Contemplating Human Extinction, Deep in the Badlands

Digging for Dinosaur Bones Amid the Dakota Oil Boom

To get to Marmarth, North Dakota, skirt the edge of the Little Missouri grasslands, where wildfires and lightning can ignite veins of underground coal that smolder for decades, releasing smoke and fumes that warp the junipers into telltale columns. Head south to Bowman, where herds of bison graze, and follow the train tracks west out of town. The road drops into the Badlands just outside of Marmarth, where the green grass gives way to brown buttes and burnt outcrops and cell service dies. Once you cross the Little Missouri River, you know you’re there.

When I arrive at the bunkhouse—at the end of Main Street, next to the tracks and a railroad sign that says Marmarth, despite the fact that there is no depot and the trains don’t stop there anymore—it’s empty. In 1907, the president of the Chicago, Milwaukee, and St. Paul Railroad named the budding town after his granddaughter, Margaret Martha. To call Marmarth a ghost town is to do a disservice to the 125 good souls who live there, but the town has lost a lot since 1920, when its population stood at 1,318. Today, empty lots and abandoned buildings line the streets. Beside the Mystic Theater (built 1914) stand two old metal jail cells, one door swinging open. The Barber Auditorium, its pediment stamped 1918, remains boarded up. Painted on the entrance to the Cactus Club: Stay Out.

Marmarth has always been a place for hunters of some sort. Theodore Roosevelt shot his first grizzly to the west of here and his first buffalo to the north. He was searching for solace after losing both his wife and mother on Valentine’s Day 1884. The town experienced an oil boom in 1936, and my WPA guide mentions a nearby well pumping an unusual crude: ‘‘apparently high in gasoline and kerosene content, very light, but darker in color, and with a somewhat different odor.’’ Today—in the late summer of 2014—there are flares and pump jacks outside of town, but it’s not like up north in the massive Bakken oil fields—a.k.a. Kuwait on the Prairie—which have brought the state unprecedented wealth, growth, and problems. Five years ago, it was hard to get a room at the bunkhouse—Marmarth was crowded with roughnecks as older local wells were overhauled with new secondary and tertiary recovery techniques designed to increase the pressure and flow, but things have calmed down since. That is not to say the town has remained unchanged: its elementary school (pre-kindergarten through eighth grade divided between three classrooms) will open a $1 million addition this fall, funded in part with a no-interest loan from the county’s oil and gas royalties. Eighteen students are expected to start the new year. The nearest high school is twenty miles away in Montana.

On the afternoon I arrived, the single sign of life was a white oil-company truck parked in front of the town’s only bar, the Pastime Club & Steakhouse, where a bartender might ask a stranger, ‘‘Are you a bone picker?’’

I am part of a team digging up a juvenile Torosaurus, a relative of the better-known Triceratops. Officially, I am a volunteer member of the Marmarth Research Foundation, a scientific nonprofit dedicated to fossil education, excavation, and curation. Why are we here? For the state’s other boom. North Dakota in general—and Marmarth in particular—has found itself in the middle of a modern bone rush.

Henry Fairfield Osborn, president of the American Museum of Natural History and the man who named Tyrannosaurus rex, wrote in 1909: ‘‘The hunter of live game, thorough sportsman though he may be, is always bringing live animals nearer to death and extinction, whereas the fossil hunter is always seeking to bring extinct animals back to life.’’

‘‘Ready to go back in time?’’ the guy sitting beside me says, rather dramatically. He’s from Long Island and is also an amateur. We’re in a dusty Suburban pitching itself headfirst down a sharp slope into the Badlands. Through the cracked wind- shield, I see a moonscape eroded out of the prairie: a mottled topography of red, brown, black, yellow, green, and gray studded with naked buttes—the sediments of the sea, silt and clay deposited and then worn down, epochs later, by water and wind. In places, the buttes are scorched and collapsed by burning coal turned into ash. Nonnative sweet yellow clover has choked out the prairie grass that usually grows between the desolate washouts and draws; in parts, the clover stands waist-high. Above, sparse thickets of cottonwoods, maybe a green ash, a few ponderosa pines. Below, baked beaches where alien outcrops of rocks bloom in strangled, man-sized shapes. A landscape of hard eternity, home to rattlers, bull snakes, prairie dogs, pheasants, foxes, coyotes, pronghorns, bobcats, mule deer, minks, and ever-thirsty toads. My companions and I are dressed in paleontologist chic: tan pants, wide-brim hat, long-sleeve button-down, boots, bandanna. As our vehicle lumbers down the hill to the desolate floor, we pass a rock layer known as the Cretaceous/Tertiary (K/T) boundary, a thin line of tan clay beneath a band of coal that pinpoints the ‘‘sudden’’ geological moment when the dinosaurs disappeared.

