic expeditions, let alone to lead them; that many expeditions were for nationalistic or commercial purposes, not for discovery or science; that many expeditions represented the worst aspects of colonialism. I worried about the fear and abuse the captured animals endured, and I mourned over all those shot and carried back as skins and feathers. I thought, where is the discovery and the science? And where are the women (Gertrude Bell, Freya Stark, and…)? Is there any room for me in the world of exploration?

I began to question the notion of a hero, if by its definition most people were excluded from candidacy. Some of these people were heroes in the best sense, using their courage and achievement in support of their team and for the greater human good. Others, though, were cruel to their teams, or, perhaps like Charles Wilkes of the U.S. Exploring Expedition, placed their own fame or reputation above the importance of safety or ethics. (Some of today’s public “heroes” could use some of this medicine, to remember that fame for oneself is not an adequate goal in life.)

Now, thirty years later, having organized and participated in four field expeditions to Siberia, and am leading a robotic space mission to a metal-rich asteroid, I appreciate with much more poignancy the challenges of attaining new knowledge through exploration without sacrificing ethics or the best interests of those on the team. The harder the struggle, the greater the risk of loss, but the greater the potential reward (but see Apsley Cherry-Garrard’s story, below).

There’s something to test yourself against, something to emulate, and something to reject in each of these stories. Look into these books to see practices we need to improve upon and not relive, and then also, for deep inspiration and the sense of escape I yearned for when I read them first. In this world of climate change and political upheaval, immerse yourself in a less-spoiled nature, and immerse yourself in the tight horizons of a physical outdoor adventure: the deep joys of living in the immediate moment and location, of the smells, feelings, and sights of wilderness and the unfamiliar.

*

Carveth Wells, Six Years in the Malay Jungle

(Doubleday, Page & Company)

Its cloth cover peeling and curling, my father’s original copy of this book still sits in my bookshelf. Wells was sent to the Malay Peninsula to survey for a railroad, and was stranded there by World War I. The racism of the time is here, as would be expected, and also, detailed descriptions of the people, the flora, and fauna, a snapshot of a lost age. In this book, as a young girl, I first read about durian fruit. Decades later, when I ate my first one, I felt the connection to both my own childhood and to the Malaysia of 1913.

Ivan T. Sanderson, Animal Treasure

(The Viking Press)

The beauty of the animal illustrations alone in this book make it a prize. Sanderson traveled to then-British West Africa in the 1930s to collect little-known animals for the British Museum. His energetic, personal prose left an indelible imprint on me of what is needed to be an explorer. Here, he writes about his nocturnal pursuit of a bizarre small primate called a potto: “Holding the torch in my mouth I went after him… The small potto disappeared among the foliage. I found myself unable to descend because the tree below, which connected with the branch that I was on, had no side shoots at all and I was not well over a hundred feet above the ground.” Feel free to disregard Sanderson’s later preoccupations with UFOs and sea monsters, and take in the intense engagement with the natural world.

Apsley Cherry-Garrard, The Worst Journey in the World

(Dover Publications)

British Explorer Robert Falcon Scott died returning from the South Pole on this 1910-1913 Antarctic expedition, but Cherry-Garrard describes here a separate endeavor by another part of this same expedition team. He and two others travelled through the Antarctic winter darkness to find a penguin rookery and collect their eggs, unstudied by science and thought to be a key to understanding avian evolution. For me the beginning of this book dragged but the subsequent story of their efforts to travel to and from the rookery exceeds in degree of misery anything I have ever read, and indeed merit being called the worst journey in the world. Cherry-Garrard’s description is the very model of British uncomplaining understatement (we learn partway through, for example, that he is almost blind without his glasses, and they were uselessly iced over for most of his expedition). And the end of the book, when he finally delivers the hard-won penguin eggs, almost surpasses believing. Surely this is the ultimate expedition story.

Daniel L. Everett, Don’t Sleep, There are Snakes

(Vintage)

Everett receives the title of this book as advice from the Pirahã, a small tribe living in the Brazilian Amazon. He lives with them for years, at first attempting to convert them to Christianity while he simultaneously learns their language (imagine learning a language when there is no common language between you, and nothing to study). The language becomes a vehicle for transformation as he learns, Noam Chomsky-style, that its structure reflects the way the tribe thinks about the world, and that way is entirely different from, and ultimately in some ways more compelling, than the outlook Everett has at the beginning. Reading about his journey with the people and his struggle with the meaning and use of language changed how I think about speaking, thinking, and writing. This is a book best listened to in audio form, to hear the author pronounce the Pirahã’s language himself.

Scott Wallace, The Unconquered: In Search of the Amazon’s Last Uncontacted Tribes

(Broadway Books)

Yes, there are still remote peoples in the Amazon who fight to avoid contact with the outside world. In this book, Wallace introduced me to Sydney Possuelo, one of the world’s greatest explorers and a tireless fighter for the rights of indigenous people. Together they tread that fine line between learning enough about a group called the flecheiros (People of the Arrow) to be able to help protect them, without contacting them too completely or leaving them more vulnerable to other outsiders. As William Gibson said, “The future is already here—it’s just not evenly distributed.”

Evelyn Fox Keller, A Feeling for the Organism

(Times Books)

At MIT as an undergraduate in the mid-1980s I took classes from Fox Keller, and she gave me the context to understand and the language to discuss what it was to be a woman in science. In this biography of Barbara McClintock, who won the Nobel Prize in 1983, the year before publication, Fox Keller reveals the emotional connection McClintock had to her work, an aspect often neglected or even hidden when discussing scientists. Suddenly I saw a scientist as a whole person instead of as a cipher or a textbook, and for the first time had a model for what I might become myself. In this way her book is the best and purest kind of exploration, one that traces not only the path followed by the protagonist, but the path the reader might use to walk into the future.

Next on my reading list:

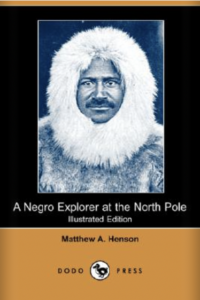

Matthew Henson, A Negro Explorer at the North Pole

(Dodo Press)

First published in 1912, this memoir is by Matthew Henson, who went aboard a Chesapeake Bay merchant ship at the age of 12 and went on to join multiple expeditions with Admiral Robert E. Peary, including Peary’s team that is thought to have first reached the North Pole. Henson learned Inuit. Henson was the first to reach the Pole. If I ever get to invite anyone in history to one of those imaginary dinners somehow made real, Henson is on my short list.

__________________________________

A Portrait of the Scientist as a Young Woman: A Memoir by Lindy Elkins-Tanton is available via William Morrow.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton

Lindy Elkins-Tanton is a world-renowned planetary scientist and member of the National Academy of Sciences. She is the Principal Investigator of NASA’s Psyche mission, and Vice President for the Interplanetary Initiative at Arizona State University, one of the top Earth and planetary science research schools in the United States. Among her major original research achievements are the discovery that the Siberian flood basalts caused the end-Permian extinction, the revelation that rocky planets are born wet, and the concept of “drip volcanism.” Asteroid (8252) Elkins-Tanton is named for her.