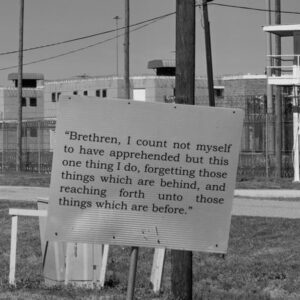

These aren’t the Badlands of South Dakota, which are thirty million years younger and far more popular. These are the Badlands that in 1864 Brigadier General Alfred Sully of the US Cavalry, busy marauding against the Sioux, described as ‘‘hell with the fires out.’’ Nearly one hundred years later, John Steinbeck wrote in Travels with Charley:

I was not prepared for the Bad Lands. They deserve this name. They are like the work of an evil child. Such a place the Fallen Angels might have built as a spite to Heaven, dry and sharp, desolate and dangerous, and for me filled with foreboding. A sense comes from it that it does not like or welcome humans.

The dig site has been worked for six weeks over three summers. I set my pack where someone previously found a dinosaur skull. There are no clouds and no shade. We’re digging through layers of sandstone and clay with chisels and hand picks, looking for signs of any remaining fossils: hard ‘‘rocks’’ with suspicious bony bands or marrow holes, or even just chunks of ironstone that might indicate we’re in the right area. Ting! Ting! Ting! go our hammers and chisels as we carve small benches into the face of the butte. Hitting bone sounds different—stop scraping then. The ground is littered with hard red-black mineral balls called concretions (damned fossil lookalikes!). We find nuggets of bright-orange amber, which one of us collects in a medicine bottle, hoping to turn them into jewelry. We dig into yellow spheres of soft, smelly sulfur. We hit a layer of ‘‘veggie matter’’ and turn up delicate specimens of leaves, mainly Dryophyllum. The rock usually cleaves along the plane of the leaf; on one side is an imprint, or image, and on the other is the leaf. (Look for the faint raised ridge of a stem.) We unearth thick mats of spongy organic matter, the veins of the plants perfectly articulated. I hit an ancient tree branch reaching through the rock; the wood is flecked with shiny dark cubes that smudge my fingers black. ‘‘What’s that?’’ I ask. Someone replies, ‘‘Charcoal, of course,’’ and I think of fossil fuels.

Of course North Dakota is most famous right now for another kind of excavation—the drilling of the Bakken oil fields. Currently, there are more than twelve thousand wells operating in North Dakota—a number that could quadruple in the coming decades. When I visited, more than 190 rigs were actively drilling new wells.

The Bakken Formation is a layer of 360-million-year-old rock that stretches some twenty-five thousand square miles across the US and Canada; it is the largest continuous oil accumulation assessed by the United States Geological Survey. About two-thirds of it lies below North Dakota, in the northwest corner of the state. Its discovery dates to the 1950s, but only very recently have rising oil prices and new technology—such as hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling—made extraction feasible. In 2006, North Dakota ranked ninth in domestic oil production. Now it’s number two, behind Texas. Republican Governor Jack Dalrymple has compared his state to a ‘‘small OPEC nation’’—and, indeed, it now pumps a million barrels a day, more than OPEC members Qatar and Ecuador. The month I’m in North Dakota, the news breaks: the United States has surpassed Saudi Arabia to become the top oil and gas producer in the world. The summer of oil!

We are excavating what is called the Hell Creek Formation: a bed of sandstone, siltstone, and mudstone deposited 65 to 67 million years ago by rivers flowing to the long inland sea that stretched north-south across what is now North America. The formation contains the last of the dinosaurs before they went extinct.

The Bakken is about 8,500 feet beneath the Hell Creek Formation—and some 300 million years older—but geologists say the oil was formed (cooked, as it were, out of the shale) at about the same time as the dinosaurs roamed and died. That is, both treasures being hunted and hauled out of the ground of North Dakota—the oil and the dinosaurs—are roughly the same age.

We carry our own water here; at least three liters a person. Water is precious, the subject of great conversation. What comes out of the tap in the bunkhouse gives out-of-towners the runs, so we pack big recycled plastic bottles filtered by reverse osmosis. In June, a pipeline spilled 2,000 barrels of fracking wastewater eight miles southwest of Marmarth, where the stream of pollution ran for about a mile before soaking into the earth.

Lunchtime: we sit in the holes we’ve just dug and throw our apple cores right off the hill. Eight hours of chiseling goes by surprisingly fast, despite the unrelenting sun and dust. At the end of the day, my back is wrenched and my hands are sore. Tyler, our leader, who is not with us today, found a Triceratops right over the next gumdrop butte. We spend 45 minutes searching but never find his excavation or the trace fossils leading up into the hill. We prospect around the base of the buttes for fallen bone fragments. We sift through the slopes of giant anthills, where the industrious diggers bring up fish scales, teeth, tiny pink vertebrae, and other fossils blocking their tunnels. We are ghouls with good intentions, looking for signs of death. Out here, everything crumbles, falls apart. The Badlands don’t preserve; they erode, which is why we find no modern bones, only age-old buried ones. The most recent corpse I come across is a desiccated bull snake. The silver sage smells wonderful when we brush against it, but the sudden whir of a grasshopper might make a nervous prospector jump, were he wary of rattlers. I take a picture of what I think is the K/T boundary on a high butte looming over us—between two gray rocks, an ominous band of coal, marking the lands below as belonging to the dinosaurs.

A dusty blue truck pulls up to the bunkhouse. A thick suntanned guy in his twenties walks in the door. He’s been here since April, when he came up from Arkansas. He was hoping to drive a truck—‘‘and not look like this at the end of the day’’—but they gave the job to someone with more experience. When we shake, his hands are black with grease and dirt. (A sign taped to the bunkhouse washer says ‘‘Absolutely no!!!!!!! greasers in the washer or dryer. –The Management.’’) The guy works maintenance for a company that lays concrete all over the state. He spent two weeks working on an intersection outside of Williston, in the heart of the Bakken oil fields, where he lived in one of the many temporary trailer cities known as ‘‘man camps.’’ ‘‘I fucking hate Williston,’’ he says. He’s now part of the crew building the new airport outside of Bowman. He’s in charge of his own repair truck; it’s better than working in Arkansas. ‘‘Now, if you’ll excuse me, I’m going to go get cleaned up,’’ he says. ‘‘I’ve got some drinking to do.’’

Nearly every morning at 4:00 a.m., the Burlington Northern Santa Fe rolls past the bunkhouse, just feet from our front door. I wake to the train—first the loud, breathy blast of the whistle, then the clacking and creaking of oil tank cars trundling by.

The Marmarth Research Foundation is the brainchild of paleontologist Tyler Lyson, a 31-year-old Marmarth native and Yale PhD who just finished a postdoctoral fellowship at the Smithsonian Natural History Museum in DC and will be taking the post of Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science this fall. The MRF digs on private land, mostly ranchland belonging to Tyler’s family. His father, Ranse, is a retired oil production foreman, and when I email Tyler out of the blue expressing my interest in oil and fossils, he invites me to dig, saying, ‘‘Sounds like an interesting idea: two very different ways that the past is enriching our state.’’ I’m onboard after signing an agreement not to reveal GPS coordinates or scientific information that might aid ‘‘fossil poachers.’’

Tyler is a dino-hunting prodigy. A restless, bearded live wire who often says ‘‘right?’’ (rhetorically) and can scamper up a butte like a mountain goat, he found his first fossil (the jaw of a duck-billed hadrosaur) at age six and got himself hired as a guide by a professor from Alabama when he was in the fifth grade. He has a particular expertise in turtles, and one of his finds includes a turtle ‘‘graveyard’’ that has yielded more than a hundred shells and three new species. This spring, Tyler was part of a team that announced the discovery of Anzu wyliei, a new 500-pound, 11-foot-long, feathered-but-flightless beaked dino-bird with a crested head and razor claws, something akin to crossing an emu with a reptile, and nicknamed in the press ‘‘the Chicken from Hell.’’

His biggest discovery, however, has been ‘‘Dakota,’’ the 67-million-year-old, four-ton Edmontosaurus he found on his uncle’s land in 1999 when he was only 16. Painstakingly unearthed over the next seven years, ‘‘Dakota’’ revealed itself to be a rare ‘‘dino-mummy’’—a fossil with nearly all of its bones, ligaments, tendons, skin, and scales preserved. The subject of a TV special and books for both adults and children, ‘‘Dakota’’ has traveled as far as Japan, though currently it is on display at the newly expanded North Dakota Heritage Center in Bismarck, which in a few months agrees to donate $3 million to the Marmarth Research Foundation for the right to permanently display the fossil—which might explain, in part, that confidentiality agreement.

We’re working a tight site. Tom, our field coordinator, says, ‘‘There just aren’t enough places to get at it.’’ It is the 400-pound Thescelosaurus jacket we’re about to flip over. A jacket is the excavated rock around a fossil that has been covered over with foil and then swaths of burlap soaked in plaster. A jacket might contain many bones—here, maybe 20 or so, Tom guesses. For support, we have built a wood frame and plastered it to the top. (‘‘We’re all getting plastered in the Badlands!’’ is a joke I’ve heard four times today.) Once we’ve carted the plaster block to the lab, someone will likely prep it—cut it open and painstakingly sift through it—over the winter, which is the equivalent of a rush job. Scientific priorities change over time, and one of the volunteers tells me that some museums have jackets they’re still only getting to from the 1800s.

We’re caught between the butte and some bones sticking up from the ground we don’t want to disturb. A film crew came by earlier and shot about three hours of us chiseling and plastering for a NOVA documentary. We waited for them to leave before trying to flip the giant jacket. We contort ourselves into odd positions—all hands on the jacket, feet placed with care—and heave together on a three-count. Once started, you have to keep the block moving—just watch your fingers and toes. A miracle: no earth falls out from the unplastered bottom. We carefully shave a foot or so off the top of the jacket, which then weighs a more manageable 150 pounds. We plaster a thin topcoat, and the next morning we gingerly set the jacket on a burlap stretcher hung between thick poles—like some great beast caught on safari—and then carry it up the hill and onto the truck. We drive back to the lab on a red clinker road built by an oil company that had no luck with its well.

On a Monday night at the Pastime—where a painting of a pump jack hangs above the pool table, the jukebox plays Waylon Jennings alongside Katy Perry, and a sign behind the bar advertises all-you-can-eat crab every Friday from five to nine—the bartender might charge out-of-towners anywhere from 50 cents to a dollar more for a bottle of beer, bringing the total to an even three bucks. A few locals bend over their drinks. The bar can be rough, but not tonight. I’ve already heard of one legendary fight at the Pastime: a troublemaker brought up the topic of ‘‘liberalism’’ and ‘‘open-minded thinking’’ and the resultant brawl spilled out into the street and down the block into the bunkhouse, which, since that night, has had a lock on its door.

At a high-topped table sits a very tattooed French palynologist, Antoine, who studies ancient pollen and spores and whose samples will help date the Hell Creek layers. The NOVA film crew (a British director, a cameraman, a boom guy) has ordered a pizza from Baker, Montana, which will arrive in an hour. When the director of the Smithsonian Natural History Museum walks in the door and buys me a beer, he tells me he has been coming to town for the past 34 years. ‘‘You could dig here forever,’’ he says. ‘‘It’s raining dinosaurs.’’

The MRF lab has enough jackets stored away to last for years. They rest on huge wooden pallets in the warehouse and line the metal shelves against the walls. Others are secreted away in locations around town. A field coordinator named Stephen picks a rock from an open jacket and points to a nearly invisible line less than a millimeter thick winding its way through the stone. ‘‘Look—fossilized skin from a Thescelosaurus.’’ I nod and pretend I see what he sees. The man knows skin; he’s one of the ones who prepped ‘‘Dakota.’’ This piece was collected at least a decade ago, before Stephen came onboard. The jacket we just hauled out of the Badlands sits on a wooden table. There’s a chance Stephen will be taking it home with him to Michigan at some point.

The collection room is a crypt of wonders that diminishes the casual visitor: such impossibly large bones—what giants left them behind? Femurs out of The Flintstones, a Triceratops horn longer than my arm. I ponder a number of turtles huddled in situ in stone, like some half-buried suicide pact. Barb, ten years at MRF and my guide for the tour, points toward the back: ‘‘In these cabinets is arguably the world’s best collection of turtles.’’ She’s right and she’s wrong: sure, there are drawers and drawers of shells, heads, and tails—not to mention a fully articulated turtle foot that’s so beautiful I almost want to cry. (Most turtle species cross the K/T boundary—that is, they didn’t die out in the global event that doomed the dinosaurs.) But the cabinets contain countless other finds: fearsome claws from bird-beasts, delicate reedlike tendons, sly and sinister dinosaur beaks, a massive tail that was smashed in battle and then healed, the vertebrae fused.

When I leave the lab that night, another preparator also named Stephen is bent over a magnifying glass, picking away at a massive Triceratops vertebra with a miniature pneumatic jackhammer called an air scribe. He’s been working on this bone for three years. He says, ‘‘It’s beautiful, isn’t it? These parts here’’—he holds up the swooping sides—‘‘rise up like wings.’’ In the next room, Barb is running the air abrader, her hands in a big glove box—like a scientist fighting an infectious disease—as she blasts a giant bone with baking soda. The fossil looks beautiful, as if settled in snow. Giant air compressors whir as she picks away the past, one grain at a time.

On my way out, I stop by the tabletop sandbox, which is filled with red garnet sand and used as a soft space to puzzle out how fossils fit together. Two big pieces of a hadrosaur tibia stand upright, as if growing out of the sand, while next to them someone has carefully laid out a handful of turtle fragments. There is something unexpectedly touching about the 20-odd chips of shell arrayed in an incomplete oval, the central mound of red sand ready—ever hopeful—to cradle the bones.

Later, I will ask Tyler, ‘‘Why turtles?’’ He tells me they have a rich fossil record— they’re as common as leaves. He’s captivated by the evolution of their bodies, how they lock their ribs into a shell (‘‘It’s one of those features that appears exactly once in earth’s rich history, like the bird feather’’). But what stays with me is this: ‘‘You find dinosaurs here and there, but turtles are pretty continuous through time.’’

A cartoon on the lab’s bulletin board shows the ‘‘Causes of Mass Extinctions.’’ The Cretaceous period is ended by a meteor, the Pleistocene by a change in climate, and the Age of Man by an ‘‘act of stupidity’’: a caveman bangs a hammer against a bomb that seems to be resting on oil drums. On the bomb is written: ‘‘God is on our side.’’

‘‘Ebola: What You Need to Know’’; ‘‘Gaza Crisis Brings 9/11 Flashbacks’’; ‘‘Surgeon General Calls for Action to Reduce Skin Cancer Rate’’; ‘‘Suicide Bomber from U.S. Returned Home Before the Attack’’; ‘‘Race to Find India Landslide Missing’’; ‘‘NATO ‘Unprepared for Russian Threat’’’; ‘‘Six Dead in Nigeria College Blast’’; ‘‘Drug-Resistant Malaria Widespread’’; ‘‘Why Do Americans Not Buy Diesels?’’; ‘‘Midwestern Waters Are Full of Bee-Killing Pesticides’’; ‘‘White House: Ignoring Climate Change Will Cost America Billions’’; ‘‘U.S. Oil Exports Ready to Sail’’; ‘‘Should America Keep Its Aging Nuclear Missiles?’’; and ‘‘Winds of War, Again’’ are some of the headlines I read late one night while in Marmarth.

In some ways, this moment feels particular, transitory, just a sliver in time. Though it seems unlikely (if not impossible) to me, many interested parties believe impregnable oil pipelines can be built, wastewater will be recycled, gas flaring curbed, the earth protected, and safe and spacious cities will arise on the western plains of North Dakota. But something about the crises of this summer in the Bakkan—the violence, the spills, the fires, the crashes, the explosions, the drugs, the crimes, the crowding—feels endless, eternal. The question is not so much How did this happen? but Why do we always find ourselves here?

And then, while I’m in Marmarth, the opposite thought occurs. This is it. We’ve reached the brink, we had our chance; our turn is over.

On a dig, one might talk about Victorian pianos, brewing beer, maple syrup, Cretaceous vegetation, or modern sand channels, but most often the work is done in silence—save for the tink of hammers and chisels and the incessant scraping of awls and knives. The mind veers from the micro to the macro; if you’re not careful, you might get whiplash. You’re chiseling away with a short knife at a few inches of tough, barren cliff all morning when out pops a piece of amber, and suddenly you remember you’ve got your nose pressed up against a window looking 67 million years into the past. According to the female volunteers—some of whom prep fossils for this country’s major museums—dino-digging remains something of a boys’ club. But if paleontology might be conducted with a certain macho swagger, hunting for fossils is fundamentally humbling: again and again, you end up feeling so small. Where do I stand on this colossal, shifting earth? As alien as this landscape seems to me today, what sends my mind spinning is to think of it then—flat, warm, and wet, lush with ferns and vegetation. A humid coastal plain. Pretty much the opposite of the Badlands around me.

And these bones! Not only do they dwarf us, but these creatures lived so long ago. How do we measure ourselves—and our species—in geological time? A half blink, at best. Once again—why are we here? What could we ever contribute to science, that incomplete story we tell about ourselves? Paleontologists dwell in uncertainty and failure; they’re always saying, ‘‘We just don’t know’’ and ‘‘In 50 years, we might understand a little more.’’ These few feet of excavation, a couple of centimeters of carefully prepped bone. To dig is to be constantly confronted with your own pitiful insignificance.

We move to a possible hadrosaur site just below a ridge with a 360-degree view of the Badlands. Is there a duck-billed herbivore buried in this cliff—or enough of it, anyway, to make our work worthwhile? Within two minutes of brushing soft dirt, I find a reddish-orange rock. I put it on my tongue, and when it sticks, I know: I’m French-kissing a fossil! (The porousness of the bone clings to the surface of the tongue like an old, hard sponge. The sound the rock makes as you pull it away—like softly peeling an orange—is a deep, visceral thrill.) Most likely the piece eroded and tumbled down from a larger chunk of bone, and so with a scalpel and brush, I chase the dinosaur into the hill. But in the end it eludes me. We find only broken bits of tendon or perhaps a small rib. I put my piece on a short pile of bone, and we pack our gear and climb back up to the truck.

After a week of digging in the field, I find myself walking through town, unconsciously scanning the side of the road for fossils, studying the bigger rocks and imagining just where I would put my chisel to break open their secrets. At night, the Milky Way careens brilliantly overhead, looking like a band of stubborn sediment in the sky.

On my last day, we go prospecting in an area no one has searched in a decade. We agree to meet at a distant butte around lunchtime. On the ground we find hunks of frill—the wide bony plates that flared out the back of ceratopsian heads—plus scattered sections of vertebrae. I pick up a nugget. ‘‘Chunkasaurus,’’ says Antoine, the French palynologist. ‘‘A big, exploded dinosaur.’’ Later, I will see a naked rib sticking right out of a hill. I will pick up a square of crocodile scute, or fossilized armor, plus a shard of turtle shell and two small, broken dinosaur bones. One of us will find a stone Indian knife, a long right-handed blade that fits perfectly in your palm with grooves for your fingers. Someone else comes across a coprolite—a fossilized piece of shit. We will walk some eight miles in 100-degree heat, marking the GPS coordinates of anything worthwhile.

Not long after splitting up, I climb to the top of a tall butte, where I run into Antoine again. Antoine lives in Paris. He carries a shovel to dig trenches from which he takes careful samples—he then dissolves the rock layers in acid and studies the organic remnants under a microscope. The ancient spores and pollen help date and describe the environment. At breakfast this morning someone called Antoine ‘‘an extinction guy,’’ meaning he studies the K/T boundary, when the dinosaurs died off.

Today he has been searching for the boundary layer, but, alas, no luck. He scrapes at the cliff, frowns, and says, ‘‘The story here is complicated.’’ He just came across a rattler in its hole, so we double back around the butte. We scan the horizon, but there is no sign of our group. They’re crawling somewhere in the craters below us. We hunker down in a sliver of shade to eat lunch by ourselves, and I ask Antoine about his work. He tells me a lot of scientists study the late Cretaceous right up until the extinction. It’s popular: there are dinosaurs, drama, and death. But he’s curious how life clawed its way back from the devastation. He takes a bite of his sandwich and tells me, ‘‘I think that is where the interesting story lies.’’

The K/T extinction event—now more properly known as the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K/Pg) event, though the more recent name hasn’t really stuck—wiped out all non-avian dinosaurs and ended the Mesozoic Era. When I was growing up, what killed the dinosaurs was a subject of great debate. I remember picture books filled with hypotheses (volcanoes, continental shifts, natural selection, and so on). Science has since solved that mystery in spectacular fashion.

Some 66 million years ago, a six-mile-wide asteroid—speeding in low from the southeast around 45,000 miles per hour—crashed into the Gulf of Mexico right off the town of Chicxulub on the Yucatán Peninsula, sending up unimaginable amounts of flaming dust and debris that scorched the surface of the earth before darkening the skies and bringing about an ‘‘impact winter’’—in essence, causing a change in atmospheric composition that led to a change in climate that led to trouble for those on Earth. Firestorms. Earthquakes. Megatsunamis. Shifts in ocean chemistry. Mass extinctions as years of darkness and cold gave way—as the particles settled out of the atmosphere, many falling as acid rain—to centuries of intense global warming (from the CO2 blasted into the air). The event is at once spectacular and familiar. Three-quarters of the species on Earth eventually died in the fallout.

You can change a climate from without, say via flaming asteroid, or you can change it from within, say via the steady combustion of fossil fuels. If getting oil out of the ground is hard on the earth, burning it is worse. That is, one way to consider the Bakken is as a site of local hemorrhaging, the symptom and symbol of a greater, far more devastating disease. Since the Industrial Revolution, humans have pumped 365 billion metric tons of carbon into the air by burning oil, coal, and gas. Atmospheric CO2 is up 40 percent, and we are on track to double the preindustrial level in the next 35 years. (Meanwhile, concentrations of methane have already doubled.) As we know, greenhouse gasses warm the planet. By 2050, temperatures might rise as much as seven degrees. As Elizabeth Kolbert writes in her book The Sixth Extinction, ‘‘This will, in turn, trigger a variety of world-altering events, including the disappearance of most remaining glaciers, the inundation of low-lying islands and coastal cities, and the melting of the Arctic ice cap.’’ She also points out that the oceans absorb a fair amount of this CO2, which makes them more acidic, or poisonous to life.

Geologists employed by Pemex, a Mexican oil company, originally discovered the Chicxulub impact crater. Already an ever-growing fleet of ships is fracking the ocean. The wastewater is treated and—supposedly harmless—dumped into the sea. ‘‘Deep Water Fracking Next Frontier for Offshore Drilling’’ is a headline Reuters runs while I’m in North Dakota. According to the article, the ‘‘big play’’ is a formation called the Lower Tertiary in the Gulf of Mexico, which just happens to be the layer of rock on top of that earlier, more fateful big boom.

In a few months, I will cross the Gulf of Mexico, leaving from Texas and passing deepwater drilling platforms before sailing near, but not over, the Chicxulub crater. I will stare out at the ocean—dark blue to the horizon in every direction, the black depths below—and I will shudder to think that our clumsy actions have the power to raise the temperature, by even a single degree, of these endless waters that bathe us.

The K/T event was not the planet’s most cataclysmic upheaval. That distinction goes to the far older Permian-Triassic extinction, a period 252 million years ago also known as ‘‘the Great Dying,’’ when 90 percent of all species on the planet died out. It’s the only time the insects were killed too. The planet grew incredibly hot; sea temperatures might have risen as much as 18 degrees. The world nearly wiped itself clean. The exact feedback mechanism is still being debated—Siberian volcanism, global warming, ocean acidification, the melting of frozen methane, the production of hydrogen sulfide—but most scientists think the dying began with the release of greenhouse gasses.

The catastrophic volcanism that many believe triggered the Great Dying is thought to have released less carbon annually than we humans currently emit into the air.

Convert the heat our emissions add to our planet into something more visibly spectacular: imagine 400,000 of the atomic bombs that scorched Hiroshima detonating every single day.

Today, long-frozen methane in the Siberian permafrost is warming—and then exploding. Formerly trapped gas is also being released along the coast, where methane plumes bubble to the surface of the sea (in concentrations ten to fifty times greater than normal). Methane is a far more powerful greenhouse driver than carbon dioxide.

When I was in North Dakota, the internet was abuzz about a mysterious giant crater that suddenly appeared on Russia’s Yamal Peninsula. The crater, which was spotted from a helicopter by oil and gas workers, was thought to have been formed by the ejection of underground methane melted out of the permafrost. The past two summers on the peninsula had been unusually hot. More large craters will continue to be found. Yamal translates into ‘‘end of the world.’’

When I think of extinction, I picture something gradual. But that isn’t how it happened for the dinosaurs—and it’s not what’s going on today, speaking in geological time. The day before I left for North Dakota, a study titled ‘‘Defaunation in the Anthropocene’’ came out in the journal Science. The gist: we are in the midst of the earth’s sixth mass extinction. The culprits: do I even need to say? The study points out that since 1500, a total of 322 species of terrestrial vertebrates have become extinct. Those that have survived our ever-growing presence have declined 25 percent in population. Earlier that spring, a Duke study revealed that plants and animals were going extinct at a thousand times the rate they were before humans appeared. Some 20,000 species currently hang in the brink.

The pace seems to be quickening. A month after I returned from North Dakota, the London Zoological Society reported that over the past four decades, the world’s wildlife population had been cut in half. Rivers have emerged as a particular killing zone—freshwater animals are down 76 percent. Meanwhile, turtles—which handily survived the K/T event—have been reduced by 80 percent. In about the same span, the human population has doubled.

The larger animals aren’t repopulating; smaller animals are taking over, a pattern borne out by other extinction events. Today that means rodents, who help spread disease. Wheels within wheels. All I can think of is that we should have known it was coming—the meek shall inherit the earth.

Of course, the Bakken boom will slow—if not go bust, at least partly—as oil prices fall from the summer of 2014 to the beginning of 2016. During the downturn, Saudi Arabia keeps its production high—glutting the market—in what most consider to be an effort to cripple US fracking operations, which require a higher oil price to break even. In the Bakken, small operators get squeezed out; the number of active drilling rigs plummets. Oil-field fatalities rise, perhaps due to companies cutting corners. North Dakota no longer boasts the lowest unemployment rate. The governor calls for budget cuts; the state announces it will no longer offer free vaccines to children. Many newcomers leave, if they’re able. A developer tells Reuters, ‘‘It seems like people are on the fence, waiting.’’

Nevertheless, the US remains the top oil and natural-gas producer in the world, as drillers prove more flexible than imagined, cutting costs and pumping more oil to stay afloat. Production in the Bakken never falls below a million barrels a day. By mid-2016, the price of oil crawls back up to 50 dollars a barrel. An industry analyst tells the Wall Street Journal that that price should signal an industry-wide ‘‘all clear,’’ as companies weigh whether to complete more wells. On the campaign trail in Bismarck, Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump promises to slash environmental restrictions and unfetter the fossil-fuel industry. The candidate has called global warming ‘‘bullshit.’’

Meanwhile, climate scientists warn the tipping point is closer than we think. Energy production in the US is leaking far more methane than previously calculated—potentially offsetting recent reductions in carbon-dioxide emissions. The year 2014 is the hottest ever recorded, until 2015 breaks the mark by the largest margin yet. So far, 2016 seems a sure bet to be even hotter.

My last night in Marmarth and we’re racing to Mud Buttes to beat the dying of the light. A stretch of Badlands just out of town, Mud Buttes is one of the best places in the world to find the primary markers of the K/T boundary, to put your finger on the moment of impact. We speed down a gravel road as Tyler lists off the physical evidence, debris thrown from the crater that shows up in rock layers worldwide: iridium (a dense metal rare on Earth but common in asteroids), spherules (glassy beads of once-molten rock), and ‘‘shocked’’ quartz (the mineral’s crystalline planes deformed under great pressure—a phenomenon first noted after nuclear testing).

The sun sinks lower, turning a mushroom-shaped cloud on the horizon a stunning pink and lending our errand an even greater sense of apocalypse. But the mood in the truck is buoyant; some are drinking beer, excited to be nearing the end of something. A fingernail moon hangs in the darkening sky. Natural gas flares burn in the distance; others snarl in pits by the side of the road. We jump out of the car and scamper across the Badlands, heading for the butte. As he runs, Tyler calls back, ‘‘This ecosystem is 30,000 to 40,000 years before the rock falls.’’

Later, Tyler will say: ‘‘You want me to tell you about the survivors? After the rock hits, it sends out a thermal pulse, so at least a good chunk of North America gets fried as things come flying back in from space. Everything gets sent up into the atmosphere. Months up to maybe a year of varying degrees of darkness. The cold—that’s what I think largely kills the plants. And anything that relies primarily on plants is shit out of luck. Anything that’s big—over a meter, roughly—goes extinct. So that pretty much takes care of all dinosaurs. The largest land turtle. The largest alligator. The big things in the ocean.’’

Tyler squats before one of several trenches dug out of the butte. He points to a lighter stripe of red-tinged rock beneath a band of coal and says, ‘‘This is the actual boundary, right here.’’ Antoine talks us through the layers: the spherules, which landed first, because they were heavier; then the ‘‘shocked quartz,’’ followed by the iridium anomaly. I run my finger along the boundary, rich with cosmic dust and melted chunks of Mexico that rained down on North Dakota. A line not many fossils cross, those few centimeters marking the end of an era. Tyler reaches in. ‘‘Age of dinosaurs,’’ he says, then raises his finger a fraction: ‘‘Age of mammals.’’

‘‘If you have a slow metabolism, you’re better able to survive. If you’re small, you’re better able to survive. And if you’re living in the water, or burrowing, you’re better able to survive—things like crocodiles, some lizards, and turtles. A lot of the big animals get taken out. But then they are rapidly replaced. It opens up all these niches. And mammals very, very quickly take over.’’

Some of us walk to the edge of the butte to watch the sun set. But Antoine’s not finished. He moves his hand up the rock face. Annihilation: the planet’s been scrubbed free of animals—not many fossils here. Then comes a sharp increase in fossilized fern spores—known as the ‘‘fern spike’’—as these plants were among the first to recolonize the seared landscape. Higher up, he wrestles a chunk out of the butte. At last, a sign. ‘‘Look. Do you see what those are?’’ I do not. Brown coils wind through the black-flecked rock like thick strands of spaghetti. After a pause, he tells me: ‘‘Worm burrows.’’

My mind tunnels inward. I think of family and friends back home, lives left in the rearview. I think of rigs going up and men breaking down: in bars, in parking lots, in temporary trailers. I think of those who know the land and those who just rent it. I think of fires, water, and the hard, cracked earth—and the part of us that longs to break it wide open. I think of what this looks like from space, or from the other end of eternity. I think of things buried, the bones left behind. I think of long sacrifices and short-term gains. And, finally, I think of my young daughter, her love of dinosaurs, how I haven’t spoken to her or my wife all week except over email and text, since I was beyond cell service, beyond a lot of things, really. How will I tell them what I saw in North Dakota?

The air grows cooler. A few lowing cattle climb the butte above. From somewhere unseen, a bird chirps twice, then stills—the song of a survivor, a distant dinosaur relative. Soon, we’ll be gone, but for now we linger on the edge as silence falls across the Badlands, and the sun sets on this world, and the last one, and the one that is to come.

‘‘Picking Bones in the Badlands’’ was excerpted from ‘‘Chasing the Boundary: Boom and Bust on the High Prairie,’’ forthcoming in the essay collection The History of the Future (Coffee House Press) in May 2017.

Edward McPherson

Edward McPherson is the author of Buster Keaton: Tempest in a Flat Hat, The Backwash Squeeze and Other Improbable Feats, and The History of the Future: American Essays. He has received a Guggenheim Fellowship and a Pushcart Prize, among other awards. He teaches creative writing at Washington University in St. Louis.